Sore Throat

Perspective

In 2007 the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey reported more than 2 million emergency department visits for sore throat and “throat-related” complaints.1 Thus sore throat remains among the most common presenting complaints in both emergency departments and outpatient care settings in the United States.1,2 Although some subtypes of pharyngitis and peripharyngeal disorders are more common in children and adolescents, individuals of all ages commonly develop sore throat.

Pathophysiology

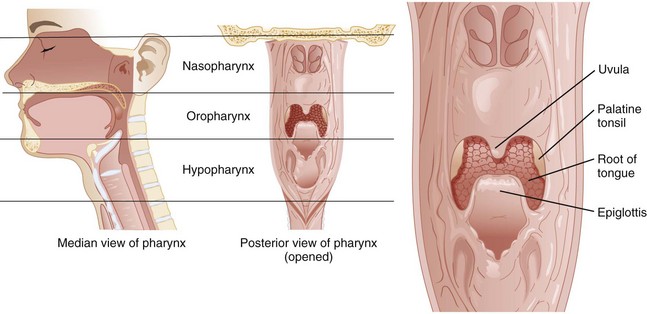

Sore throat, or pharyngitis, is generally caused by inflammation in the soft tissue of the pharynx. There are three anatomically distinct regions of the pharynx: the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and hypopharynx (Fig. 23-1). Pathology involving one site usually involves the others, but inflammation at any of these levels can manifest as a sore throat. The nasopharynx encompasses the area superior to the oral cavity, between the base of the skull and the soft palate. The eustachian tubes, connecting the middle ear and pharynx, open into this space. The oropharynx is the region directly visible on examination, lying behind the oral cavity, between the uvula and hyoid, including the vallecula and epiglottis. Laterally, it is defined by the tonsillar pillars. The hypopharynx is the most caudal aspect of the pharynx. It lies inferior to the epiglottis and terminates where the aerodigestive paths become distinct, at the esophagus and larynx; the vocal cords define the inferior pole. If one looks directly at a patient, this region is posterior and slightly superior to the thyroid cartilage. There are several important potential spaces surrounding the pharynx; disease in the retropharyngeal and submandibular spaces can manifest as not only pain but airway compromise.

Diagnostic Approach

Airway Assessment and General Appearance

The evaluation of sore throat begins with a simultaneous assessment of the airway and the patient’s general appearance. A history of rapidly progressive symptoms, difficulty breathing, or a sensation of tightness in the throat suggests potential threats to the airway. Examination begins with direct observation. Patients with airway compromise often sit upright or lean forward, with the neck extended and jaw thrust forward, and appear restless and distressed. Drooling may indicate an inability to swallow oral secretions and thus inflammation or pathology in the oropharynx or hypopharynx. Drooling is a sign of an advanced airway process, requiring prompt preparation for detailed evaluation and intervention. Presence of a muffled voice prompts consideration of a supraglottic threat to airway patency. The floor of the mouth should be visualized, and the submental region palpated as “brawny” induration or tenderness in this area is classically associated with Ludwig’s angina (Table 23-1). Stridor, a high-pitched noise heard on inspiration, indicates a process involving the glottic or infraglottic structures. Stridor indicates a true airway emergency, except when occurring in young children (<10 years old) with croup (see Chapter 168). Stridor is associated with ominous conditions such as epiglottitis, retropharyngeal abscess, and angioedema, and the severity and rate of onset and progression of symptoms indicates the urgency of the required intervention.

General appearance is assessed with attention to hydration status and markers of systemic toxicity. Patients, particularly children, with significant pain from uncomplicated pharyngitis often have difficulty with oral intake and may become dehydrated. Fever and mild tachycardia are common vital sign derangements in those with viral or bacterial pharyngitis and do not typically indicate dangerous pathology. A prolonged fever (greater than 5-7 days) in children may be associated with Kawasaki disease.3

Viral versus Bacterial Pharyngitis

In the context of acute uncomplicated pharyngitis, considerable attention has been focused on differentiating between bacterial and viral infection through either bedside testing or clinical scoring. Various scoring systems, the most famous of which is the Centor criteria system, incorporate components of the history and physical examination to generate an estimate of group A streptococcus (GAS) infection.4 The four Centor criteria are history of fever, tonsillar exudates, tender anterior cervical adenopathy, and absence of cough. In a large prospective study including both children and adults that evaluated a modified Centor score (if age was greater than 45 years, 1 point subtracted), the prevalence of GAS increased with the number of criteria present. The prevalence of GAS was 1% with a score of −1 to 0, 10% with a score of 1, 17% with a score of 2, 35% with a score of 3, and 51% when the score was 4 or more. The distinction between viral and bacterial disease is, however, largely academic. With increasing emphasis on symptomatic relief and decreasing emphasis on eradication of the infecting agent, treatment, prognosis, and follow-up are virtually identical regardless of microbiologic cause5 (see Chapter 72).

Special Considerations on History

Although most patients with a sore throat have an uncomplicated infectious pharyngitis, certain components of the history are suggestive of more unusual pathology. Patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are at risk for oral candidiasis or thrush. In addition, primary HIV infection can manifest with upper respiratory infection (URI)–like symptoms, including acute pharyngitis in up to 75% of cases.6 Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors predispose patients to angioedema, and although the lips and face are often visibly edematous, the process can be limited to the tongue, oropharynx, or hypopharynx. Nonimmunized children are at risk for epiglottitis and severe, life-threatening infections caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, and adults may have epiglottitis regardless of immunization status. Dental procedures, particularly involving the lower third molars, can be complicated by postoperative infections, the most potentially serious of which is Ludwig’s angina. Recent orogenital contact should broaden the differential diagnosis, as gonococcus and herpes simplex virus (HSV) can be pathogens in the pharynx. Pharyngitis in teenagers or young adults with significant cervical lymphadenopathy and fatigue suggests infectious mononucleosis caused by the Epstein-Barr virus. In one large case series of patients with head and neck cancers, hoarseness and sore throat were the two most common presenting complaints. In older patients, particularly men with a history of smoking, neoplastic causes should be considered.7

Ancillary Testing

Laboratory testing is of very limited use in the context of acute pharyngitis. Most professional societies in the United States, including the American College of Physicians, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the American Heart Association, and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend various diagnostic strategies to distinguish between GAS and non-GAS pharyngitis. These include the combination of a clinical scoring system that allows a reliable estimation of pretest probability with a rapid antigen-detection test or throat culture. Treatment of proven GAS pharyngitis with antibiotics confers only a modest reduction in the duration of symptoms, and most western nations have abandoned this approach because the inaccuracy and risks of testing and treatment for GAS seem to outweigh the benefits in industrialized settings where rheumatic fever tends to be exceedingly rare. In the United States, however, guidelines still recommend a combination of clinical assessment and bacteriologic testing, with the goal of treating with antibiotics when GAS is identified or strongly suspected (e.g., by scoring criteria). This is described in detail in Chapter 72. Heterophile antibody testing for mononucleosis may be considered in patients with an extended clinical course or treatment failure; however, confirmation of this disease is important only to exclude “treatable” causes of pharyngitis and to ensure appropriate advice regarding contagion, limitations of activity, and so on (see Chapters 72 and 130).8

Imaging

Although radiographic imaging has long been recommended for evaluation of the epiglottis and structures in the hypopharynx, direct visualization of the structures of interest by examination is preferable, providing definitive diagnosis, assessment of the extent of the threat to the airway, and the ability to either plan for or perform intubation. In adults with possible epiglottitis, particularly those with severe symptoms such as drooling, distress, or muffled voice, examination via nasopharyngoscopy at the bedside or via laryngoscopy in the operating room setting is the best approach. Examination of this sort, however, should occur under a “double setup,” with availability of and preparation for an emergent rescue airway, usually cricothyrotomy, because manipulation of the irritated upper airway tissues may precipitate laryngospasm and obstruction. Endoscopic examination also allows identification of other life-threatening causes beyond infection, such as foreign bodies, polyps, and angioedema. If there is concern for epiglottis but upper airway examination by endoscopy is not possible (e.g., equipment is not available) and the patient has a stable airway, plain film radiography can be used for screening purposes. Findings on plain film suggestive of epiglottitis include the “thumb sign” (widening of the epiglottis silhouette) and the “vallecula sign” (opacification of this space).9 The approach to pediatric airway infection, including epiglottis, is described in Chapter 168.

Ultrasound is an emerging technology with applications for the detection of hypopharyngeal conditions including epiglottitis. In a convenience sample of adults, the epiglottis was easily visualized and measured in both males and females.11 A recent case report documenting the use of ultrasound in a patient with epiglottitis suggests this noninvasive bedside tool could prove useful in the diagnostic approach to the disease.12

In a child or adult with signs and symptoms of a deep neck infection, such as retropharyngeal abscess, and whose airway security has been ensured, the most useful imaging modality is computed tomography of the neck. The lateral neck x-ray examination is a relatively sensitive test for this disease, so in lower-risk patients a normal film (no widening of the prevertebral space, normal lordotic curve of the spine, and absence of soft tissue air) can be a useful risk stratification tool.13 Ultimately, however, CT is the definitive evaluation for deep neck infection. It is highly accurate at detecting infection in the deep tissues, but its ability to differentiate between cellulitis and abscess is variable.14 In children with a sore throat and a visible inflammatory neck mass, ultrasound diagnosis can be definitive.15

Empirical Management

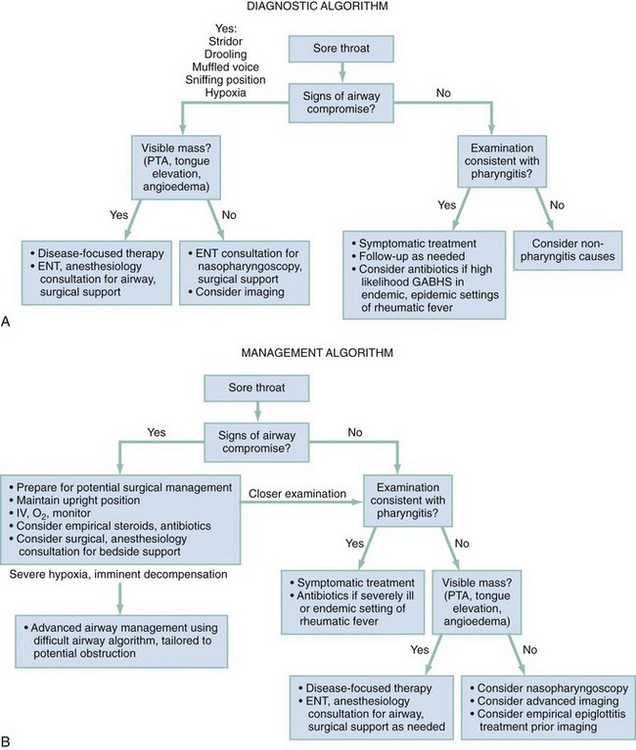

Figure 23-2 shows a clinical algorithm for the initial approach to, and management of, the sore throat presentation. Airway compromise and impending airway compromise, when present, must be addressed first. Infectious syndromes suggesting severe systemic illness or sepsis should be treated accordingly. Patients who clinically appear to have no potential for airway compromise and no signs of invasive or systemic disease can be managed according to presumptive causes.

Most commonly, sore throat will be caused by acute pharyngitis, in which case pain management with acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is the mainstay of care and the most important initial step in empirical management. Regimented administration of these agents, rather than use of as-needed approaches that fail to prevent or interrupt spiraling pain, is often helpful in maximizing their impact. In comparative studies of pharyngitis in patients with confirmed streptococcal infection, antibiotics have not been shown to be superior to NSAIDs for symptom reduction and therefore should not be used for this purpose.16 For moderate to severe pharyngitis, corticosteroid therapy reduces pain and duration of pain, with most studies using 0.6 mg/kg (maximum dose 10 mg) of dexamethasone, orally or parenterally, in a single dose.17 Opioid pain medication is appropriate in select cases of more severe pain, but the consideration of opioid analgesia may also indicate a more severe syndrome requiring additional evaluation. Proper pain management should be targeted to allow patients to reestablish nutritional balance, achieve and maintain a hydrated state, and ingest medications as necessary.

In the setting of clinical pharyngitis a fluctuant unilateral peritonsillar mass should be drained whenever possible. Drainage in such cases constitutes definitive care.18 Antibiotics often are used in cases of unilateral swelling and redness that appears not to be fluctuant (i.e., “peritonsillar cellulitis”); however, there are no data to support or refute this approach. For patients with manifestations of severe, systemic illness (i.e., those requiring hospitalization or those with impending airway compromise), antibiotic coverage for streptococcal and anaerobic bacteria may theoretically be helpful, and therefore we recommend antibiotic administration in this setting (see Chapter 72). However, no explicit evidence is available to support or refute this practice.

With the possible exception of gonococcal disease, two systematic reviews of the literature have concluded that acute pharyngitis should not typically be treated with antibiotics.5,19 The great majority of cases are viral in origin, and suppurative complications following streptococcal infection are both easily treated and too rare to justify routine use of antibiotics. In particular, antibiotics were beneficial in reducing rheumatic fever only during a single military epidemic in the mid-twentieth century, and the decline of rheumatic fever is unrelated to trends in antibiotic use, but rather is a result of factors associated with industrialization including improved living conditions, access to care, hygiene, and nutrition.20 This helps to explain the present day epidemiology of rheumatic fever, a disease that is extremely rare in developed nations but continues to be an important public health threat in developing regions throughout the world.21 Antibiotics should therefore be used to prevent rheumatic fever and other nonsuppurative complications only in endemic and epidemic settings.

It is important to note that adverse events caused by antibiotics are common and frequently result in emergency department visits,22 and the overuse of antibiotics for self-limiting conditions such as pharyngitis remains rampant.23 Thus for both public health reasons and the prevention of unnecessary harm to individual patients, antibiotics should be avoided in the management of this common, mostly self-limited condition.

References

1. Niska, R, Bhuiya, F, Xu, J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010;26:1–32.

2. Hsiao, CJ, Cherry, DK, Beatty, PC, Rechtsteiner, EA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 summary. Natl Health Stat Report. 2010;27:1–32.

3. Harnden, A, Takahashi, M, Burgner, D. Kawasaki disease. BMJ. 2009;338:b1514.

4. Centor, RM, Witherspoon, JM, Dalton, HP, Brody, CE, Link, K. The diagnosis of strep throat in adults in the emergency room. Med Decis Making. 1981;1:239–246.

5. Kenealy, T, Sore throat. Clin Evid (Online) Jan 13, 2011. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21477389.

6. Apoola, A, Ahmad, S, Radcliffe, K. Primary HIV infection. Int J STD AIDS. 2002;13:71–78.

7. Alho, OP, Teppo, H, Mäntyselkä, P, Kantola, S. Head and neck cancer in primary care: Presenting symptoms and the effect of delayed diagnosis of cancer cases. CMAJ. 2006;174:779–784.

8. Luzuriaga, K, Sullivan, JL. Infectious mononucleosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1993–2000.

9. Grover, C. Images in clinical medicine: “Thumb sign” of epiglottitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:447.

10. Reference deleted in proofs.

11. Werner, SL, Jones, RA, Emerman, CL. Sonographic assessment of the epiglottis. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1358–1360.

12. Hung, TY, et al. Bedside ultrasonography as a safe and effective tool to diagnose acute epiglottitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:359.

13. Nagy, M, Backstrom, J. Comparison of the sensitivity of lateral neck radiographs and computed tomography scanning in pediatric deep-neck infections. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:775–779.

14. Vural, C, Gungor, A, Comerci, S. Accuracy of computerized tomography in deep neck infections in the pediatric population. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24:143–148.

15. Rozovsky, K, Hiller, N, Koplewitz, BZ, Simanovsky, N. Does CT have an additional diagnostic value over ultrasound in the evaluation of acute inflammatory neck masses in children? Eur Radiol. 2010;20:484–490.

16. Thomas, M, Del Mar, C, Glasziou, P. How effective are treatments other than antibiotics for acute sore throat? Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:817–820.

17. Wing, A, et al. Effectiveness of corticosteroid treatment in acute pharyngitis: A systematic review of the literature. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:476–483.

18. Johnson, RF, Stewart, MG. The contemporary approach to diagnosis and management of peritonsillar abscess. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;13:157–160.

19. Del Mar, CB, Glasziou, PP, Spinks, AB. Antibiotics for sore throat. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2006.

20. Olivier, C. Rheumatic fever—is it still a problem? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;45:13–21.

21. Tibazarwa, KB, Volmink, JA, Mayosi, BM. Incidence of acute rheumatic fever in the world: A systematic review of population-based studies. Heart. 2008;94:1534–1540.

22. Budnitz, DS, et al. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events. JAMA. 2006;296:1858–1866.

23. Grijalva, CG, Nuorti, JP, Griffin, MR. Antibiotic prescription rates for acute respiratory tract infections in U.S. ambulatory settings. JAMA. 2009;302:758–766.