Soft tissue injuries and burns

Soft tissue injuries

Soft tissue injuries are defined here as cuts, lacerations, crushing injuries, missile injuries and impalements not involving bone or body cavities. The priority for treating soft tissue injuries depends on the primary survey determined by the ABCDE system (Ch. 15).

The management of a soft tissue injury depends upon the following factors:

• The mechanism of injury (e.g. penetrating knife wounds, lacerations in road crashes, blast injuries, gunshot and missile injuries, burns, bites)

• The extent and depth of wounds

• The types of tissue involved including nerves and blood vessels

• The extent of tissue devitalisation

• Any contamination (e.g. with road dirt, soil or potential bacterial inoculation with animal or human bites)

Intermediate soft tissue injuries

Foreign bodies: The history of the injury can indicate the likelihood of foreign bodies being retained in the wound. The main types are agricultural and road dirt, wood splinters, and glass and metal fragments. Plain radiology reveals metal and usually glass (see Fig. 17.1) but a negative X-ray does not exclude its presence. Remember that a foreign body unrecognised at the time may result in litigation later.

Flap lacerations: Relatively minor trauma to the tibia commonly produces a V-shaped flap laceration (Fig. 17.2) particularly in older patients or in patients on long-term corticosteroids. If untreated, this injury habitually fails to heal because of poor blood supply to flap and underlying tissue. Attempting to suture or tape a flap into place increases tension, causing ischaemia, tissue loss and ulceration. The most effective management is early excision and immediate split skin grafting. This can be performed under local anaesthesia and takes an average of 2 weeks to heal.

Facial lacerations: Minor facial lacerations heal well and can be primarily sutured in the accident department after careful cleaning. Infection is rare because of the excellent blood supply. Even ragged skin edges do not become devitalised and trimming is rarely necessary. The main consideration is the cosmetic outcome, so great care should be taken with technique, employing general anaesthesia if necessary. Complex lacerations, lacerations across the lip margin or eyelid and areas of substantial skin loss, especially on children and young people, should ideally be managed by plastic surgeons (see next section).

Scalp lacerations: With scalp lacerations, brain injury and skull fracture must be excluded and then determine whether the aponeurotic layer (galea) has been breached. Haemostasis must also be achieved; it is easy to underestimate blood loss from scalp lacerations, sometimes sufficient to cause hypovolaemic shock in the elderly. Assessment and thorough exploration is made easier by shaving the wound edges; large lacerations may need exploring under general anaesthesia. If the aponeurosis is breached, it should be repaired separately to prevent a subaponeurotic haematoma vulnerable to infection. Care should be paid to haemostasis from major scalp blood vessels lying in the superficial fascia between dermis and aponeurosis. Dense collagenous bands cross the area and can prevent torn vessels contracting, hindering the spontaneous arrest of bleeding. Torn vessels need to be individually ligated or sutured.

Major soft tissue injuries

Major injuries of soft tissues alone requiring hospital treatment are uncommon and can be classified as in Box 17.1. A primary survey (Ch. 15) determines the order injuries are managed, with life-threatening injuries treated first. For other injuries, the urgency depends on the potential for deterioration (e.g. blood loss, ischaemia or loss of an eye), the risk of infection and the availability of the necessary specialists. Contused or contaminated wounds need early cleansing and excision of all devitalised tissue (debridement), usually under GA. If substantially contaminated, wounds are often left unsutured to prevent wound infection and are then sutured a few days later by delayed primary closure. Less commonly, wounds are left open and are allowed to heal by secondary intention (see Ch. 3, p. 36). Wounds involving skin loss may need early skin grafting.

Injury to a vital part of the body

Eye: Injuries greater than ‘sand in the eye’ are best managed by ophthalmic specialists who require a slit lamp and other instruments to assess the injury. Typical injuries include abrasions to the cornea, penetrating injuries (dart or pellets) and firework injuries.

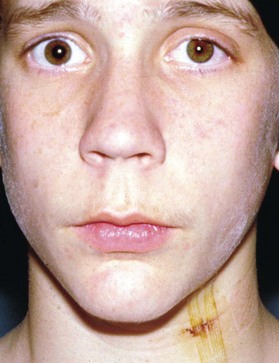

Neck: Penetrating injuries to the neck must be treated with respect. Vital structures are concentrated here and may be injured. These include major arteries and veins (carotid, jugular, subclavian, vertebral), the brachial plexus, some cranial nerves, the cervical sympathetic chain (see Fig. 17.3), and lung and pleura.

Lacerations to the limbs and hands: (for Traumatic amputation, see p. 236)

The main considerations with this type of injury are:

• Possible nerve, tendon or vascular injury—assessment includes testing sensation, movement, peripheral pulses and tissue perfusion (i.e. pulses, warmth, colour, capillary refilling after blanching). Tendon and nerve injuries are covered below

• Tissue viability—particularly important in crush injuries and flap lacerations such as in the pretibial area (see above)

• Risk of infection—the fingers and hands are vulnerable to infection of pulp spaces and the deep palmar space. Wounds need antibiotic prophylaxis against staphylococci and streptococci (e.g. flucloxacillin plus amoxicillin). They also need meticulous cleansing and exploration, if possible by a specialist hand or plastic surgeon. Injuries from bites (especially by dogs or humans) and bones (usually in meat workers) almost invariably become infected (see below).

Extensive facial lacerations: Facial injuries should be thoroughly cleaned and examined under local or general anaesthesia to determine the extent of the damage before repair; ideally within 12 hours of injury. Facial wound edges need minimal trimming. Important anatomical boundaries should be aligned first; these include the vermilion border of the lip, the rim of the eyelid and the eyebrow. Tissue layers should then be approximated individually—mucosa, muscle, cartilage and skin. Parotid duct injury should be considered in deep lacerations of the cheek and the duct repaired if possible. Photographic documentation is useful to help the patient appreciate the extent of injury and to provide an accurate record of progress.

Vascular injuries involving blood loss or ischaemia

Compartment syndrome: The muscles of the leg below the knee and in the forearm lie within rigid fascial compartments. Delayed restoration of blood flow after ischaemia leads to reperfusion injury, which allows protein-rich fluid to leak from damaged capillaries. The intra-compartmental pressure rises (normally in the range of 0–10 mmHg) which compromises venous flow and later reduces capillary flow. This initiates a vicious circle that exacerbates the ischaemic insult and further increases the pressure. Arterial inflow is not usually impaired but compartment syndrome rapidly leads to irreversible nerve ischaemia and muscle necrosis.

Animal-associated soft tissue injuries

Snakebite: Poisonous snakes are a hazard in many areas, although deaths from snakebite are rare. Snakebites are most common where dense human populations coexist with large snake populations (e.g. South-East Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and tropical America). Highly dangerous snakes include the Australian brown snake; Russell’s viper and cobras in southern Asia; carpet vipers in the Middle East; and coral snakes and rattlesnakes in the Americas. The venom of a small or immature snake can be even more concentrated than that of larger ones; therefore all snakes should be left well alone. Less than half of all snakebite wounds actually contain venom, but travellers are advised to seek immediate medical attention whenever a bite breaks the skin. First-aid measures should include immobilising the affected limb and applying a pressure bandage that does not restrict limb perfusion (not a tourniquet), then moving the victim quickly to a medical treatment centre. Incision of the bite is not recommended. Specific therapy varies and should be left to the judgement of experienced local emergency personnel.

Arthropod bites and stings: The bites and stings of some arthropods (which include insects) can cause unpleasant reactions. Travellers should seek medical attention if a spider or insect bite or sting causes excessive redness, swelling, bruising or persistent pain. Patients with a history of severe allergic reactions to bites or stings should consider carrying an adrenaline (epinephrine) autoinjector (EpiPen). Many insects and arthropods can transmit communicable diseases, even without the traveller being aware of a bite, particularly when camping or staying in rural accommodation. Travellers to many parts of the world should be advised to use insect repellents containing DEET, protective clothing, and mosquito netting around beds at night. Stings from scorpions can be painful but are seldom dangerous except in infants and children. Exposure to scorpion stings can be avoided by sleeping under mosquito nets and by shaking clothing and shoes before putting them on.

Animal bites: Domestic pets cause more bites than wild animals, with dogs more likely to bite than cats; however, cat bites are more likely to become infected. Their sharp pointed teeth cause puncture wounds and lacerations that may inoculate bacteria deeply. In Adelaide, about 6500 people are injured each year by dog attacks and 800 seek hospital treatment (7.3 per 10 000 population). Some 90% of children who were bitten suffered head and facial bites. In the USA, dog bites cause about 44 000 facial injuries requiring hospital treatment and 10–20 people are killed each year. This is about 1% of all emergency room visits. In the UK there was an average of 2.3 fatalities a year between 1999 and 2004. Unfortunately, most fatalities are in young children where bites to the face, neck or head are extremely hazardous. Children are often bitten in these areas because of their small stature.

The principles of treatment of bite wounds are inspection, debridement, irrigation and closure:

• Wounds should be inspected to identify deep injury and devitalised tissue. This nearly always requires a general or regional anaesthetic. Care should be taken to visualise the deepest part of the wound and to examine the wound through the range of motion

• Debridement is an effective means of minimising infection. Devitalised tissue, particulate matter and clots should be removed, as with any foreign body. Clean surgical wound edges result in smaller scars and promote faster healing

• Irrigation also helps prevent infection. A 19-gauge blunt needle and a 50 ml syringe provide enough pressure and volume to clean most wounds. In general, 100–200 ml of irrigation solution per cm3 of wound is required. Large, dirty wounds need to be irrigated in the operating theatre. Saline solution is effective and inexpensive

• Primary closure can be considered in clean bite wounds or wounds that can be cleansed effectively. Others are best treated by delayed primary closure. Facial wounds are at low risk for infection, even if closed primarily. Bite wounds to the lower extremities, bites where there is a delayed presentation, or those in immunocompromised patients should generally be left open

Types of infection: Animal saliva is heavily contaminated with bacteria; over 130 disease-causing microorganisms have been isolated from dog and cat bites, thus nearly all infections are mixed. In rabies areas, bites from non-immunised domestic animals and wild animals carry the risk of rabies and the need for prophylaxis should be considered, in addition to tetanus prophylaxis. While local infection and cellulitis are the leading causes of morbidity, sepsis is a potential complication of bite wounds. Meningitis, osteomyelitis and septic arthritis are additional concerns in bite wounds. Rabies is a generally fatal complication. However, the three infections mentioned below are probably the most significant:

Pasteurellosis: Pasteurella multocida is a bacterium carried naturally by most mammals in their mouths, including healthy cats, dogs and rabbits, and by some birds and fish. The organism is responsible for the most common bite-associated infection. The first signs of pasteurellosis usually occur within 2–12 hours of the bite and include pain, reddening and swelling of the area around the bite. Pasteurellosis can progress quickly, spreading from the bitten area, and may cause flu-like symptoms such as fever, headaches, chills and swollen glands. If left untreated, it can cause pneumonia or systemic sepsis and, on rare occasions, death.

Gunshot, missile and stab wounds

Gunshot wounds and missile injuries need special attention. High-energy missiles may cause a small entry wound but produce havoc within (see Ch. 15). X-rays need to be taken and wounds explored under general anaesthesia.

Traumatic amputation of digits or limbs

Principles of digit and limb replantation surgery: Complete amputation of digits is common, especially in industrial accidents, but sometimes whole limbs are severed. With clean-cut injuries, it is possible to reattach the amputated part using microsurgery to join the vessels and nerves. This cannot be done after crush or avulsion injuries or in grossly contaminated wounds. Even in ideal cases, recovery is slow and usually incomplete, necessitating many months away from work and much rehabilitation effort. Therefore, replantation should never be undertaken without carefully evaluating the likely benefits and ensuring the patient is fully involved in the decision. In digital amputation, the greatest disability results from loss of the thumb. Single digits are rarely replanted (except for example in a musician) because the remaining fingers rapidly adapt to the loss and rehabilitation is faster.

At the scene of the injury, the severed digit should be washed gently to remove obvious dirt and placed in a plastic bag which is then placed inside a second plastic bag containing ice or frozen peas. In this way it can be successfully preserved for up to 12 hours.

Crush injuries

Diagnostic criteria for crush syndrome include:

• A crushing injury to a large mass of skeletal muscle

• Sensory and motor disturbances in the compressed limb

• Swelling and tenseness of the limb a few hours later

• Myoglobinuria and/or haematuria

• Elevated serum creatine kinase (CK) with a peak greater than 1000 U/L

• Renal insufficiency hours or days later. This may manifest with oliguria (urine output less than 400 ml in 24 hours), decreased plasma calcium concentration and elevated plasma urea, creatinine, uric acid, potassium and phosphate

Presentation: Crush syndrome presents with profound shock. A limb trapped will be pulseless on release; later it becomes red, swollen and blistered with loss of sensation and muscle power. Reperfusion injury causes compartment syndrome after release of compression. Once the compartment pressure exceeds capillary perfusion pressure (about 30 mmHg), tissues in the compartment become ischaemic.

Peripheral nerve injuries

Anatomy: In a peripheral nerve trunk, individual axons are sheathed in endoneurium and groups are bundled into fascicles. Each fascicle is covered in tough perineurium composed of collagen and elastin and may contain sensory and motor axons. A peripheral nerve trunk consists of a number of fascicles in a matrix of epineurium which also coats the nerve. Fascicles divide repeatedly along the course of a nerve, communicating with each other and intermixing rather than running neatly in parallel. This means the arrangement and type of axons and fascicles in one cross-section of the nerve may be very different from that in an adjoining cross-section. The difficulty of aligning the proximal with the distal arrangement is an important reason why functional recovery is poor if a segment of nerve is lost and has to be replaced with a nerve graft.

Types of injury: Nerve injuries were classified by Seddon in 1943:

• Neuropraxia is the mildest injury, where nerve continuity is preserved and only transient functional loss occurs. Recovery occurs within 6–8 weeks, without Wallerian axonal degeneration. The lesion is caused by compression, blunt impact or nearby low-velocity missile injuries and the injury is probably biochemical. Motor nerves are more sensitive to damage than sensory nerves and autonomic function is often retained

• Axontmesis occurs when there is interruption of axon and its myelin, but perineurium and epineurium are preserved. Axontmesis results from more severe crush injury or contusion; axonal continuity is lost and complete denervation occurs but supporting structures remain intact. Electromyography (EMG) confirms muscle denervation distal to the injury. Recovery eventually takes place by axon regeneration and is likely to be complete

• Neurontmesis involves complete functional disconnection and occurs with severe contusion, stretching or laceration of a nerve. Axons and encapsulating connective tissues lose continuity and motor, sensory and autonomic functions are completely lost, and rarely recover without surgical intervention. The nerve is not usually completely severed but suffers internal structural disruption. In such cases, axonal regeneration causes fusiform swelling of the injured segment. If the nerve is divided, fibroblast proliferation produces dense fibrous scarring which inhibits sprouting axons from entering distal tubules; this seriously impairs nerve regeneration

Nerve regeneration: In axontmesis, calcium-mediated Wallerian (or antegrade) degeneration of the distal axon and myelin occurs early on. Within a few days, sprouting begins from the ends of proximal axons. Regenerating fibres eventually cross the injury site and then progress distally at 1–2 mm a day through undamaged tubules which provide a precise path for reinnervation of target organs.

Clinical types of nerve injury:

Compression: Compression affects the largest myelinated fibres most. Motor control is lost first and discrete sensation follows. The underlying cause is probably ischaemia; large myelinated fibres are more susceptible to this than smaller unmyelinated ones. In partial injuries, smaller pain-bearing and sympathetic fibres are often preserved, causing pain and hyperaesthesia in the nerve distribution. Compression injuries include so-called ‘Saturday night palsy’, where the radial nerve becomes compressed over the back of a seat in a patient who passes out under the influence of alcohol. Total loss of motor and sensory function is likely to occur. Adverse effects are spontaneously reversible unless ischaemia persists for more than 8 hours.

Traction: Traction is the most common mechanism of nerve injury and is often associated with fracture or dislocation. Nerves have little elasticity and can only stretch 4% without injury. Luckily, most traction injuries are self-limiting and have a good prognosis; as many as 90% achieve good or fair recovery. The prognosis is worse when vascular trauma or open fractures are present, with only 65% recovering useful function.

Laceration: Lacerations such as those caused by a knife blade comprise up to 30% of serious nerve injuries. Exploration and repair is recommended in most cases.

Missile injury: Low-velocity gunshot missiles are less likely to sever nerves than sharp lacerations. However, about 70% of missile wounds that require exploration for other reasons demonstrate complete or partial transsection of a nerve. In high-velocity missile injuries, cavitation of soft tissues can produce nerve stretch injuries.

Direct repair: A clean sharp division of a nerve by a knife wound should be repaired by primary anastomosis within 24 hours of injury. Simple epineural repair involves re-approximation of the nerve ends using a circumferential line of sutures. This is technically easier than fascicular repair which involves microsurgical anastomosis of fascicles or groups of fascicles. Results of epineural repair are often good if the fascicular patterns at the cut ends are similar and where anatomic distortion is minimal. Even for proximal nerve trunk repair where a plexiform layout of fibres is more likely, the chances of the correct type of axons passing down the proper fascicles appear to be as good as in fascicular repair. Epineural repair is also stronger and resists tension better. With compression, stretching or contusion injuries, repair should be undertaken between 8 weeks, and 3 months of injury if there is no evidence of natural recovery.

Cable grafting: Autologous nerve grafting is needed if there is a large gap in a nerve. The most commonly used donor nerve is the sural, a large sensory nerve running down the posterior calf to the lateral dorsum of the foot. Several ‘cables’ are usually fashioned and attempts made to match proximal and distal fascicles. The plexiform and mixed nature of fascicles makes full recovery difficult to achieve.

Results of nerve repair: Assuming good technique, the following factors improve the prognosis for recovery after nerve repair:

• The repair involves purely sensory or motor nerves, e.g. the functional result of a severed peroneal nerve repair (motor) is likely to be better than an equivalent median nerve repair (mixed)

• The lesion is distal rather than proximal because distal trunks have a more linear arrangement

• The patient is younger; children have better results than adults, and younger adults better than older adults

Burns

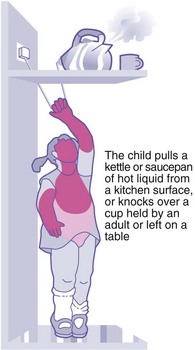

Two-thirds of burns occur in the home and one third largely in industrial accidents. Around 60% of domestic burns are associated with cooking. Half of all deaths in domestic fires occur between 10 p.m. and 8 a.m. and excess alcohol often plays a role. Fireworks and bonfires are frequent causes of domestic burns. Most burns are preventable. Young children and the elderly are at greatest risk and also suffer disproportionate mortality. There is a male predominance except in the elderly; 10% of those burnt are over 65, often as a result of immobility, slowed reactions and decreased dexterity placing them at risk from scalds, contact burns and flame burns. Twenty per cent of all burns occur in children under the age of 4; 70% are scalds caused by spilling hot liquids or by exposure to hot bath water. Toddlers frequently pull containers or cups of hot liquid over themselves from cookers and tables which burn the outstretched arm, face, neck and front of the chest and can cover a large area (see Fig. 17.4).

Fig. 17.4 Typical pattern of burns in a young child

The child pulls a teapot or cup of hot liquid from a table or when being held by a seated adult. The area shaded pink is typically burnt

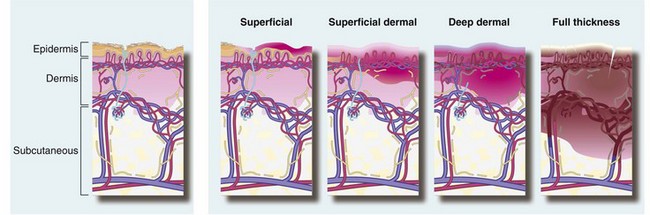

Teenagers are often burnt as a result of illicit activities, e.g. with petrol, explosives or high tension electricity. Overall, 60% of burns occur between the ages of 15 and 64, of which half are flame burns, often with inhalational injury; burns tend to be deep dermal or full thickness (see Fig. 17.5).

Fig. 17.5 Classification of depth of burns

Erythema—red, dry skin that easily blanches then rapidly refills (not illustrated here)

Superficial—red, moist wound that blanches and rapidly refills

Superficial dermal—pale, dry, blanching wound that regains colour slowly

Deep dermal—mottled cherry red and does not blanch (fixed capillary staining). The blood is thrombosed and fixed in damaged capillaries in the deep dermal plexus

Full thickness—dry, leathery or waxy, hard wound that does not blanch. In extensive burns, full thickness burns can be mistaken for unburnt skin

Pathophysiology of burns

Systemic effects (Box 17.2)

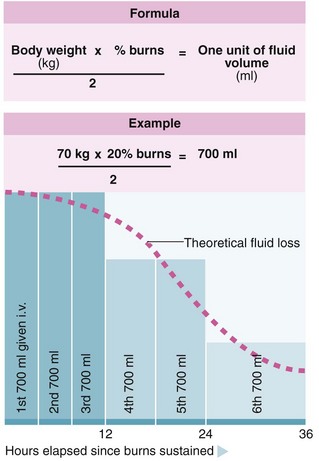

Extensive burns cause large fluid losses. Epidermal destruction removes the barrier that normally prevents evaporation of body water. In addition, inflammation causes exudation of protein-rich fluid into the extracellular space causing oedema and blisters. The large volumes lost need to be replaced urgently (see Fig. 17.7, below), with the amount lost depending on burn area rather than depth. Once 30% of the body surface area is burnt, particularly if there is necrotic tissue, inflammatory mediators and cytokines spill into the circulation, causing a systemic inflammatory response. This provokes a generalised rise in capillary permeability, escalating the volume of plasma leaving the circulation into the ‘third space’. Fluid losses are greatest in the first few hours but continue for at least 36 hours.

Assessment of the burnt patient

Calculating the burnt area

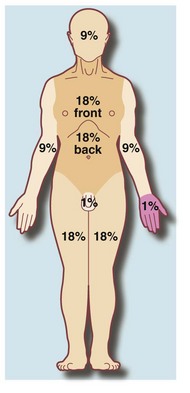

All of the burnt area needs to be exposed sequentially, ensuring the patient is kept warm. For adults, Wallace’s rule of nines (Fig. 17.6) is fairly reliable for medium to large areas and is quick, but is inaccurate in children. Another method is to use the patient’s palm and finger area to indicate 1% of body surface area. This is useful for small burns, and in very large burns where the unburnt area is measured. The most accurate method is to use Lund and Browder charts which compensate for variations in body shape with age; the charts are also accurate in children.

Fig. 17.6 Rule of nines

Wallace’s rule for estimating the percentage of the skin surface area burnt. A useful alternative estimate is that the area of the patient’s own palm plus fingers is approximately 1% of the total skin area.

Depth assessment is not relevant for calculating fluid resuscitation but is important for management of the burn. Figure 17.5 (p. 240) explains a widely used classification of depth, detailed below. In essence, partial thickness burns are capable of regenerating skin from preserved dermal adnexae whereas full thickness burns regenerate slowly from the edges and are likely to need skin grafting. By way of preliminary assessment, if the burnt area is erythematous, blanches on pressure and retains pinprick sensation, it is partial thickness; charred skin or thrombosed skin vessels invariably indicate a full thickness burn.

Partial thickness burns may be classified as follows:

• Superficial burns—affect the epidermis but not the dermis, e.g. sunburn

• Superficial dermal burns—destroy the epidermis and upper dermal layers; blistering usually occurs. The burn may be covered with soot or dirt, which needs removing, and blisters should be deroofed so that the base can be checked. Capillary refill can be tested by pressure from a sterile cotton bud. A 21 gauge needle is used to test sensation and bleeding; in superficial dermal burns, pain is felt normally and bleeding is brisk. Scalds tend to cause ‘superficial’ to ‘superficial dermal’ burns

• Deep dermal burns—these destroy all the epidermis and most of the dermis, leaving only the deepest skin adnexae, sweat glands and some hair follicles, all of which are scanty. Accurate depth estimation can be difficult. On needle testing, bleeding is delayed and only non-painful sensation is experienced

• Full thickness burns are insensate and do not bleed on needling

Principles of management of burns

First aid: The first priority at the scene is to stop the burning process. The heat source must be removed and any flames doused. Clothing is removed unless stuck to the burn, and active cooling employed to remove heat and arrest progression. Ideally this is achieved by immersing the burnt area in tepid water (~15°C) for 15–20 minutes. This can cause hypothermia, especially in children.

Analgesia: Burns are very painful, with pain being greatest in superficial burns. Pain relief is best achieved by cooling and covering burns in addition to analgesic drugs. In larger burns, opioids are given initially and NSAIDs later.

Dressings: Cling film (PVC) is ideal as an initial burn dressing. It is essentially sterile and forms a pliable, non-adherent, impermeable barrier which is transparent to allow inspection. It should be laid on rather than wrapped around and covered with a blanket to keep the wound warm. Burnt hands are enclosed in plastic bags. Prepacked cooling hydrogels, e.g. Burnshield®, are available for applying at the scene of the burn.

Where should burns be managed?: Very small or erythema-only burns can be managed in primary care but all other patients should be assessed and resuscitated in an emergency unit. Initial assessment then determines whether treatment can continue as an outpatient in a general hospital, whether admission is required or whether transfer to a specialist burns unit is needed. Patients with extensive burns involving more than 30% of body surface should be transferred to a specialist burns unit right after initial treatment and resuscitation. Facial burns should also be referred after covering with bland paraffin ointment (repeated every 1–4 hours to minimise crust). Other referral criteria are summarised in Box 17.3.

Management of extensive burns

Resuscitation and fluid management: Adults with 15% and children with 10% body surface burns lose sufficient fluid to be at risk of hypovolaemic shock. Fluid replacement depends on the area of the burn and the patient’s weight. Hypovolaemia in the presence of myoglobinaemia readily precipitates acute renal failure. Effective resuscitation maintains tissue perfusion in the zone of stasis, inhibiting depth progression. Most fluid is lost in the first 8–12 hours, during which there is a general shift of fluid from intravascular to interstitial. Substantial fluid losses continue for at least another 36 hours. Rapid boluses of fluid should not be given early on as raised intravascular hydrostatic pressure drives it rapidly out of the circulation.

Fluid requirements should be calculated from the time of injury, not the time of arrival in the emergency department. Colloids appear to offer no advantage over crystalloids and the volume required is estimated by referring to well-tried formulae such as that of Muir and Barclay shown in Figure 17.7, or the Parkland formula, Box 17.4. The Parkland formula has the advantage that it uses only crystalloids, it is easy to calculate and the rate can be adjusted by titrating against urine output.

Local management of the burns: All wounds should achieve epithelial cover within 3 weeks to minimise scarring. Partial thickness burns re-epithelialise spontaneously given proper care, but full thickness burns require excision and skin grafting. Fingers, eyelids, limb flexures and genitalia nearly always require primary grafting soon after injury. For optimal care, grafting should be performed within 5 days of injury and patients needing transfer to a burns unit should reach there within a maximum of 10 days.

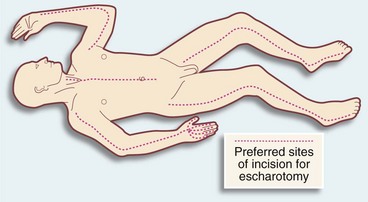

Deep circumferential burns of the limbs and thorax begin to contract early and may restrict blood flow and respiratory movements. If excision and grafting is not done early, and if these signs develop, escharotomy is performed, involving incision of the eschar longitudinally down to bleeding tissue (Fig. 17.8).

Inhalational injuries

Respiratory and systemic damage from inhalation of hot air, smoke and toxic gases (e.g. carbon monoxide or cyanides from burning upholstery) is a major cause of death and complications even if skin burns are insignificant (Box 17.5). The heat of inhaled gases is often sufficient to cause inflammatory oedema of the oral, nasal and laryngeal mucosa or even serious burns. Blackening by smoke or burnt skin around the nasal or oral cavities warns of inhalation injury. In addition, noxious gases can injure the lung parenchyma, resulting in pulmonary oedema, atelectasis and secondary pneumonias a day or two later.