Chapter 17 Sleep Disorders

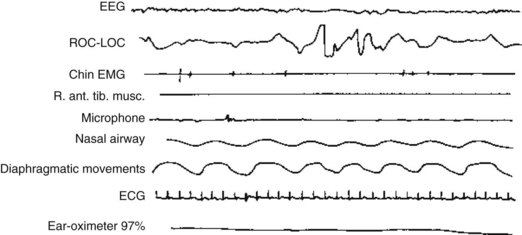

In sleeping individuals, the PSG simultaneously records:

• Cerebral activity through several electroencephalogram (EEG) channels

• Ocular movements through bilateral ocular channels (ROC and LOC)

• Chin, limb, or other muscle movement and tone through an electromyogram (EMG)

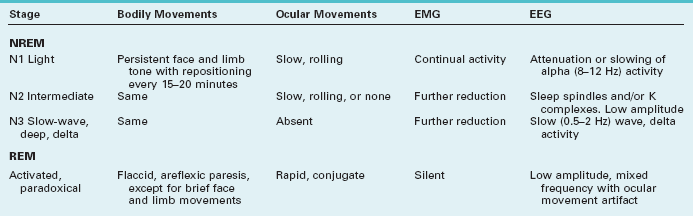

PSG studies readily distinguish two phases of sleep. A rapid eye movement (REM) phase consists of dream-filled sleep accompanied by brisk, conjugate, and predominantly horizontal rapid conjugate eye movements and flaccid limb paralysis. A nonrapid eye movement (NREM) phase consists of relatively long stretches of essentially dreamless sleep accompanied, approximately every 15 minutes, by repositioning movements of the body (Table 17-1).

Normal Sleep

REM Sleep

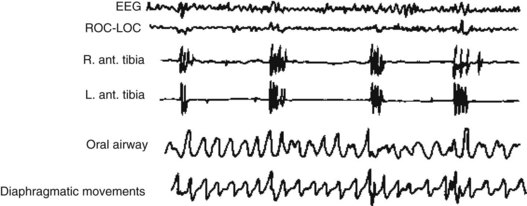

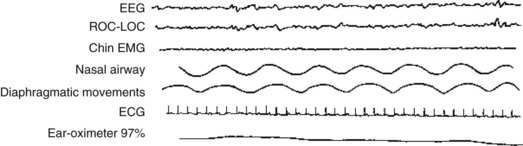

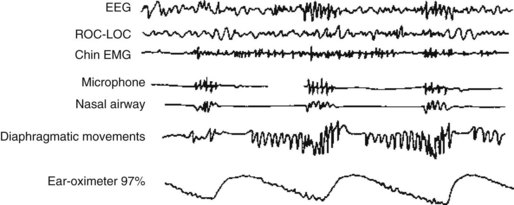

Except for the eye movements and normal breathing, people in REM sleep remain immobile with paretic, flaccid, and areflexic muscles. EMGs recorded from chin and limb muscles, which are a standard placement, show no electric activity (Fig. 17-1). This paralysis is fortuitous because it prevents people from acting out their dreams.

FIGURE 17-1 Polysomnography of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep displays nine channels, each of which monitors a physiologic function. The EEG has low-voltage, fast activity similar to the EEG activity of awake individuals. The electro-oculogram (EOG) channel – ROC-LOC – reflects several REMs by large-scale, quick fluctuations. Electromyograms (EMGs) of the chin and right anterior tibialis muscles show virtually no activity, which indicates an absence of muscle movement and tone (flaccid paresis). The microphone detects a snore. The regular, undulating airway and diaphragm recordings indicate normal breathing and air movement.

Nuclei in the pons generate the basic physical elements of REM sleep, and the peri-locus ceruleus, situated immediately adjacent to locus ceruleus, abolishes muscle tone (see Chapters 18 and 21). In other words, an active process, rather than simply relaxation, produces REM sleep’s characteristic paresis as well as the characteristic ocular movement.

NREM Sleep

Other distinguishing features of NREM sleep relate to the motor system. Individuals in NREM sleep have conspicuous repositioning movements of their body, relatively normal muscle tone, and preserved deep tendon reflexes. Their chin and limb muscles display readily detectable EMG activity (Fig. 17-2).

FIGURE 17-2 The polysomnogram of N1 stage sleep, which neurologists previously called stage l nonrapid eye movement sleep, shows low-voltage, 7-Hz activity. The ROC-LOC channel shows occasional slow ocular movement (i.e., no rapid eye movement activity). The chin electromyogram shows continual low-voltage activity that reflects persistent muscle tone.

Patterns

During daytime, sleep latency shrinks to its shortest duration during the afternoon, at approximately 4:00 PM. However, numerous psychologic and physical factors may alter it. In fact, short sleep latencies characterize several sleep disorders (Box 17-1).

Once asleep, normal individuals enter NREM sleep and pass in succession through its three stages. After 90–120 minutes of NREM sleep, they enter the initial REM period. Abnormalities in the interval between falling asleep to the first REM period, the REM latency, characterize several sleep disorders, particularly narcolepsy (Box 17-2).

Box 17-2

Shortened or Sleep-Onset Rapid Eye Movement (REM) Latency*

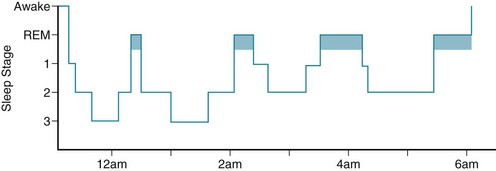

The NREM–REM cycle repeats throughout the night with a periodicity of approximately 90 minutes. REM periods develop four or five times in total, but in the latter half of the night, they lengthen and occur more frequently (Fig. 17-3). Also, in the latter half, when the tendency toward REM sleep peaks, body temperature falls to its lowest point (the nadir). The final REM period typically merges with awakening. Consequently, people can most easily recall their final dream, which may incorporate surrounding morning household activities. In addition, because of residual REM influence, men’s erections often persist on awakening.

FIGURE 17-3 In the conventional representation of a normal night’s sleep pattern – its sleep architecture or hypnogram – the first rapid eye movement (REM) period starts approximately 90 minutes after sleep begins and lasts about 10 minutes. Later in the night, REM periods recur more frequently and have longer duration. Nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep progresses through its three stages (N1–N3).

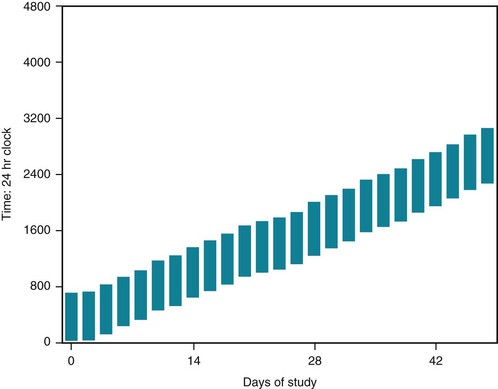

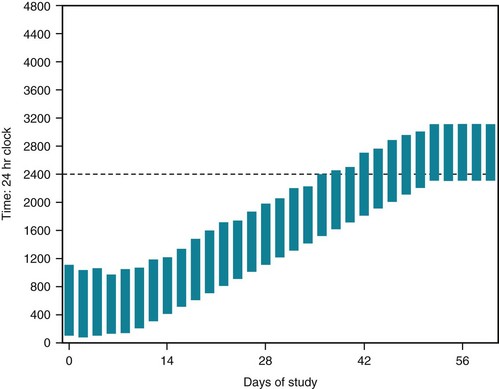

Without external clues, an “internal biological clock,” centered in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus, would set the daily (circadian) sleep–wake cycle at 24.5–25 hours (Fig. 17-4). This nucleus also sets the circadian hormone and metabolic rhythms. When individuals are forced to rely exclusively on their internal biologic clock, as when they volunteer for experiments that isolate them from their environment and its cues, such as living in caves for months, they gradually lengthen their circadian cycle to almost 25 hours and fall asleep later each day.

FIGURE 17-4 When healthy young adults are allowed to sleep and arise at will in rooms protected from time cues, such as clocks, daylight, daytime sounds, and delivery of meals on a fixed schedule, i.e., “free run,” they typically go to sleep later each day (delay their sleep phase) and extend their sleep–wake (circadian) cycle to 24.5– 25 hours, as shown here.

Melatonin

The pineal gland synthesizes melatonin, which is an indolamine, through the following pathway:

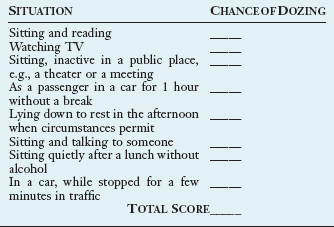

Sleep Deprivation

Although various sleep disorders often result in excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), sleep deprivation from social and vocation pressures is, by far, the most common cause of EDS. In quantifying sleepiness, physicians often utilize the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (Box 17-3).

Sleep Disorders

The preliminary version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5) lists Sleep–Wake Disorders primarily on the basis of their PSG and other physiologic parameters (Box 17-4). Neurologists follow a more streamlined and better-organized three-category classification, which this book presents: dyssomnias, parasomnias, and medical or psychiatric conditions that produce sleep disorders. Both classifications, which have consistent criteria for the disorders, allow physicians to attribute abnormal sleep-related behavior and thinking to objective, measurable, and reproducible physiologic disturbances.

Dyssomnias

Intrinsic Sleep Disorders

Narcolepsy

• Hallucinations on falling asleep (hypnagogic hallucinations) or during sleep (sleep-related hallucinations).

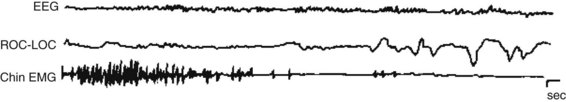

During hypnopompic or hypnagogic hallucinations, patients essentially experience vivid dreams while in a twilight state, but they are technically awake. Hypnopompic or hypnagogic hallucinations qualify as an organic cause of visual hallucinations (see Chapters 9 and 12). As with the other features of narcolepsy, hypnopompic or hypnagogic hallucinations represent REM sleep intruding into people’s wakefulness or at least the transition into wakefulness (Fig. 17-5).

FIGURE 17-5 A narcoleptic attack begins when the electroencephalogram channel shows the low-voltage fast activity of rapid eye movement sleep. The absence of chin electromyogram activity indicates that muscles are flaccid. After several seconds, REMs begin.

Despite their help in counteracting narcolepsy and keeping patients awake, these medicines have little effect on cataplexy. Instead, a rapid-acting hypnotic, oxybate (Xyrem), also known as gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) or the “date rape drug,” reduces cataplexy. In addition, it increases slow-wave sleep. Illicitly prepared oxybate has caused many complications, including profound amnesia, coma, seizures, and, with continued use, addiction (see Chapter 21). Even a pharmaceutical preparation in narcolepsy-cataplexy patients may lead to sleepwalking, enuresis, confusion, and sleepiness. It may also lead to depression in predisposed patients. However, it does not seem to lead to addiction or, on stopping it, rebound insomnia.

Sleep-Disordered Breathing (Sleep Apnea)

The central variety, which is less common, results from reduced or inconsistent CNS ventilatory effort or congestive heart failure. Patients who have survived lateral medullary infarctions and other injuries to the medulla (see Chapter 2), which houses the respiratory drive center, are susceptible to central sleep apnea.

In both children and adults, the combination of EDS and snoring is the classic indication for performing a PSG. In sleep apnea, the PSG shows periods of apnea, arousals, and hypoxia. It detects intermittent loss of air flow despite chest and diaphragm respiratory movements and episodic loud snoring (Fig. 17-6). Because of sleep deprivation, sleep latency and REM latency both shorten and SOREMPs appear. During nighttime sleep, apnea episodes occur in either phase but more frequently during REM sleep because that sleep phase reduces muscle tone.

FIGURE 17-6 In sleep apnea, the polysomnogram shows that oxygen saturation falls during a period of nonrapid eye movement sleep. Hypoxia then triggers a partial arousal, indicated by faster electroencephalogram activity. Diaphragmatic movements reach a crescendo and loud snoring begins. After strenuous diaphragm movements, air moves through the nasal airway and oxygen saturation improves.

Restless Legs Syndrome

An observation that many otherwise healthy individuals with RLS have close relatives with the same problem indicated that RLS has a genetic basis or susceptibility. Indeed, genetic studies revealed a mutation on chromosome 6 in many patients. Studies of D2 receptor binding in the striatum (see Chapter 18) have yielded contradictory results. However, decreased D2 binding in some of them is consistent with a successful therapeutic strategy (see later).

Periodic Limb Movement Disorder

Movements take place at 20–40-second intervals, for episodes of 10 minutes to several hours primarily, but not exclusively, during stages of NREM sleep (Fig. 17-7). Periodic limb movements generally do not arouse patients. Thus, the movements rarely lead to EDS.

Extrinsic Sleep Disorders

Caffeine

Caffeine, the world’s most commonly used stimulant, is a major ingredient in coffee, tea, and soft drinks; chocolate and other foodstuffs; and over-the-counter medicines (Table 17-2). It most likely combats sleepiness by acting as an antagonist to adenosine (see before).

TABLE 17-2 Caffeine Content of Popular Beverages, Medicines, and Foods

| Coffees* | |

| Brewed | |

| Generic | 80–175 |

| Decaffeinated | 2–4 |

| Dunkin’ Donuts | 143 |

| Espresso† | 100 |

| General Foods | |

| Café Vienna | 90 |

| Swiss Mocha | 55 |

| Instant, generic | 60 |

| Starbucks, Grande (16 oz) | 330 |

| Teas | |

| Lipton | |

| Brewed | 40 |

| Peppermint | 0 |

| Celestial Seasonings | |

| Ginseng | 50 |

| Herbal | 0 |

| Generic | |

| Black | 45 |

| Green | 20 |

| White | 15 |

| Green tea | 30 |

| Snapple | |

| Black | 14 |

| Lemon, peach | 21 |

| Sweet | 8 |

| Mistic Lemon | 12 |

| Nesta Lemon Sweet | 11 |

| Soft Drinks | |

| 7-Up | |

| Regular | 0 |

| Diet | 0 |

| AMP Energy Drink | 71 |

| Cocoa | 2–20 |

| Coca-Cola | |

| Classic 12 oz | 35 |

| Diet 12 oz | 47 |

| Dr. Pepper | 28 |

| Jolt | 72 |

| Mountain Dew 12 oz | 55 |

| Pepsi-Cola | 25 |

| Sprite | |

| Regular | 0 |

| Diet | 0 |

| Medicines | |

| Anacin 2 tablets | 64 |

| Coryban-D Cold | 30 |

| Excedrin 2 tablets | 130 |

| NoDoz 1 tablet max. | 200 |

| Vivarin 1 tablet | 200 |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Ben & Jerry’s Coffee Frozen Yogurt | 85 |

| Chocolate‡ | |

| Dark | 20 |

| Milk | 6 |

| Chocolate cake | 20–30 |

| Starbucks coffee | |

| Icecream | 40–60 |

*For coffees and teas, caffeine content varies by the type of bean or leaf, preparation, and duration of brewing as well as by the size of the serving.

Circadian Rhythm Disorders

Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome

Chronotherapy delays patients’ sleep phase by 1–3 hours successively each night. Using activities, coffee, sunlight, or strong artificial light, this strategy eventually postpones (delays) the sleep onset time by almost 24 hours. Patients eventually fall asleep at a conventional time, such as 11 PM, and, with effort, maintain that schedule (Fig. 17-8). Once patients reach a conventional schedule, taking melatonin at bedtime helps them maintain it.

FIGURE 17-8 A 17-year-old high-school student who has the delayed sleep phase syndrome does not fall asleep before 1:00 AM or arise before 9:00 AM. He has been unable to attend school on a regular basis and has gathered friends who have no curfews. Brought into a sleep laboratory, his sleep graph demonstrates a delayed sleep phase during the first week of study. Then each succeeding night, the staff encourage him to remain awake for an additional 30 minutes. By the end of 6 weeks, the staff have postponed (delayed) his sleep time to 2300 hours (11:00 PM) and his awakening time to 8:00 AM. For the next week, the staff reinforce the 11:00 PM to 8:00 AM schedule. The young man holds to this schedule for many months. This strategy, chronotherapy, did not require hypnotics, stimulants, or other medication; a sleep laboratory; or trained personnel.

Advanced Sleep Phase Syndrome

In the advanced sleep phase syndrome, the less frequently occurring counterpart of the delayed sleep phase syndrome, patients awake and fall asleep earlier than normal times. Their sleep, which follows an unconventional schedule, is nevertheless restful and its hypnogram displays the normal architecture (see Fig. 17-3). Individuals self-entrained to follow this schedule go to sleep, for example, at 8 PM and awaken at 5 AM. Some individuals accommodate their propensity to this schedule by seeking work in occupations that require full early-morning activity, such as living in California and following the New York Stock Exchange. Many normal older individuals who awake early in the morning have this variation. However, depressed individuals who sleep and awake early also have an advanced sleep phase syndrome.

Parasomnias

Arousal Disorders

Sleepwalking

On the basis of only the parents’ description, partial complex seizures, especially nocturnal frontal lobe seizures (see Chapter 10), may vaguely mimic sleepwalking or sleep terrors. However, seizures are stereotyped, not precipitated by arousals, prone to secondary generalization, and are often followed by (postictal) confusion. In any case, PSG supplemented by EEG-video monitoring can distinguish sleepwalking and other parasomnias from seizures. Indications for PSG with parasomnias include frequent episodes, adult onset, and potentially dangerous behavior, as well as suspicion of partial complex seizures.

Sleep Terrors

As with other parasomnias, sleep terrors usually develop within several hours after bedtime and particularly after sleep deprivation. PSG studies show that they arise in slow-wave rather than REM sleep. Noises or other disruptions during slow-wave sleep arouse children and precipitate episodes. In contrast, frightening events of the day may cause nightmares, which, like other dreams, occur during REM instead of NREM sleep (Table 17-3). The preliminary version of the DSM-5 has a similar definition for Sleep Terrors, as for Confusional Arousals and Sleepwalking.

| Sleep Terrors* | Nightmares | |

|---|---|---|

| Trigger | Partial awakening from deep sleep | Anxiety, fear |

| Onset | Early in night | Any time during night |

| Sleep stage | N3 (slow-wave sleep) | REM |

| Verbalization | Crying, screaming | Speaking words, conversing |

| Autonomic discharge | Marked | Little or none |

| Behavior after episode | Returns to deep sleep without recall | Awakens, recalls dream content, fearfulness |

REM, rapid eye movement.

REM Parasomnias

REM Sleep Behavior Disorder

REM sleep behavior disorder often develops along with or up to 15 years before the onset of either Parkinson disease or dementia with Lewy bodies. It ultimately affects almost one-third of Parkinson disease patients. In both of these illnesses, which neurologists classify as synucleinopathies (see Chapters 7 and 18), REM sleep behavior disorder correlates with cognitive impairment.

Psychiatric Disorders

Neurologic Disorders

Dementia

Dementia from Alzheimer disease and related disorders (see Chapter 7), at least in their moderate stages, disrupts patients’ sleep–wake cycle and produces nighttime thought and behavioral disturbances. During the night, patients tend toward confusion, agitation, and disorientation, especially when brought to new surroundings.

Parkinson Disease

During sleep, Parkinson disease tremor (see Chapter 18) characteristically disappears; however, the disease or medications treating it – dopamine agonists and L-dopa – frequently cause frightening vivid dreams, thought disorders, hallucinations, and agitation. Parkinson disease itself induces REM sleep behavior disorder; sleeping during the day and remaining awake at night (sleep reversal); fragmented sleep; and insomnia or hypersomnia. Dopamine agonists, more so than L-dopa, may cause episodes of irresistible sleep (sleep attacks) that interrupt activities and preclude driving. When depression complicates Parkinson disease, it compounds the sleep disturbances.

Other Movement Disorders

In one special group, disorders commonly evident during the day continue in sleep. This group includes generalized dystonia, tics, blepharospasm, and hemifacial spasm (see Chapter 18). Although partial arousals may precipitate these movements, most of them are not confined to a particular sleep stage.

Fatal Familial Insomnia

Like Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (see Chapter 7), FFI is a hereditary prion disease caused by a mutation of the prion protein gene (PRNP) that results in accumulation of abnormal prion protein (PrPSc). Individuals who are homozygous for the FFI mutation, compared to those who are heterozygous, tend to run a fulminant course characterized by severe sleep disturbances and profound ANS abnormalities. Heterozygous individuals, in contrast, run a longer course with predominantly motor deficits.

Epilepsy

In primary generalized epilepsy compared to partial epilepsy (see Chapter 10), sleep and particularly its NREM stages have a greater role in provoking seizures. About 45% of patients with primary generalized epilepsy have seizures predominantly during sleep. Primary generalized seizures most often develop within N1 and N2 sleep – usually during the first 2 hours of sleep. They also tend to occur at the other end of the sleep cycle – on awakening. REM sleep, in contrast, remains relatively seizure-free.

Headaches

In some migraine patients, headaches arise only during sleep (nocturnal migraines, see Chapter 9). REM sleep coincides with the onset of migraine and, even more closely, cluster headache. Migraines often begin during early-morning REM sleep as well as during the day. Naturally occurring or medication-induced sleep characteristically aborts them.

Insomnia

Pharmacologic Treatment

Hypnotics’ adverse reactions rather than lack of effectiveness limit their usefulness. Aside from several nonprescription medicines, hypnotics fall into three categories (Box 17-5). Nonprescription hypnotics, such as those containing antihistamines, are valuable; however, they are only effective for several days because patients build up tolerance, and these medicines commonly cause sleepiness and confusion. Moreover, they carry several potential worrisome side effects. For example, antihistamines – especially in children – can lead to delirium, confusion, nightmares, and dystonic reactions.

Tryptophan, another nonprescription medicine, had enjoyed popularity because it is the “active ingredient” in warm milk and some herbal sleep aids. Although it is a precursor of melatonin, tryptophan produces little hypnotic effect. Moreover, one batch of contaminated tryptophan pills caused the eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome (see Chapter 6). Also, when individuals under treatment with an SSRI take tryptophan, they risk developing the serotonin syndrome.

Abramowicz M. Gamma hydroxybutyrate (Xyrem) for narcolepsy. editor. Med Lett. 2002;44:103–105.

Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: Diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101–119.

American Sleep Disorders Association, Diagnostic Classification Steering Committee. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. Diagnostic and Coding Manual, ICSD-R. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005.

Arnulf I, Lin L, Gadoth N, et al. Kleine–Levin syndrome. A systematic study of 106 patients. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:482–493.

Barger LK, Cade BE, Ayas NT, et al. Extended work shifts and the risk of motor vehicle crashes among interns. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:125–134.

Broderick PJ, Benjamin AB. Caffeine and psychiatric symptoms: A review. J Okla State Med Assoc. 2004;97:538–542.

Broderick PJ, Benjamin AB, Dennis LW. Caffeine and psychiatric medication interactions: A review. J Okla State Med Assoc. 2005;98:380–384.

Cartwright R. Sleepwalking violence: A sleep disorder, legal dilemma, and a psychological challenge. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1149–1158.

Czeisler CA, Walsh JK, Roth T, et al. Modafinil for excessive sleepiness associated with shift-work disorder. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:476–486.

Dolder CR, Nelson MH. Hypnosedative-induced complex behaviors: Incidence mechanisms, and management. CNS Drugs. 2008;22:1021–1036.

Fantini ML, Ferini-Strambi L, Montplaisir J. Idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology. 2005;64:780–786.

Glazener CM, Evans JH, Peto RE. Alarm interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2, 2005. CD002911

Guilleminault C, Kirisoglu C, Bao G, et al. Adult chronic sleepwalking and its treatment based on polysomnography. Brain. 2005;128:1062–1069.

Howell MJ, Schenck CH, Crow SJ. A review of nighttime eating disorders. Sleep Rev. 2009;13:23–34.

Lack LC, Wright HR. Clinical management of delayed sleep phase disorders. Behav Sleep Med. 2007;5:57–76.

Lam SP, Fong SY, Yu MW, et al. Sleepwalking in psychiatric patients: Comparison of childhood and adult onset. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2009;43:426–430.

Lewy AJ. Melatonin and human chronobiology. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2007;72:623–636.

Mahowald MW, Schenck CH, Cramer-Bornemann MA. Sleep-related violence. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2005;5:153–158.

Neikrug AB, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep disorders in the older adult. Gerontology. 2010;56:181–189.

Owens JA, Belon K, Moss P. Impact of delaying school start time on adolescent sleep, mood, and behavior. Arch Pediatric. Adolesc Med. 2010;164:608–614.

Pilon M, Montplaisir J, Zadra A. Precipitating factors of somnambulism: Impact of sleep deprivation and forced arousals. Neurology. 2008;70:2284–2290.

Pressman MR. Factors that predispose, prime, and precipitate NREM parasomnias in adults: Clinical and forensic implications. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:5–30.

Rottach KG, Schaner BM, Kirch MH, et al. Restless legs syndrome as side effect of second generation antidepressants. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;43:70–75.

Sack RL. Jet lag. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:440–447.

Serra L, Montagna P, Mignot E, et al. Cataplexy features in childhood narcolepsy. Mov Disord. 2008;23:858–865.

Thorpy MJ, Plazzi G. The Parasomnias and Other Sleep-Related Movement Disorders. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

Winkelman JW, James L. Serotonergic antidepressants are associated with REM sleep without atonia. Sleep. 2004;27:317–321.

Zammit G, Wang-Weigand S, Rosenthal M, et al. Effect of ramelteon on middle-of-the-night balance in older adults with chronic insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:34–40.

Also, see National Center on Sleep Disorders website http://search.info.nih.gov

Chapter 17 Questions and Answers

1–15. As these statements apply to normal adult sleep, are they true or false?

1. Normal sleep progresses through the three nonrapid eye movement (NREM) stages before the first rapid eye movement (REM) sleep period.

2. Because REM sleep usually begins about 90–120 minutes after the onset of sleep, normal REM latency is 90–120 minutes.

3. The bulk of REM sleep occurs in the early night, whereas the bulk of NREM sleep occurs in the early morning.

4. The normal sequence of NREM–REM sleep recurs with a periodicity of about 90 minutes.

5. REM sleep is almost entirely devoid of physical and mental activity.

6. N3 NREM sleep provides great physical restfulness.

7. When an activity, such as falling asleep, shifts to later in the daily cycle, the change qualifies as a phase delay.

8. Aside from eye movement artifact, REM sleep electroencephalograms (EEGs) resemble ones during wakefulness.

9. EEG slow activity characterizes N3 NREM sleep.

10. The proportion of REM sleep in normal adults is unchanged from birth.

11. Social and occupational factors, rather than internal, physiologic mechanisms, override most individuals’ intrinsic sleep–wake schedule.

12. The proportion of time spent in slow-wave sleep increases in the elderly.

13. Some productive, vigorous, and well-rested people sleep as little as 5 hours nightly.

14. When an activity, such as falling asleep, shifts to earlier in the daily cycle, the change qualifies as a phase advance.

15. After they pass through adolescence, men no longer have penile erections during REM sleep.

16. In the night following sleep deprivation, which of the following will probably not occur?

17–24. Which of the following (17–24) are characteristic of factors a–d?

25–37. Which of the following phenomena (25–37) typically occur during phases a–d?

25-b; 26-a; 27-b; 28-b; 29-b; 30-a; 31-a; 32-b; 33-b; 34-a; 35-b; 36-d; 37-d.

40. Which of the following statements is untrue concerning sleep disturbances following the Oklahoma City bombing and previous, similar events?

41. A 34-year-old woman, over a year, develops burning in her feet that is so severe at night that it forces her to rub them incessantly and prevents her from sleeping. Then she still has to pace about for 1–2 hours. She has no ongoing medical illnesses and takes no medications. Aside from absent ankle reflexes, her neurologic examination is normal. Even with the numerous causes of this condition, which of the following laboratory tests is inappropriate?

43–47. Is each statement true or false?

43. Narcolepsy typically begins in middle age when normal afternoon fatigue becomes prominent.

44. Sleep apnea is a disorder only of adults.

45. Sleep apnea is associated with morning headaches and cardiovascular disorders.

46. Sleep apnea may lead to cognitive impairments and poor school performance.

47. Hypnopompic refers to phenomena that occur on awakening, and hypnagogic refers to phenomena that occur on falling asleep.

43. False. About 90% of cases develop between adolescence and age 25 years.

44. False. Children and teenagers, especially ones with nasopharyngeal abnormalities, have sleep apnea, the primary breathing-related disorder of sleep.

45. True. Sleep apnea is also associated with obesity, but the relationship is variable. About 30% of sleep apnea patients are not obese.

56. The parents of a 7-year-old boy bring him to a child psychiatrist because he has developed inattention and hyperactivity in school, especially in the early afternoon. Among their many observations, they note that he has begun to snore when he sleeps. The psychiatrist refers the patient to a pediatrician who finds enlarged tonsils and adenoids and diagnoses obstructive sleep apnea. A PSG confirms the diagnosis. What will be the probable outcome of a tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy?

57. A recently retired salesman, who appears in good physical and psychological health, complains of inability to fall asleep until 1:00 AM. Moreover, he also says that when he awakes, he has failed to obtain a restful night of sleep. Of the following, which advice should the physician offer him?

c. Practice good sleep hygiene before embarking on expensive testing or taking a hypnotic.

64. A college student accused his roommate of sexually attacking him on several occasions while he was asleep between 2 AM and 3 AM. He said that each time his roommate must have crossed their room, climbed into his bed, and began to fondle him. Although the accused student conceded that he awoke in or near his roommate’s bed, he denied any sexual advances and could not recall any details. He admitted that he had been sleep-deprived and consumed excess alcohol before the event. After physicians conducted a full psychiatric evaluation, which did not reveal homosexual tendencies, alcoholism, or paroxysmal EEG activity, they obtained a PSG study that revealed masturbation during NREM sleep. Which is the most likely diagnosis?

67. During the summer after his freshman year in college, Robert slept incessantly for 10 days. He would only awaken to use the toilet and eat large amounts of food – “like a hibernating bear,” according to his mother. His father, who called Robert a “zombie” when not in bed, found him masturbating several times. When his parents questioned him, Robert was reticent, unengaged, disoriented, and unable to recall recent events. During the previous summer, he had a similar period, but it lasted only 6 days. In addition, his parents thought that another occurred while he was away at college. Between these episodes, he was affable, bright, and hardworking. Neurologic and medical examinations, routine blood tests, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), lumbar puncture, EEG, and toxicology studies all showed no significant abnormalities during both episodes. Which disorder most likely has affected Robert?

73. A 25-year-old woman with anxiety disorder reports frequent episodes of various frightening thoughts that jar her awake from sleep. Once awake, she can recall her fears and is oriented and coherent. She then remains awake for almost an hour before returning to sleep. PSG shows that the episodes arise from NREM sleep and the EEG electrodes do not show paroxysmal discharges. Which is the most likely diagnosis?

77. An 18-year-old college freshman, who works parttime as a waitress, described having EDS. For the last 2 years she has had irresistible urges to sleep about twice daily, a tendency to become weak when laughing, and occasionally has total paralysis when attempting to wake for morning classes. Which one of the following is the next best step?

79. A 32-year-old psychiatry resident in the third trimester of her first pregnancy reports the development of unusual feelings to her training analyst. Beginning 2 days before, whenever she was “on the couch,” she wants to move her feet and walk around – as if to avoid further insights. Although characteristically reticent, the analyst remarked that it was more than a sensation because he leaned over and saw her feet moving. The analysand had no other symptoms and was taking no medications. Which is the most likely pregnancy-related disorder?

80. A 50-year-old man is brought for psychiatric consultation by his wife because he has become “distant, inattentive, and confused” during the previous several months. Two months before those symptoms developed, he began to have progressively severe insomnia, which hypnotics, antidepressants, and other psychotropic medicines did not alleviate. The patient’s older sister recently died after 18 months of a similar illness. The psychiatrist found that the patient had personality changes, cognitive deficits, and subtle myoclonus. An internist found that he had tachycardia and labile hypertension. Of the following, which is the most likely illness?

84. After having worked the previous 36 hours, an intern fell asleep at 2:00 AM. Her resident called her an hour later to ask her about a patient, but she did not know that she was at work and could not speak coherently. Her resident recognized the situation, terminated the conversation, and advised her to return to sleep. She could not remember the call in the morning. Which is the best term for the episode?

85. A 17-year-old student has spent the summer in a band. He went to sleep every night at 4:00 AM. Anticipating the start of school on September 1, he requests an “upper” to help him remain awake during the transition. What would be the best method to change to a sleep schedule of 11:00 PM to 6:30 AM?

88. A 35-year-old woman sought psychiatric consultation for mild depression, insomnia, and obesity. When discussing her obesity, which seems refractory to her stringent diet, she mentions that she cannot recall eating at night; however, she states that in the morning she occasionally finds open tuna cans and once an open cat food can on the kitchen floor. Although her obesity is undoubtedly multifactorial, which is the most likely explanation of the debris on the kitchen floor?

99. A 40-year-old secretary reports inability to fall asleep, frequent awakenings, and arising hours before necessary. She has EDS that she attributes to her insomnia. Her PSG shows prolonged sleep latency, frequent arousals interrupting sleep, reduced slow-wave and REM sleep, and advanced awakening. Which is the most likely diagnosis?

101. A 45-year-old school teacher reports having insomnia when attempting to fall asleep at 11 PM. She remains awake reading, using her computer, and doing household tasks. Once in bed between 1 and 2 AM she immediately falls asleep. She sleeps without interruption until the alarm clock awakens her at 6:30 AM. Then she has trouble awakening and during the school day has constant EDS. On weekends and holidays, she goes to bed and immediately falls asleep between 1 and 2 AM. She then sleeps until about 10 AM. On those days she awakes refreshed and has no EDS. On all days, she has only a single cup of coffee in the morning, and does not use other caffeine-containing beverage or food. She takes no alcohol or medications that would affect her sleep. She has no symptoms of a mood disorder or other psychiatric disturbance. Which would be the best treatment?

103. A 23-year-old aspiring actor requested evaluation for a sensation of falling coupled with a sudden contraction in his leg and back muscles, as if to prevent the fall, upon falling asleep. This sequence occurs once or twice a month after beginning to fall asleep after a particularly exhausting day. It not only frightens him but then it prohibits him from sleeping for another 30 minutes. Which strategy should the physician recommend?