CHAPTER 54 Sociocultural Evidence and Whiplash

INTRODUCTION

Approximately one million diagnoses of whiplash-associated disorders (WAD) are made each year in the United States alone. The health and economic burden to society is substantial and made worse by our inability in most cases to identify a specific structural cause of ongoing complaints of pain and disability. In 1995, the Quebec Task Force (QTF) on Whiplash-Associated Disorders (WAD) did, however, make an important contribution by providing a grade 0 to grade 4 classification protocol based on the available literature.1 This classification system has been widely used both by clinicians and in research studies.2,3 The classification system is convenient because grades are primarily based on physical signs and symptoms. A patient with no symptoms is classified as grade 0. The more severe cases are grade 3, in which patient symptoms associated with neurological signs caused by a specific structural diagnosis, e.g. disc herniation causing nerve root compression, and grade 4, in which patients have symptoms caused by cervical fracture and/or dislocation. Ninety percent of ‘whiplash injury claims’ are, however, classified as grade 1 and grade 2.4 Grade 1 WAD classifies a patient who reports neck pain, stiffness, or tenderness with no other physical signs. Grade 2 WAD defines a patient who reports neck pain, stiffness, or tenderness and signs including reduced range of motion and point tenderness. The QTF classification of WAD is shown in Table 54.1.

Table 54.1 Clinical Interpretation of the Quebec Task Force Whiplash-Associated Disorders (WAD) Classification Scheme

| Grade | Injury (example) and Symptoms | Signs |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Possible muscle sprain | Normal range of motion |

| Spinal symptoms included neck stiffness, pain, or tenderness only |

Notes:

Although a structural diagnosis is often conjectural or unknown, up to 50% of whiplash victims with WAD 1 or 2 report persistent pain for more than 6 months after their collision.5–7 Despite the availability of modern imaging techniques and despite the increasing use of interventional diagnostic and therapeutic procedures, the incidence of chronic pain following whiplash injuries continues to rise. In this chapter, we de-emphasize the structural approach and instead discuss the cultural disparities of chronic whiplash, and review literature that suggests chronic whiplash pain can be better explained by patients expectations and by symptom amplification. We will argue that research efforts should be focused on reversal or prevention of the psychocultural phenomena that contribute to chronic pain following whiplash injuries. We emphasize diagnosis and treatment based on evidence and not ever-increasing use of unproven invasive interventions.

THE EVIDENCE ON CULTURAL DISPARITIES IN WHIPLASH

Some cultures are Petri dishes for chronic whiplash and some are not. Every study reported from Canada,5,6 Sweden,4,8 the United States,9 England,10,11 Ireland,12 and Norway13 on the outcome of patients classified into WAD grade 1 or 2 indicate a high prevalence of chronic pain. In these studies WAD 3 and 4 are either excluded or represent only a small minority of subjects and the vast majority of chronic whiplash complaints are classified as WAD 1 or 2. Even though patient samples were captured as ‘acute cases’ using different methods, such as insurance claims databases, advertising to primary care clinics, or from emergency departments, the reported prevalence of chronic pain are similar. No matter the source or whether questionnaires were or were not used, all studies from these Western countries confirm the high incidence of chronic pain after acute whiplash. On the other hand, using similar methodologies on the same WAD 1 and 2 classified patients, researchers conducting studies in Lithuania, Germany, and Greece report a very different incidence of chronic pain following whiplash injuries.

Lithuania

Lithuania is a country in which there is no or little awareness or experience among the general population that a whiplash injury is a reason for chronic pain and disability. Collision victims do not often seek extended medical attention, and the possibilities for secondary gains are minimal. In a controlled, historical inception cohort study published in 1996,14 none of the 202 subjects involved in a rear-end car collision 1–3 years earlier had persistent and disabling complaints that could conceivably be linked to the collision. Both collision victims and controls had the same statistical occurrence of symptoms including neck pain, headache, and subjective cognitive dysfunction. In a later prospective, controlled inception cohort study,15 47% of 210 victims of rear-end car collisions consecutively identified from the daily records of the traffic police had initial pain. The symptoms disappeared in most cases after a few days. No subject reported collision-induced pain later than 3 weeks, compared to Canada where a mere 50% were symptom free by 6 months.5 After 1 year, there were no significant differences between the collision victim group and the control group in frequency or intensity of neck pain and headache. In a historical cohort study,14 31 collision victims recalled having had acute or subacute neck pain. In most cases symptoms lasted less than 1 week and only two subjects had neck pain for more than 1 month. Due to recall problems, the true incidence of collision victims with acute symptoms such as neck pain and/or headache was unknown. However, the prospective inception study provides a 95% confidence limit for the true prevalence of acute, post-collision symptoms as 40–54%.15 Because none of the 180 subjects in both Lithuanian studies was reported to have persistent and disabling symptoms due to the collision, the possibility of chronic pain was less than one in 60 (p<0.05). Thus, these studies evaluated either alone or together have sufficient power to reject the approximately 50% estimates5 of the development of the so-called chronic whiplash syndrome in other countries.

Greece

Chronic whiplash syndrome may also be rare in Greece. In 130 consecutive collision victims suffering acute whiplash symptoms, 91% recovered in 4 weeks. The remainder had substantial improvement and recovered within 3 months.16 Extending their series to 180 patients confirmed this results, not only for recovery from neck pain, but from the other symptoms commonly reported as part of the acute injury syndrome.17

Germany

Germany also may have a low incidence of chronic whiplash pain. In a study of physical therapy treatment, by 6 weeks the active treatment group and control (healthy) groups were equal in their symptom reporting. Even the group given only a collar for 3 weeks and no other therapy recovered by 12 weeks. In this study the acute whiplash injury patient had no greater risk of reporting chronic symptoms than found in the general, uninjured population.18 A prospective outcome study by Keidel et al. of 103 subjects in another locale in Germany found the same good prognosis: recovery often within 3 weeks, and virtually all within 6 weeks.19 Similar, rapid recoveries have been found in other parts of Germany.20

Symptom expectation

The differences between outcomes in these three countries cannot be ascribed to methodological issues, since methodological issues do not prevent researchers in countries such as Canada or Sweden from showing the existence of a high frequency of chronic pain. The diagnosis of a WAD case is the same in Sweden, Canada, or Lithuania – those who report symptoms after a collision are labeled as WAD – and the diagnosis of WAD 1 or 2 has no supporting objective manifestations or it would be classified as grade 3 or 4. The vast differences in outcomes cannot be simply ascribed to different medical systems, since Germany, Greece, and Lithuania also have different systems, but show similar outcomes. There is no evidence for the existence of cultural stoicism. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Lithuania or Germany report the same symptoms and disabilities as those in North America.21,22 If cultural stoicism caused Lithuanians and Germans to underreport chronic pain, it should do so for chronic pain from rheumatoid arthritis. There must instead be a common factor amongst Lithuanians, Germans, and Greeks that differs from, say, Canadian or those from the United States. One such factor may be symptom expectation. Ferrari et al. have examined levels of expectation for outcomes after acute neck sprain in Canadians, Lithuanians, Greeks, and Germans.23–25 The studies showed that the responses of the Canadian, Lithuanian, German, and Greek subjects in their expectation of chronic disability due to rheumatoid arthritis were remarkably similar. The acute ‘whiplash’ symptoms anticipated by all these groups are also very similar, but there is a markedly different expectation of the duration of these common ‘whiplash’ symptoms. Canadians commonly expect certain symptoms to be chronic, while Lithuanians, Greeks, and Germans do not. This data is consistent with the hypothesis that the chronic whiplash syndrome is in many cases culturally conditioned illness, and that symptom expectation may be an important factor that accounts for some of the variance between the ‘Whiplash Cultures,’ where the chronic whiplash syndrome is epidemic in proportion (e.g. North America, Scandinavia), and ‘non-Whiplash Cultures’ such as Lithuania, Greece, and Germany, where the acute whiplash injury is common, but the outcome benign, recovery being measured in days to weeks.

Thus, we should be focusing on why a particular whiplash patient has brought themselves for treatment and what factors may be making their pain more severe, and their coping less effective, before we immediately assume that the answer lies in biomechanical explanations. Besides symptom expectation, research suggests we need to consider many other factors, including what we as clinicians do or fail to do in the assessment and management of acute whiplash patients.

THE EVIDENCE ON PATIENT ASSESSMENT

The literature on history-taking and physical examination of the whiplash patient usually focuses on the prognostic factors for WAD grades 1 and 2. Because of small patient samples done in a single geographical location, individual studies may not be helpful for identifying reliable prognostic factors and may not apply to other patient populations. In fact, as reviewed by Quebec Task Force1 there are only a few studies focusing on prognosis and outcome in WAD 1 and 2. The largest study with less selection bias, and greater breadth and detail of data concerning collision parameters, demographics, and symptoms as predictors of outcome is the Saskatchewan-based cohort by Cassidy et al.26–28 While the study by Cassidy et al.26 is controversial because the influence of the tort or no-fault system in Saskatchewan, there can be little doubt that the size of the population studied, and the extensive data gathering concerning individual subjects, makes this the most powerful study of whiplash prognosis.

The study by Cassidy and all other pre-2001 outcome studies were analyzed by Cote et al. specifically to identify prognostic factors.28 The analyzed studies consistently showed the following postinjury factors were associated with poor outcome: age greater than 40; female gender; more intense baseline neck or back pain; more intense baseline headache; the presence of baseline radicular signs and symptoms; and the presence of depressive or other significant emotional distress symptoms within the early weeks after injury. These factors were prognostic in both the tort and no-fault system as opposed to the effect the tort system had on prognosis.26 More important were the factors that did not predict outcome. (See Table 54.2 for a summary.) Though pre-1995 studies had suggested that factors such as head position at time of collision, initial X-ray findings, the direction of impact, and amount of vehicle damage were prognostic, subsequent, larger, and better designed studies have not affirmed these findings, and have even contradicted them. Furthermore, in the Saskatchewan study the location of impact, seat belt or head restraint use or position of head restraint, the general health before the collision, previous whiplash injury, or symptoms before collision were of no prognostic value. In fact, the value of various prognostic factors are based on pre-1995 studies that were both small groups of highly selected subjects with inadequate data collection.

| FACTORS REPEATEDLY SHOWN TO BE ASSOCIATED WITH A WORSE OUTCOME | |

| Age greater than 40 | |

| Female gender | |

| More intense baseline neck or back pain | |

| More intense baseline headache | |

| The presence of baseline radicular signs and symptoms | |

| The presence of depressive or other significant emotional distress symptoms within the early weeks | |

| NOT ASSOCIATED WITH A WORSE OUTCOME IN POWERFUL STUDIES | |

| Direction of collision (rear, frontal or side) | |

| Seat belt or head restraint use | |

| Position of head restraint | |

| General health before the collision | |

| Previous whiplash injury | |

| Previous symptoms before collision | |

| LACK OF SUFFICIENT EVIDENCE TO CONFIRM OR DENY ROLE | |

| Marital status | |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| Level of education | |

| Number of dependants | |

| Level of income | |

| Initial X-ray findings of osteoarthritis (disc degeneration) | |

Using a best-evidence approach, beside the obvious factors age and gender, the most relevant prognostic factors are the intensity initial symptoms and emotional distress. Merely noting how intensely the patient describes their symptoms and their level of distress will best identify the highest risk for delayed recovery. Although the physical examination obviously assists in ruling out other injuries, and classifying the WAD grade, there is little evidence that examination itself will identify factors that affect prognosis. Similar to the chronic low back pain patient, ‘nonorganic’ pain behaviors may predict failure to respond to almost any medical therapy, including medications, exercise, and surgery, if they are considering these therapies in patients with ‘pain behaviors.’29

These ‘behavioral’ signs are otherwise labeled as ‘nonorganic’ or Waddell’s signs and although these signs were described in low back patients, one might assume that the same signs would be important in pain in other areas. Waddell’s signs include grimacing, leaping when touched, inability to sit through the interview, marked superficial tenderness, back pain with axial skull loading, back pain with mild hip rotation, significant differences in straight leg raise when distracted, nondermatomal sensory loss, and jerky, give-way weakness. One can appreciate comparable findings in neck pain, including a neck that becomes rigid when the patient is specifically told they are having their neck range tested (versus their apparent range of motion when ‘unawares’), superficial tenderness, nondermatomal sensory loss, neck pain with minor movements of the shoulder joint, and jerky, give-way weakness of the arm.30

The presence of least three of these ‘behavioral’ signs has been found in studies to be a significant predictor of a poor response to medical or surgical therapy, and to correlate well with psychological distress.29 These signs are relevant: to dismiss or ignore them is to miss an opportunity for early intervention. Identifying Waddell’s signs may allow the physician to prescribe more effective therapy leading to improved outcome in chronic low back pain.31 When a patient has these signs, if behavioral (or cognitive) psychotherapy is the mainstay of treatment, the presence of Waddell’s signs are no longer predictive of a poor outcome.31 Since about 50% of whiplash patients have low back pain, the relevance seems likely, but has not been specifically studied in whiplash patients. There is no reason, however, why whiplash patients with pain behaviors should have any better prognosis, and the best evidence from the chronic pain literature suggests physicians should identify these patients early in the course of their disorder. There are, however, important caveats. First, while they may obviously suggest a malingerer, who wrongly thinks to be making a more convincing impression on the physician, these signs are found even in individuals with known structural pathology. Their presence reflects not the absence of an organic cause (thus, ‘behavioral’ signs is a better term than ‘nonorganic’), but rather that the severity of symptoms, disability, and behavior cannot be explained on structural pathology alone. Thus, anxiety, depression, and a tendency to focus on symptoms will affect the behavior during examination in ways that physical pathology will not. Furthermore, their significance has not been formally evaluated in non-English cultures. Table 54.3 summarizes the ‘red flags’ that can be gathered from the history and physical examination.

Table 54.3 The ‘Red Flags’ that Indicate a Poor Prognosis in Patients with WAD 1 or 2

| Age greater than 40 |

| High initial intensity of headache, neck or back pain |

| High emotional distress |

| Presence of depressive symptoms |

| Presence of radicular symptoms |

| Pain behaviors and other behavioral (Waddell’s) signs present |

The presence of these flags suggests the physician may wish to have closer follow-up and/or involve specialist referral at an early stage.

Radiological Assessment

Many physicians order a cervical spine X-ray to reassure the patient and themselves that the rare possibility of fracture in an apparently otherwise ‘typical’ soft tissue injury has been ruled out. This is a step in WAD grading. The Quebec Task Force suggested that an X-ray was not required for WAD grade 1. Even though most X-rays will be negative, if physical findings are present an X-ray is recommended to exclude fracture. Hoffman et al.32 studied over 30 000 cases of blunt nonpenetrating trauma to the neck caused mostly by motor vehicle collisions. They developed a decision instrument which requires patients to meet the following five criteria for a low probability of significant structural injury: no midline cervical tenderness; no focal neurologic deficit; normal alertness; no intoxication; and other painful injury that would distract the patient from noticing the severity of their neck tenderness. With this decision rule, eight of 818 patients with bony injury were missed, and only two of these eight were considered to have clinically significant injuries that might have a potential for complications. Another prospective study by Stiell et al.33 in nine Canadian emergency departments evaluated decision rules for X-rays in patients with trauma. None of 1812 patients in simple rear-end collisions were found to have evidence on X-ray of cervical spine injury. But despite the apparent usefulness of criteria rules, concerns have been raised that to miss even two cases of relevant injury in 800 is unacceptable in our current medicolegal environment. Thus, many physicians will order neck X-rays. Besides the increased cost, there is perhaps a bigger problem of wrongfully elevating benign degenerative X-ray finding to pathological significance.

Many physicians continue to attribute chronic neck pain syndrome secondary to degenerative disc disease, although once studies are controlled for age, there is no independent correlation between symptoms and disc findings, regardless whether the findings are detected with X-ray, discography, CT scan, or MRI.34 Even disc protrusions without nerve root or spinal cord compression, spinal stenosis, and small degrees of vertebral subluxation had no predictive value for the presence of neck pain, and are just as frequently found in asymptomatic subjects. On the other hand, where there is a good clinical reason to suspect a specific root lesion based on the neurological examination, a CT or MRI may provide necessary preoperative anatomical confirmation. Telling patients that their pain arises from degenerative change or osteoarthritis of the spine is not evidence based and may give the patient the impression that they have a chronic, unrelenting, and likely untreatable cause of pain. Furthermore, this belief could lead to withdrawing from activities, developing anxiety, and seeking many different forms of ‘cure.’

In the patient with neurologic physical signs, an MRI or CT scan should be obtained to help confirm or refute a WAD grade 3 and to identify which neurologic structures are involved. However, the MRI or other imaging studies are only important in identifying fractures, dislocations, or neurologic compromise and there is no evidence that other ‘degenerative’ findings will identify a cause of pain or physical findings. Minor degrees of forward angulation of the cervical spine or kyphosis, ‘straightening of the lordosis’ or ‘disc disease,’ or ‘osteoarthritis’ are found in asymptomatic controls as frequently as in acute whiplash injury patients.33 There is little evidence that having an abnormal X-ray at the time of the acute injury affects the outcome.34 Patients are often told that their X-ray shows many ‘abnormalities’ without the explanation that these findings are either normal or age-related findings.34 Thus, in the vast majority of whiplash claimants, the various, commonly identified radiological abnormalities do not correlate with symptoms and merely represent the background prevalence of such findings in the general population. Patients with WAD 1 or 2 should, from an evidence-based approach, be reassured that they would have their neck pain regardless of osteoarthritis on their X-rays, and that they would (and did) have degenerative changes (‘arthritis of the spine’), even without pain.

THE EVIDENCE ON TREATMENT OF ACUTE WAD

Although there are few studies allowing scientific evaluation of treatment of whiplash patients, there are several published literature reviews. These studies include Quebec Task Force 1995,1 Kjellman et al. 1996,35 and Peeters et al. 2001.36 The survey by Kjellman et al. includes non-English language scientific publications, and combines studies of therapy for both traumatic and nontraumatic neck pain. In addition, although the surveys by the Quebec Task Force and Peeters et al. were designed to study ‘whiplash therapy’ both included reviews of studies with mixed populations of neck pain patients.

From available data, it is clear that therapy prescriptions including an active exercise are superior to those which rely on passive therapy modalities such as ultrasound, manual therapy, massage, heat, TENS, and laser. Controlled studies have not validated electromagnetic therapy, traction, collars, TENS, ultrasound, spray and stretch, local corticosteroid injections, trigger point injections, and laser therapy.1 The Quebec Task Force found the effectiveness of manipulation/chiropractic therapy in acute neck pain to be equivocal and noted that the study design either reflected significantly different baseline characteristics in cohorts, or some studies failed to find a therapeutic effect. Because of the mixed prescriptions of multiple passive modalities versus various exercises in some studies, it is not clear whether exercise is better because it is effective, or because passive therapy is harmful, or both. It is also not clear what aspect or type of exercise therapy is more effective.

Peeters et al.36 recently summarized the few acute neck treatment studies published since 1995. These studies again indicate that exercise therapies are superior to passive modalities and that ‘rest makes rusty.’ One of the most impressive studies in acute whiplash patients was by Borchgrevink et al.13 in Norway. The authors compared giving or not giving the therapeutic advice to ‘act as usual’ in a randomized group of 241 neck pain patients whose onset of pain was within 24 hours of a motor vehicle collision, and who had no signs or radiological findings to suggest neurological injury or fracture. All patients received instructions for self-training of the neck and a 5-day prescription for a nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug. One group was instructed to act as usual and received no sick leave or collar. Patients in the immobilization group received 14 days of sick leave and a soft collar. At 6 months after the collision, the ‘act as usual’ group had a better outcome in several variables including pain, concentration, and memory. The study is impressive because the difference between the two groups was simply advice coupled with no sick leave and no collar, versus both sick leave and a collar. Although the beneficial effect of advice versus the adverse effect of wearing a collar could not be determined, the outcome in the ‘act as usual’ group was better than is typically reported in most studies, suggesting some definite benefit to that advice. Such an effect illustrates the importance of modifying patient behavior as a method to preventing the transition from acute to chronic neck pain.

While there is a confirmed relationship between various measures of postural changes and chronic spinal pain, the exact role of postural changes in the transition from acute to chronic pain is unknown. McKinney et al. found a beneficial effect of postural exercises and the use of a lumbar roll. The comparison group was, however, using passive physical therapy modalities only and it is therefore not clear whether the treatment was beneficial or the control group had a deleterious outcome as a result of passive therapy. Nevertheless, the head-forward posture has been shown to be corrected by neck retractions,37 and lumbar rolls have been tested and found effective for low back pain,38 and were included in the active therapy studied by McKinney et al.12 Studies have shown collar use will delay recovery even in subjects with an otherwise expected good outcome.18,20 Thus, the advice to maintain usual activity, to exercise, and to use a lumbar roll is superior to the myriad of other therapies that are otherwise passive and may in fact be detrimental.

THE EVIDENCE ON SYMPTOM AMPLIFICATION

Patient symptoms may be amplified by variables independent of injury or disease and some variables can be prevented and some aggravated by the treating physician.38,39 A patient’s emotional state determines how one perceives minor, day-to-day symptoms from life’s activities, including occupational sources. Patients have been shown, for example, to recall symptoms in a way that matches their current emotional state. If one asks someone who is currently distressed about headaches, the person will recall many more severe headaches episodes than when in a good mood. Studies show that the direction of the effect IS NOT that symptoms significantly affect one’s mood, but rather one’s mood affects symptoms and symptom recall.39,40 A patient will recall many symptoms during a period of emotional or psychological distress, and will underreport or have poor recall of symptoms in the more remote past when less distressed.40 In addition, anxiety and depression facilitate recall of unpleasant past events, negative experiences and, in particular, previous illnesses. For example, Croyle et al. induced positive or unpleasant mood among a group of subjects who were then asked to recall their prior symptoms in the last 30 days.41 Those who underwent an unpleasant mood induction recalled more symptoms than individuals who underwent a positive mood induction. Similarly, Cohen et al. showed that in otherwise healthy subjects who underwent exposure to a respiratory virus to induce illness, a higher psychological stress assessed before the viral challenge was associated with greater symptom scores in response to infection.42

Mood affects the perception of symptoms and the appraisal of one’s health.41 A negative mood makes illness-related memories more accessible and induces a poorer assessment of one’s overall state of health. It follows that a negative mood makes collision-related memories more accessible and leads a person to focus on symptoms that they are told are sequelae of the collision. Michelotti et al.43 further demonstrated that normal subjects, when in states of natural stress, have altered muscle function and tenderness about the jaw, a common problem in whiplash patients. Yet, these subjects suffered no injury and recovered as the psychological/emotional distress levels dropped. Similarly, Castro et al. were able to reproduce in a laboratory setting the acute whiplash syndrome in 20% of subjects who were falsely led to believe they had experienced a true motor vehicle collision.44 Despite the lack of any biomechanical forces to cause injury, the symptoms evoked were seemingly genuine in this setting, and their development was predicted by pre-experiment psychological measures of somatic focus and tendencies towards anxiety.

Second, as Barsky reveals, what we believe to be the cause of our symptoms affects how severely we perceive those symptoms. Studies show that patients who believe they are injured will have an underestimation of symptoms in the period before the patients believe they were injured. Thus, it has been shown patients with whiplash underestimate their pre-injury history of neck symptoms.45

Finally, the close attention to symptoms will affect symptoms. Kasch et al.46 showed that patients with ankle sprains, when asked through questionnaires and repeated examinations to pay close attention to symptoms such as headache, neck pain, and back pain, will become just like whiplash patients in 3 months. They will report the same symptoms and even the same restricted range of neck motion even though ankle sprain patients did not begin with spinal pain and even though 100% of the ankle sprain pain resolved within 6 months. Could these subjects be amplifying life’s background noise of symptoms? The study reaffirms the prognosis for ankle sprain, but perhaps the reason ankle sprains are not a long-term socioeconomic patient disability is that even in United States most ankle sprains are supposed to cause acute pain but patients and physicians alike do not accept an ankle sprain as a cause or reason for chronic pain and disability. Worry and fear of long-term pain is aggravated by friends and physicians agonizing over the chronic nature of whiplash injury. Ankle sprains, on the other hand, are considered a benign self-limiting process. Whatever the sources of WAD symptoms, the evidence suggests that patients symptoms will be aggravated in an environment that both promotes the seriousness of the symptoms and encourages the patient to focus on his or her symptoms.

THE EVIDENCE ON ACTIVE VERSUS PASSIVE COPING

Research by Carroll defines both active and passive coping (Table 54.4).47 Active coping refers to those coping strategies in which the patient takes responsibility for pain management and include attempts to control the pain or to function in spite of pain. Passive coping refers to strategies in which patients give the responsibility for pain management to an outside source or allow other areas of life to be adversely affected by pain. Passive coping is generally found to be associated with increased severity of depression, higher levels of activity limitation, and helplessness. Active coping has been found to be associated with less severe depression, increased activity level, and less functional impairment, but to be unrelated to pain severity. It is intuitively apparent that higher pain levels will stress any coping style, all the more so if the coping mechanisms are limited. Many patients use combinations of active and passive coping, but for any pain level, the higher the passive coping usage, the worse the outcome.

Table 54.4 Markers of Active and Passive Coping Styles for Pain

| ACTIVE COPING | |

| Engaging in physical exercise or physical therapy | |

| Staying busy or active | |

| Clearing your mind of bothersome thoughts or worries | |

| Participating in leisure activities (such as hobbies, sewing, stamp collecting, etc.) | |

| Distracting your attention from the pain (recognizing you have pain, but putting your mind on something else) | |

| PASSIVE COPING | |

| Saying to yourself, ‘I wish my doctor would prescribe better pain medication for me’ | |

| Thinking, ‘This pain is wearing me down’ | |

| Talking to others about how much your pain hurts | |

| Restricting or canceling your social activities | |

| Thinking ‘I can’t do anything to lessen this pain’ | |

| Focusing on where the pain is and how much it hurts | |

Regardless of levels of active coping, Carroll et al.47 further showed that the development of disabling neck, low back pain, or both was strongly associated with the high use of passive coping strategies. Even if a person stays busy or active, and engages in physical exercise, the concomitant tendency to hold passive strategies, such as relying heavily on pain medications, frequently focusing on and discussing their pain with others, and canceling social activities, negates the beneficial effects of the active coping. Passive coping is hazardous to the outcome. Recent research with whiplash patients confirms the relevance of coping styles to recovery.48

ADVICE FOR THE ACUTE WHIPLASH PATIENT

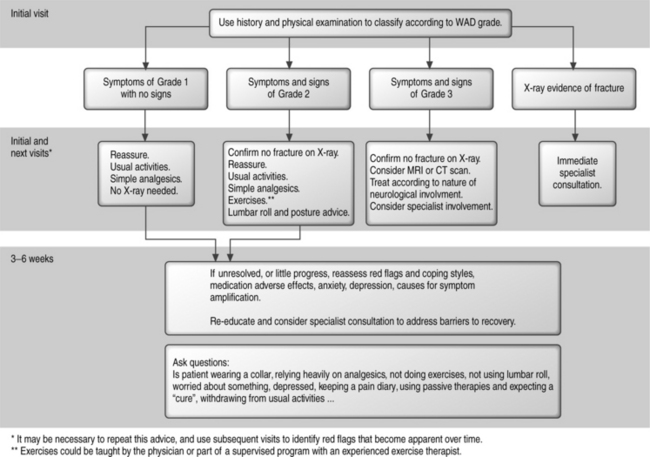

Physicians should be truthful with their patients. Physicians can give advice based on their own convictions and their own clinical experience but they should also know and adhere to the evidence-based literature. The following is the algorithmic approach proposed by the authors, based on the literature and their own convictions. Based on the literature, the appropriate treatment for WAD 1 and 2 is shown in Figure 54.1. The following is a summary of the advice that may be given to patients with grade 1 or 2 WAD, based on the literature and on the authors’ personal convictions.

1 Spitzer WO, Skovron ML, Salmi LR, et al. Scientific monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders. Spine. 1995;20(Suppl 8):1S-73S.

2 Hartling L, Brison RJ, Ardern C, et al. Prognostic value of the Quebec Classification of Whiplash-Associated Disorders. Spine. 2001;26:36-41.

3 Versteegen GJ, van Es FD, Kingma J, et al. Applying the Quebec Task Force criteria as a frame of reference for studies of whiplash injuries. Injury. 2001;32:185-193.

4 Holm L, Cassidy JD, Sjogren Y, et al. Impairment and work disability due to whiplash injury following traffic collisions. Scand J Public Health. 1999;2:116-123.

5 Cassidy JD, Carroll L, Cote P, et al. Effect of eliminating compensation for pain and suffering on the outcome of insurance claims for whiplash injury. N Eng J Med. 2000;342:1179-1186.

6 Brison RJ, Hartling L, Pickett W. A prospective study of acceleration–extension injuries following rear-end motor vehicle collisions. J Musculoskeletal Pain. 2000;8:97-113.

7 Suissa S, Harder S, Veilleux M. The relation between initial symptoms and signs and the prognosis of whiplash. Eur Spine J. 2001;10:44-49.

8 Hildingsson C, Toolanen G. Outcome after soft-tissue injury of the cervical spine. Acta Orthop Scand. 1990;61:357-359.

9 Gennis P, Miller L, Gallagher EJ, et al. The effect of soft cervical collars on persistent neck pain in patients with whiplash injury. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:568-573.

10 Gargan MF, Bannister GC. The rate of recovery following whiplash injury. Eur Spine J. 1994;3:162-164.

11 Mayou R, Bryant B. Outcome of ‘whiplash’ neck injury. Injury. 1996;27:617-623.

12 McKinney LA. Early mobilisation and outcome in acute sprains of the neck. Br Med J. 1989;299:1006-1008.

13 Borchgrevink GE, Kaasa A, McDonagh D, et al. Acute treatment of whiplash neck sprain injuries. A randomised trial of treatment during the first 14 days following car accident. Spine. 1998;23:25-31.

14 Schrader H, Obelieniene D, Bovim G, et al. Natural evolution of late whiplash syndrome outside the medicolegal context. Lancet. 1996;347:1207-1211.

15 Obelieniene D, Schrader H, Bovim G, et al. Pain after whiplash – a prospective controlled inception cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:279-283.

16 Partheni M, Miliaris G, Constantayannis C, et al. Whiplash injury [letter]. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:1206-1207.

17 Partheni M, Constantoyannis C, Ferrari R, et al. A prospective cohort study of the outcome of acute whiplash injury in Greece. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2000;18:67-70.

18 Bonk A, Ferrari R, Giebel GD, et al. A prospective randomized, controlled outcome study of two trials of therapy for whiplash injury. J Musculoskeletal Pain. 2000;8:123-132.

19 Keidel M, Baume B, Ludecke C, et al. Prospective analysis of acute sequelae following whiplash injury. World Congress on Whiplash-Associated Disorders; February 7–11, 1999; Vancouver, Canada.

20 Schnabel M, Ferrari R, Vassiliou T, et al. A randomized, controlled outcome study of active mobilization versus collar therapy for whiplash injury. Emerg Med J. 2004;21:306-310.

21 Dadoniene J, Uhlig T, Stropuviene S, et al. Disease activity and health status in rheumatoid arthritis: a case-control comparison between Norway and Lithuania. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:231-235.

22 Zink A, Braun J, Listing J, et al. Disability and handicap in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis – results from the German rheumatological database. German Collaborative Arthritis Centers. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:613-622.

23 Ferrari R, Obelieniene D, Russell AS, et al. Laypersons’ expectation of the sequelae of whiplash injury. A cross-cultural comparative study between Canada and Lithuania. Med Sci Mon. 2002;11:728-734.

24 Ferrari R, Constantoyannis C, Papadakis N. Laypersons’ expectation of the sequelae of whiplash injury: a cross-cultural comparative study between Canada and Greece. Med Sci Mon. 2003;9:CR120-CR124.

25 Ferrari R, Lang C. A cross-cultural comparison between Canada and Germany of symptom expectation for whiplash injury. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18:92-97.

26 Cassidy JD, Carroll L, Cote P, et al. Low back pain after traffic collisions: a population-based cohort study. Spine. 2003;28:1002-1009.

27 Cote P, Hogg-Johnson S, Cassidy JD, et al. The association between neck pain intensity, physical functioning, depressive symptomatology and time-to-claim-closure after whiplash. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:275-286.

28 Cote P, Cassidy JD, Carroll L, et al. A systematic review of the prognosis of acute whiplash and a new conceptual framework to synthesize the literature. Spine. 2001;26:E445-E458.

29 Waddell G, Pilowsky I, Bond MR. Clinical assessment and interpretation of abnormal illness behaviour in low back pain. Pain. 1989;39:41-53.

30 Sobel JB, Sollenberger P, Robinson R, et al. Cervical nonorganic signs: a new clinical tool to assess abnormal illness behavior in neck pain patients: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:170-175.

31 Ferrari R. Comment on Polatin et al., Predictive value of Waddell signs [letter]. Spine. 1999;24:306.

32 Hoffman JR, Mower WR, Wolfson AB, et al. Validity of a set of clinical criteria to rule out injury to the cervical spine in patients with blunt trauma, for The National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:94-99.

33 Stiell IG, Clement CM, McKnight RD, et al. The Canadian c-spine rule versus the NEXUS low-risk criteria in patients with trauma. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2510-2518.

34 Ferrari R. The whiplash encyclopedia. The facts and myths of whiplash. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers, 1999;25-37.

35 Kjellman GV, Skargren EI, Öberg BE. A critical analysis of randomised clinical trials on neck pain and treatment efficacy. A review of the literature. Scand J Rehab Med. 1999;31:139-152.

36 Peeters GG, Verhagen AP, de Bie RA, et al. The efficacy of conservative treatment in patients with whiplash injury: a systematic review of clinical trials. Spine. 2001;26:E64-E73.

37 Pearson ND, Walmsley RP. Trial into the effects of repeated neck retractions in normal subjects. Spine. 1995;20:1245-1250.

38 Williams MM, Hawley JA, McKenzie RA, et al. A comparison of the effects of two sitting postures on back and referred pain. Spine. 1991;16:1185-1191.

39 Barksy AJ. Forgetting, fabricating, and telescoping. The instability of the medical history. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:981-984.

40 Simon GE, Gureje O. Stability of somatization disorder and somatization symptoms among primary care patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:90-95.

41 Croyle RT, Uretsky MB. Effects of mood on self-appraisal of health status. Health Psychol. 1987;6:239-253.

42 Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Skoner DP. Psychological stress, cytokine production, and severity of upper respiratory illness. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:175-180.

43 Michelotti A, Farella M, Tedesco A, et al. Changes in pressure–pain thresholds of the jaw muscles during a natural stressful condition in a group of symptom-free subjects. J Orofacial Pain. 2000;14:279-285.

44 Castro WH, Meyer SJ, Becke ME, et al. No stress – no whiplash? Prevalence of ‘whiplash’ symptoms following exposure to a placebo rear-end collision. Int J Legal Med. 2001;114:316-322.

45 Marshall PD, O’Connor M, Hodgkinson JP. The perceived relationship between neck symptoms and precedent injury. Injury. 1995;26:17-19.

46 Kasch H, Stengaard-Pedersen K, Arendt-Nielsen L, et al. Headache, neck pain, and neck mobility after acute whiplash injury: a prospective study. Spine. 2001;26:1246-1251.

47 Carroll L, Mercado AC, Cassidy JD, et al. A population-based study of factors associated with combinations of active and passive coping with neck and low back pain. J Rehabil Med. 2002;34:67-72.

48 Buitenhuis J, Spanjer J, Fidler V. Recovery from acute whiplash: the role of coping styles. Spine. 2003;28:896-901.