CHAPTER 80 SOFT TISSUE INFECTIONS

Soft tissue infections occur frequently and account for approximately 48.3 in 1000 outpatient visits. The severity of these infections varies from trivial to life-threatening.

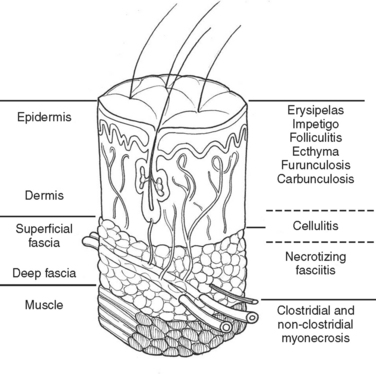

Much of our knowledge regarding the treatment of soft tissue infection has been based on the experience gained during military conflicts. For instance, hospital gangrene was described first by Joseph Jones, a Confederate surgeon during the Civil War. The treatment of battlefield infections has influenced civilian practice. This review will begin with a description of the anatomically more superficial infections and progress to the deeper, life-threatening infections (Figure 1).

DEEP INFECTION

In the medical literature, deep structure infection has masqueraded under a variety of pseudonyms. The term “necrotizing soft tissue infection” (NSTI)is used here. Table 1 lists a variety of terms that may appear in the medical literature to describe this infective process.

| Meleney’s synergistic gangrene | Hospital gangrene |

| Streptococcal gangrene | Fournier’s gangrene |

| Gas gangrene | Acute dermal gangrene |

| Suppurativa fasciitis | Necrotizing erysipelas |

| Phagedena | Phagedena gangrenosum |

| “Flesh-eating disease” | Necrotizing fasciitis |

| Clostridial cellulitis |

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Signs and symptoms of NSTI can be quite nonspecific (Table 2). Pain, erythema, and swelling of the affected area are most frequently present. This same constellation of symptoms may be seen in pathologic processes that have a much more benign course and respond effectively to antibiotic therapy alone. “Hard signs” of necrotizing infection include tense erythema, bullae, skin discoloration, and crepitus, pain out of proportion to examination, or anesthesia of the affected area. Unfortunately, many of these are late signs and indicate that the infective process is well established or they occur only in a small percentage of patients.

Signs of systemic toxicity may also be present. These may include pyrexia, tachycardia, hypotension, and organ dysfunction. The progression of symptoms may be rapid over the course of hours to days or more indolent over the course of days to weeks. The rate of progression of symptoms may be ameliorated by partial treatment. Some suggest classifying the disease by its clinical course. Fulminant disease presents in patients with acute onset and rapid progression over the course of hours with shock. Acute disease presents with large surface area involvement and over the course of days. Subacute disease presents for weeks and is usually localized. Differentiating this process from cellulitis or simple abscess can be a challenge. Clinically, failure to improve with appropriate antibiotics or worsening systemic toxicity portends this diagnosis (Table 3).

| Rapid progression: |

Laboratory data are equally nonspecific. Leukocytosis, hyponatremia, and elevated creatinine phosphokinase have been evaluated in clinical studies and may be markers of the disease. Wall et al. matched 21 patients with necrotizing fasciitis with controls and attempted to identify parameters that would distinguish the groups. White blood cell count (WBC) > 15.4 × 109/l, serum sodium (Na) less than 135 mmol/l, or both, were the best factors to distinguish necrotizing fasciitis from non-necrotizing fasciitis. The sensitivity was 90%, and the specificity was 76%. In this study, 40% of the patients with necrotizing fasciitis lacked “hard signs.” Wong and colleagues developed the Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) score. The score was developed retrospectively based on WBC, hemoglobin (Hgb), serum Na, C-reactive protein, creatinine, and glucose in patients with necrotizing fasciitis and patients with other severe soft tissue infections. A score of ≥6 had a positive predictive value of 92% and a negative predictive value of 96%. In a cohort of prospectively evaluated patients, the model was found to have a positive predictive value of 40% and a negative predictive value of 95%. Creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) elevation was found by one group to distinguish patients with group A streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis (GAS) from non–group A streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis. CPK elevations were >600 IU/l in the GAS group.

SURGICAL TREATMENT

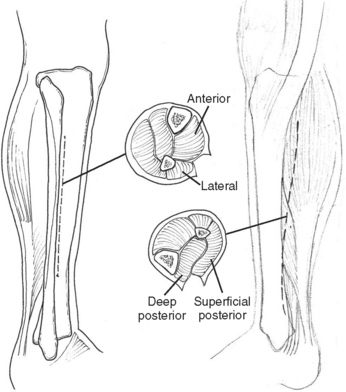

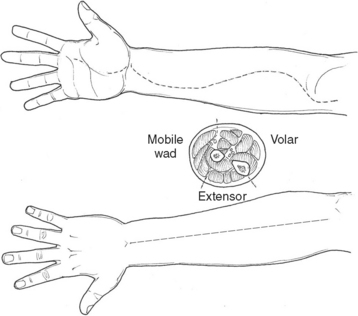

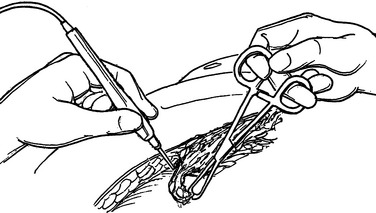

Necrotizing fasciitis is a surgical emergency. The mainstay of treatment is surgical debridement. These procedures can be quite deforming, requiring the removal of large amounts of skin, subcutaneous fat, fascia, and possibly muscle or bone. Explorations on the extremities are usually begun by making generous vertical incisions. When involvement is diffuse, fasciotomy incisions on the extremities are often a useful starting place. The dissection must extend down to the level of the deep fascia. The muscle should also be inspected to confirm its viability (Figure 2). Formal fasciotomies may be necessary in cases with very intense edema in order to prevent myonecrosis (Figure 3).

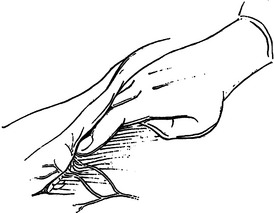

The integrity of the tissue plane between the subcutaneous fat or superficial fascia and the deep fascia is tested with either a finger or clamp (Figure 4). Lack of resistance to this probing is the hallmark of the diagnosis in early cases. “Dishwater pus” may be encountered as this plane is opened. In more advanced cases, frankly necrotic or purulent material is encountered. Cultures for stat Gram stain and aerobic and anaerobic cultures should be obtained. If the patient is immunosuppressed, cultures for Mycobacterium and fungus should also be sent. It is imperative to widely open all affected tissue planes and debride all obviously devitalized tissue (Figure 5).

When the presentation is more focal, incisions can be placed over the area of maximal skin abnormality and the incision extended as abnormalities of the deeper tissue are encountered. A colostomy may be helpful in cases with extensive perianal involvement to prevent ongoing stool contamination. Surgical feeding tube placement should be considered in critically ill patients or in patients with large surface area wounds that are likely to remain open for some time.

HYPERBARIC OXYGEN

Hyperbaric oxygen (HBO) is an adjunct to resuscitation, surgical debridement, and broad spectrum antibiotics. A variety of salutary affects have been attributed to HBO therapy (Table 4). There are no prospective randomized studies to scientifically validate the efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. There are a number of retrospective studies that seem to support its use in severe necrotizing infections. Several studies demonstrated decrease mortality in patients treated with HBO compared with historic controls. Other studies demonstrated improved preservation of tissue as evidenced by a decrease in the number of debridements to achieve control of the infection. Some studies, however, have questioned the efficacy of HBO. These studies showed no statistically significant difference in mortality between patients treated with HBO and those who received only surgical debridement. HBO therapy is not uniformly available throughout the country, so it is not an option for every patient who presents with this problem. When available, given the relatively high mortality and morbidity, use of this modality as an adjunct makes sense.

CONCLUSIONS

NSTI can occur under a variety of clinical conditions. It should be considered in postsurgical, post-traumatic wounds as well as in wounds from insect or animal bites. Differentiation from superficial infection is mandatory to assure appropriate surgical therapy is performed. Patients who fail to respond to appropriate medical therapy or who present with evidence of shock or organ dysfunction often harbor deeper infections. Patients with leukocytosis, hyponatremia, hyperglycemia, elevated creatinine, C-reactive protein, or CPK on laboratory evaluation should elicit an aggressive evaluation. This may include radiographic workup or surgical exploration. Progression of physical findings, including worsening edema, blistering, and crepitans or skin necrosis, mandates surgical exploration. Delays in treatment result in increased mortality and morbidity.

Bosshardt TL, Henderson VJ, Organ CH. Necrotizing soft-tissue infections. Arch Surg. 1996;131:846-854.

Brook I, Fraxier EH. Clinical and microbiological features of necrotizing fasciitis. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2382-2387.

Callahan TE, Schecter WP, Horn JK. Necrotizing soft tissue infection masquerading as cutaneous abscess following illicit drug injection. Arch Surg. 1998;133:812-818.

Elliott DC, Kufera FA, Meyers RA. Necrotizing soft tissue infections: risk factors for mortality and strategies for management. Ann Surg. 1996;224:672-683.

Simonart T, Nakafusa J, Narisawa Y. The importance of serum creatinine phosphokinase level in the early diagnosis and microbiological evaluation of necrotizing fasciitis. Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:687-690.

Tang WM, Ho PL, Fung KK, Yuen KY, Leong JC. Necrotizing fasciitis of a limb. J Bone Joint Surg. 2001;83:709-714.

Theis FC, Rietveld J, Danesh-Clough T. Severe necrotising soft tissue infections in orthopaedic surgery. J Orthop Surg. 2002;10:108-113.

Wall DB, de Virgilio C, Black S, Klein S. Objective criteria may assist in distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from nonnecrotizing soft tissue infection. Am J Surg. 2000;179:17-21.

Wall DB, Klein SR, Black S, de Virgilio C. A simple model to help distinguish necrotizing fasciitis for nonnecrotizing soft tissue infection. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;191:227-300.

Wilkinson D, Doolette D. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment and survival from necrotizing soft tissue infections. Arch Surg. 2004;139:1339-1345.

Wong CH, Chang HC, Pasupathy S, Khin LW, Tan JL, Low CO. Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85A:1454-1460.

Wong CH, Khin LW, Heng KS, Tan KC, Low CO. The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1535-1541.

Wu W, Scannell C, Lieber MJ, Huang W. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy: current status in the management of severe nonclostridial necrotizing soft tissue infections. Curr Treat Opin Infect Dis. 2001;3:217-225.