Snake and Other Reptile Bites

Definitions and Characteristics

Two main families of venomous snakes indigenous to the United States are Crotalidae (pit vipers) and Elapidae (coral snakes). Most snakebites are caused by the pit vipers, so called because of a depression, or pit, in the maxillary bone. Rattlesnakes (see Plate 7), the cottonmouth (water moccasin) snake (see Plate 8), and the copperhead snake (see Plate 9) are members of the pit viper family. The major snakes of medical importance outside of North America are the cobras, mambas, kraits, coral snakes, Australian elapids, sea snakes, vipers, rattlesnakes, asps, and colubrids (rear-fanged snakes). The fastest pit viper can crawl at a maximum speed of approximately 4.8 km/hr (3 mph). The speed of a pit viper’s strike has been clocked at 2.4 m/sec (8 ft/sec); the snake can reach distances of approximately one-half its body length.

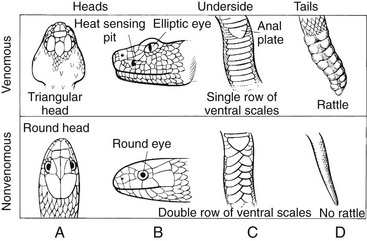

Identifying characteristics of pit vipers include the following (Fig. 37-1):

1. Depression, or pit, in the maxillary bone, located midway between and below the level of the eye and the nostril on each side of the head

2. Vertical elliptic pupils (“cat’s eye”)

3. Triangular head that is distinct from the remainder of the body

4. Single row of subcaudal scutes, or scales

Two members of the coral snake family, Elapidae, are found in the United States: the western coral snake (Micruroides euryxanthus) (see Plate 10), found in Arizona and New Mexico, and the eastern coral snake (Micrurus fulvius) (see Plate 11), distributed from coastal North Carolina through the Gulf states to western Texas. The elapids differ from pit vipers in having very short fangs, round pupils, and subcaudal scales in a double row. Because many nonpoisonous mimics occur in coral snake territory, the rule of thumb for identifying a venomous species is that red bands bordered by yellow or white indicate a venomous reptile, whereas red bands bordered by black indicate a nonvenomous reptile. This rule applies to all coral snakes native to the United States but does not apply to species found south of Mexico City and in other non-U.S. countries. A few essentially harmless, rear-fanged colubrid snakes in the United States, such as the night snake and lyre snake, possess elliptic pupils but lack facial pits.

Pit Viper Envenomation

Signs and Symptoms

1. Common: local burning pain immediately after the bite, weakness, nausea and vomiting, paresthesias, pain, fang marks, swelling and edema (usually within 5 minutes), faintness, dizziness

2. Less common: ecchymosis, fasciculations, hypotension, bullae, necrosis, thirst, increased salivation, unconsciousness, blurred vision, increased respiratory rate

a. May have rapidly progressing edema that can involve an entire extremity within 1 hour if envenomation is severe (Table 37-1)

Table 37-1

| ENVENOMATION | CHARACTERISTICS |

| None | Fang marks, but no local or systemic reactions |

| Minimal | Fang marks, local swelling and pain, but no systemic reactions |

| Moderate | Fang marks and swelling progressing beyond the site of the bite; systemic signs and symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, paresthesias, or hypotension |

| Severe | Fang marks present with marked swelling of the extremity, subcutaneous ecchymosis, severe symptoms including manifestations of coagulopathy |

b. Usually spreads more slowly, over 6 to 12 hours

c. Edema that is soft, pitting, and limited to subcutaneous tissues

4. Hemorrhagic blebs and bullae developing at the site of the bite within hours to days.

5. Paresthesias of the scalp, face, and lips, along with periorbital muscle fasciculations, indicating that a significant envenomation has occurred

6. Hemorrhage manifested as skin petechiae, epistaxis, hematemesis, melena, hemoptysis, and blindness; pulmonary edema possible

7. With some Mohave Desert rattlesnakes, bites produce neuromuscular blockade, leading to respiratory paralysis, in the absence of a significant local tissue reaction. Paralysis initially appears as cranial nerve deficits (hoarseness, difficulty swallowing, ptosis) and progresses to involve the diaphragm.

Treatment

1. Direct treatment at reducing venom effects, minimizing tissue damage, and preventing complicated sequelae.

2. Provide out-of-hospital management.

a. Avoid panic. Instruct the patient to back out of the snake’s striking range, which is approximately the length of the snake.

b. Attempts to secure or kill the snake are not recommended because of the risk for additional bites to the patient or rescuer and because precious time can be lost. Absolute identification of the snake is not necessary for treatment. However, if the snake has been killed and plans are made to transport it, do not handle it directly; arrange to transport it in a closed container. Handle the snake using a stick that is longer than the snake. A severed snake head may envenom for 20 to 60 minutes after decapitation. If a photograph of a snake can be taken from a safe distance, this can be used for identification.

c. Immobilize the bitten extremity by splinting as if for a fracture. Keep the limb well padded at heart level (neither elevated nor lowered) in a position of function. Measure the bitten limb’s circumference at two or more sites every 15 minutes, and mark areas of redness and swelling with a pen.

d. Obtain medical assistance. Arrange for the patient to be transported to the nearest medical facility, with minimal exertion.

e. Encourage the patient to drink liquids to maintain adequate hydration.

f. Treat pain (IV, IM, or SC opioids preferred if available)

g. Remove any tight clothing or jewelry from involved extremities, and anticipate swelling.

3. The pressure immobilization technique (see later for coral snakebite treatment) is not routinely recommended. If it is employed, the bandage should not be removed until antivenom is ready to infuse (if asymptomatic) or is infusing (if symptomatic) because of a potential bolus venom release after its removal. This technique may be considered in high-risk cases. High risk for potentially severe envenomation may include cases that involve large snakes, particularly venomous snakes, or when there is a history of prolonged fang contact. Risks for poor outcome may be higher in patients with previous venomous snakebites (treated or not) and in those who experience delays to medical care and antivenom administration.

4. Several old and scientifically unproven remedies are no longer recommended for snakebite (Box 37-1).

a. Application of a tourniquet is no longer advised. An arterial-occlusive tourniquet represents a decision to sacrifice a limb to minimize systemic symptoms and save a life but has not been proven effective and may be harmful. A lympho-occlusive (a pressure of ≈20 mm Hg) constriction band applied proximal to the bite has been suggested but never proven to be helpful. If this method is chosen, take care to allow arterial inflow to the affected limb.

b. Incision and suction of the bite wound by mouth is not recommended.

c. Incision of the bite site across fang marks is not recommended.

d. Use of a negative-pressure device in an attempt to extract venom is not recommended. The Extractor was claimed to remove a clinically significant amount of venom if applied over the bite site within 3 minutes of the bite and left in place for 30 to 60 minutes. However, it may also promote local necrosis in the pattern of the applied suction, and studies discourage its use.

e. Electric shock therapy can be dangerous to patients and has no proven value in managing bites by venomous snakes.

f. Immersion cryotherapy is not recommended because freezing or vasoconstricting already compromised tissues may contribute to necrosis. Local application of ice to the bite wound as a first-aid measure is not recommended.

5. Antivenom use in the field can be recommended only when a qualified physician is on the scene and when all equipment (including definitive airway management equipment) and drugs are available to manage a potential anaphylactic/anaphylactoid reaction to the serum. Backpacking the extensive equipment and drugs necessary to administer intravenous antivenom is cumbersome, and severe anaphylaxis must be anticipated. The currently recommended antivenom product for pit viper envenomations in North America, CroFab, poses a lesser risk for severe allergic reaction and may prove to be safe enough for field use, but it is not yet recommended for out-of-hospital use.

6. Prophylactic antibiotics are unnecessary in most cases. However, if the delay to definitive care will exceed 5 hours, administer a broad-spectrum antibiotic, such as dicloxacillin or cephalexin 250 to 500 mg PO q6h, for 7 to 10 days.

7. Caregivers should ensure that the patient is adequately immunized against tetanus upon arrival at a medical facility.

Coral Snake Envenomation

Signs and Symptoms

1. Little or no pain and no local edema or necrosis; fang marks may be difficult to see; venom primarily neurotoxic

2. Within 90 minutes of envenomation, weak or numb feeling in bitten extremity

3. Several hours later, systemic symptoms appear, including tremors, drowsiness or euphoria, and marked salivation; systemic signs and symptoms may be delayed as long as 13 hours after significant bites and can then progress rapidly.

4. After 5 to 10 hours, slurred speech and diplopia develop as cranial nerve palsies evolve.

5. Paresthesias and muscle fasciculations common at the site of the bite

6. Flaccid paralysis, respiratory failure

7. Nausea and vomiting, weakness, dizziness, difficulty breathing

8. Less common: local edema, diplopia, dyspnea, diaphoresis, myalgia, confusion

Treatment

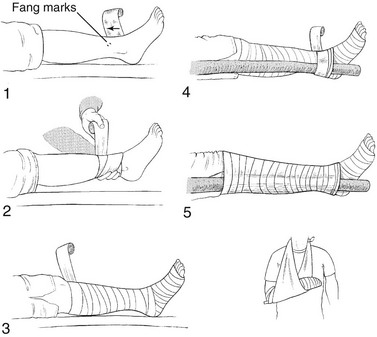

1. Apply the pressure immobilization technique. This technique (Fig. 37-2) has been used successfully to manage certain elapid snakebites and funnel-web spider bites in Australia and marine envenomations. The efficacy of the technique depends on collapsing small, superficial lymphatic and venous vessels to retard venom uptake and distribution. Possible disadvantages include increased local tissue damage in crotalid bites because of the necrotizing effect of the venom if it remains localized to certain sites over time. Therefore it is not recommended for use but might on rare occasion be considered when the deleterious local effects must be balanced against a life-threatening situation that follows the systemic distribution of venom. This technique may be considered in high-risk cases. High risk for potentially severe envenomation may include cases that involve large snakes, particularly venomous snakes, or when there is a history of prolonged fang contact. Risks for poor outcome may be higher in patients with previous venomous snakebites (treated or not) and in patients who experience delays to medical care and antivenom administration.

a. To apply the pressure immobilization technique for venom sequestration, if the bite location permits, place a cloth or gauze pad (6 to 8 cm [2.4 to 3.1 inches] by 6 to 8 cm by 2 cm [0.8 inch] thick) directly over the area and hold it firmly in place with a circumferential bandage 15 to 18 cm (5.9 to 7 inches) wide applied at lymphatic-venous occlusive pressure. If the cloth or gauze pad is not available, the circumferential bandage may be used alone. Take care not to occlude the arterial circulation, as determined by the detection of arterial pulsations and proper capillary refill.

b. Splint the limb, and do not release the bandage until after the patient has been transported to definitive medical care, or after 24 hours. Take care to check frequently that swelling beneath the bandage has not compromised the arterial circulation.

2. Note that because it is difficult to ascertain early whether envenomation by a coral snake has occurred, treatment and observation are mandatory. Early treatment with antivenom is advised in any suspected bite with envenomation because signs and symptoms can be delayed in onset. Therefore, transport the bitten patient to a medical facility where antivenom therapy can be administered.

3. North American Coral Snake Antivenom is effective against eastern coral snake (M. fulvius) and Texas coral snake (M. fulvius tenere) envenomations. The single existing lot (4030026) has an extended expiration date of October 2013 and will be continually reevaluated by the Food and Drug Administration for stability until a new lot is manufactured. For assistance with suspected envenomation or current information about antivenom availability, contact a local snakebite specialist or the poison control center at 1-800-222-1222 or online at http://www.poisoncentertampa.org/antivenin/coral-snake-antivenin.aspx.

4. Monitor airway for swelling and difficulty breathing and swallowing.

5. Control pain with judicious titration of opiates (if available).

6. Avoid ineffective treatments that may cause the patient harm and delay transportation to definitive care (see Box 37-1).

Envenomation by Non–North American Snakes

Signs and Symptoms

1. For elapids (cobras, mambas, kraits, Australian venomous snakes, coral snakes):

a. Local: findings absent or minimal; significant pain with some species, regional lymphadenopathy and necrosis with some species, edema with some species

b. Systemic: neurotoxicity (cranial nerve dysfunction, ptosis, dysphonia, blurred vision, altered mental status, peripheral weakness and paralysis, respiratory failure) with delayed (up to 10 hours) onset possible, hypersalivation, diaphoresis, cardiovascular failure, coagulopathy, myonecrosis, renal failure

c. Eye exposure to venom from any of the spitting cobras or ringhals: immediate burning pain and tearing, which may lead to corneal ulceration, uveitis, and permanent blindness

a. Local: trivial tissue damage, fang marks difficult to identify, fangs or teeth may be left in wound

b. Systemic: neurotoxicity (cranial nerve dysfunction, peripheral weakness and paralysis, respiratory failure); hypersalivation; dysphagia; dysarthria; trismus; muscle spasm; myotoxicity with resulting muscle pain and tenderness; rhabdomyolysis; myoglobinemia; myoglobinuria; hyperkalemia

a. Local: pain, soft tissue swelling, regional lymphadenopathy, ecchymosis, bloody exudate from fang marks, hemorrhagic bullae; early absence of findings does not rule out significant envenomation; local necrosis possibly significant

b. Systemic: any organ system can potentially be involved; cardiovascular toxicity (hypotension, pulmonary edema); neurotoxicity (cranial nerve dysfunction, peripheral weakness) with some species; hemorrhagic diathesis; renal failure; altered taste sensation; headache; diarrhea; vomiting; fever; abdominal pain; hypotension

Treatment

1. Initiate same field treatment as for North American pit viper envenomation. Use the pressure immobilization technique for bites of elapids, sea snakes, burrowing asps, colubrids, and any unknown snake when the bite does not produce significant local pain.

2. Avoid wasting time on potentially dangerous therapies with no proven benefit (see Box 37-1).

3. Treat pain (acetaminophen or opiates preferred, avoid nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) because of increased risk for bleeding).

4. Treat nausea with ondansetron 4 to 8 mg PO or IV, or promethazine 12.5 to 25 mg IM.

5. Anaphylaxis should be treated with aqueous epinephrine 0.1% (1 : 1000) (0.3 to 0.5 mL in adults, 0.01 mL/kg in children) by intramuscular injection, followed by a histamine-1-blocker such as chlorpheniramine maleate (10 mg in adults, 0.2 mg/kg in children).

6. Treat respiratory distress by placing patient in the recovery position and providing supplemental oxygen if available. Patients with severe respiratory distress may require endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation.

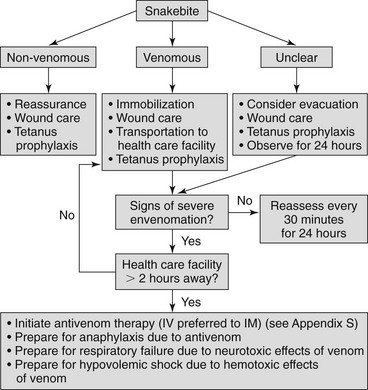

7. If in remote or wilderness setting, follow the algorithm in Figure 37-3 and arrange to transport the patient as quickly as possible to the nearest appropriate medical facility where antivenom therapy can be initiated (see Appendix S).

Venomous Lizard Bites

The Gila monster (see Plate 12) and Mexican beaded lizard (see Plate 13) are found in North America. Both possess venom glands and grooved teeth. Human envenomation most often occurs when the lizard retains its grasp and chews on the patient.

Signs and Symptoms

1. Usually simple puncture wounds, although teeth may break off or be shed during the bite and remain in the wound

2. Pain, often severe and burning, at the wound site within 5 minutes

a. Pain radiating up the extremity

b. Intense pain lasting 3 to 5 hours and then subsiding after 8 hours

3. Edema at the wound site, usually within 15 minutes, that progresses slowly in variable degrees up the extremity

4. Cyanosis or blue discoloration around the wound

5. Weakness, fainting, diaphoresis, nausea, vomiting, difficulty breathing, paresthesias

6. Tenderness at the wound site for 3 to 4 weeks after the bite, but usually little tissue necrosis

Treatment

1. Cleanse the wound thoroughly with a soap and water scrub or with a dilution of povidone-iodine.

2. Infiltrate the puncture wounds with 1% lidocaine using a 25-gauge needle, and then probe the wounds to detect the presence of shed or broken teeth, helping to prevent future infection from a foreign body.

3. Administer an analgesic appropriate for the degree of pain.

4. A bandage to stop bleeding and provide immobilization may be beneficial.

5. As with snakebites, avoid use of suction devices, ligatures, pressure immobilization, incisions, electrotherapy, and ice compression (see Box 37-1).