CHAPTER 28 Sleeve gastrectomy

Step 1. Surgical anatomy

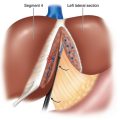

♦ The stomach has a rich blood supply, which includes the left and right gastric arteries, the left and right gastroepiploic arteries, and the short gastric vessels. This operation involves removal of the majority of the stomach, leaving behind a narrow “sleeve” of stomach based along the lesser curvature, with vascularization essentially derived from the left gastric artery. The vagus nerves on the lesser curve of the stomach are left intact.

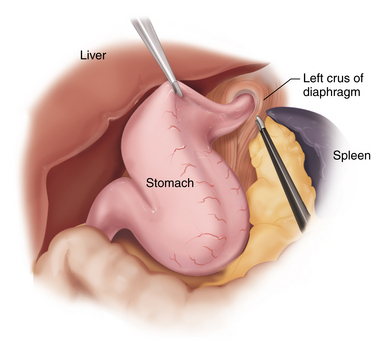

♦ Special consideration is given at the angle of His to ensure the entire left diaphragmatic crus is freed from attachments, such that transection of the stomach does not leave a posterior pouch of fundus on the proximal portion of the sleeve. Reduction of hiatal hernia may be necessary to ensure complete removal of redundant fundus.

Step 2. Preoperative considerations

Patient preparation

♦ Sleeve gastrectomy may be performed on those patients who qualify for bariatric surgery (i.e., meet National Institutes of Health (NIH) criteria and have satisfied a multidisciplinary evaluation by a weight-loss surgery team). This operation has been generally offered as an “initial stage” in patients who are at high risk for other more traditional bariatric operations. Sleeve gastrectomy is considered for the following high-risk patients:

Patients with cirrhosis or esophageal/gastric varices (severe hepatic disease may preclude all types of weight loss surgery)

Patients with cirrhosis or esophageal/gastric varices (severe hepatic disease may preclude all types of weight loss surgery)♦ After significant weight loss, these patients may undergo a “second-stage” operation with conversion to either Roux-en-Y gastric bypass or biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. With excellent initial weight loss results and increasing experience with the operation, many groups are now offering it as a stand-alone procedure in average-risk patients.

♦ Special attention in the history and physical should elicit any signs of liver disease and cirrhosis. In diabetic patients, if there is a clinical suspicion of gastroparesis, gastric emptying studies should be considered. Preoperative upper endoscopy should be performed to diagnose hiatal hernia and rule out gastric lesions or helicobacter pylori infection.

Equipment and instrumentation

♦ Standard laparoscopic instruments are used throughout the case. Depending on the type of stapler used, 15-mm disposable trocars may be necessary. We commonly use a buttress material on the stapler cartridges to aid in hemostasis. Either ultrasonic energy or LigaSure (Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts) can be used for division of the vascular attachments.

Patient positioning

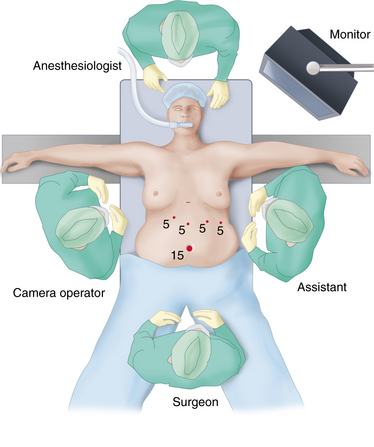

♦ The patient is best positioned supine with both arms abducted and the legs split. The surgeon stands between the legs with an assistant holding the camera on the patient’s right and an additional assistant on the left.

♦ The patient is placed in reverse Trendelenburg position throughout the procedure.

Step 3. Operative steps

Access and port placement

♦ Pneumoperitoneum can be established via a variety of time-honored techniques.

♦ Trocars are placed as follows: a 15-mm trocar at the umbilicus, a 5-mm trocar in the right upper quadrant, 5-mm trocar in the epigastrium, a 5-mm trocar in the left upper quadrant, and a 5-mm trocar in the lateral left upper quadrant. The Nathanson liver retractor is placed via an additional 5-mm incision in the high-epigastrium. Alternatively, trocars can be placed in the right and left upper quadrant for use in stapling (Figure 28-1).

Operative steps

♦ The gastrocolic omentum is divided off the greater curvature of the stomach, beginning approximately 5 cm proximal to the pylorus and proceeding to the angle of His. The entire fundus is freed posteriorly from the left crus. Posterior attachments to the pancreas are also divided such that the stomach is only attached via its lesser curvature blood supply (Figure 28-2).

♦ If present, a hiatal hernia should be reduced. A large gastric fat pad can be resected.

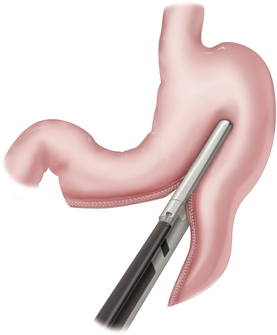

♦ Transection of the stomach begins on the antrum 5 cm proximal to the pylorus with a 60-mm long, 4.8-mm articulating stapler. The 4.8-mm stapler can be used for the entire resection with the addition of commercially available buttress materials. Alternatively, staples that are 3.5 mm in height can be used in the thinner, more proximal portions of the stomach.

♦ The transection is oriented along the lesser curvature such that the stomach is not narrowed at the incisura (Figure 28-3).

♦ After two staple firings, a 40 F bougie is placed by the anesthesia team and directed toward the pylorus along the lesser curvature. The remainder of the stomach transection is performed while pushing the bougie against the lesser curvature to guide the resection as it proceeds toward the angle of His.

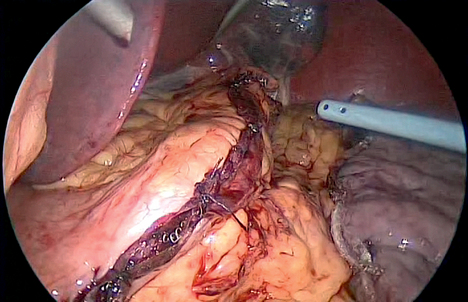

♦ The staple line is closely inspected, and portions may be oversewn to ensure hemostasis as necessary.

♦ A methylene blue leak test is performed. The distal stomach is occluded with a bowel grasper while approximately 60 cc of methylene blue is instilled under gentle pressure created with a bulb syringe. The entire staple line is checked not only for leaks but for proper formation of the staples, particularly around the thick antrum (Figure 28-4).

♦ The specimen is removed using a bag via the 15-mm umbilical trocar. The umbilical port can be stretched with a large clamp prior to extraction. The incision generally does not need to be lengthened significantly if the stomach specimen is placed in the bag with the distal (antral) portion of the staple line protruding out. This enables the staple line to be grasped and the stomach delivered from the bag, rather than blindly grabbing the larger fundic portion.

Step 4. Postoperative care

♦ Patients are monitored in an appropriate setting before transfer to the floor.

♦ An upper gastrointestinal series may be obtained on the first postoperative day to exclude leaks and evaluate gastric function and anatomy (Figure 28-5).

♦ Diet is liquids on the first day, and it progresses to pureed food on the second day. Patients are usually discharged home on the second postoperative day.

Step 5. Pearls and pitfalls

♦ Staple the antrum with caution, as this tissue may be relatively thick and could cause stapler misfire or fracturing of the tissue. If staple line reinforcement products are used, it may be prudent to forego them in the antral area.

♦ It is extremely important to have the anesthesiologist hold the bougie in place throughout the entire resection of the stomach. Failure to do so may result in an unnoticed withdrawal of the bougie away from the lesser curvature and inadvertent transection of the bougie or the stomach.

♦ The final staple firing should veer away from the gastroesophageal junction so that the esophagus is avoided. The thinner esophageal wall and absence of serosa make it vulnerable to inadequate stapler closure, which may contribute to leak formation.

♦ Carefully inspect the entire gastric staple line upon completion to ensure all staples are well formed and oversew portions as necessary, especially at the junction of stapler firings.

♦ Patients may experience significant reflux, nausea, and dysphagia, which can be managed with appropriate medications postoperatively.

Moy J, Pomp A, Dakin G, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity. Am J Surg. 2008;196(5):e56-e59.

Lee CM, Cirangle PT, Jossart GH. Vertical gastrectomy for morbid obesity in 216 patients: report of two-year results. Surg Endosc. 2007;21;10:1810-1816.

Lalor PF, Tucker ON, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Complications after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(1):33-38.

Parikh M, Gagner M, Heacock L, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: does bougie size affect mean %EWL? Short-term outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4;4:528-533.