Chapter 10 Small-Caliber Endoscopy

![]() Video related to this chapter’s topics: Small-Caliber Endoscopy

Video related to this chapter’s topics: Small-Caliber Endoscopy

Introduction

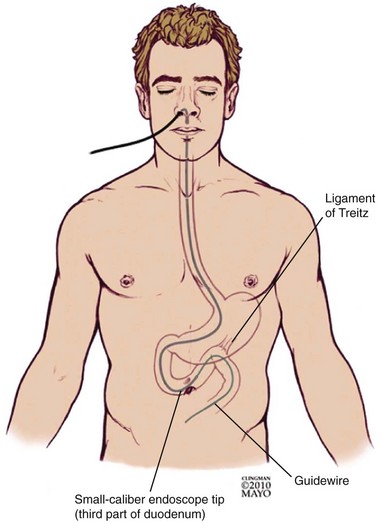

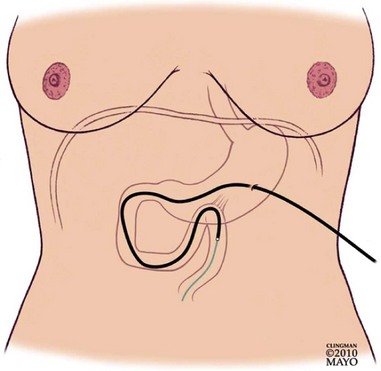

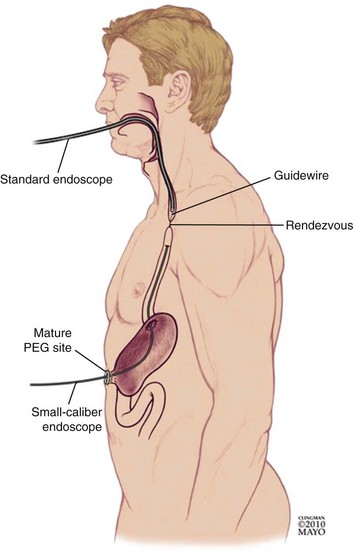

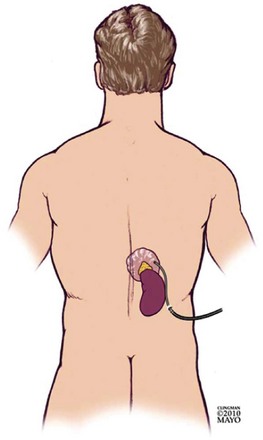

Small-caliber endoscopy has other practical uses. Patients who may be predictably intolerant of endoscopy with sedation, such as young patients, are potential candidates for this option. Small-caliber endoscopy offers a dramatically reduced procedure stress for patients who have fragile cardiopulmonary disease. The small-caliber endoscope provides an effective and well-tolerated option for the placement of transnasal feeding tubes and the placement of jejunal extensions via an existing percutaneous feeding gastroscopy site.1–3 Patients with high-grade esophageal strictures with existing percutaneous feeding gastrostomy may have primary or rendezvous attempts at dilation with placement of guidewires using a small-caliber endoscope via the gastrostomy site.4,5

Small-Caliber Endoscopy Insertion Techniques

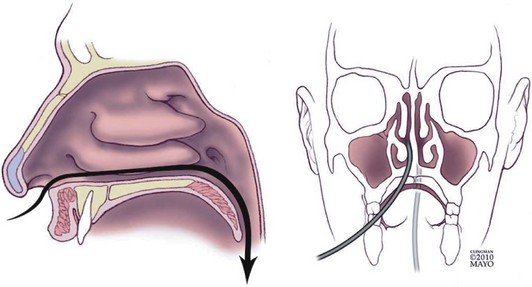

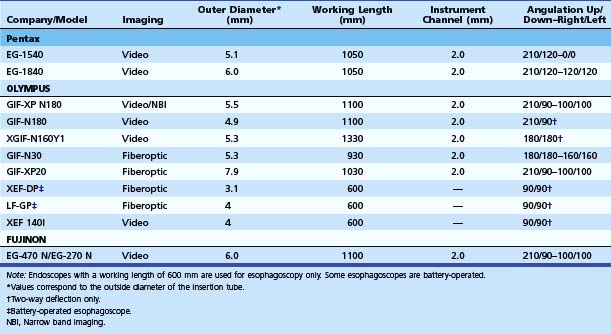

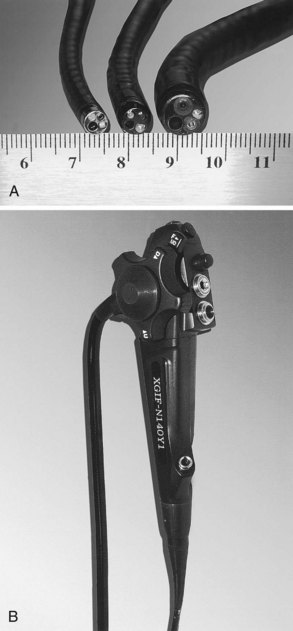

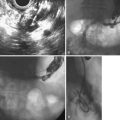

Small-caliber upper endoscopy can be performed either transnasally or perorally (Fig. 10.1). Transnasal endoscopy is feasible with endoscopes measuring 6 mm or less in outside diameter. Table 10.1 summarizes specifications of small-caliber endoscopes used in the reviewed studies and other endoscopes that are commercially available. Both videoesophagogastroduodenoscopes and esophagoscopes are currently available. Videoesophagogastroduodenoscopes have a working length of 1030 to 1330 mm, and esophagoscopes have a working length of only 600 mm. The outer diameter of videoesophagogastroduodenoscopes is between 5.1 mm and 6 mm. Esophagoscopes have an outside diameter between 3.1 mm and 4 mm. The relative outside diameters of small-caliber pediatric and conventional esophagogastroduodenoscopes are shown in Fig. 10.2A. Some esophagogastroduodenoscopes allow right and left and up and down angulation, whereas others provide only up and down angulation (Fig. 10.2B).

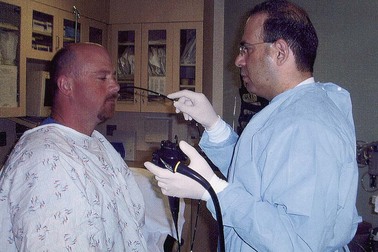

The procedure can be performed either in the standard left lateral decubitus position for conventional endoscopy or in the upright position (Fig. 10.3). Whether the upright position decreases the aspiration risk is unknown. The transnasal procedure should be performed with minimal air insufflation. The endoscope should be inserted slowly and gently, keeping the insertion tube of the endoscope straight such that it passes along the floor and septum of the nasal cavity and it does not migrate upward and laterally into turbinates interrupting passage, causing pain, and inducing bleeding. Slow progressive insertion with flexion of the endoscope tip over the base of the tongue is recommended for unsedated peroral examinations. Vigorous movements of the endoscope cause greater nasal discomfort with the transnasal route and more gagging with the peroral approach. During the procedure, conversing with the patient and pointing out findings on the video monitor reassure patients and may improve tolerability and reduce discomfort.

Unsedated Small-Caliber Upper Endoscopy

Technical Feasibility of Unsedated Small-Caliber Endoscopy

Feasibility of unsedated small-caliber endoscopy is mainly a subjective measure defined by the endoscopist. It can be affected by many factors, including the diameter of the small-caliber endoscope, endoscope maneuverability, image quality, patient tolerability, and the skills of the endoscopist. Feasibility of unsedated endoscopy is particularly linked to tolerance, which is discussed in the next section. In the crudest sense, technical feasibility represents the successful completion of the intended procedure by intubating the duodenum if an EGD is being performed or intubating the stomach if esophagoscopy is being done. Several investigators have reported the feasibility of transoral or transnasal unsedated EGD.6–18 Most of these studies have not been prospective randomized controlled trials. The patient populations have been either small in size or not representative of the general U.S. population. Studies addressing the feasibility of EGD that warrant attention are described next.

Wilkins and coworkers6 randomly assigned 72 patients to undergo either unsedated small-caliber EGD or sedated conventional EGD. Despite a highly selected and motivated U.S. Air Force community population, only 29 of the 33 patients (88%) had a complete unsedated small-caliber EGD. In another controlled study, Mulcahy and coworkers7 compared the feasibility of unsedated small-caliber EGD with unsedated conventional EGD in 322 patients. EGD was completed in 160 of the 163 patients (98%) undergoing unsedated EGD with a 6-mm gastroscope compared with 145 of the 159 patients (91%) undergoing unsedated EGD with a 9.8-mm gastroscope. These investigators subsequently reported 39 (8%) failures in a prospective study of 508 patients undergoing routine unsedated gastroscopy.8 Failure was associated with larger scope diameter (>9 mm), higher preprocedure anxiety, and younger age.

Ristikankare and colleagues9 randomly assigned 180 patients undergoing EGD to receive intravenous (IV) midazolam, IV saline, or no IV access. Although the procedure was perceived “less difficult” in the IV midazolam group compared with the IV saline group, the difference was not statistically significant. The power to detect differences between the three groups was not determined in this study. The small patient population and the lack of validated criteria to assess the difficulty of an EGD limit the utility of the evidence.

The feasibility of unsedated small-caliber EGD was also assessed as part of the multiphase Mayo Clinic Rochester study of a select group of highly motivated patients and volunteers.10 The second portion of the duodenum was reached in 20 sedated and 20 unsedated volunteers in this prospective, nonrandomized study. Among the patients, 50 subjects successfully underwent sedated small-caliber EGD followed by sedated conventional EGD, and 38 of 40 patients underwent successful unsedated small-caliber EGD followed by sedated conventional EGD. Overall, the technical feasibility was not significantly affected by sedation in this study. A type II error (failure to detect a significant difference when there is a difference) cannot be ruled out, however, because the sample size to detect a significant difference was not calculated.

Investigators have also studied the feasibility of unsedated transnasal small-caliber EGD. Saeian and coworkers11 showed that unsedated transnasal esophagoscopy with a 5.3-mm gastroscope was feasible in 15 cirrhotic patients. The study was uncontrolled, and the population was very small. Zaman and colleagues13 compared peroral and transnasal approaches for EGD with the same small-caliber instrument using a prospective randomized crossover study design. Of 105 patients, 60 (57%) agreed to undergo unsedated small-caliber EGD. Peroral unsedated EGD was feasible in 34 of 35 (97%) patients, including 4 who failed transnasal EGD and were crossed over. Unsedated transnasal EGD was feasible in only 25 of 29 (86%) patients. The statistics were not reported, and a sample size based on a study hypothesis was also not calculated before study initiation.

Campo and coworkers14 randomly assigned 181 Spanish patients to undergo transnasal small-caliber EGD or peroral conventional EGD. Insertion failed in six (3.3%) patients; four had been randomly assigned to the transnasal route and two to the peroral route. In a prospective randomized trial in Australia, Craig and colleagues17 compared the feasibility of unsedated transnasal with unsedated peroral small-caliber EGD. A complete examination was feasible in 74 of the 84 (88%) transnasal and 85 of the 86 (99%) transoral procedures (P = .004).

Dumortier and coworkers18 reported that unsedated transnasal EGD was feasible in 1033 of 1100 (94%) patients studied prospectively at three French medical centers. Failures were mainly due to the inability to insert the small-caliber endoscope (62.7%). Other reasons for failure included patient refusal and nasal pain. In their prior study published in 1999, the same investigators showed that unsedated transnasal EGD was feasible in 82% of the study population and was associated with less nausea and choking.19 The feasibility of transnasal small-caliber EGD was initially assessed in 100 patients in this two-phase study; 150 patients were then randomly assigned to undergo peroral conventional EGD with a 9.8-mm videoendoscope, peroral small-caliber EGD with a 6-mm videoendoscope, or transnasal small-caliber EGD with a 6-mm videoendoscope.

Tolerability of Unsedated Small-Caliber Endoscopy

Tolerability is a complex variable, which is likely affected by numerous patient-related and operator-related factors, including patient education, prior endoscopic experience, preprocedure anxiety, patient age, patient gender, endoscopist skill, and technical performance of the endoscope. A prohibitively large and diverse patient population would be required to determine how all of these factors affect the tolerability and acceptance of unsedated endoscopy. Catanzaro and coworkers20 evaluated patient tolerability of unsedated endoscopy with a 4-mm esophagoscope. This study enrolled 51 patients; 30 patients underwent an unsedated procedure. Of these patients, 18 preferred the peroral route, and 12 preferred the transnasal route. Patient tolerability and acceptability of unsedated esophagoscopy with the 4-mm esophagoscope compared favorably with a historical group of patients examined with a 3-mm esophagoscope.

In an earlier study, Catanzaro and colleagues21 assessed the use of a 3.1-mm, battery-operated esophagoscope in an unsedated procedure. Examination with the battery-operated esophagoscope was performed in 98 patients. Of the 56 patients undergoing an unsedated examination, 43 preferred the peroral approach. Although the endoscopist’s perception of patient discomfort was not significantly different, the patients undergoing unsedated small-caliber esophagoscopy reported significantly more choking, pain, and overall discomfort with the 3.1-mm, battery-operated esophagoscope.

Faulx and coworkers22 approached 98 patients to undergo unsedated esophagoscopy with a 3.1-mm esophagoscope before conventional EGD. Only 46% of the 52 patients participating in the study preferred unsedated 3.1-mm esophagoscopy over conventional EGD in the future. Of patients, 16 chose the peroral approach, and 36 chose the transnasal approach. Patients who chose the peroral route were more likely to prefer unsedated small-caliber endoscopy with the 3.1-mm esophagoscope compared with the transnasal approach (58% vs. 23%).

Saeian and colleagues11 performed sedated conventional EGD following unsedated small-caliber EGD and reported no significant difference in choking, discomfort, and sore throat in a population of 15 cirrhotic patients. In contrast, Wilkins and coworkers6 reported increased gagging and choking in the 33 patients randomly assigned to undergo unsedated small-caliber EGD compared with the 39 patients who underwent sedated conventional EGD. However, most patients tolerated unsedated small-caliber EGD.

A prospective study in the United States found that only 52 of 98 patients (53%) approached agreed to undergo unsedated esophagoscopy with a 3.1-mm esophagoscope followed by sedated EGD.22 Although one may argue that the willingness to undergo unsedated endoscopy may be hampered by undergoing tandem endoscopies, this is one of the few well-designed studies to address the impact of unsedated endoscopy on the practice of EGD. Of the 52 patients who underwent both procedures, only 46% preferred unsedated EGD. Patients who had transnasal esophagoscopy were less likely to prefer an unsedated procedure in the future compared with patients who underwent peroral esophagoscopy (23% vs. 58%). Similarly, Zaman and colleagues23 reported that 19 (31%) of 62 patients asked to undergo unsedated 6-mm transoral EGD followed by sedated transoral conventional EGD refused. Of the 43 patients who agreed to undergo unsedated small-caliber EGD, 30 (70%) were willing to have unsedated small-caliber EGD in the future.

A prospective randomized controlled trial from a center in the United Kingdom that routinely performs unsedated endoscopies concluded that endoscopists found unsedated examinations easier, but patients reported significantly greater comfort with sedation.24 Another trial from the United Kingdom that studied 62 elderly patients reported that an equal number of patients undergoing sedated or unsedated EGD described the procedure as “mildly unpleasant.”25 Of the patients who underwent unsedated EGD, 73% did not wish to be sedated for future EGD. Froehlich and colleagues26 randomly assigned 200 European patients to receive IV midazolam with lidocaine spray, IV placebo with lidocaine spray, IV midazolam with placebo spray, or IV placebo with placebo spray and showed that tolerability, assessed on a visual analogue scale, was significantly improved in patients who received IV sedation.

One major difficulty with the interpretation of the studies comparing the tolerability of unsedated endoscopy with sedated procedures is that benzodiazepines affect recall. The timing of when the patient is questioned may affect the response to the questions. The only prospective controlled trial that compared two unsedated procedures found that patients reported less discomfort when peroral EGD was performed with a 6-mm endoscope compared with a 9.8-mm instrument.7 Sedation during future examination was requested by 14% of subjects who underwent examination with a 6-mm endoscope compared with 31% of patients examined with a 9.8-mm endoscope.

A few studies have compared the tolerability and acceptance of unsedated transnasal and peroral approaches. In a randomized U.S. trial of unsedated peroral versus transnasal small-caliber EGD, Zaman and coworkers13 determined that 89% of the patients undergoing peroral EGD and 69% of the patients undergoing transnasal EGD were willing to have unsedated small-caliber EGD in the future. A smaller U.S. study of 24 patients who had undergone transnasal unsedated EGD followed by conventional EGD concluded that transnasal EGD was more acceptable.15 However, a randomized Australian study of 170 patients found no significant difference in tolerability of unsedated small-caliber EGD with either route.17 Dumortier and colleagues18 reported that 95% of 1033 French patients who successfully underwent unsedated small-caliber transnasal EGD were willing to repeat the procedure. Of the 377 patients who had previously undergone unsedated transoral EGD, 91% preferred the transnasal route.

Safety of Unsedated Small-Caliber Endoscopy

One of the arguments for advocating unsedated procedures is that the morbidity and mortality of endoscopic procedures are largely related to sedation. The evidence to support this allegation is limited, however. The practice of sedated endoscopy is very safe, and complications are uncommon. The incidence of serious cardiorespiratory complications in an American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE)/U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) collaborative study of 21,011 procedures was 5.4 per 1000 cases, and the incidence of death was 0.3 per 1000 cases.27 A large retrospective German study found that the overall complication rate associated with sedated EGD was 0.009%.28

Because of the low complication rate of sedated EGD, any study to determine whether unsedated EGD is safer would require an extremely large patient population. The safety of unsedated EGD has been addressed in several small studies. Limited studies have reported no serious complications in 60 patients5 and 170 patients17 who underwent unsedated procedures. Epistaxis is unique to transnasal EGD and can occur in one of five patients29; this is not surprising given that insertion of a soft small-bore nasogastric tube may result in epistaxis. The largest prospective study of unsedated transnasal EGD revealed epistaxis in 2.3%, nasal pain in 1.6%, and vasovagal reactions in 0.3% of 1100 consecutive patients participating in the study at three French centers. Much larger studies of unsedated EGD are needed to determine a true cardiorespiratory complication rate of the procedure. Cost prohibits the performance of such a large prospective randomized comparative study on the safety of unsedated and sedated EGD. Although it seems that transnasal unsedated EGD is associated with an increased rate of minor complications (epistaxis) compared with peroral EGD, larger comparative studies with ultrathin endoscopes are required. In the absence of data from large prospective studies, the currently available safety data originate from small prospective or retrospective studies.

Adequacy of Unsedated Small-Caliber Endoscopy and Biopsy

The data on the adequacy of examinations performed using small-caliber endoscopes are even more limited. Image quality, suctioning ability, adequacy of tissue sampling, and ability to perform therapeutic maneuvers are among the main determinants of “adequacy.” The specifications of several small-caliber upper endoscopes are listed in Table 10.1. Most commercially available small-caliber endoscopes incorporate video charge-coupled devices technology, although some studies have been performed with fiberoptic instruments. The outside diameter of these endoscopes is 5 to 6 mm, approximately half the diameter of a conventional upper endoscope (see Fig. 10.2A). The esophagoscopes have a working length of 600 mm to allow intubation of the stomach. Some are battery-operated, and none allow biopsies. A thinner insertion tube may be too flexible, limiting passage through the pylorus and intubation of the second portion of the duodenum. Some manufacturers have marketed small-caliber endoscopes that have only unidirectional up-and-down tip deflection (see Fig. 10.2B), whereas others have bidirectional up-and-down and right-and-left tip deflection similar to conventional instruments. The accessory channel of small-caliber esophagogastroduodenoscopes is generally 2 mm; this limits the size of the biopsy specimens that can be obtained and the ability to perform therapeutic interventions. The smaller diameter of the channels could also impair the ability to aspirate blood, secretions, and debris and the ability to wash the lens. A sample image of the gastroesophageal junction as viewed by a small-caliber endoscope is shown in Fig. 10.4, and a brief normal transnasal examination is presented as a video clip.![]()

Fig. 10.4 Endoscopic image of a normal squamocolumnar junction as viewed by a videoesophagogastroduodenoscope.

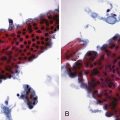

Wildi and coworkers30 and Catanzaro and colleagues20,21 addressed the accuracy of small-caliber esophagoscopes. Wildi and coworkers30 assessed the diagnostic accuracy of sedated esophagoscopy performed by a nurse practitioner using a 4-mm esophagoscope compared with sedated conventional EGD performed by an experienced gastroenterologist. There were 40 patients who underwent tandem procedures in a blinded fashion. For all esophageal lesions, the sensitivity and specificity of the examination by the nurse practitioner were 75% and 98%. All four Schatzki rings were missed.30 In their study of 51 patients undergoing esophagoscopy using the 4-mm esophagoscope, Catanzaro and colleagues20 reported sensitivity, accuracy, and specificity of 91%, 98%, and 99% for detecting all esophageal lesions. The first 24 patients underwent endoscopy using the battery-operated fiberoptic esophagoscope, and 27 patients were examined with the 4-mm videoesophagoscope. In an earlier study, Catanzaro and coworkers21 reported that the accuracy of esophageal examination with a 3.1-mm endoscope is substantially inferior to conventional EGD. The sensitivity for detecting Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal tumors, and esophageal varices was 54.5%, 66.7%, and 80%. Optical quality was reported as less than 4 on a scale of 1 to 5 in 42% of the cases.

In the study of Dumortier and colleagues,18 endoscopic biopsy specimens, obtained in 457 subjects undergoing a transnasal examination, were considered “sufficient.” Four esophageal cancers and one gastric cancer were correctly diagnosed by biopsy. Although this is the largest study addressing the adequacy of samples obtained at the time of unsedated transnasal EGD, this outcome was not the primary or even secondary goal of the study. Criteria for determining sample adequacy were not defined. Zaman and coworkers18 reported that unsedated peroral small-caliber EGD with a video instrument missed 5 of 59 lesions identified by conventional EGD in 62 patients, yielding an accuracy of 92%. The optical quality of the images was rated as good in 84%, 65%, and 78% of the subjects when examining the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. In a similar study of unsedated transnasal EGD, Dean and colleagues15 found a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 97% using a fiberoptic instrument.

In the only study examining the effect of sedation and endoscope caliber, Sorbi and coworkers10 showed that the accuracy for major endoscopic findings was 96% for the 50 patients who underwent sedated transoral small-caliber EGD and 97% for the 40 patients who underwent unsedated transoral small-caliber EGD. The view was particularly limited because of the inability to aspirate secretions and clear bubbles rapidly. These results suggest that caliber, and not sedation, may be the primary factor determining the accuracy of unsedated small-caliber endoscopy. The 4-mm diameter may be the lower limit for upper endoscopes to maintain adequate image quality.

Cost-Effectiveness of Unsedated Small-Caliber Endoscopy

Cost may be the major impetus behind the practice of unsedated endoscopy. Elimination of sedation may significantly reduce the cost of endoscopy. However, the total expense of unsedated endoscopy must be studied in view of its impact on the everyday practice of EGD. Unsedated small-caliber endoscopy can result in savings only if the general population finds it acceptable and if most unsedated examinations are adequate and a repeat examination under sedation is not required. The impact of unsedated endoscopy on the cost of EGD has been evaluated only in a few studies. In a case-control study, Gorelick and colleagues31 assessed the potential cost savings associated with unsedated small-caliber EGD in 16 patients undergoing unsedated transoral small-caliber EGD matched for age, gender, indication, and procedure day with a control group of 16 patients who underwent sedated conventional EGD. The mean procedure room time was 16.3 minutes for unsedated small-caliber EGD and 34.9 minutes for sedated conventional EGD (P < .0005). The mean recovery room time was 9.0 minutes for unsedated small-caliber EGD and 41.3 minutes for sedated conventional EGD (P < .00001). The mean cost for unsedated small-caliber EGD was $462 and was considerably lower than the mean cost of sedated conventional EGD, which was reported as $587 (P < .0006).

In a controlled study, Wilkins and coworkers6 randomly assigned 72 patients to undergo either unsedated small-caliber EGD or sedated conventional EGD. The procedure time (mean ± standard error of the mean) for the 33 patients who underwent unsedated small-caliber EGD was 21.5 ± 2.3 minutes, whereas the procedure time for the 39 patients who underwent sedated conventional EGD was 55.4 ± 2.3 minutes. Without performing a formal cost analysis, the investigators suggested that unsedated small-caliber EGD performed by primary care physicians could increase access while decreasing the cost of upper endoscopy. Bampton and colleagues32 compared unsedated transnasal EGD with sedated transoral EGD. The mean procedure times of 15 minutes for the unsedated procedure and 20 minutes for the sedated procedure were not significantly different. However, the mean recovery time was 7 minutes for the unsedated transnasal examination compared with 37 minutes for the transoral sedated EGD, emphasizing the shorter recovery time when no sedation is administered. A formal cost-effectiveness analysis of unsedated versus sedated endoscopy that accounts for variations in the patient population, patient acceptance, completion rates, and diagnostic accuracy is yet to be performed to determine the utility of this approach in the daily practice of upper endoscopy.

Therapeutic Applications for Small-Caliber Endoscopy

The following are common and practical applications:

1 Wildi S, Gubler C, Vavricka S, et al. Transnasal endoscopy for the placement of nasoenteral feeding tubes: does the working length of the endoscope matter? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:225-229.

2 Adler D, Gostou C, Baron T. Percutaneous transgastric placement of jejunal feeding tubes with an ultrathin endoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;55:106-110.

3 DiSario J, Baskin W, Brown R, et al. Endoscopic approaches to enteral nutritional support. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:901-908.

4 Al-Haddad M, Pungpapong S, Wallace M, et al. Antegrade and retrograde endoscopic approach in the establishment of a neo-esophagus: a novel technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:290-294.

5 Maple J, Petersen B, Baron T, et al. Endoscopic management of radiation-induced complete upper esophageal obstruction with an antegrade-retrograde rendezvous technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:822-828.

6 Wilkins T, Brewster A, Lammers J. Comparison of thin versus standard esophagogastroduodenoscopy. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:625-629.

7 Mulcahy HE, Riches A, Kiely M, et al. A prospective controlled trial of an ultrathin versus a conventional endoscope in unsedated upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2001;33:311-316.

8 Mulcahy HE, Kelly P, Banks MR, et al. Factors associated with tolerance to, and discomfort with, unsedated diagnostic gastroscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:1352-1357.

9 Ristikankare M, Hartikainen J, Heikkinen M, et al. Is routinely given conscious sedation of benefit during colonoscopy? Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:566-572.

10 Sorbi D, Gostout CJ, Henry J, et al. Unsedated small-caliber esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) versus conventional EGD: A comparative study. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1301-1307.

11 Saeian K, Staff D, Knox J, et al. Unsedated transnasal endoscopy: a new technique for accurately detecting and grading esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2246-2249.

12 Shaker R, Saeian K. Unsedated transnasal laryngo-esophagogastroduodenoscopy: an alternative to conventional endoscopy. Am J Med. 2001;111(Suppl 8A):153S-156S.

13 Zaman A, Hahn M, Hapke R, et al. A randomized trial of peroral versus transnasal unsedated endoscopy using an ultrathin videoendoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49(3 Pt 1):279-284.

14 Campo R, Montserrat A, Brullet E. Transnasal gastroscopy compared to conventional gastroscopy: A randomized study of feasibility, safety, and tolerance. Endoscopy. 1998;30:448-452.

15 Dean R, Dua K, Massey B, et al. A comparative study of unsedated transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy and conventional EGD. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:422-424.

16 Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Daniel E, et al. Transnasal esophagoscopy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:588-589.

17 Craig A, Hanlon J, Dent J, et al. A comparison of transnasal and transoral endoscopy with small-diameter endoscopes in unsedated patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:292-296.

18 Dumortier J, Napoleon B, Hedelius F, et al. Unsedated transnasal EGD in daily practice: results with 1100 consecutive patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:198-204.

19 Dumortier J, Ponchon T, Scoazec JY, et al. Prospective evaluation of transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy: Feasibility and study on performance and tolerance. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49(3 Pt 1):285-291.

20 Catanzaro A, Faulx A, Isenberg GA, et al. Prospective evaluation of 4-mm diameter endoscopes for esophagoscopy in sedated and unsedated patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:300-304.

21 Catanzaro A, Faulx A, Pfau PR, et al. Accuracy of a narrow-diameter battery-powered endoscope in sedated and unsedated patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:484-487.

22 Faulx AL, Catanzaro A, Zyzanski S, et al. Patient tolerance and acceptance of unsedated ultrathin esophagoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:620-623.

23 Zaman A, Hapke R, Sahagun G, et al. Unsedated peroral endoscopy with a video ultrathin endoscope: patient acceptance, tolerance, and diagnostic accuracy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1260-1263.

24 Fisher NC, Bailey S, Gibson JA. A prospective, randomized controlled trial of sedation vs. no sedation in outpatient diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Endoscopy. 1998;30:21-24.

25 Solomon SA, Kajla VK, Banerjee AK. Can the elderly tolerate endoscopy without sedation? J R Coll Physicians Lond. 1994;28:407-410.

26 Froehlich F, Schwizer W, Thorens J, et al. Conscious sedation for gastroscopy: Patient tolerance and cardiorespiratory parameters. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:697-704.

27 Arrowsmith JB, Gerstman BB, Fleischer DE, et al. Results from the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy/U.S. Food and Drug Administration collaborative study on complication rates and drug use during gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:421-427.

28 Sieg A, Hachmoeller-Eisenbach U, Heisenbach T. [How safe is premedication in ambulatory endoscopy in Germany? A prospective study in gastroenterology specialty practices]. Deutsche Med Wochenschr. 2000;125:1288-1293.

29 Zuccaro GJr. Sedation and sedationless endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2000;10:1-20. v

30 Wildi SM, Wallace MB, Glenn TF, et al. Accuracy of esophagoscopy performed by a non-physician endoscopist with a 4-mm diameter battery-operated endoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:305-310.

31 Gorelick AB, Inadomi JM, Barnett JL. Unsedated small-caliber esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD): less expensive and less time-consuming than conventional EGD. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:210-214.

32 Bampton PA, Reid DP, Johnson RD, et al. A comparison of transnasal and transoral oesophagogastroduodenoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:579-584.

33 Chen Y, Nichols M, Antillon M, et al. Peroral cholecystoscopy with electrohydraulic lithotripsy for treatment of symptomatic cholelithiasis in end-stage liver disease (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:132-135.