Chapter 37 Soft Tissue Sarcomas

Introduction

Soft tissue sarcomas are rare mesenchymal tumors that originate from the mesoderm, with the notable exceptions of those arising from primitive neuroectodermal tissue and those with unknown cell derivation, such as Ewing’s sarcoma or synovial sarcoma.1,2 Because more than 50 clinically and molecularly distinct sarcoma subtypes exist, there is tremendous clinical variation that leads to marked heterogeneity in their respective clinical behavior, prognosis, metastatic risk, and chemotherapy responsiveness.3 For this reason, although many soft tissue sarcomas are treated similarly, clinicians must be aware of the subtype-dependent nuances. Despite having nearly the same incidence as multiple myeloma or thyroid carcinoma, soft tissue sarcomas are responsible for more deaths than testicular tumors, Hodgkin’s disease, and thyroid cancer combined.4,5 They are two to three times more common than primary malignant bone tumors, and despite apparently complete surgical resection, they often metastasize to the lungs.

Epidemiology and Etiologic Considerations

Soft tissue sarcomas account for approximately 1% of all primary adult malignancies and 7% to 15% of pediatric neoplasms.2,6 The general incidence of these tumors is 1.4 per 100,000, but it rises to 8 per 100,000 in people older than 80 years. Roughly 40% of all soft tissue sarcomas occur in people older than 50 years.2 The American Cancer Society estimates a combined incidence of soft tissue sarcomas (including heart) in adults and children of about 10,980 new cases (6050 males and 4930 females) and about 3920 deaths (2060 males and 1860 females) for the year 2011.7 The overall incidence has been gradually increasing, in part due to better diagnosis but also probably due to a true increase in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)–associated Kaposi’s sarcoma.8 A male-to-female ratio of approximately 1.2 to 1 has been reported, although this varies considerably depending upon the sarcoma subtype.2 The relative frequency of each subtype of soft tissue sarcoma varies according to age. For instance, rhabdomyosarcoma mostly occurs in children, synovial sarcoma in young adults, and malignant fibrohistiocytoma (MFH) in older populations. Benign soft tissue tumors are approximately 100 times more common than malignant soft tissue tumors. Soft tissue sarcomas are most often seen in the extremities (59%), trunk (19%), retroperitoneum (15%), and head and neck (9%).2

The vast majority of soft tissue malignancies occur sporadically without any predisposing cause. However, soft tissue sarcomas may occur 3 to 15 years after irradiation for lymphoma, cervical cancer, breast cancer, or testicular cancer.9 Viruses have also been implicated with some soft tissue sarcomas, such as leiomyosarcoma, and with Kaposi’s sarcoma in patients with AIDS.10 Chronic lymphedema-associated angiosarcoma (Stewart-Treves syndrome) occurs as a rare complication of breast cancer treatment.11 An increased incidence of soft tissue sarcomas has been reported in several genetic disorders, such as neurofibromatosis, hereditary retinoblastoma, and Li-Fraumeni syndrome.12 Chemicals, such as Agent Orange (a dioxin-containing herbicide) and immunosuppressive drugs, are an uncommon cause of soft tissue sarcoma.13

Key Points Epidemiology and risk factors

• Soft tissue sarcomas can be seen at any age; most occur after age 50 years.

• They make up approximately 1% of all primary tumors in adults and 7% to 15% in children.

• They most commonly occur in the lower extremities.

• Most soft tissue sarcomas occur without any predisposing cause. In a few instances, genetic, infections (viral), chemicals (Agent Orange), physical agents (radiation), and immunosuppressive drugs may be contributory.

Histopathologic Considerations

The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies more than 50 histologic subtypes of soft tissue sarcomas as shown in Table 37-1.3 Thus, histopathologic diagnosis of soft tissue sarcoma is essential before treatment. In general, biopsy should be performed on any symptomatic or enlarging soft tissue mass that persists for longer than 4 weeks or is larger than 5 cm in diameter.5

Table 37-1 Modified World Health Organization Classification of Soft Tissue Sarcomas

| TUMOR TYPE | TUMOR |

|---|---|

| Adipocytic | |

| Intermediate (locally aggressive) | Atypical lipoma (well-differentiated liposarcoma) |

| Malignant | Liposarcoma: dedifferentiated, myxoid, round cell, pleomorphic, mixed type, not otherwise specified |

| Fibroblastic/Myofibroblastic | |

| Intermediate | |

| Locally aggressive | Superficial fibromatosis, desmoid-type fibromatoses, lipofibromatosis |

| Rarely metastasizing | Solitary fibrous tumor and hemangiopericytoma, infantile fibrosarcoma |

| Malignant | Adult fibrosarcoma, myxofibrosarcoma |

| So-called Fibrohistiocytic | |

| Intermediate (rarely metastasizing) | GCT of soft tissues |

| Malignant | Pleomorphic fibrous histiocytoma or undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (MFH), giant cell fibrous histiocytoma or undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma with giant cells, inflammatory fibrous histiocytoma or undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma with prominent inflammation |

| Smooth Muscle | |

| Malignant | Leiomyosarcoma |

| Pericystic (Perivascular) | Malignant glomus tumors, malignant hemangiopericytoma |

| Skeletal Muscle | |

| Malignant | Rhabdomyosarcoma: embryonal, alveolar, pleomorphic, botyroid, spindle cell, and rhabdomyosarcoma with ganglionic dedifferentiation |

| Vascular | |

| Intermediate | |

| Locally aggressive | Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma |

| Rarely metastasizing | Retiform hemangioendothelioma, Kaposi’s sarcoma |

| Malignant | Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, angiosarcoma of soft tissue |

| Chondro-osseous | Mesenchymal chondrosarcoma, extraskeletal osteosarcoma |

| Uncertain Differentiation | |

| Intermediate (rarely metastasizing) | Angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma, ossifying fibromyxoid tumor |

| Malignant | Synovial sarcoma, epithelioid sarcoma, clear cell sarcoma of soft tissue, extraskeletal myxoid chondrosarcoma, extraskeletal Ewing’s tumor, intimal sarcoma, extraskeletal osteosarcoma, alveola soft part sarcoma |

| Neurogenic | |

| Malignant (peripheral nerve sheath) | Neurofibrosarcoma, malignant schwannoma |

| Pleuripotential Mesenchymal Tissue | Malignant mesenchymoma |

GCT, germ cell tumor; MFH, malignant fibrous histiocytoma.

Computed tomography (CT)– or ultrasound (US)–guided percutaneous fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy is performed under local anesthesia. An FNA biopsy has low risk of complications but a greater probability of misdiagnosis, and its limitations make it best for suspected recurrent soft tissue tumors or nodal metastases.5,14

A core needle biopsy is often preferred because it has relatively low (~1%) rate of complications, and a much higher diagnostic yield than an FNA biopsy.14–16 Several specimens should be obtained within a soft tissue tumor to ensure adequate tumor tissue for various pathologic stains, electron microscopic studies, cytogenetic analysis and flow cytometric studies. US, CT or gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often used as a guide to determine the best area for biopsy. In addition, the biopsy site should be chosen so that it lays within the area of subsequent en bloc resection. Improper biopsy has been shown to be associated with greater morbidity, complications and changes in clinical course and outcome.17 To prevent tumor seeding, biopsy can be obtained by using a coaxial needle with its tip at the outer margin of the tumor through which the core biopsy needle can be placed within the tumor. An adequacy rate of 93% and an accuracy rate of 95% have been reported with FNA and core needle biopsies.16

In case of a malignant retroperitoneal soft tissue tumor, needle biopsy should not be performed routinely because of the potential danger of transperitoneal tumor spread and track seeding. Exceptions include suspected intra-abdominal nodal involvement in lymphoma and germ cell tumors and for soft tissue tumors where preoperative chemotherapy or radiation is to be used.15

The histologic grade of soft tissue sarcoma best predicts its biologic behavior and is determined by four factors: mitotic index, degree of cellularity, intratumoral necrosis and degree of nuclear anaplasia. A soft tissue sarcoma is graded as low-grade or high-grade malignancy on histopathology. High-grade soft tissue sarcomas can be moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated, or undifferentiated.

Key Points Histopathologic considerations

• According to the WHO, more than 50 histologic subtypes of soft tissue sarcomas exist.

• Needle aspiration or core biopsy under US, CT, or MRI guidance or incisional or excisional biopsy of a soft tissue sarcoma can be performed for histologic diagnosis.

• Histopathologically, a soft tissue sarcoma may be low-grade or high-grade. A high-grade tumor may be moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated, or undifferentiated.

Clinical Evaluation

Soft tissue sarcomas usually present as gradually enlarging, painless masses. Diagnosis of soft tissue sarcoma relies on clinical examination, imaging and histologic analysis. Clinical examination and imaging define tumor relationship with adjoining structures.18–20 Because they are more superficial, soft tissue tumors in distal limbs and head and neck tend to be small; those in thighs, buttocks, and retroperitoneum can be huge.

When evaluating a patient with a soft tissue mass, one must ascertain how long the mass has been present; whether the mass is slow- or fast-growing; the presence of local pain and tenderness; constitutional symptoms; history of prior surgery, radiation, or trauma to the area; and recent use of anticoagulants. The growth rate of a soft tissue sarcoma can often vary with aggressiveness of tumor. However, slow growth does not always imply benignity. It is not uncommon for epithelioid sarcoma to be mistaken for a benign tumor because of its small size, thereby leading to improper management. The presence of local pain, seen in about one third of patients with rapidly growing high-grade tumors, usually indicates poor prognosis.18 Discoloration of overlying skin or variation in size of the soft tissue mass with activity or palpation favors hemangioma. Regional lymph nodes should always be examined for metastatic spread, even though lymphangietic spread of a soft tissue sarcoma is uncommon.

Most soft tissue sarcomas usually expand centrifugally and tend to have a peripheral pseudocapsule of compressed normal soft tissue. However, this pseudocapsule is often infiltrated by tumor.21 As a soft tissue sarcoma grows, it follows the path of least resistance and tends to remain confined to the compartment of origin. Such an intracompartmental soft tissue tumor is bounded by natural anatomic barriers, such as fascial septa, tendon, ligament, cortical bone, articular cartilage and joint capsule. Larger tumors can cause symptoms secondary to increased pressure/stretch on adjoining neurovascular structures. This can result not only in pain but also in paresthesias and edema. With highly aggressive soft tissue tumors, satellite tumor foci (skip metastases) may be found frequently beyond the peritumoral reactive zone within the compartment of origin.21

The presence of a pseudocapsule at the periphery of a soft tissue sarcoma does not confer benignity. A well-marginated soft tissue tumor with a pseudocapsule can be malignant, whereas an infiltrating soft tissue tumor with ill-defined borders, such as desmoid tumor, rarely spreads. Size of a soft tissue tumor may not always distinguish a benign from a malignant soft tissue tumor, as has been pointed out earlier. However, in general, a soft tissue mass smaller than 3 cm in diameter tends to be benign with a positive predictive value of 88%, whereas a soft tissue mass larger than 5 cm in diameter indicates malignancy with sensitivity of 74%, specificity of 59% and accuracy of 66%.22 Extracompartmental extent, involvement of adjacent bone, and encasement of neurovascular bundle are insensitive signs of malignancy because these can also be seen with benign soft tissue tumors, such as hemangioma, desmoid and pigmented villonodular synovitis. A benign soft tissue lesion, such as fibromatosis, may be aggressive in behavior, whereas a well-differentiated liposarcoma is slow-growing. In some cases, both benign and malignant soft tissue tumors may be seen in the same patient. For instance, in a patient with neurofibromatosis, numerous benign soft tissue neurofibromas may coexist with a neurofibrosarcoma, and sometimes, it may be difficult to distinguish between the two.

Key Points Clinical evaluation

• Soft tissue sarcomas present as a localized palpable mass with variable pain and tenderness.

• A soft tissue sarcoma is usually hard in consistency, and when large, it may produce symptoms by compression of adjoining neurovascular bundle.

• When the sarcoma is near a joint, the patient may have limitation in range of motion.

• The size of a tumor does not determine whether it is benign or malignant.

• A rapidly growing tumor usually indicates sarcoma.

• A painful, rapidly growing soft tissue tumor tends to have a poor prognosis.

• Pseudocapsule around a soft tissue sarcoma often harbors malignancy.

Classification and Staging

Soft tissue is derived from mesenchyme and consists of skeletal muscle, fat, fibrous tissue, blood vessels and neurovascular tissue. Soft tissue sarcomas (Greek, sarx means “flesh”) are designated on the basis of the adult tissue they resemble microscopically, and not necessarily on the tissue in which they originate.2 For instance, lipoma designation does not mean that the tumor arose from adipose tissue; instead, it means the tumor contains tissue resembling mature fat. Dedifferentiated soft tissue sarcoma contains poorly differentiated mesenchyme on microscopy and, thus, lacks a specific designation to the tumor. More sophisticated immunohistochemical stains and genetic markers are now available to further classify these undifferentiated soft tissue sarcomas. Only a few of the genetic aberrations that occur in soft tissue sarcomas are congenital; most are acquired spontaneously.23

Staging refers to the evaluation of local and distant spread of tumor and has multiple purposes. It provides a standardized method for determining extent of disease, allows assessment of prognosis, and serves to guide initial treatment decisions. The revised seventh edition of the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) staging system that took effect on January 1, 2010, does not directly take into consideration the histologic subtype, known to be especially important for predicting tumor behavior and metastatic risk. Rather, parameters such as tumor cellularity, differentiation, pleomorphism, mitotic rate, and necrosis are used to assign tumors into one of three possible tumor grades (low-, intermediate-, and high-grade) that indirectly predict a cancers phenotype. (AJCC official web site).

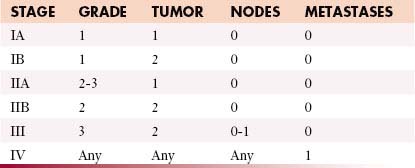

This GTNM system (based on grading, tumor, node and metastases) is shown in Table 37-2.24 However, these criteria do not apply to all soft tissue sarcomas, such as visceral sarcomas and Kaposi’s sarcoma. The recent staging classification has undergone several critical changes. For example, several soft tissue sarcoma subtypes such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), desmoid fibromatosis, and uterine sarcoma, previously included within the general soft tissue sarcoma staging system, now have their own respective staging classification. Conversely, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, angiosarcoma, and extraskeletal Ewing’s sarcoma are newly included with the soft tissue sarcoma staging system.

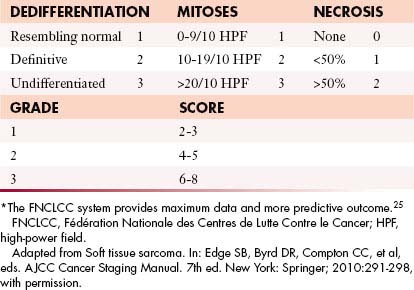

Another change is that tumor depth, previously described as superficial or deep, is no longer used within the latest seventh edition, and the three-tiered grading method advocated by the FNCLCC (Fédération Nationale des Centres de Lutte Contre le Cancer)25 is now preferred over the four-tiered GTNM system (Table 37-3).

Tumor Characteristics: GTNM System

The most important determinants of staging of extremity soft tissue sarcoma are histologic grade and size; both have similar prognostic value26,27 (see Table 37-3). The N stage refers to regional node involvement. Metastatic spread with soft tissue sarcomas is generally hematogenous; however, in fewer than 5% of cases, metastatic spread may occur via lymphatics. The most common tumors that metastasize to regional lymph nodes are synovial sarcoma, epitheloid sarcoma, clear cell sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and angiosarcoma.18 The M stage refers to local or distant metastases. Metastatic potentials for low-grade, intermediate-grade, and high-grade soft tissue sarcomas are 5% to 10%, 25% to 30%, and 50% to 60%, respectively.

In general, staging of soft tissue sarcomas is as follows:

Although the staging system continues to evolve, significant challenges remain to be solved.27 Soft tissue sarcomas of extremities, head and neck, viscera, and retroperitoneum are all staged together, regardless of different surgical approach and outcomes.5 In addition, small size alone is not always determinant of actual biologic behavior of soft tissue tumors. For instance, a small epitheloid or synovial sarcoma often disseminates, whereas a much larger well-differentiated liposarcoma rarely does.

Spectrum of Soft Tissue Sarcomas

The WHO classification of soft tissue sarcomas provides uniformity of tissue diagnosis3 (see Table 37-1). However, this classification is incomplete because it does not include neurogenic sarcomas. In addition, at present, atypical lipoma and well-differentiated liposarcoma, having no potential for distant metastases, are considered histopathologically the same tumor, and not different neoplasms, whereas MFH is now designated as undifferentiated high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma.28,29

A modified WHO classification of soft tissue sarcomas is given in Table 37-1. The most common soft tissue sarcomas in adults are high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma (formerly MFH) 28%, liposarcoma 15%, leiomyosarcoma 12%, synovial sarcoma 10%, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors 6%, whereas rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common soft tissue sarcoma in children.18

Key Points Classification and staging

• Classification of soft tissue sarcomas is based on constituent mesenchymal tissue.

• Dedifferentiated soft tissue tumors contain poorly differentiated mesenchymal tissue on microscopy; thus, they lack specific tissue diagnosis.

• Histologic parameters—tumor cellularity, differentiation, pleomorphism, mitotic rate, and necrosis—are used to predict tumor behavior and metastatic risk and ultimately influence treatment and prognosis.

• The GTNM system, based upon histologic grade, size, regional lymph node involvement, and distant metastases, is used to stage soft tissue tumors.

• Stage I: low-grade tumor without metastases regardless of size; stage II: intermediate- to high-grade tumor without metastases; stage III: large high-grade or node-positive tumor; and stage IV: soft tissue tumor with distant metastases regardless of size or histologic grade.

Imaging

Radiography

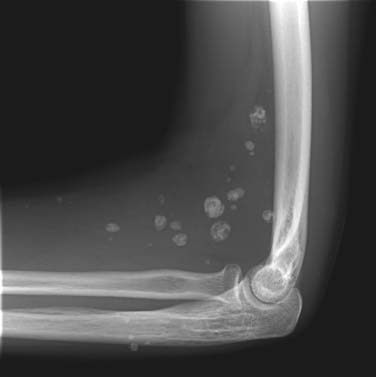

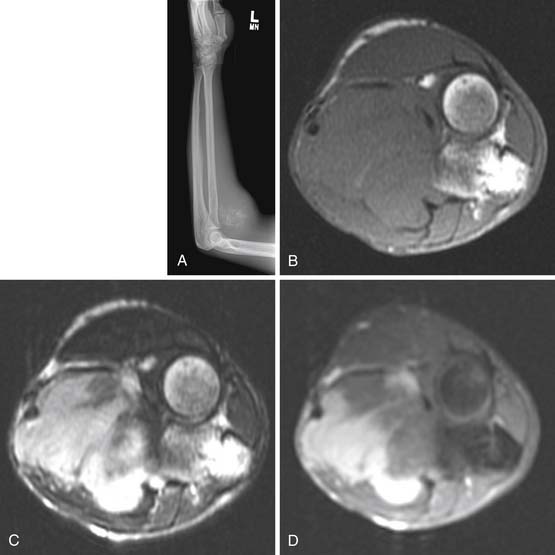

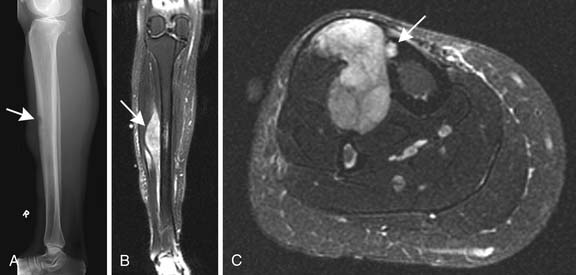

Radiography has a limited role in the diagnosis and staging of soft tissue tumors.19,20,26 Small, deep-seated soft tissue tumors are often difficult to recognize on radiographs, whereas larger soft tissue tumors can be seen because they distort fascial planes and may produce a focal surface bulge (Figure 37-1). Other findings when present on radiographs can be useful in diagnosis. For instance, calcified phleboliths in soft tissues on radiographs indicate a soft tissue hemangioma (Figure 37-2). A soft tissue tumor with calcifications near a joint in a young adult is suggestive of synovial sarcoma (Figure 37-3). A soft tissue lipoma containing radiolucent fat is often diagnosed on radiographs. Radiographs also provide useful information such as erosions, destruction, periosteal reaction, and pressure deformity of an adjoining bone, which may be associated with a soft tissue sarcoma (Figure 37-4).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is considered the imaging modality of choice for localization, characterization, and staging of a soft tissue tumor.20,21,30,31 Although highly sensitive, MRI has limited ability to provide specific tissue diagnosis and to distinguish benign from malignant soft tissue tumors.30–32

MRI provides superb contrast detail of various soft tissues, allows multiplanar imaging capability, and involves no ionizing radiation. It has the ability to assess both soft tissues and bones (Figure 37-5). It is well-suited for postoperative evaluation in the presence of metallic hardware because it produces fewer artifacts than CT. MRI is the best modality to study bone marrow and is equally as capable as CT for detecting cortical bony abnormalities.33 MRI accurately demonstrates anatomic location of a soft tissue mass and its relationship to adjoining neurovascular structures and bone. Dynamic gadolinium-enhanced MRI can be used to guide biopsy needle by distinguishing recurrent tumor or viable residual tumor tissue with early enhancement from poor and delayed enhancement of granulation soft tissue in surgical bed.34 Magnetic resonance spectroscopy may be useful in assessing the response of tumor to chemotherapy where surgical resection of tumor may not be feasible.35 However, MRI is ineffective in the detection of soft tissue calcifications and air, for which radiography and CT are much more superior.33

Technique

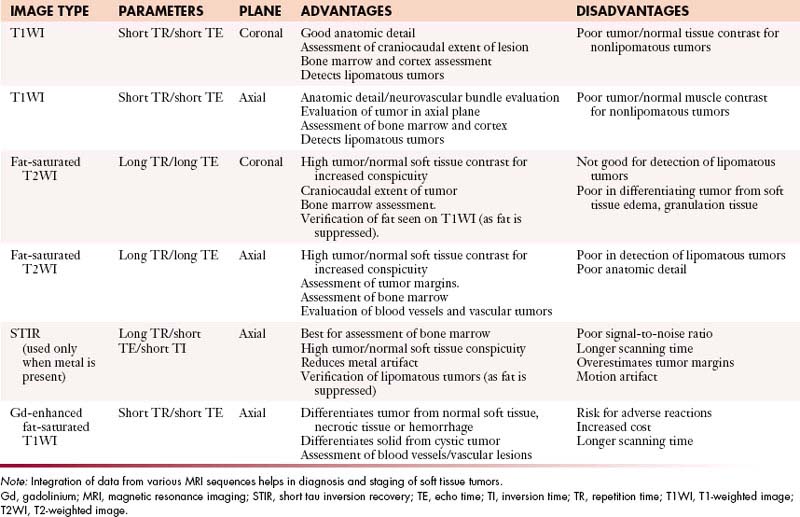

Conventional T1-weighted imaging (T1WI) and T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) spin echo MRI pulse sequences, preferably in the axial and coronal planes, are routinely used for imaging of a soft tissue mass. MRI in additional orthogonal planes, such as sagittal and oblique, can be done, if required. The main disadvantage of the spin echo MRI is relatively long acquisition times, especially for the double-echo T2WI sequences. Fat-suppression T2WI increases tumor–to–background signal intensity differences and demonstrates a bright lesion in a suppressed fat dark background (Figure 37-6). Short tau inversion recovery (STIR) technique can be combined with the standard T1WI and T2WI spin echo sequences because it produces tissue contrast similar to fat-suppression T2WI with a bright lesion within a suppressed fat dark background. STIR imaging enhances tumor conspicuity, but it tends to have a lower signal-to-noise ratio than the standard spin echo imaging and is also more susceptible to motion artifact. It is the best modality for the study of bone marrow disorders, and is used with advantage to reduce metallic saturation artifact in the presence of orthopedic hardware. Additional MRI sequences, such as gradient echo and turbo (fast) spin echo, can be used under special circumstances. The routinely used MRI pulse sequences are provided in Table 37-4.

Table 37-4 Routinely Used Magnetic Resonance Imaging Sequences for Musculoskeletal Soft Tissue Tumors at University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston

Routine use of intravenous gadolinium for contrast-enhanced MRI of soft tissue sarcomas, except in evaluation of hemorrhagic and vascular soft tissue masses, is controversial.36,37 Gadolinium-enhanced MRI can differentiate between solid tumors, such as myxoma and myxoid liposarcoma, and cystic lesions, which have similar MRI appearance on spin echo T1WI and T2WI, by demonstrating nonenhancement of cystic lesions. However, US is the best imaging modality for this purpose. Gadolinium also highlights enhanced viable tumor tissue from nonenhanced necrotic tissue within a soft tissue tumor, thereby facilitating biopsy of tumor tissue or assessment of tumor response to treatment in follow-up MRI studies. However, use of gadolinium adds extra cost and imaging time. It also poses a slight risk of anaphylactic adverse reactions, such as hives and bronchospasm.38,39 Although most of the adverse reactions to gadolinium are mild, at least one death has been reported.40 Rarely, a poorly understood major adverse reaction, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, may occur, especially in patients with impaired renal function.41 As a rule, patients with glomerular filtration rate (GFR) less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 should not be given gadolinium for MRI.

The field of view (FOV) should be large enough to include the entire tumor and also the entire local area for tumor staging. A marker, usually a vitamin E capsule, is routinely placed lightly on the skin surface over the area of interest.

MRA, performed without or with the intravenous administration of gadolinium, is useful in multiplanar assessment of vascular anatomy of a soft tissue tumor.42,43 Fast MRI after bolus intravenous injection of gadolinium, timed with peaked contrast concentration within the tumor, can be used to study the arterial, capillary, and venous phases of blood flow of a soft tissue tumor. MRA can also diagnose vascular tumors and vascular malformations in soft tissues. In most cases, it has replaced conventional angiography in the assessment of the vascular supply of soft tissue tumors.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging Characteristics of Soft Tissue Tumors

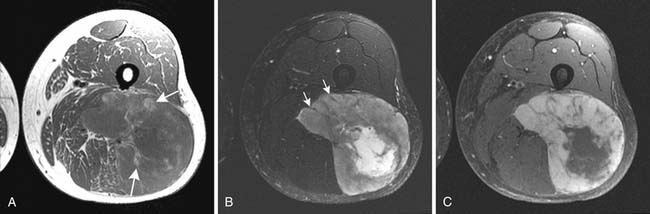

Most soft tissue tumors are hypointense on T1WI and hyperintense on T2WI, and show enhancement on the postcontrast images. In most cases, MRI cannot provide a specific diagnosis, except for a few soft tissue tumors, such as hemangioma, lipoma or fibroma. In almost all other cases, biopsy of soft tissue tumor is required for definitive diagnosis. In addition, MRI cannot reliably differentiate benign from malignant soft tissue tumors.32 Generally, a malignant soft tissue tumor tends to be larger in size, and despite increased blood supply, it quickly outgrows it. Thus, a large malignant tumor often contains areas of necrosis, which impart a nonhomogeneous appearance on the T2WI, STIR and postcontrast T1WI (see Figure 37-5). By contrast, only approximately 5% of benign soft tissue tumors are larger than 5 cm in diameter and most tend to be homogeneously hyperintense on T2WI and STIR with homogeneous enhancement on the postcontrast T1WI. In addition, a superficial soft tissue tumor is usually benign, whereas a deep-seated tumor tends to be malignant. However, small size or superficial location of a soft tissue tumor does not always indicate it to be benign. Similarly, peritumoral soft tissue edema can be seen with both benign and malignant soft tissue tumors.5,44

As a rule, a malignant soft tissue tumor is hypervascular with increased perfusion and, thus, shows increased gadolinium enhancement, but many benign soft tissue tumors, especially vascular tumors, also have increased gadolinium enhancement. Thus, even use of intravenous gadolinium cannot always differentiate a benign from a malignant soft tissue tumor.32,36,37

For subcutaneous soft tissue tumors, except for vascular and neurogenic tumors, the presence of an obtuse angle between the subcutaneous soft tissue tumor and the adjoining superficial fascia has six to seven times greater probability of malignancy than a subcutaneous soft tissue tumor making an acute angle with the superficial fascia.45 In clinical practice, a soft tissue tumor, which is larger than 33 mm in diameter, has intratumoral necrosis with heterogeneous signal on the T2WI, STIR and postcontrast images, causes bony involvement, and entraps the neurovascular bundle, has the highest probability of being malignant.21

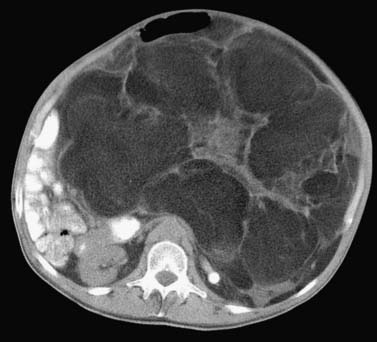

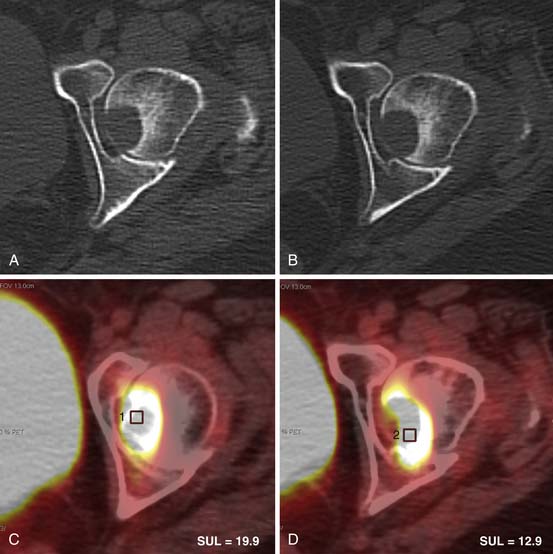

Computed Tomography

CT is the preferred imaging modality for evaluation of bone and mineralized soft tissues.33,46,47 Although CT and MRI are considered equally good for assessment of cortical bone, CT has an advantage over MRI in better demonstrating periosteal reaction, cortical erosions, tumor matrix mineralization, remodeling of bone, and gas in soft tissues. It is also ideal for assessment of areas of the body with complex anatomy, such as the face, pelvis, and foot. The present generation fast multidetector CT scanners are capable of generating high-quality re-formatted multiplanar CT images, three-dimensional CT reconstructions, and even cine CT images, which can be useful to the operating surgeon. CT is especially useful in the postoperative evaluation of patients with metallic orthopedic hardware because beam-hardening artifact can be minimized with present CT imaging techniques, thereby enhancing tissue detail for diagnosis. Contrast-enhanced CT is an alternative choice for imaging when a patient cannot undergo MRI. CT-guided biopsy of a soft tissue mass is routinely obtained. Lastly, CT remains the best modality for detection of pulmonary metastases in staging of soft tissue sarcomas. Contrast-enhanced CT is also routinely used in the detection and follow-up of retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcomas (Figure 37-7).

Positron-Emission Tomography

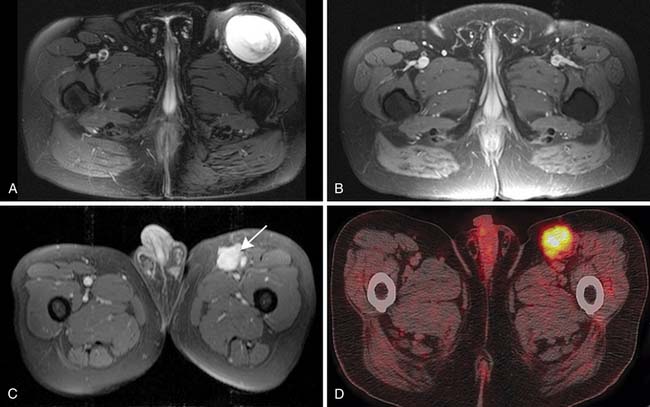

PET provides information about metabolic activity in a soft tissue tumor.48,49 A PET scanner detects positron emission decay from administered radioisotope and generates an image of the entire body. The imaging agent routinely used for this purpose is fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG). Once given intravenously, FDG tagged with proton-emitting radioactive (F-18) fluorine behaves like glucose and reflects glucose metabolic activity in the body. However, unlike glucose, the metabolite of injected FDG is not a substrate for glycolytic enzymes and, therefore, does not decay further. The proton-emitting metabolite trapped within body cells allows subsequent imaging by emitting two 512-KeV gamma energy photons perpendicular to each other. The amount of radiotracer activity within the trapping cell thus reflects its metabolic activity. As a rule, high-grade malignant soft tissue tumors have higher rates of glucose metabolic activity and show increased FDG uptake than benign or low-grade soft tissue malignant tumors. PET is now combined with CT for more precise anatomic correlation of tumor. PET/CT has also been found useful in follow-up of previously treated tumors to assess treatment response (Figure 37-8).49

Ultrasonography

The main role of US is to differentiate a solid from a cystic soft tissue tumor. It is also used to guide biopsy needle for tissue diagnosis. Doppler US can be used for diagnosis of vascular soft tissue tumors and to distinguish malignant soft tissue tumor from benign tumor by evaluating altered intratumoral blood flow.50

Bone Scintigraphy

Key Points Imaging

• Radiography provides information about tumor mineralization and bone involvement, and in case of a lipogenic or vascular ST tumor, it may even suggest specific diagnosis. Chest radiographs are routinely used to detect lung metastases.

• CT is useful in determining size, extent, and cortical bone involvement. It is the best modality to detect tumor mineralization and lung metastases. It is the modality of choice for imaging retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcomas.

• Gadolinium-enhanced MRI is the best modality for staging and characterization of a soft tissue sarcoma by determining its size, extent, associated bone involvement, and status of neurovascular bundle.

• US can differentiate cystic from noncystic soft tissue masses and is often used for guidance of the biopsy needle.

• PET/CT can assess metabolic activity of a soft tissue tumor after treatment.

• Radionuclide scintigraphy is used to detect bony metastases.

Treatment and Prognosis*

Patients with soft tissue sarcoma should be treated at centers that specialize in the treatment of soft tissue tumors because a multidisciplinary approach is required.5,18,21,51 Surgery is the treatment of choice for localized resectable soft tissue sarcoma. The size, location, histologic subtype, and grade will determine whether radiation or chemotherapy is used in the adjuvant or neoadjuvant setting. Approximately one third of the patients with low-grade soft tissue sarcomas will be cured by surgery alone. Limb-sparing surgery has become the norm, and amputations (forequarter, hindquarter, or through-hip) are required in only approximately 5% to 10% of patients with limb soft tissue sarcomas.19,52

Surgical resections can be classified as intralesional (entering the tumor but removing all visible tissue), marginal (through the surrounding pseudocapsule, often leaving microscopic tumor), wide (including a cuff of normal tissue in the resection), and radical (resection of the entire compartment). Radical resections should not be confused with amputations because, depending on the location of the tumor, not all amputations achieve radical or even wide margins. Wide resection is recommended for all soft tissue sarcomas; however, the proximity of the soft tissue sarcoma to neurovascular or visceral structures and patient and family preference can play a role in the actual surgery performed.53,54 For soft tissue sarcomas next to bones or neurovascular structures, careful review of the CT and MRI is necessary to further investigate involvement of these structures. CT is especially useful in evaluation of bony cortex. Often resection of periosteum is required; however, resection of the underlying bone is rarely necessary. MRI is the best imaging modality for evaluation of neurovascular involvement. If neurovascular structures are encompassed by the tumor, resection and neurovascular reconstruction will be necessary, but as is more often the case, these structures tend to reside on the surface of the tumor and opening of the perineurium allows their dissection free from the tumor.

Peritumoral soft tissue edema surrounding soft tissue tumor seen on the T2WI is considered a reactive zone and should be included in the tumor resection.55,56 However, the amount of tissue needed to achieve a wide margin remains controversial. Generally, it is believed that, for definitive resection, all efforts should be made to obtain the widest margins that local anatomy and functional considerations allow; this is often quoted as 2 to 3 cm (when possible). Wide resection with limb salvage provides a local recurrence rate of less than 10%; leaving a positive margin increases the incidence of tumor recurrence up to 90%.57

Radiation can be beneficial in decreasing local recurrence rate and metastases.58,59 Although there is the group of patients with small (<5 cm), low-grade tumors or anatomically accessible tumors in whom surgery alone should be considered, radiation therapy is used as an adjuvant to surgery for the treatment of most other soft tissue sarcomas. For high-grade tumors or large low- to intermediate-grade tumors, surgery combined with radiation therapy is the standard of care. The goal of radiation therapy is to eradicate the microscopic disease that exists beyond the surgical margin. Radiation therapy should be given before or after limb salvage surgery. There is no significant difference in tumor control, development of metastases, and progression-free survival, whether the radiation is given preoperatively or postoperatively. However, preoperative radiation has been shown to be associated with an increase in early wound complications when compared to postoperative radiation. However, it is important to note that this increase in wound complications was seen only in lower extremity tumors, and it did not affect functional outcome or long-term quality of life of patients. Postoperative radiation does require a larger volume of tissue to be irradiated (to encompass the whole resection bed) and a larger radiation dose. Brachytherapy is another option in which a radioactive source is implanted into the tumor via a catheter to reduce local recurrence.60 For those patients who are not operative candidates, definitive treatment with radiation is an option. This requires higher doses, and the success depends on tumor size, treatment duration, and dose given.61 Postoperative radiation is routinely given to the surgical bed for resected tumors with positive margins.58,61

The role of chemotherapy for the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas remains controversial. The sensitivity and response to chemotherapy vary among histologic subtypes. For solitary, high-grade, large lesions, chemotherapy can be considered. In cases in which tumors have metastasized or recurred locally, systemic chemotherapy is often employed.62,63 Such therapies, when used, are chosen taking into consideration both host factors (such as patient age, performance score, organ function) and the factors intrinsic to the soft tissue sarcoma itself (such as tumor subtype and likelihood of chemotherapy response).

Cytotoxic drugs, such as ifosfamide, vincristine, cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin, can be useful for both local and systemic control of tumors and can be given either before or after surgery depending upon the clinical scenario.63,64 When administered as a neoadjuvant, these drugs may facilitate a margin-negative operation that might not otherwise have been possible. Chemotherapy will not, unfortunately, provide a cure to those harboring extensive metastatic disease. However, significant prolongation of life is often possible. Because chemotherapeutic regimens tend to change over time, the latest treatment guidelines should be consulted in caring for soft tissue sarcoma patients: the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) soft tissue sarcoma guidelines have recently been updated and provide a reasonable starting point.

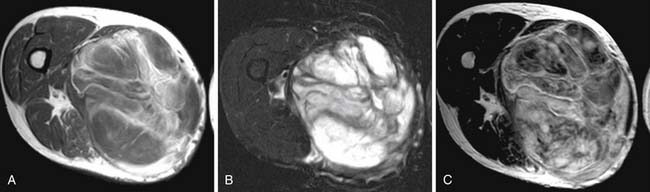

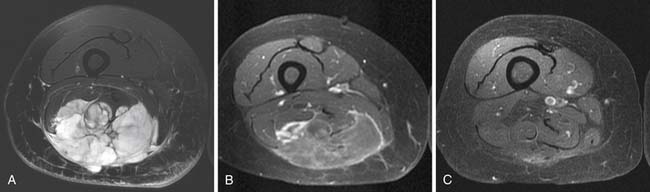

Figure 37-9 illustrates the excellent treatment response of a myxoid malignant fibrohistiocytoma in the right thigh of a patient who received only chemotherapy and radiation treatment.

Key Points Treatment and prognosis

• Treatment depends upon location and staging of a soft tissue sarcoma and requires a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach.

• Surgery of a soft tissue sarcoma can be intralesional, marginal, wide, or radical.

• Small low-grade soft tissue tumors usually require only surgical resection.

• High-grade tumors are treated with surgery and often with adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy.

• Pre- and post-operative radiation may be used to reduce local tumor recurrence.

• Adjuvant chemotherapy is usually given in patients with local tumor recurrence or distant metastases.

Surveillance

Follow-up is an important part of the treatment regimen. The majority of recurrences occur in the first 2 to 3 years. Thus, follow-up is concentrated during this time interval. For the first 2 years, patients are seen every 3 months; for the next 2 years, patients are seen every 4 months; and then at 5 years, the patients are followed every 6 months. Follow-up consists of physical examination and imaging of the site and chest radiograph.5,18 Pulmonary metastases, even when multiple or bilateral, are usually resected with a cure rate of approximately 25% to 30%.5 Patients with unresectable pulmonary or extrapulmonary metastases should receive adjuvant chemotherapy.5,65 Depending on location, US or MRI can provide valuable information. MRI is still the imaging modality of choice, preferably without and with intravenous gadolinium. The presence of an enhancing soft tissue nodule in the surgical bed on the postcontrast MRI is suggestive of recurrent tumor and requires biopsy (see Figure 37-9). The benefit of US is that, if a postoperative nodule is seen in the surgical bed, and recurrence is suspected, immediate biopsy can be performed. For retroperitoneal sarcomas, CT should be done for detection of recurrent and metastatic disease, usually to liver and peritoneum, every 3 to 6 months during the first 2 years after surgery and every 6 months for 3 years thereafter.66,67

Five-year survival rates of patients with limb soft tissue sarcoma for stages I. II, III, and IV are 90%, 70%, 50%, and 10% to 20%, respectively, although these are further affected by site, histologic type, and other factors.5,67 With the current multimodal treatment and sophisticated surgical techniques, the present overall recurrence rate for limb soft tissue sarcomas is less than 10%.5 For retroperitoneal soft tissue tumors, because of high local recurrence rates varying from 40% to 90%, the overall prognosis is poor regardless of the treatment modality, and the five-year survival rates varies from 40% to 52%.68 Large size, high histologic grade, unresectibility, and gross positive margins of resected soft tissue tumor predict worse prognosis with high mortality.5,18

Key Points Surveillance

• Surveillance involves physical examination, obtaining MRI of the surgical bed for local tumor recurrence, and chest radiographs and CT for lung metastases.

• Most recurrences of resected sarcomas occur within the first 2 to 3 years after surgery.

• For the first 2 years, patients are seen every 3 months; for next 2 to 5 years, every 4 months; and thereafter, at every-6-month intervals.

• For retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcomas, abdominal CT is used for staging and surveillance.

New Therapies

Recently, biologically targeted therapies, in part made possible though the discovery of specific oncogenic signalling cascades have been advocated for treatment of some soft tissue tumors.69–72 For instance, tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as imatinib, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR), have been effective in treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors and dermatofibroma protruberance, respectively.70 Similarly, the receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa (NF-κB) and RANK ligand and its cognates, such as denosumab 1, are being used for treating giant cell tumors of tendon sheath and pigmented villonodular synovitis with good results as these tumors are susceptible to the anti-osteoclastic effects of these drugs.69 Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors, such as bevacizumab, have shown promise in treating solitary fibrous tumors, and more recently, alveolar soft part sarcomas.71,72 Finally, insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R) targeted therapies have shown dramatic responses in a subset of Ewing sarcoma patients. It is hoped that such biologically targeted therapies with newer therapeutic agents will become more effective for cancer treatment in future.

1. Kransdorf M.J. Malignant soft-tissue tumors in a large referral population: distribution of diagnoses by age, sex, and location. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:129-134.

2. Enzinger F.M., Weiss S.W. General considerations. In: Enzinger F.M., Weiss S.W. Soft Tissue Tumors. 5th ed. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1995:1-16.

3. Fletcher C.D., Unni K.K., Mertens F. WHO Classification of Tumors: Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon, France: IARC, 2002. 12-18

4. Hajdu S.I. Soft tissue sarcomas: classification and natural history. CA Cancer J Clin. 1981;31:271-280.

5. Morrison B.A. Soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2003;16:285-290.

6. Zahm S.H., Fraumeni J.F.Jr. The epidemiology of soft tissue sarcoma. Semin Oncol. 1997;24:504-514.

7. American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures. Soft Tissue Sarcoma. Atlanta: ACS, 2011. 4

8. Singer S., Nielsen T., Antonescu C.R. Sarcoma of soft tissue and bone. In: DeVita V.T.Jr., Hellman S., Rosenberg S.A. Cancer: Principle and Practice of Oncology. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011:1741-1793.

9. Brady M.S., Gaynor J.J., Brennan M.F. Radiation-associated sarcoma of bone and soft tissue. Arch Surg. 1992;127:1379-1385.

10. McClain K.L., Leach C.T., Jenson H.B., et al. Association of Epstein-Barr virus with leiomyosarcomas in young people with AIDS. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:12-18.

11. Pincus L.B., Fox L.P. Images in clinical medicine. The Stewart-Treves syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:950.

12. Strong L.C., Williams W.R., Tainsky M.A. The Li-Fraumeni syndrome: from clinical epidemiology to molecular genetics. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:190-199.

13. Bertazzi P.A., Consonni D., Bachetti S., et al. Health effects of dioxin exposure: a 20-year mortality study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:1031-1044.

14. Hoeber I., Spillane A.J., Fisher C., Thomas J.M. Accuracy of biopsy techniques for limb and limb girdle soft tissue tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:80-87.

15. Heslin M.J., Lewis J.J., Woodruff J.M., Brennan M.F. Core needle biopsy for diagnosis of extremity soft tissue sarcoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4:425-431.

16. Dupuy D.E., Rosenberg A.E., Punyaratabandhu T., et al. Accuracy of CT-guided needle biopsy of musculoskeletal neoplasms. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171:759-762.

17. Mankin H., Mankin C.J., Simon M.A. The hazards of the biopsy revisited. Minutes of the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:656-663.

18. Cormier J.N., Pollock R.E. Soft tissue sarcomas. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:94.

19. Clark M.A., Fisher C., Judson I., Thomas J.M. Soft-tissue sarcomas in adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:701-711.

20. Kransdorf M.J., Murphey M.D. Radiologic evaluation of soft-tissue masses: a current perspective. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:575-587.

21. De Schepper A.M., De Beuckeleer L., Vandevenne J., Somville J. Magnetic resonance imaging of soft tissue tumors. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:213-222.

22. Tung G., Davis L.M. The role of magnetic imaging in the evaluation of the soft tissue mass. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1993;24:239-308.

23. Kruzelock R.P., Hansen M.F. Molecular genetic and cytogenetics of sarcomas. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1995;9:513-540.

24. Greene F.L., Page D.L., Fleming F.D., et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer: Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed. New York: Springer; 2002:221-226.

25. Coindre J.-M. Grading of soft tissue sarcomas: review and update. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1448-1453.

26. Coindre J.M., Terries P., Bui N.B., et al. Prognostic factors in adult patients with locally controlled soft tissue sarcoma. A study of 546 patients from French Federation of Cancer Centers Sarcoma Group. J Clin Oncol. 1998;14:869-877.

27. Ramanathan R.C., A’Hern R., Fischer C., Thomas J.M. Modified staging system for extremity soft tissue sarcomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:57-69.

28. Vilanova J.C., Woertler K., Narvaez J.A., et al. Soft-tissue tumors update: MR imaging features according to the WHO classification. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:125-138.

29. Murphey M.D. World Health Organization classification of bone and soft tissue tumors: modifications and implications for radiologists. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol. 2007;11:201-214.

30. Sundaram M., McGuire M.H., Herbold D.R. Magnetic resonance imaging of soft tissue masses: an evaluation of fifty-three histologically proven tumors. Magn Reson Imaging. 1988;6:237-248.

31. Totty W.G., Murphy W.A., Lee J.K.T. Soft-tissue tumors: MR imaging. Radiology. 1986;160:135-141.

32. Berquist T.H., Ehman R.L., Ding B.F., et al. Value of MR imaging in differentiating benign from malignant soft-tissue masses: study of 95 lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;155:1251.

33. Panicek D.M., Gatsonis C., Rosenthal D.I., et al. CT and MR imaging in the local staging of primary malignant musculoskeletal neoplasms: report of the Radiology Diagnostic Oncology Group. Radiology. 1997;202:237.

34. Mirowitz S.A., Totty W.G., Lee J.K.T. Characterization of musculoskeletal masses using dynamic Gd-DTPA enhanced spin-echo MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1992;16:120-125.

35. Vaidya S.J., Payne G.S., Leach M.O., Pinkerton C.R. Potential role of magnetic resonance spectroscopy in assessment of tumour response in childhood cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:728-735.

36. Beltran J., Chandnani V., McGhee R.A., Kursungoglu-Brahme S. Gadopentetate dimeglumine-enhanced MR imaging of the musculoskeletal system. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:457-466.

37. Benedikt R.A., Jelinek J.S., Kransdorf M.J., et al. MR imaging of soft-tissue masses: role of gadopentetate dimeglumine. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1994;4:485-490.

38. Tisher S., Hoffman J.C. Anaphylactoid reaction to IV gadopentetate dimeglumine. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1990;174:17-23.

39. Takebayashi S., Sugiyama M., Nagase M., Matsubara S. Severe adverse reaction to IV gadopentetate dimeglumine. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;160:659.

40. Jordan R.M., Mintz R.D. Fatal reaction to gadopentetate dimeglumine. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:743-744.

41. Sadowski E.A., Bennett L.K., Chan M.R., et al. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: risk factors and incidence estimation. Radiology. 2007;243:148-157.

42. Dumoulin C.L., Hart H.R. Magnetic resonance angiography. Radiology. 1986;161:717.

43. Glickerman D.J., Obregon R.G., Schmiedl U.P., et al. Cardiac-gated MR angiography of the entire lower extremity: a prospective comparison with conventional angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:445-451.

44. Beltran J., Simon D.C., Katz W., Weis L.D. Increased MR signal intensity in skeletal muscle adjacent to malignant tumors: pathologic correlation and clinical relevance. Radiology. 1987;162:251-255.

45. Galant J., Marti-Bonmati L., Soler R., et al. Grading of subcutaneous soft tissue tumors by means of their relationship with the superficial fascia on MR imaging. Skeletal Radiol. 1998;27:657-663.

46. Weekes R.G., McLeod R.A. Reiman Pritchard DJ. CT of soft-tissue neoplasms. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;144:355-360.

47. Demas B.E., Heelan R.T., Lane J., et al. Soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities: comparison of MR and CT in determining the extent of disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150:615-620.

48. Bredella M.A., Caputo G.R., Steinbach L.S. Value of FDG positron emission tomography in conjunction with MR imaging for evaluating therapy response in patients with musculoskeletal sarcomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;179:1145-1150.

49. Bastiaannet E., Groen H., Jager P.L., et al. The value of FDG-PET in the detection, grading and response to therapy of soft tissue and bone sarcomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30:83-101.

50. Bodner G., Schocke M.F., Rachbauer F., et al. Differentiation of malignant and benign musculoskeletal tumors: combined color and power Doppler US and spectral wave analysis. Radiology. 2002;223:410-416.

51. Valle A.A., Kraybill W.G. Management of soft tissue sarcomas of the extremity in adults. J Surg Oncol. 1996;63:271-279.

52. Vraa S., Keller J., Nielsen O.S., et al. Prognostic factors in soft tissue sarcomas: the Aarhus experience. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1876-1882.

53. Pitcher M.E., Thomas J.M. Functional compartmental resection for soft tissue sarcomas. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1994;20:441-445.

54. Clark M.A., Thomas J.M. Amputation for soft-tissue sarcoma. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:335-342.

55. Bowden L., Booher R.J. The principles and technique of resection of soft parts for sarcoma. Surgery. 1958;44:963-976.

56. Watson D.I., Coventry B.J., Langlois S.L., et al. Soft-tissue sarcoma of the extremity: experience with limb-sparing surgery. Med J Austral. 1994;160:412-416.

57. Gerrand C.H., Wunder J.S., Kandel R.A., et al. Classification of positive margins after resection of soft-tissue sarcoma of the limb predicts the risk of local recurrence. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:1149-1155.

58. Yang J.C., Chang A.E., Baker A.R., et al. Randomized prospective study of the benefit of adjuvant radiation therapy in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas of the extremity. J Clin Oncol. 1998;6:197-203.

59. O’Sullivan B., Ward I., Catton C. Recent advances in radiotherapy for soft-tissue sarcoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2003;5:274-281.

60. Pollack A., Zagars G.K., Goswitz M.S., et al. Preoperative vs. postoperative radiotherapy in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas: a matter of presentation. Int J Rad Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:563-572.

61. Kepka L., Delany T.L., Suit H.H., Goldberg S.I. Results of radiation therapy for unresected soft-tissue sarcomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:852-859.

62. Tepper J.E., Suit H.D. Radiation therapy alone for sarcoma of soft tissue. Cancer. 1985;56:475-479.

63. Santoro A., Tursz T., Mouridsen H., et al. Doxorubicin versus CYVADIC versus doxorubicin plus ifosfamide in first-line treatment of advanced soft issue sarcomas: a randomized study of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Soft Tissue and Bone Sarcoma Group. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1537-1545.

64. O’Byrne K., Steward W.P. The role of adjuvant chemotherapy in the treatment of adult soft tissue sarcomas. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1998;27:221-227.

65. Billingsley K.G., Burt M.E., Jara E., et al. Pulmonary metastases from soft tissue sarcoma: analysis of patterns of disease and postmetastasis survival. Ann Surg. 1999;229:602-612.

66. Lewis J.J., Leung D., Woodruff J.M., et al. Retroperitoneal soft-tissue sarcoma: analysis of 500 patients treated and followed at a single institution. Ann Surg. 1998;228:355-365.

67. Catton C.N., O’Sullivan B.J., Kotwall C., et al. Outcome and prognosis in retroperitoneal soft tissue sarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;29:1005-1010.

68. Lewis J.J., Leung D., Casper E.S., et al. Multifactorial analysis of long-term follow-up (more than 5 years) of primary extremity sarcoma. Arch Surg. 1999;134:90-194.

69. Thomas D., Henshaw R., Skubitz K., Chawla S. Denosumab in patients with giant-cell tumour of the bone: an open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:275-280.

70. Gardner K., Judson I., Leahy M., et al. Activity of cediranib, a highly potent and selective VEGF signaling inhibitor, in alveolar soft part sarcoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:10523.

71. Sleijfer S., Ray-Coquard I., Papal Z., et al. Pazopanib, a multikinase angiogenesis inhibitor, in patients with relapsed or refractory advanced soft tissue sarcoma: a phase II study from the European organisation for research and treatment of cancer-soft tissue and bone sarcoma group (EORTC study 62043). J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3126-3132.

72. Tolcher A.W., Sarantopoulos J., Patnaik A., et al. Phase I, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic study of AMG 479, a fully human monoclonal antibody to insulin-like growth factor receptor 1. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5800-5807.