CHAPTER 20 Small to Medium Rotator Cuff Tears

Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (ARCR) has become the gold standard for treatment of the vast majority of rotator cuff lesions.1–16 Early concerns about repair integrity and durability have led to the anticipated evolution in anchors, suture material and, most importantly, surgical technique. We now have at our disposal an armamentarium of anchors made not only of metal, but poly-L-lactic acid, self-reinforced poly-DL-lactic acid, and polyetheretherketone (PEEK). Suture material has been vastly improved as a result of the introduction of Fiberwire and the many comparable enhanced strength suture materials.

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS

With this infomation, the patient is appropriately counseled on the advisability of surgery, including its associated risks and potential outcomes. There has been ongoing debate regarding the need for surgical intervention in these smaller tears; however, most surgeons recognize the potential for enlargement of any tear over time, especially those with a traumatic cause. Currently, for any patient with a well-defined traumatic event, and otherwise normal shoulder function prior to that event, the recommendation is for immediate repair. Those individuals with no history of substantial trauma, yet ongoing symptoms and MRI confirmation of a tear, conservative nonsurgical care is offered, with the recommendation for follow-up and possible repeat MRI at 4 to 6 months. If symptoms are persistent, or are unrelieved with conservative measures, surgery and repair are recommended. Also, those patients with significant comorbidities that could strongly affect healing and/or rehabilitation, and those with compliance issues, are treated with conservative modalities, and surgery is reserved for those with increasing symptoms.

ARTHROSCOPIC ROTATOR CUFF REPAIR

Setup

All cases are performed with the patient in the lateral decubitus position, allowing ready access to the posterior, anterior, and superior aspects of the shoulder while holding the arm in a position of slight abduction, thereby facilitating approximation of the free tendon edge to the region of the greater tuberosity (Fig. 20-1). The arm is rotated as needed to optimize anchor placement and reduce tension during suture tying. In most patients, 10 pounds of traction at approximately 30 to 40 degrees of abduction is more than adequate to provide the proper shoulder position. Anesthesia is moved out of the immediate operative field to allow unimpeded access to the entire shoulder region.

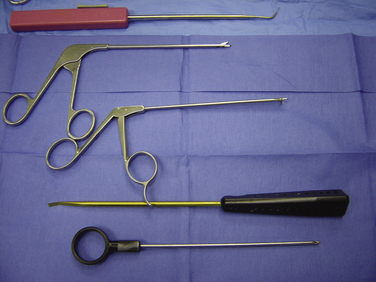

Every procedure begins with a basic set of instruments, including a simple knot pusher, ring grabber or crab claw device for retrieving individual sutures, set of cannulated suture passers, cannula for fluid management, and various suture retrievers (Fig. 20-2). Additional instruments can be added as neededs.

Portals

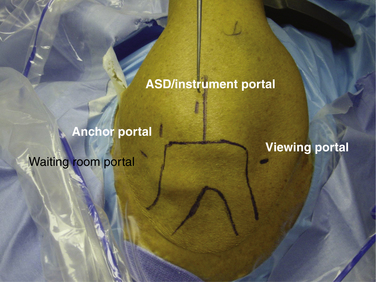

All arthroscopic repairs require three principal portals and an additional ancillary anterior portal. The viewing portal is located 1 cm medial and 2 cm inferior to the posterolateral corner of the acromion (Fig. 20-3). The arthroscopic subacromial decompression (ASD) instrument portal is located immediately anterior to the finish line, a line drawn perpendicular to the lateral margin of the acromion, beginning at the posterior extent of the acromioclavicular joint and 2 to 3cm lateral to the lateral margin of the acromion. The anchor portal location is determined during subacromial viewing using the needle localization technique; it is typically at the anterolateral corner of the acromion. An additional fourth portal may be made anterior to the acromion, called the waiting room portal. I use this for large tears in which three or more anchors and six or more sutures are involved. This portal allows me to dock sutures that are not being worked with anteriorly to free up the viewing area while posterior sutures are tied. This aids greatly in suture management.

Once the need for a repair has been determined, all portals are secured with cannula. The size of the cannula is dependent on the anticipated use of that portal. For example, the posterior portal is often used also for instrument access with the Spectrum (Conmed Linvatec, Largo, Fla) cannulated suture passer. This device requires at least an 8-mm opening and thus an 8-mm cannula. The anchor portal, however, is used almost exclusively for anchor insertion and knot tying, so a smaller 5-mm cannula is adequate. The lateral, or instrument portal, is sized according the instrument to be used for that repair. In most cases, and with most instruments, a 6- to 7-mm cannula is acceptable. Use of a cannula greatly diminishes fluid extravasation into the soft tissue, minimizes overall fluid requirements, and enhances visualization by maintaining hydrostatic pressure in the subacromial space. Cannulas also allow the surgeon to move the scope freely from portal to portal to improve visualization and prevent soft tissue from being entangled with sutures during passage and tying.

Acromioplasty

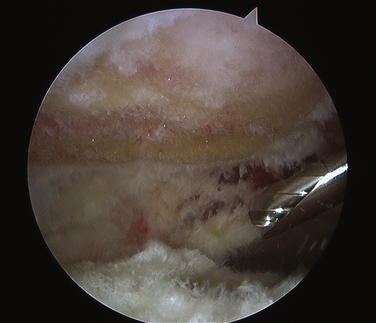

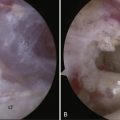

Although there has been debate regarding the need and efficacy of ASD in ARCR,17–19 an acromioplasty allows for enhanced visualization during the repair and increased room for instrumentation, and lessens the likelihood of later impingement of the repaired cuff. The ASD should require no more than 10 to 15 minutes to complete. To that end, in all chronic and many acute full thickness rotator cuff tears, I routinely perform a concomitant ASD. Viewing from the posterior portal, a bursectomy is performed to visualize the inferior surface of the acromion. If a large rotator cuff tear has been identified, the bursectomy is carried around the anterior, lateral, and posterior gutters to improve visualization and facilitate instrumentation of the subscapularis and/or infraspinatus tendons. When the bursectomy is complete, a radiofrequency (RF) device removes all residual soft tissue from the under surface of the acromion and releases the coracoacromial (CA) ligament from its attachment on the anteroinferior aspect of the acromion (Fig. 20-4). This is only a CA ligament release, not a resection. The burr is introduced from the lateral portal and the decompression begun at the anterolateral corner, working both medial and posterior (Fig. 20-5). An adequate decompression is achieved when the acromioplasty is tapered and terminates at or about the finish line (the line drawn at the time of initial portal placement; see earlier). Finally, the decompression is completed by moving the arthroscope to the lateral portal, bringing the burr in from the posterior portal and finished with a cutting block technique.

Mobilization and Tear Pattern Recognition

Many chronic, long-standing rotator cuff tears present with retracted margins, are adherent to the surrounding soft tissue, and require some sort of mobilization to facilitate a tension-free repair. There are four basic types of releases used in ARCRs—subacromial, paralabral capsulotomies, and anterior and posterior interval releases. The subacromial release is performed with traction sutures applied to the tendon edge while using a shaver or small periosteal elevator to tease the adherent tendon from the undersurface of the acromion. Paralabral capsulotomies are used in cases of significant medial retraction and/or thickened scarred capsule and are best performed at the time of glenohumeral inspection using a basket or RF device through an anterior portal to release the capsule selectively, just outside the labral margin. Anterior and posterior interval releases are used when there has been an asymmetrical medialization retraction of the supraspinatus or infraspinatus, as seen in L-shaped and reverse L-shaped tears.20 However, these are seldom needed for smaller, less retracted tears.

Anchor Placement

Increasingly, the recommendation has been for the use of DR repairs. Proponents argue that there are enhanced initial stability and repair construct fixation, with the anticipation of a lower retear rate postoperatively.21–28 If the tear is smaller and mobile, readily approximated to the tuberosity, a single-row (SR) repair can be used. In such cases, anchor placement will be at or just medial to the lateral margin of the greater tuberosity (Fig. 20-6). In larger tears, when a DR repair is desired, medial anchors are placed 5 mm lateral to the articular margin and lateral anchors at the greater tuberosity or just lateral to it (Fig. 20-7). After each anchor is placed, traction is applied to the sutures to verify anchor stability.

Suture Passing

As arthroscopic rotator cuff repair has evolved, so have the different techniques for suture passing. Early methods required the surgeon to pass the preloaded anchor through the tendon, anchor and all. Alternatively, the surgeon could pass the sutures through the tendon first and then load them on to the anchor, insert the anchor, and tie the sutures. Newer techniques and passing devices allow for initial anchor placement followed by suture passing via a number of different methods, each of which requires a specific instrument and skill set for its completion.

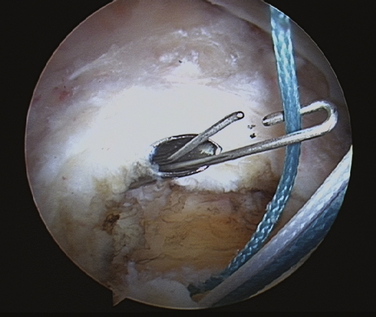

Antegrade Passers

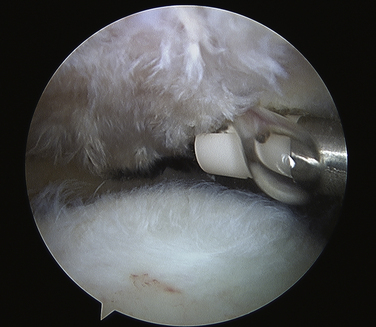

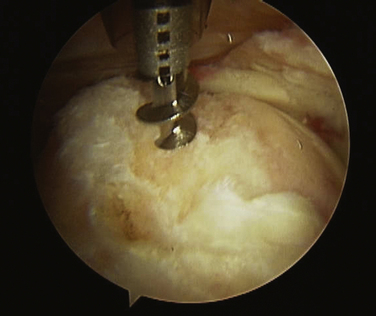

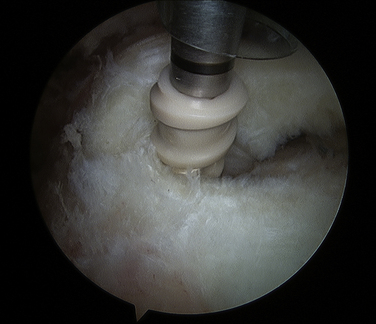

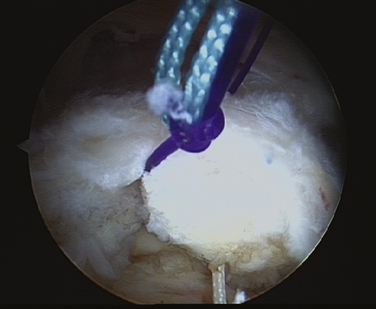

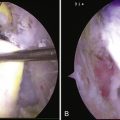

These devices have in common the ability to couple one limb of an anchor suture to its flexible needle, grasp the tendon edge, and drive the needle, with suture, through the tendon, where it is retrieved with a grasper. The advantages inherent in these instruments include the substantial depth of their bite from the tendon margin and reusability from case to case, with only needle replacement required. The technique begins with anchor placement, medially if a double row or laterally if a single row. While viewing from the posterior portal, individual sutures are retrieved from the anterior anchor portal and moved to the lateral portal, where they are loaded into the passer. The passer is introduced through the lateral portal into the subacromial space, the jaws are opened, and the passer is advanced medially to optimize tissue purchase (Fig. 20-8). Next, the jaws are closed and the needle, with suture attached, is driven from the articular to bursal surface of the tendon and retracted, leaving the suture loop on the bursal surface for retrieval (Fig. 20-9). If a DR repair is being performed, both limbs of each of the two anchor sutures are passed, creating a horizontal mattress stitch. The passed suture limbs are moved out of the immediate work area to the waiting room portal anteriorly and the process begins again with the next anchor.

Retrograde Snare Technique

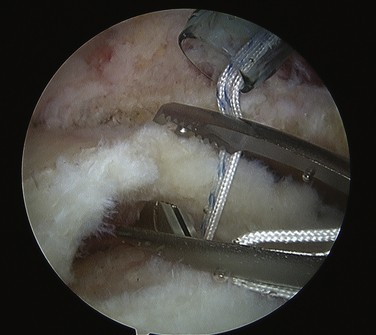

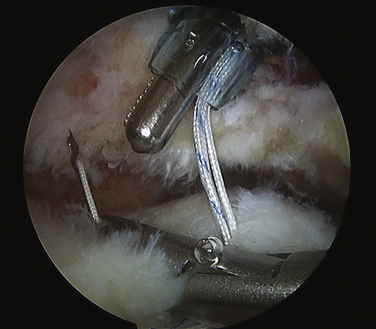

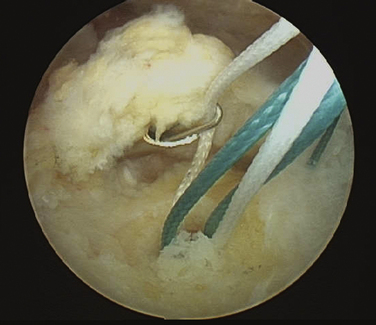

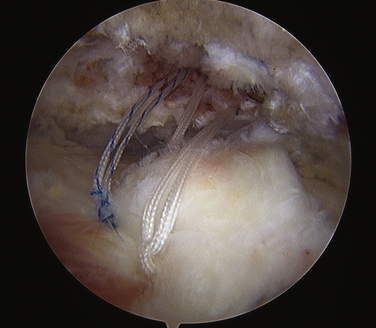

In this technique, viewing is done from the lateral portal. With anchors in place, the retrieval device is introduced from the posterior, waiting room, or anteromedial portal based on tear pattern. Most of these retrograde retrieval devices allow the surgeon to penetrate the tendon edge 1 to 2 cm medial to its lateral margin (Fig. 20-10). Once through the tendon, the snare is opened and an individual suture limb is grasped (Fig. 20-11). The snare is closed only enough to retain the suture but not so much as to impede its motion through the snare eyelet. The retriever is withdrawn, bringing the suture limb along and creating a simple suture pass through the tendon ready for tying. This process is repeated for all suture limbs of each double-loaded anchor.

Pulling Stitches or Suture Shuttles

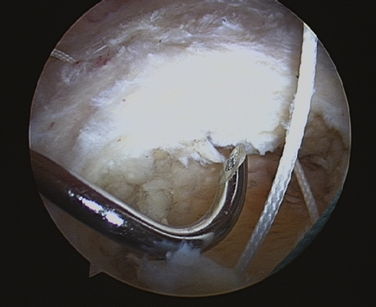

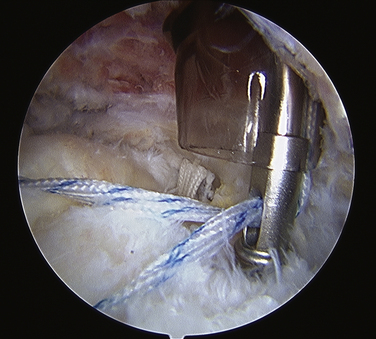

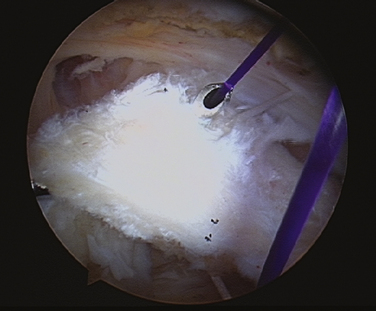

There are a number of commercially available devices that allow the passage of a monofilament suture or a shuttle device. In both scenarios, the instrument penetrates the tendon on the articular or bursal surface of the tendon (Fig. 20-12) and deploys the suture or retrieval loop once it is through the tendon, where it is grasped and brought out a separate portal (Fig. 20-13). One limb of the anchor suture is retrieved along with the monofilament shuttle suture, which is then tied around the anchor suture limb (Fig. 20-14). The other end of the monofilament suture is pulled, bringing the anchor suture back through the tendon edge in retrograde fashion and out the portal (Fig. 20-15). In similar fashion, a twisted loop of Nitinol can be used to capture the anchor suture. Both techniques are simple and effective and can be performed using a number of different devices. The disadvantage in both is the additional step necessary first to pass the suture or wire, couple it to the anchor suture, and finally pull the anchor suture retrograde through the tendon to create the simple stitch. However, in situations in which there is little room available for larger instruments, as is often the case with small tears, this technique works well.

FIGURE 20-13 After the passer penetrates the tendon, the monofilament suture is deployed into the subacromial space.

Knot Tying

A number of different arthroscopic knots have been described and each has its applicability and its proponents. The surgeon should become familiar and comfortable with one knot and proficient in its use. I use the SMC (Samsung Medical Center) knot, which has excellent sliding and locking characteristics, is a simple knot to tie and teach, and is very reproducible. The first step in knot tying is identification of the initial post, which should be the suture end that passes through the rotator cuff tendon. It is on this post that the sliding knot will be tied and introduced into the subacromial space. I shorten the first post and hold it in my left hand to accommodate for the length gained when the knot is pulled into the shoulder, and keep the two suture limbs even. The knot is made by bringing the long limb in the right hand around the index finger, under the left hand post limb, and back over both suture. This limb is then retrieved by reaching through the interval between the two sutures, brought back through them and, while pronating with the left hand, the right hand passes the nonpost limb through the D-shaped space created with the earlier maneuvers. The slack is taken out of the knot but is not tightened. The knot pusher is placed over the initial post, pushing the sliding knot down into the subacromial space to the tendon. Gentle traction is applied simultaneously on the initial left hand post while pushing the knot against the tendon, which will tighten the knot, and it is set and locked into place by pulling on the opposite right hand post. The final step consists of placing three half-hitches, reversing the throw and alternating the post each time. The knot pusher becomes a puller to deliver the half-hitches. The suture is then cut and its stability confirmed. This process is repeated for each subsequent suture.

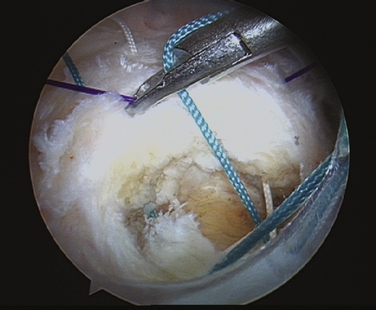

Knotless Devices

When any of these devices are used in a double-row construct, the medial anchors are placed first, their sutures passed, and the medial suture limbs coupled to a lateral anchor. The medial sutures can be tied (Fig. 20-16), creating the medial row of fixation, and then brought out to the lateral anchor for fixation and creation of the second row of the DR (Figs. 20-17 and 20-18). Alternatively, these medial anchors sutures can be directly coupled to the lateral anchor without being tied medially.

Procedural Steps

PEARLS& PITFALLS

PEARLS

1. Anderson K, Boothby M, Aschenbrener D, van Holsbeeck M Outcome and structural integrity after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using 2 rows of fixation: minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med, 34; 2006:1899-1905.

2. Bennett WF Arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears: a prospective cohort with 2- to 4-year follow-up. Arthroscopy, 19; 2003:380-390.

3. Burkhart SS, Barth JR, Richards DP, et al. Arthroscopic repair of massive rotator cuff tears with stage 3 and 4 fatty degeneration. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:347-354.

4. Burkhart SS, Danaceau SM, Pearce CEJr Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: Analysis of results by tear size and by repair technique-margin convergence versus direct tendon-to-bone repair. Arthroscopy, 17; 2001:905-912.

5. Burns JP, Snyder SJ. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in patients younger than fifty years of age. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:90-96.

6. Cole BJ, McCarty LP3rd, Kang RW, et al Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: prospective functional outcome and repair integrity at minimum 2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg, 16; 2007:579-585.

7. Fouse M, Nottage WM. All-arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2007;15:208-215.

8. Gartsman GM, Khan K, Hammerman SM. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:832-840.

9. Jones CK, Savoie FH3rd. Arthroscopic repair of large and massive rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:564-571.

10. Krishnan SG, Harkins DC, Schiffern SC, et al. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff in patients younger than 40 years. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:324-328.

11. Lafosse L, Brzoska R, Toussaint B, Gobezie R. The outcome and structural integrity of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair with use of the double-row suture anchor technique. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(suppl 2, pt 2):275-286.

12. Murray TFJr, Lajtai G, Mileski RM, Snyder SJ Arthroscopic repair of medium to large full-thickness rotator cuff tears: outcome at 2- to 6-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg, 11; 2002:19-24.

13. Ozbaydar MU, Bekmezci T, Tonbul M, Yurdo_lu C. The results of arthroscopic repair in partial rotator cuff tears. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2006;40:49-55.

14. Sugaya H, Maeda K, Matsuki K, Moriishi J. Repair integrity and functional outcome after arthroscopic double-row rotator cuff repair. A prospective outcome study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:953-960.

15. Wilson F, Hinov V, Adams G Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff: 2- to 14-year follow-up. Arthroscopy, 18; 2002:136-144.

16. Wolf EM, Pennington WT, Agrawal V Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: 4- to 10-year results. Arthroscopy, 20; 2004:5-12.

17. Gartsman GM, O’Connor DP Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair with and without arthroscopic subacromial decompression: a prospective, randomized study of one-year outcomes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg, 13; 2004:424-426.

18. Milano G, Grasso A, Salvatore M, et al Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair with and without subacromial decompression: a prospective randomized study. Arthroscopy, 23; 2007:81-88.

19. Nottage WM. Rotator cuff repair with or without acromioplasty. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(suppl 1):229-232.

20. Tauro JC. Arthroscopic “interval slide” in the repair of large rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:527-530.

21. Lo IK, Burkhart SS Double-row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: re-establishing the footprint of the rotator cuff. Arthroscopy, 19; 2003:1035-1042.

22. Mazzocca AD, Millett PJ, Guanche CA, et al. Arthroscopic single-row versus double-row suture anchor rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1861-1868.

23. Smith CD, Alexander S, Hill AM, et al. A biomechanical comparison of single and double-row fixation in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2425-2431.

24. Charousset C, Grimberg J, Duranthon LD, et al Can a double-row anchorage technique improve tendon healing in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair?: A prospective, nonrandomized, comparative study of double-row and single-row anchorage techniques with computed tomographic arthrography tendon healing assessment. Am J Sports Med, 35; 2007:1247-1253.

25. Franceschi F, Ruzzini L, Longo UG, et al Equivalent clinical results of arthroscopic single-row and double-row suture anchor repair for rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med, 35; 2007:1254-1260.

26. Lafosse L, Brozska R, Toussaint B, Gobezie R. The outcome and structural integrity of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair with use of the doble-row suture anchor technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1533-1541.

27. Yanke A, Provencher MT, Cole BJ. Arthroscopic double-row and “transosseous-equivalent” rotator cuff repair. Am J Orthop. 2007;36:294-297.

28. Grasso A, Milano G, Salvatore M, et al Single-row versus double-row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a prospective randomized clinical study. Arthroscopy, 25; 2009:4-12.