Chapter 43

Smoking Cessation

A Priority for the Cardiac Patient

1. Why is smoking cessation of fundamental importance in the management of the cardiac patient?

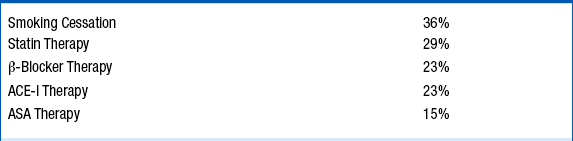

Smoking cessation is the most important of the modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The products of tobacco smoke contribute directly, and distinctly, to the development of atherosclerosis and the adverse consequences that follow (Box 43-1). The benefits of smoking cessation cannot be exaggerated. A rapid and sustained reduction in the likelihood of cardiac disease or a cardiac event occurs in those who successfully stop smoking; those with established cardiac disease experience a dramatic reduction in the likelihood of recurrence, complication, or death following cessation. In both instances, the benefits of smoking cessation accrue rapidly and reflect the elimination, rather than the ongoing management, of a major risk factor (Table 43-1). Smoking cessation should be accorded a priority in those with cardiac disease—in every professional setting—to do otherwise should be seen as reflective of substandard care.

TABLE 43-1

MORTALITY RISK REDUCTION IN THOSE WITH CORONARY HEART DISEASE

ACE, Angiotensin-converting enzyme; ASA, aspirin.

See: Critchley JA, Capewell S: Mortality risk reduction associated with smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease. A systematic review. JAMA 290:86-97, 2003.

2. Why have cardiologists neglected the treatment of tobacco addiction in the past?

3. What should every health care professional know about smoking?

Nicotine is the most addictive substance encountered in ones community. It takes only a few days to establish nicotine addiction once inhalation has been “mastered.” Thereafter, brain function, structure, and neurochemistry become transformed. Smokers smoke to ensure constant levels of nicotine—and the elevated levels of dopamine, and other neurotransmitters, whose release follows the stimulation of nicotine receptors. The cigarette is a perversely engineered drug-delivery device constructed to deliver a precise aliquot of nicotine as rapidly as possible. Following the inhalation of tobacco smoke, nicotine is delivered very rapidly via the arterial system to the brainstem where it initiates a cascade of neurotransmitter activity and dopamine release. Most smokers know why they shouldn’t smoke; most smokers do not want to be smokers; and many smokers will make one or two unassisted quit attempts each year—most of which will fail. Smokers generally do not need more education or lectures. They want help. Optimal cessation strategies involve the following:

Provision of pharmacotherapy to eliminate or curb the symptoms of withdrawal and craving that lead to the use of a cigarette

Provision of pharmacotherapy to eliminate or curb the symptoms of withdrawal and craving that lead to the use of a cigarette

Communication of strategic, tactical advice regarding the management of those circumstances, settings, and situations that typically accompany and stimulate smoking

Communication of strategic, tactical advice regarding the management of those circumstances, settings, and situations that typically accompany and stimulate smoking

4. How might smokers with cardiac disease be better assisted with cessation?

In hospitals and other settings, clinical protocols, care maps, and other systematized approaches to the identification and treatment of smokers are becoming the norm and greatly facilitate and enhance the care of patients addicted to tobacco (Box 43-2).

5. What is a good starting point for smoking cessation?

In the past, approaches to smoking cessation have placed an emphasis on patient preparation and planning prior to reaching a “quit date.” There is increasing evidence that asking about willingness to embark on a quit attempt at the time of a patient encounter can be very helpful, capitalizing on any recent clinical event and a patient’s interest in cessation. Even among those disinclined to make a quit attempt, the provision of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy, which will induce a decline in cigarette consumption, has been demonstrated to be effective in stimulating a quit attempt and cessation. This approach mirrors our initial prescription of lipid-lowering or antihypertensive medications: their effectiveness is evaluated in the weeks that follow, when retitration of therapy may be necessary. This reduce-to-quit (RTQ) paradigm may be particularly appropriate in the cardiac setting, where further follow-up is likely to occur. Both the patient and clinician will be pleasantly surprised to note that cigarette consumption has fallen appreciably, serving as an appropriate entree to a more carefully planned cessation attempt with specific focus on titration of pharmacotherapy and ongoing follow-up (perhaps in association with the family physician).

6. How can one best use pharmacotherapy to optimize the likelihood of cessation?

7. Can NRT be initiated in the in-patient setting in patients with cardiac disease?

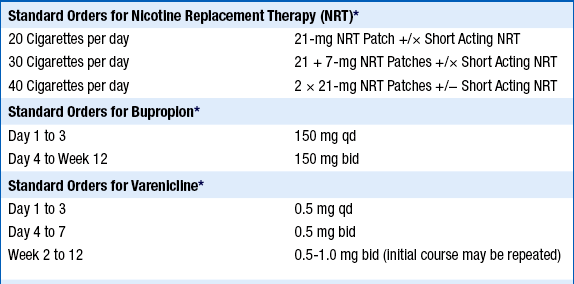

Yes. NRT may be offered to smokers within hours of patient admission—nicotine withdrawal will occur rapidly in many smokers, producing discomfort, a variety of behavioral challenges for clinical staff, and complicating compliance with treatment of their cardiac condition. Evidence has been accumulating for years attesting to the safety of NRT in cardiac patients. Nicotine in this setting is delivered slowly via the venous system (not the arterial system, as is the case with smoking); achieves steady state levels that will always be far less than those to which a smoker has been accustomed; is not accompanied by carbon monoxide and countless other toxins; and, is being provided to patients who have developed marked tolerance to the cardiovascular effects of nicotine. A standardized order template may be useful (Table 43-2).

TABLE 43-2

UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA HEART INSTITUTE STANDARD ORDERS FOR NICOTINE REPLACEMENT THERAPY, BUPROPION, AND VARENICLINE

Short Acting NRT, is an NRT inhaler, NRT lozenge, NRT spray, or NRT gum.

∗In each case, be prepared to titrate therapy to ensure control of withdrawal and craving or to address dose-related side effects. Therapy may be prolonged as is necessary in order to prevent relapse to smoking. Consideration may be given to combining therapies in those in whom single-agent treatment is insufficient to address symptoms of withdrawal and craving and/or in whom total cessation has not been achieved.

8. What if a smoker reports that NRT has not decreased their desire to smoke?

Many smokers will report that the use of NRT is not associated with any decrease in the desire to smoke—a classic indication of underdosing. It has been calculated that the standard doses of NRT, for example, will not meet the nicotine “needs” of a majority of current smokers. Smokers are able to titrate nicotine intake with considerable precision; thus, the use of a nicotine inhaler in association with a nicotine patch will allow the emerging nonsmoker to titrate nicotine to meet particular needs—usually at times of more intense cravings or withdrawal. Use of NRT, as with every cessation pharmacotherapy can be continued until its discontinuation is not accompanied by an urge to smoke or a lapse to smoking in response to certain stimuli or surroundings. It is exceptionally rare for patients to become NRT dependent.

9. Can bupropion be useful for smoking cessation?

10. Can varenicline be useful for smoking cessation?

Varenicline acts as an α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist and partial antagonist. As such, it stimulates this receptor, triggering a degree of dopamine release in the forebrain while occupying, and blocking, the receptor site, preventing nicotine from exerting any effect if smoking occurs. Most patients receiving varenicline experience little or no craving for nicotine and, if a cigarette is smoked, derive no sensation or “benefit” typically associated with smoking. It has been shown to be the most effective single agent in inducing cessation and has demonstrated effectiveness in those with stable cardiovascular disease. Concerns have been raised about an increase in cardiovascular events among those using this medication. However, no clear evidence of a causal relationship has been identified, nor has a biologically plausible reason for any such effects been identified, and the publication of a recent meta-analysis has dispelled those concerns. The risks of any smoking cessation pharmacotherapy must always be considered against the risks of continued smoking. The principal side effect of varenicline is nausea, which can typically be managed by taking the medication with meals and a full glass of water, or by reducing the dose.

Bibliography, Suggested Readings, and Websites

1. Aboyans, V., Thomas, D., Lacroix, P. The cardiologist and smoking cessation. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2010;25:469–477.

2. Ambrose, J., Barua, R. The pathophysiology of cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: an update. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1731–1737.

3. Benowitz, N., Gourlay, S. Cardiovascular toxicity of nicotine: implications for nicotine replacement therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1422–1431.

4. Benowitz, N.L. Cigarette smoking and cardiovascular disease: pathophysiology and implications for treatment. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;46:91–111.

5. Benowitz, N.L. Neurobiology of Nicotine Addiction: Implications for Smoking Cessation Treatment. Am J Med. 2008;121(4A):S3–S10.

6. Critchley, J.A., Capewell, S. Mortality risk reduction associated with smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;290:86–97.

7. Ebbert, J.O., Burke, M.V., Hays, J.T., et al. Combination treatment with varenicline and nicotine replacement therapy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:572–576.

8. Erhardt, L. Cigarette smoking: an undertreated risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2009;205:23–32.

9. Fiore, M.C., Jaen, C.R., Baker, T.B., et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update clinical practice guideline. Rockville, Md: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008.

10. Hubbard, R., Lewis, S., Smith, C., et al. Use of nicotine replacement therapy and the risk of acute myocardial infarction, stroke, and death. Tob Control. 2005;14:416–421.

11. Hurt, R.D., Dale, L.C., Offord, K.P., et al. Serum nicotine and cotinine levels during nicotine-patch therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1993;54:98–106.

12. Hurt, R.D., Sachs, D.P., Glover, E.D., et al. A comparison of sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1195–1202.

13. Jorenby, D.E., Hays, J.T., Rigotti, N.A., et al. Efficacy of varenicline, and α4 β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:56–63.

14. Pipe, A. Tobacco and cardiovascular disease: achieving smoking cessation in cardiac patients. In Yusuf S., ed.: Evidence based cardiology, ed 3, Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishing, 2010.

15. Prochaska, J.J., Hilton, J.F. Risk of cardiovascular serious adverse events associated with varenicline use for tobacco cessation: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e2856.

16. Rigotti, N.A., Pipe, A.L., Benowitz, N.L., et al. Efficacy and safety of varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with cardiovascular disease: a randomized trial. Circulation. 2010;121:221–229.