315 |

Interstitial Lung Diseases |

Patients with interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) come to medical attention mainly because of the onset of progressive exertional dyspnea or a persistent nonproductive cough. Hemoptysis, wheezing, and chest pain may be present. Often, the identification of interstitial opacities on chest x-ray focuses the diagnostic approach on one of the ILDs.

ILDs represent a large number of conditions that involve the parenchyma of the lung—the alveoli, the alveolar epithelium, the capillary endothelium, and the spaces between those structures—as well as the perivascular and lymphatic tissues. The disorders in this heterogeneous group are classified together because of similar clinical, roentgenographic, physiologic, or pathologic manifestations. These disorders often are associated with considerable rates of morbidity and mortality, and there is little consensus regarding the best management of most of them.

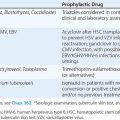

ILDs have been difficult to classify because >200 known individual diseases are characterized by diffuse parenchymal lung involvement, either as the primary condition or as a significant part of a multiorgan process, as may occur in the connective tissue diseases (CTDs). One useful approach to classification is to separate the ILDs into two groups based on the major underlying histopathology: (1) those associated with predominant inflammation and fibrosis and (2) those with a predominantly granulomatous reaction in interstitial or vascular areas (Table 315-1). Each of these groups can be subdivided further according to whether the cause is known or unknown. For each ILD there may be an acute phase, and there is usually a chronic one as well. Rarely, some are recurrent, with intervals of subclinical disease.

|

MAJOR CATEGORIES OF ALVEOLAR AND INTERSTITIAL INFLAMMATORY LUNG DISEASE |

Sarcoidosis (Chap. 390), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), and pulmonary fibrosis associated with CTDs (Chaps. 378, 382, 388, and 427) are the most common ILDs of unknown etiology. Among the ILDs of known cause, the largest group includes occupational and environmental exposures, especially the inhalation of inorganic dusts, organic dusts, and various fumes or gases (Chap. 311). A multidisciplinary approach—requiring close communication between clinician, radiologist, and when appropriate, pathologist—is often required to make the diagnosis. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scanning improves the diagnostic accuracy and may eliminate the need for tissue examination in many cases, especially in IPF. For other forms, tissue examination, usually obtained by thoracoscopic lung biopsy, is critical to confirmation of the diagnosis.

PATHOGENESIS

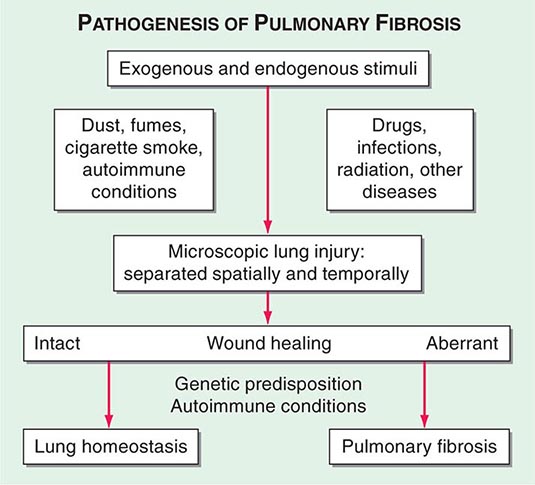

The ILDs are nonmalignant disorders and are not caused by identified infectious agents. The precise pathway(s) leading from injury to fibrosis is not known. Although there are multiple initiating agent(s) of injury, the immunopathogenic responses of lung tissue are limited, and the mechanisms of repair have common features (Fig. 315-1).

FIGURE 315-1 Proposed mechanism for the pathogenesis of pulmonary fibrosis. The lung is naturally exposed to repetitive injury from a variety of exogenous and endogenous stimuli. Several local and systemic factors (e.g., fibroblasts, circulating fibrocytes, chemokines, growth factors, and clotting factors) contribute to tissue healing and functional recovery. Dysregulation of this intricate network through genetic predisposition, autoimmune conditions, or super-imposed diseases can lead to aberrant wound healing, with the result of pulmonary fibrosis. Alternatively, excessive injury to the lung may overwhelm even intact reparative mechanisms and lead to pulmonary fibrosis. (From S Garantziotis et al: J Clin Invest 114:319, 2004.)

As mentioned above, the two major histopathologic patterns are a granulomatous pattern and a pattern in which inflammation and fibrosis predominate.

Granulomatous Lung Disease This process is characterized by an accumulation of T lymphocytes, macrophages, and epithelioid cells organized into discrete structures (granulomas) in the lung parenchyma. The granulomatous lesions can progress to fibrosis. Many patients with granulomatous lung disease remain free of severe impairment of lung function or, when symptomatic, improve after treatment. The main differential diagnosis is between sarcoidosis (Chap. 390) and hypersensitivity pneumonitis (Chap. 310).

Inflammation and Fibrosis The initial insult is an injury to the epithelial surface that causes inflammation in the air spaces and alveolar walls. If the disease becomes chronic, inflammation spreads to adjacent portions of the interstitium and vasculature and eventually causes interstitial fibrosis. Important histopathologic patterns found in the ILDs include usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, respiratory bronchiolitis/desquamative interstitial pneumonia, organizing pneumonia, diffuse alveolar damage (acute or organizing), and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia. The development of irreversible scarring (fibrosis) of alveolar walls, airways, or vasculature is the most feared outcome in all of these conditions because it is often progressive and leads to significant derangement of ventilatory function and gas exchange.

HISTORY

Duration of Illness Acute presentation (days to weeks), although unusual, occurs with allergy (drugs, fungi, helminths), acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP), eosinophilic pneumonia, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. These conditions may be confused with atypical pneumonias because of diffuse alveolar opacities on chest x-ray. Subacute presentation (weeks to months) may occur in all ILDs but is seen especially in sarcoidosis, drug-induced ILDs, the alveolar hemorrhage syndromes, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), and the acute immunologic pneumonia that complicates systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or polymyositis. In most ILDs, the symptoms and signs form a chronic presentation (months to years). Examples include IPF, sarcoidosis, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis (PLCH), pneumoconioses, and CTDs. Episodic presentations are unusual and include eosinophilic pneumonia, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, COP, vasculitides, pulmonary hemorrhage, and Churg-Strauss syndrome.

Age Most patients with sarcoidosis, ILD associated with CTD, lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), PLCH, and inherited forms of ILD (familial IPF, Gaucher disease, Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome) present between the ages of 20 and 40 years. Most patients with IPF are older than 60 years.

Gender LAM and pulmonary involvement in tuberous sclerosis occur exclusively in premenopausal women. In addition, ILD in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome and in the CTDs is more common in women; an exception is ILD in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), which is more common in men. IPF is more common in men. Because of occupational exposures, pneumoconioses also occur more frequently in men.

Family History Familial lung fibrosis has been associated with mutations in the surfactant protein C gene, the surfactant protein A2 gene, telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT), telomerase RNA component (TERC), and the promoter of a mucin gene (MUC5B). Familial lung fibrosis is characterized by several patterns of interstitial pneumonia, including nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, desquamative interstitial pneumonia, and UIP. Older age, male sex, and a history of cigarette smoking have been identified as risk factors for familial lung fibrosis. Family associations (with an autosomal dominant pattern) have been identified in tuberous sclerosis and neurofibromatosis. Familial clustering has been identified increasingly in sarcoidosis. The genes responsible for several rare ILDs have been identified, i.e., alveolar microlithiasis, Gaucher disease, Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome, and Niemann-Pick disease, along with the genes for surfactant homeostasis in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis and for control of cell growth and differentiation in LAM.

Smoking History Two-thirds to 75% of patients with IPF and familial lung fibrosis have a history of smoking. Patients with PLCH, respiratory bronchiolitis/desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP), Goodpasture syndrome, respiratory bronchiolitis, and pulmonary alveolar proteinosis are usually current or former smokers.

Occupational and Environmental History A strict chronologic listing of the patient’s lifelong employment must be sought, including specific duties and known exposures. In hypersensitivity pneumonitis (see Fig. 310-1), respiratory symptoms, fever, chills, and an abnormal chest roentgenogram are often temporally related to a hobby (pigeon breeder’s disease) or to the workplace (farmer’s lung) (Chap. 310). Symptoms may diminish or disappear after the patient leaves the site of exposure for several days; similarly, symptoms may reappear when the patient returns to the exposure site.

Other Important Past History Parasitic infections may cause pulmonary eosinophilia, and therefore a travel history should be taken in patients with known or suspected ILD. History of risk factors for HIV infection should be elicited because several processes may occur at the time of initial presentation or during the clinical course, e.g., HIV infection, organizing pneumonia, AIP, lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis, and diffuse alveolar hemorrhage.

Respiratory Symptoms and Signs Dyspnea is a common and prominent complaint in patients with ILD, especially the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, COP, sarcoidosis, eosinophilic pneumonias, and PLCH. Some patients, especially those with sarcoidosis, silicosis, PLCH, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, lipoid pneumonia, or lymphangitis carcinomatosis, may have extensive parenchymal lung disease on chest imaging studies without significant dyspnea, especially early in the course of the illness. Wheezing is an uncommon manifestation of ILD but has been described in patients with chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, Churg-Strauss syndrome, respiratory bronchiolitis, and sarcoidosis. Clinically significant chest pain is uncommon in most ILDs. However, substernal discomfort is common in sarcoidosis. Sudden worsening of dyspnea, especially if associated with acute chest pain, may indicate a spontaneous pneumothorax, which occurs in PLCH, tuberous sclerosis, LAM, and neurofibromatosis. Frank hemoptysis and blood-streaked sputum are rarely presenting manifestations of ILD but can be seen in the diffuse alveolar hemorrhage (DAH) syndromes, LAM, tuberous sclerosis, and the granulomatous vasculitides. Fatigue and weight loss are common in all ILDs.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The findings are usually not specific. Most commonly, physical examination reveals tachypnea and bibasilar end-inspiratory dry crackles, which are common in most forms of ILD associated with inflammation but are less likely to be heard in the granulomatous lung diseases. Crackles may be present in the absence of radiographic abnormalities on the chest radiograph. Scattered late inspiratory high-pitched rhonchi—so-called inspiratory squeaks—are heard in patients with bronchiolitis. The cardiac examination is usually normal except in the middle or late stages of the disease, when findings of pulmonary hypertension and cor pulmonale may become evident (Chap. 304). Cyanosis and clubbing of the digits occur in some patients with advanced disease.

LABORATORY

Antinuclear antibodies and anti-immunoglobulin antibodies (rheumatoid factors) are identified in some patients, even in the absence of a defined CTD. A raised lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level is a nonspecific finding common to ILDs. Elevation of the serum level of angiotensin-converting enzyme is common in ILDs, especially sarcoidosis. Serum precipitins confirm exposure when hypersensitivity pneumonitis is suspected, although they are not diagnostic of the process. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic or anti-basement membrane antibodies are useful if vasculitis is suspected. The electrocardiogram is usually normal unless pulmonary hypertension is present; then it demonstrates right-axis deviation, right ventricular hypertrophy, or right atrial enlargement or hypertrophy. Echocardiography also reveals right ventricular dilation and/or hypertrophy in the presence of pulmonary hypertension.

CHEST IMAGING STUDIES

Chest X-Ray ILD may be first suspected on the basis of an abnormal chest radiograph, which most commonly reveals a bibasilar reticular pattern. A nodular or mixed pattern of alveolar filling and increased reticular markings also may be present. Subgroups of ILDs exhibit nodular opacities with a predilection for the upper lung zones (sarcoidosis, PLCH, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, silicosis, berylliosis, RA [necrobiotic nodular form], ankylosing spondylitis). The chest x-ray correlates poorly with the clinical or histopathologic stage of the disease. The radiographic finding of honeycombing correlates with pathologic findings of small cystic spaces and progressive fibrosis; when present, it portends a poor prognosis. In most cases, the chest radiograph is nonspecific and usually does not allow a specific diagnosis.

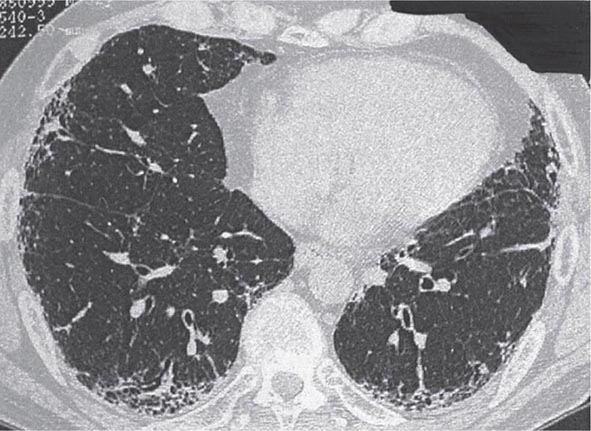

Computed Tomography HRCT is superior to the plain chest x-ray for early detection and confirmation of suspected ILD (Fig. 315-2). In addition, HRCT allows better assessment of the extent and distribution of disease, and it is especially useful in the investigation of patients with a normal chest radiograph. Coexisting disease is often best recognized on HRCT scanning, e.g., mediastinal adenopathy, carcinoma, or emphysema. In the appropriate clinical setting, HRCT may be sufficiently characteristic to preclude the need for lung biopsy in IPF, sarcoidosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, asbestosis, lymphangitic carcinoma, and PLCH. When a lung biopsy is required, HRCT scanning is useful for determining the most appropriate area from which biopsy samples should be taken.

FIGURE 315-2 Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. High-resolution computed tomography image shows bibasal, peripheral predominant reticular abnormality with traction bronchiectasis and honeycombing. The lung biopsy showed the typical features of usual interstitial pneumonia.

PULMONARY FUNCTION TESTING

Spirometry and Lung Volumes Measurement of lung function is important in assessing the extent of pulmonary involvement in patients with ILD. Most forms of ILD produce a restrictive defect with reduced total lung capacity (TLC), functional residual capacity, and residual volume (Chap. 306e). Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) are reduced, but these changes are related to the decreased TLC. The FEV1/FVC ratio is usually normal or increased. Lung volumes decrease as lung stiffness worsens with disease progression. A few disorders produce interstitial opacities on chest x-ray and obstructive airflow limitation on lung function testing (uncommon in sarcoidosis and hypersensitivity pneumonitis but common in tuberous sclerosis and LAM). Pulmonary function studies have been proved to have prognostic value in patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, particularly IPF and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP).

Diffusing Capacity A reduction in the diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) is a common but nonspecific finding in most ILDs. This decrease is due in part to effacement of the alveolar capillary units but, more important, to mismatching of ventilation and perfusion (![]() /

/![]() ). Lung regions with reduced compliance due to either fibrosis or cellular infiltration may be poorly ventilated but may still maintain adequate blood flow, and the ventilation-perfusion mismatch in these regions acts like true venous admixture. The severity of the reduction in DLCO does not correlate with disease stage.

). Lung regions with reduced compliance due to either fibrosis or cellular infiltration may be poorly ventilated but may still maintain adequate blood flow, and the ventilation-perfusion mismatch in these regions acts like true venous admixture. The severity of the reduction in DLCO does not correlate with disease stage.

Arterial Blood Gas The resting arterial blood gas may be normal or reveal hypoxemia (secondary to a mismatching of ventilation to perfusion) and respiratory alkalosis. A normal arterial O2 tension (or saturation by oximetry) at rest does not rule out significant hypoxemia during exercise or sleep. Carbon dioxide (CO2) retention is rare and is usually a manifestation of end-stage disease.

CARDIOPULMONARY EXERCISE TESTING

Because hypoxemia at rest is not always present and because severe exercise-induced hypoxemia may go undetected, it is useful to perform exercise testing with measurement of arterial blood gases to detect abnormalities of gas exchange. Arterial oxygen desaturation, a failure to decrease dead space appropriately with exercise (i.e., a high VD/VT [dead space/tidal volume] ratio [Chap. 306e]), and an excessive increase in respiratory rate with a lower than expected recruitment of tidal volume provide useful information about physiologic abnormalities and extent of disease. Serial assessment of resting and exercise gas exchange is an excellent method for following disease activity and responsiveness to treatment, especially in patients with IPF. Increasingly, the 6-min walk test is used to obtain a global evaluation of submaximal exercise capacity in patients with ILD. The walk distance and level of oxygen desaturation tend to correlate with the patient’s baseline lung function and mirror the patient’s clinical course.

FIBEROPTIC BRONCHOSCOPY AND BRONCHOALVEOLAR LAVAGE (BAL)

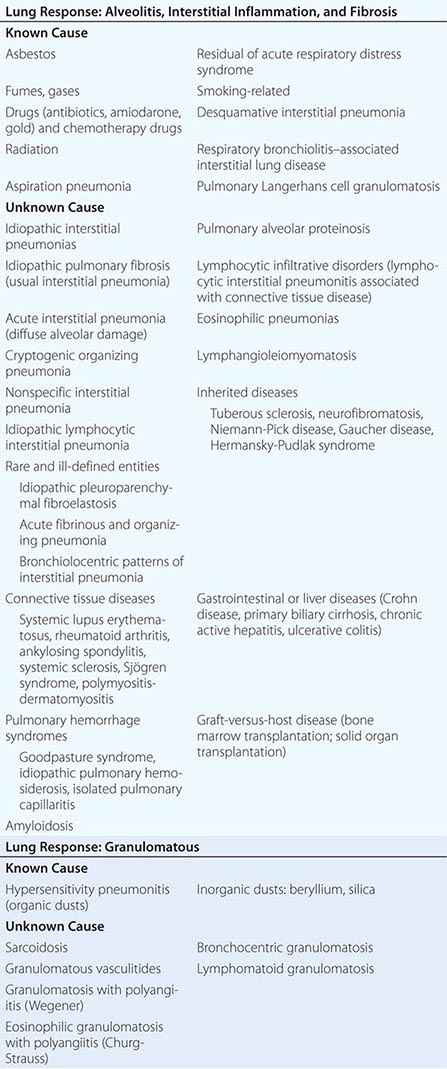

In selected diseases (e.g., sarcoidosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, DAH syndrome, cancer, pulmonary alveolar proteinosis), cellular analysis of BAL fluid may be useful in narrowing the differential diagnostic possibilities among various types of ILD (Table 315-2). The role of BAL in defining the stage of disease and assessment of disease progression or response to therapy remains poorly understood, and the usefulness of BAL in the clinical assessment and management remains to be established.

|

DIAGNOSTIC VALUE OF BRONCHOALVEOLAR LAVAGE IN INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASE |

TISSUE AND CELLULAR EXAMINATION

Lung biopsy is the most effective method for confirming the diagnosis and assessing disease activity. The findings may identify a more treatable process than originally suspected, particularly chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, COP, respiratory bronchiolitis–associated ILD, or sarcoidosis. Biopsy should be obtained before the initiation of treatment. A definitive diagnosis avoids confusion and anxiety later in the clinical course if the patient does not respond to therapy or experiences serious side effects from it.

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy with multiple transbronchial lung biopsies (four to eight biopsy samples) is often the initial procedure of choice, especially when sarcoidosis, lymphangitic carcinomatosis, eosinophilic pneumonia, Goodpasture syndrome, or infection is suspected. If a specific diagnosis is not made by transbronchial biopsy, surgical lung biopsy by video-assisted thoracic surgery or open thoracotomy is indicated. Adequate-sized biopsies from multiple sites, usually from two lobes, should be obtained. Relative contraindications to lung biopsy include serious cardiovascular disease, honeycombing and other roentgenographic evidence of diffuse end-stage disease, severe pulmonary dysfunction, and other major operative risks, especially in the elderly.

INDIVIDUAL FORMS OF INTERSTITIAL LUNG DISEASE

IDIOPATHIC PULMONARY FIBROSIS

IPF is the most common form of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Separating IPF from other forms of lung fibrosis is an important step in the evaluation of all patients presenting with ILD. IPF has a distinctly poor response to therapy and a bad prognosis.

Clinical Manifestations Exertional dyspnea, a nonproductive cough, and inspiratory crackles with or without digital clubbing may be present on physical examination. HRCT lung scans typically show patchy, predominantly basilar, subpleural reticular opacities, often associated with traction bronchiectasis and honeycombing (Fig. 315-2). A definite UIP pattern on HRCT is highly accurate for the presence of a UIP pattern on surgical lung biopsy. Atypical findings that should suggest an alternative diagnosis include extensive ground-glass abnormality, nodular opacities, upper or midzone predominance, and prominent hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Pulmonary function tests often reveal a restrictive pattern, a reduced DLCO, and arterial hypoxemia that is exaggerated or elicited by exercise.

Histologic Findings Confirmation of the presence of the UIP pattern on histologic examination is essential to confirm this diagnosis. Transbronchial biopsies are not helpful in making the diagnosis of UIP, and surgical biopsy usually is required. The histologic hallmark and chief diagnostic criterion of UIP is a heterogeneous appearance at low magnification with alternating areas of normal lung, interstitial inflammation, foci of proliferating fibroblasts, dense collagen fibrosis, and honeycomb changes. These histologic changes affect the peripheral, subpleural parenchyma most severely. The interstitial inflammation is usually patchy and consists of a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in the alveolar septa, associated with hyperplasia of type 2 pneumocytes. The fibrotic zones are composed mainly of dense collagen, although scattered foci of proliferating fibroblasts are a consistent finding. The extent of fibroblastic proliferation is predictive of disease progression. Areas of honeycomb change are composed of cystic fibrotic air spaces that frequently are lined by bronchiolar epithelium and filled with mucin. Smooth-muscle hyperplasia is commonly seen in areas of fibrosis and honeycomb change. A fibrotic pattern with some features similar to UIP may be found in the chronic stage of several specific disorders, such as pneumoconioses (e.g., asbestosis), radiation injury, certain drug-induced lung diseases (e.g., nitrofurantoin), chronic aspiration, sarcoidosis, chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis, organized chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, and PLCH. Commonly, other histopathologic features are present in these situations, thus allowing separation of these lesions from the UIP-like pattern. Consequently, the term usual interstitial pneumonia is used for patients in whom the lesion is idiopathic and not associated with another condition.

NONSPECIFIC INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIA

This condition defines a subgroup of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias that can be distinguished clinically and pathologically from UIP, DIP, AIP, and COP. Importantly, many cases with this histopathologic pattern occur in the context of an underlying disorder, such as a CTD, drug-induced ILD, or chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Clinical Manifestations Patients with idiopathic NSIP have clinical, serologic, radiographic, and pathologic characteristics highly suggestive of autoimmune disease and meet the criteria for undifferentiated CTD. Idiopathic NSIP is a subacute restrictive process with a presentation similar to that of IPF but usually at a younger age, most commonly in women who have never smoked. It is often associated with a febrile illness. HRCT shows bilateral, subpleural ground-glass opacities, often associated with lower lobe volume loss (Fig. 315-3). Patchy areas of airspace consolidation and reticular abnormalities may be present, but honeycombing is unusual.

FIGURE 315-3 Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. High-resolution computed tomography through the lower lung shows volume loss with extensive ground-glass abnormality, reticular abnormality, and traction bronchiectasis. There is sparing on the lung immediately adjacent to the pleura. Histology showed a combination of inflammation and mild fibrosis.

Histologic Findings The key histopathologic feature of NSIP is the uniformity of interstitial involvement across the biopsy section, and this may be predominantly cellular or fibrosing. There is less temporal and spatial heterogeneity than in UIP, and little or no honeycombing is found. The cellular variant is rare.

Treatment The majority of patients with NSIP have a good prognosis (5-year mortality rate estimated at <15%), with most showing improvement after treatment with glucocorticoids, often used in combination with azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil.

ACUTE INTERSTITIAL PNEUMONIA (HAMMAN-RICH SYNDROME)

Clinical Manifestations AIP is a rare, fulminant form of lung injury characterized histologically by diffuse alveolar damage on lung biopsy. Most patients are older than 40 years. AIP is similar in presentation to the acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (Chap. 322) and probably corresponds to the subset of cases of idiopathic ARDS. The onset is usually abrupt in a previously healthy individual. A prodromal illness, usually lasting 7–14 days before presentation, is common. Fever, cough, and dyspnea are common manifestations at presentation. Diffuse, bilateral, air-space opacification is present on the chest radiograph. HRCT scans show bilateral, patchy, symmetric areas of ground-glass attenuation. Bilateral areas of air-space consolidation also may be present. A predominantly subpleural distribution may be seen.

Histologic Findings The diagnosis of AIP requires the presence of a clinical syndrome of idiopathic ARDS and pathologic confirmation of organizing diffuse alveolar damage. Therefore, lung biopsy is required to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment Most patients have moderate to severe hypoxemia and develop respiratory failure. Mechanical ventilation is often required. The mortality rate is high (>60%), with most patients dying within 6 months of presentation. Recurrences have been reported. However, those who recover often have substantial improvement in lung function. The main treatment is supportive. It is not clear that glucocorticoid therapy is effective.

CRYPTOGENIC ORGANIZING PNEUMONIA

Clinical Manifestations COP is a clinicopathologic syndrome of unknown etiology. The onset is usually in the fifth and sixth decades. The presentation may be of a flulike illness with cough, fever, malaise, fatigue, and weight loss. Inspiratory crackles are frequently present on examination. Pulmonary function is usually impaired, with a restrictive defect and arterial hypoxemia being most common. The roentgenographic manifestations are distinctive, revealing bilateral, patchy, or diffuse alveolar opacities in the presence of normal lung volume. Recurrent and migratory pulmonary opacities are common. HRCT shows areas of air-space consolidation, ground-glass opacities, small nodular opacities, and bronchial wall thickening and dilation. These changes occur more frequently in the periphery of the lung and in the lower lung zone.

Histologic Findings Lung biopsy shows granulation tissue within small airways, alveolar ducts, and airspaces, with chronic inflammation in the surrounding alveoli. Foci of organizing pneumonia are a nonspecific reaction to lung injury found adjacent to other pathologic processes or as a component of other primary pulmonary disorders (e.g., cryptococcosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis [Wegener], lymphoma, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and eosinophilic pneumonia). Consequently, the clinician must carefully reevaluate any patient found to have this histopathologic lesion to rule out these possibilities.

Treatment Glucocorticoid therapy induces clinical recovery in two-thirds of patients. A few patients have rapidly progressive courses with fatal outcomes despite glucocorticoids.

ILD ASSOCIATED WITH CIGARETTE SMOKING

Desquamative Interstitial Pneumonia • CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS DIP is a rare but distinct clinical and pathologic entity found almost exclusively in cigarette smokers. The histologic hallmark is the extensive accumulation of macrophages in intraalveolar spaces with minimal interstitial fibrosis. The peak incidence is in the fourth and fifth decades. Most patients present with dyspnea and cough. Lung function testing shows a restrictive pattern with reduced DLCO and arterial hypoxemia. The chest x-ray and HRCT scans usually show diffuse hazy opacities.

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS A diffuse and uniform accumulation of macrophages in the alveolar spaces is the hallmark of DIP. The macrophages contain golden, brown, or black pigment of tobacco smoke. There may be mild thickening of the alveolar walls by fibrosis and scanty inflammatory cell infiltration.

TREATMENT Clinical recognition of DIP is important because the process is associated with a better prognosis (10-year survival rate is ~70%) in response to smoking cessation. There are no clear data showing that systemic glucocorticoids are effective in DIP.

Respiratory Bronchiolitis–Associated ILD • CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS Respiratory bronchiolitis–associated ILD (RB-ILD) is considered to be a subset of DIP and is characterized by the accumulation of macrophages in peribronchial alveoli. The clinical presentation is similar to that of DIP. Crackles are often heard on chest examination and occur throughout inspiration; sometimes they continue into expiration. The process is best seen on HRCT lung scanning, which shows bronchial wall thickening, centrilobular nodules, ground-glass opacity, and emphysema with air trapping. There is a spectrum of CT features in asymptomatic smokers (and elderly asymptomatic individuals) that may not necessarily represent clinically relevant disease.

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS The histologic findings in RB-ILD include alveolar macrophage accumulation in respiratory bronchioles, with a variable chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate in bronchiolar and surrounding alveolar walls and occasional peribronchial alveolar septal fibrosis. The pulmonary parenchyma may show presence of smoking-related emphysema.

TREATMENT RB-ILD appears to resolve in most patients after smoking cessation alone.

Pulmonary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis • CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS This is a rare, smoking-related, diffuse lung disease that primarily affects men between the ages of 20 and 40 years. The clinical presentation varies from an asymptomatic state to a rapidly progressive condition. The most common clinical manifestations at presentation are cough, dyspnea, chest pain, weight loss, and fever. Pneumothorax occurs in ~25% of patients. Hemoptysis and diabetes insipidus are rare manifestations. The radiographic features vary with the stage of the disease. The combination of ill-defined or stellate nodules (2–10 mm in diameter), reticular or nodular opacities, bizarre-shaped upper zone cysts, preservation of lung volume, and sparing of the costophrenic angles are characteristics of PLCH. HRCT that reveals a combination of nodules and thin-walled cysts is virtually diagnostic of PLCH. The most common pulmonary function abnormality is a markedly reduced DLCO, although varying degrees of restrictive disease, airflow limitation, and diminished exercise capacity may occur.

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS The characteristic histopathologic finding in PLCH is the presence of nodular sclerosing lesions that contain Langerhans cells accompanied by mixed cellular infiltrates. The nodular lesions are poorly defined and are distributed in a bronchiolocentric fashion with intervening normal lung parenchyma. As the disease advances, fibrosis progresses to involve adjacent lung tissue, leading to pericicatricial air space enlargement, which accounts for the concomitant cystic changes.

TREATMENT Discontinuance of smoking is the key treatment, resulting in clinical improvement in one-third of patients. Most patients with PLCH experience persistent or progressive disease. Death due to respiratory failure occurs in ~10% of patients.

ILD ASSOCIATED WITH CONNECTIVE TISSUE DISORDERS

Clinical findings suggestive of a CTD (musculoskeletal pain, weakness, fatigue, fever, joint pain or swelling, photosensitivity, Raynaud’s phenomenon, pleuritis, dry eyes, dry mouth) should be sought in any patient with ILD. The CTDs may be difficult to rule out since the pulmonary manifestations occasionally precede the more typical systemic manifestations by months or years. The most common form of pulmonary involvement is the nonspecific interstitial pneumonia histopathologic pattern. However, determining the precise nature of lung involvement in most of the CTDs is difficult due to the high incidence of lung involvement caused by disease-associated complications of esophageal dysfunction (predisposing to aspiration and secondary infections), respiratory muscle weakness (atelectasis and secondary infections), complications of therapy (opportunistic infections), and associated malignancies. For the majority of CTDs, with the exception of progressive system sclerosis, recommended initial treatment for ILD includes oral glucocorticoids often in association with an immunosuppressive agent (usually oral or intravenous cyclophosphamide or oral azathioprine) or mycophenolate mofetil.

Progressive Systemic Sclerosis (PSS) • CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS (See also Chap. 382) Clinical evidence of ILD is present in about one-half of patients with PSS, and pathologic evidence in three-quarters. Pulmonary function tests show a restrictive pattern and impaired diffusing capacity, often before any clinical or radiographic evidence of lung disease appears. The HRCT features of lung disease in PSS range from predominant ground-glass attenuation to a predominant reticular pattern and are mostly similar to idiopathic NSIP.

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS NSIP is the histopathologic pattern in most patients (~75%); the UIP pattern is rare (<10%).

TREATMENT Therapy is similar to that in idiopathic NSIP. UIP in PSS has a better outcome than IPF. The most widely used initial treatment regimen is low-dose glucocorticoid therapy and an immunosuppressive agent, usually oral or pulse cyclophosphamide. There are no convincing data showing this regime to be efficacious, and there is concern that the risk of renal crisis rises substantially with corticosteroids. Pulmonary vascular disease alone or in association with pulmonary fibrosis, pleuritis, or recurrent aspiration pneumonitis is strikingly resistant to current modes of therapy.

Rheumatoid Arthritis • CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS (See also Chap. 380) ILD associated with RA is more common in men. Pulmonary manifestations of RA include pleurisy with or without effusion, ILD in up to 20% of cases, necrobiotic nodules (nonpneumoconiotic intrapulmonary rheumatoid nodules) with or without cavities, Caplan syndrome (rheumatoid pneumoconiosis), pulmonary hypertension secondary to rheumatoid pulmonary vasculitis, organized pneumonia, and upper airway obstruction due to cricoarytenoid arthritis.

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS There are two primary histopathologic patterns of ILD that are observed in patients with ILD associated with RA: NSIP pattern and UIP pattern.

TREATMENT Little data exist to support the management of ILD in RA. Initial treatment of rheumatoid ILD, if required, is typically with oral glucocorticoids, which should be tried for 1–3 months. The potential benefit of anti-tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) therapy has been clouded by concerns about the development of a rapid and occasionally fatal lung disease in patients with RA-associated ILD treated with anti-TNF-α therapy.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus • CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS (See also Chap. 378) Lung disease is a common complication in SLE. Pleuritis with or without effusion is the most common pulmonary manifestation. Other lung manifestations include the following: atelectasis, diaphragmatic dysfunction with loss of lung volumes, pulmonary vascular disease, pulmonary hemorrhage, uremic pulmonary edema, infectious pneumonia, and organized pneumonia. Acute lupus pneumonitis characterized by pulmonary capillaritis leading to alveolar hemorrhage is uncommon. Chronic, progressive ILD is uncommon (<10%). It is important to exclude pulmonary infection. Although pleuropulmonary involvement may not be evident clinically, pulmonary function testing, particularly DLCO, reveals abnormalities in many patients with SLE.

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS The most common pathologic patterns seen include NSIP, UIP, LIP, and, on occasion, organizing pneumonia and amyloidosis.

TREATMENT There have been no controlled trials of treatment for ILD in SLE. Treatment involves the use of a glucocorticoid, either alone or, more often, in combination with an additional immunomodulating agent.

Polymyositis and Dermatomyositis (PM/DM) • CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS (See also Chap. 388) ILD occurs in ~10% of patients with PM/DM. Diffuse reticular or nodular opacities with or without an alveolar component occur radiographically, with a predilection for the lung bases (NSIP pattern). ILD occurs more commonly in the subgroup of patients with an anti-Jo-1 antibody that is directed to histidyl tRNA synthetase. Weakness of respiratory muscles contributing to aspiration pneumonia may be present. A rapidly progressive illness characterized by diffuse alveolar damage may cause respiratory failure.

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS NSIP predominates over UIP, organizing pneumonia, or other patterns of interstitial pneumonia.

TREATMENT The optimal treatment is unknown. The most widely used initial treatment is oral glucocorticoids. Fulminant disease may require high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (1.0 g/d) for 3–5 days.

Sjögren Syndrome • CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS (See also Chap. 383) General dryness and lack of airway secretion cause the major problems of hoarseness, cough, and bronchitis.

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS Lung biopsy is frequently required to establish a precise pulmonary diagnosis. Fibrotic NSIP is most common. Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis, lymphoma, pseudolymphoma, bronchiolitis, and bronchiolitis obliterans are associated with this condition.

TREATMENT Glucocorticoids have been used in the management of ILD associated with Sjögren syndrome with some degree of clinical success.

DRUG-INDUCED ILD

Clinical Manifestations Many classes of drugs have the potential to induce diffuse ILD, which is manifest most commonly as exertional dyspnea and nonproductive cough. A detailed history of the medications taken by the patient is needed to identify drug-induced disease, including over-the-counter medications, oily nose drops, and petroleum products (mineral oil). In most cases, the pathogenesis is unknown, although a combination of direct toxic effects of the drug (or its metabolite) and indirect inflammatory and immunologic events are likely. The onset of the illness may be abrupt and fulminant, or it may be insidious, extending over weeks to months. The drug may have been taken for several years before a reaction develops (e.g., amiodarone), or the lung disease may occur weeks to years after the drug has been discontinued (e.g., carmustine). The extent and severity of disease are usually dose-related.

Histologic Findings The patterns of lung injury vary widely and depend on the agent.

Treatment Treatment consists of discontinuation of any possible offending drug and supportive care.

EOSINOPHILIC PNEUMONIA

(see Chap. 310)

PULMONARY ALVEOLAR PROTEINOSIS (PAP)

Clinical Manifestations Although not strictly an ILD, PAP resembles and is therefore considered with these conditions. It has been proposed that a defect in macrophage function, more specifically an impaired ability to process surfactant, may play a role in the pathogenesis of PAP. PAP is an autoimmune disease with a neutralizing antibody of immunoglobulin G isotype against granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). These findings suggest that neutralization of GM-CSF bioactivity by the antibody causes dysfunction of alveolar macrophages, which results in reduced surfactant clearance. There are three distinct classes of PAP: acquired (>90% of all cases), congenital, and secondary. Congenital PAP is transmitted in an autosomal recessive manner and is caused by homozygosity for a frameshift mutation (121ins2) in the SP-B gene, which leads to an unstable SP-B mRNA, reduced protein levels, and secondary disturbances of SP-C processing. Secondary PAP is rare among adults and is caused by lysinuric protein intolerance, acute silicosis and other inhalational syndromes, immunodeficiency disorders, and malignancies (almost exclusively of hematopoietic origin) and hematopoietic disorders.

The typical age of presentation is 30–50 years, and males predominate. The clinical presentation is usually insidious and is manifested by progressive exertional dyspnea, fatigue, weight loss, and low-grade fever. A nonproductive cough is common, but occasionally expectoration of “chunky” gelatinous material may occur. Polycythemia, hypergammaglobulinemia, and increased LDH levels are common. Markedly elevated serum levels of lung surfactant proteins A and D have been found in PAP. In the absence of any known secondary cause of PAP, an elevated serum anti-GM-CSF titer is highly sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of acquired PAP. BAL fluid levels of anti-GM-CSF antibodies correlate better with the severity of PAP than do serum titers. Radiographically, bilateral symmetric alveolar opacities located centrally in middle and lower lung zones result in a “bat-wing” distribution. HRCT shows a ground-glass opacification and thickened intralobular structures and interlobular septa.

Histologic Findings This diffuse disease is characterized by the accumulation of an amorphous, periodic acid–Schiff–positive lipoproteinaceous material in the distal air spaces. There is little or no lung inflammation, and the underlying lung architecture is preserved.

Treatment Whole-lung lavage(s) through a double-lumen endotracheal tube provides relief to many patients with dyspnea or progressive hypoxemia and also may provide long-term benefit.

PULMONARY LYMPHANGIOLEIOMYOMATOSIS

Clinical Manifestations Pulmonary LAM is a rare condition that afflicts premenopausal women and should be suspected in young women with “emphysema,” recurrent pneumothorax, or chylous pleural effusion. It is often misdiagnosed as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Whites are affected much more commonly than are members of other racial groups. The disease accelerates during pregnancy and abates after oophorectomy. Common complaints at presentation are dyspnea, cough, and chest pain. Hemoptysis may be life threatening. Spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in 50% of patients; it may be bilateral and necessitate pleurodesis. Meningioma and renal angiomyolipomas (hamartomas), characteristic findings in the genetic disorder tuberous sclerosis, are also common in patients with LAM. Chylothorax, chyloperitoneum (chylous ascites), chyluria, and chylopericardium are other complications. Pulmonary function testing usually reveals an obstructive or mixed obstructive-restrictive pattern, and gas exchange is often abnormal. HRCT shows thin-walled cysts surrounded by normal lung without zonal predominance.

Histologic Findings Pathologically, LAM is characterized by the proliferation of atypical pulmonary interstitial smooth muscle and cyst formation. The immature-appearing smooth-muscle cells react with monoclonal antibody HMB45, which recognizes a 100-kDa glycoprotein (gp100) originally found in human melanoma cells.

Treatment Progression is common, with a median survival of 8–10 years from diagnosis. No therapy is of proven benefit in LAM. Sirolimus, an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), appears to be an active agent for LAM. After 12 months, it stabilized lung function (FVC, FEV1, and functional residual capacity) and was associated with a reduction in symptoms and improvement in quality of life. Adverse effects (e.g., mucositis, diarrhea, nausea, hypercholesterolemia, acneiform rash, peripheral edema) were more common in the sirolimus group, but serious adverse effects were not increased. Subjects were followed off sirolimus for an additional 12 months, during which time pulmonary function declined at the same rate as in the placebo group. Progesterone and luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone analogues have been used. Oophorectomy is no longer recommended, and estrogen-containing drugs should be discontinued. Lung transplantation offers the only hope for cure despite reports of recurrent disease in the transplanted lung.

SYNDROMES OF ILD WITH DIFFUSE ALVEOLAR HEMORRHAGE

Clinical Manifestations The clinical onset is often abrupt, with cough, fever, and dyspnea. Severe respiratory distress requiring ventilatory support may be evident at initial presentation. Although hemoptysis is expected, it can be absent at the time of presentation in one-third of the cases. For patients without hemoptysis, new alveolar opacities, a falling hemoglobin level, and hemorrhagic BAL fluid point to the diagnosis. The chest radiograph is nonspecific and most commonly shows new patchy or diffuse alveolar opacities. Recurrent episodes of DAH may lead to pulmonary fibrosis, resulting in interstitial opacities on the chest radiograph. An elevated white blood cell count and falling hematocrit are common. Evidence for impaired renal function caused by focal segmental necrotizing glomerulonephritis, usually with crescent formation, also may be present. Varying degrees of hypoxemia may occur and are often severe enough to require ventilatory support. DLCO may be increased, resulting from the increased hemoglobin within the alveoli compartment.

Histologic Findings Injury to arterioles, venules, and the alveolar septal (alveolar wall or interstitial) capillaries can result in hemoptysis secondary to disruption of the alveolar-capillary basement membrane. This results in bleeding into the alveolar spaces, which characterizes DAH. Pulmonary capillaritis, characterized by a neutrophilic infiltration of the alveolar septae, may lead to necrosis of these structures, loss of capillary structural integrity, and the pouring of red blood cells into the alveolar space. Fibrinoid necrosis of the interstitium and red blood cells within the interstitial space are sometimes seen. Bland pulmonary hemorrhage (i.e., DAH without inflammation of the alveolar structures) also may occur.

Evaluation of either lung or renal tissue by immunofluorescent techniques indicates an absence of immune complexes (pauci-immune) in granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener), microscopic polyangiitis, pauci-immune glomerulonephritis, and isolated pulmonary capillaritis. A granular pattern is found in the CTDs, particularly SLE, and a characteristic linear deposition is found in Goodpasture syndrome. Granular deposition of IgA-containing immune complexes is present in Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

Treatment The mainstay of therapy for the DAH associated with systemic vasculitis, CTD, Goodpasture syndrome, and isolated pulmonary capillaritis is IV methylprednisolone, 0.5–2 g daily in divided doses for up to 5 days, followed by a gradual tapering, and then maintenance on an oral preparation. Prompt initiation of therapy is important, particularly in the face of renal insufficiency, because early initiation of therapy has the best chance of preserving renal function. The decision to start other immunosuppressive therapy (cyclophosphamide or azathioprine) acutely depends on the severity of illness.

Goodpasture Syndrome • CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS Pulmonary hemorrhage and glomerulonephritis are features in most patients with this disease. Autoantibodies to renal glomerular and lung alveolar basement membranes are present. This syndrome can present and recur as DAH without an associated glomerulonephritis. In such cases, circulating anti-basement membrane antibody is often absent, and the only way to establish the diagnosis is by demonstrating linear immunofluorescence in lung tissue.

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS The underlying histology may be bland hemorrhage or DAH associated with capillaritis.

TREATMENT Plasmapheresis has been recommended as adjunctive treatment.

INHERITED DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH ILD

Pulmonary opacities and respiratory symptoms typical of ILD can develop in related family members and in several inherited diseases. These diseases include the phakomatoses, tuberous sclerosis and neurofibromatosis (Chap. 118), and the lysosomal storage diseases, Niemann-Pick disease and Gaucher disease (Chap. 432e). The Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome is an autosomal recessive disorder in which granulomatous colitis and ILD may occur. It is characterized by oculocutaneous albinism, bleeding diathesis secondary to platelet dysfunction, and the accumulation of a chromolipid, lipofuscin material in cells of the reticuloendothelial system. A fibrotic pattern is found on lung biopsy, but the alveolar macrophages may contain cytoplasmic ceroid-like inclusions.

ILD WITH A GRANULOMATOUS RESPONSE IN LUNG TISSUE OR VASCULAR STRUCTURES

Inhalation of organic dusts, which cause hypersensitivity pneumonitis, or of inorganic dust, such as silica, which elicits a granulomatous inflammatory reaction leading to ILD, produces diseases of known etiology (Table 315-1) that are discussed in Chaps. 310 and 311. Sarcoidosis (Chap. 390) is prominent among granulomatous diseases of unknown cause in which ILD is an important feature.

Granulomatous Vasculitides (See also Chap. 385) The granulomatous vasculitides are characterized by pulmonary angiitis (i.e., inflammation and necrosis of blood vessels) with associated granuloma formation (i.e., infiltrates of lymphocytes, plasma cells, epithelioid cells, or histiocytes, with or without the presence of multinucleated giant cells, sometimes with tissue necrosis). The lungs are almost always involved, although any organ system may be affected. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener) and Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) primarily affect the lung but are associated with a systemic vasculitis as well. The granulomatous vasculitides generally limited to the lung include necrotizing sarcoid granulomatosis and benign lymphocytic angiitis and granulomatosis. Granulomatous infection and pulmonary angiitis due to irritating embolic material (e.g., talc) are important known causes of pulmonary vasculitis.

LYMPHOCYTIC INFILTRATIVE DISORDERS

This group of disorders features lymphocyte and plasma cell infiltration of the lung parenchyma. The disorders either are benign or can behave as low-grade lymphomas. Included is angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia, a rare lymphoproliferative disorder characterized by diffuse lymphadenopathy, fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and hemolytic anemia, with ILD in some cases.

Lymphocytic Interstitial Pneumonitis This rare form of ILD occurs in adults, some of whom have an autoimmune disease or dysproteinemia. It has been reported in patients with Sjögren syndrome and HIV infection.

Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis • CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS Pulmonary lymphomatoid granulomatosis generally presents predominantly in men between the ages of 30 and 50, although patients can be affected at any age. The effects of race and geography on disease incidence are not known, although a higher diagnosis rate is reported in Western countries. Although it may affect virtually any organ, it is most frequently characterized by pulmonary (>90%), skin, and central nervous system involvement. The most common presenting symptoms and signs include cough, fever, rash/nodules, malaise, weight loss, neurologic abnormalities, dyspnea, and chest pain.

HISTOLOGIC FINDINGS This multisystem disorder of unknown etiology is an angiocentric malignant (T cell) lymphoma characterized by a polymorphic lymphoid infiltrate, an angiitis, and granulomatosis.

TREATMENT The clinical course of lymphomatoid granulomatosis ranges from remission without treatment to death from malignant lymphoma within 2 years. The choice of a treatment strategy should be based upon the presence of symptoms, history of using an inciting medication, extent of extrapulmonary involvement, and careful assessment of the histopathologic grade of the lesion. Referral to a hematology oncology specialist for consultation is recommended.

BRONCHOCENTRIC GRANULOMATOSIS

Clinical Manifestations Rather than a specific clinical entity, bronchocentric granulomatosis (BG) is a descriptive histologic term that is applied to an uncommon and nonspecific pathologic response to a variety of airway injuries. There is evidence that BG is caused by a hypersensitivity reaction to Aspergillus or other fungi in patients with asthma. About one-half of the patients described have had chronic asthma with severe wheezing and peripheral blood eosinophilia. In patients with asthma, BG probably represents one pathologic manifestation of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis or another allergic mycosis. In patients without asthma, BG has been associated with RA and a variety of infections, including tuberculosis, echinococcosis, histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis, and nocardiosis. The chest roentgenogram reveals irregularly shaped nodular or mass lesions with ill-defined margins, which are usually unilateral and solitary, with upper lobe predominance.

Histologic Findings Bronchocentric granulomatosis is characterized by peribronchial and peribronchiolar necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. Destruction of airway walls and adjacent parenchyma leads to granulomatous replacement of mucosa and submucosa by palisading, epithelioid, and multinucleated histiocytes. Bronchocentric granulomatosis does not typically involve the pulmonary arteries.

Treatment Glucocorticoids are the treatment of choice, often with an excellent outcome, although recurrences may occur as therapy is tapered or stopped.

GLOBAL CONSIDERATIONS

![]() Limited epidemiologic data exist describing the prevalence or incidence of ILD in the general population. With a few exceptions, e.g., sarcoidosis and certain occupational and environmental exposures, there appear to be no significant differences in the prevalence or incidence of ILD among various populations. For sarcoidosis, there are important environmental, racial, and genetic differences (Chap. 390).

Limited epidemiologic data exist describing the prevalence or incidence of ILD in the general population. With a few exceptions, e.g., sarcoidosis and certain occupational and environmental exposures, there appear to be no significant differences in the prevalence or incidence of ILD among various populations. For sarcoidosis, there are important environmental, racial, and genetic differences (Chap. 390).

316 |

Disorders of the Pleura |

PLEURAL EFFUSION

The pleural space lies between the lung and the chest wall and normally contains a very thin layer of fluid, which serves as a coupling system. A pleural effusion is present when there is an excess quantity of fluid in the pleural space.

Etiology Pleural fluid accumulates when pleural fluid formation exceeds pleural fluid absorption. Normally, fluid enters the pleural space from the capillaries in the parietal pleura and is removed via the lymphatics in the parietal pleura. Fluid also can enter the pleural space from the interstitial spaces of the lung via the visceral pleura or from the peritoneal cavity via small holes in the diaphragm. The lymphatics have the capacity to absorb 20 times more fluid than is formed normally. Accordingly, a pleural effusion may develop when there is excess pleural fluid formation (from the interstitial spaces of the lung, the parietal pleura, or the peritoneal cavity) or when there is decreased fluid removal by the lymphatics.

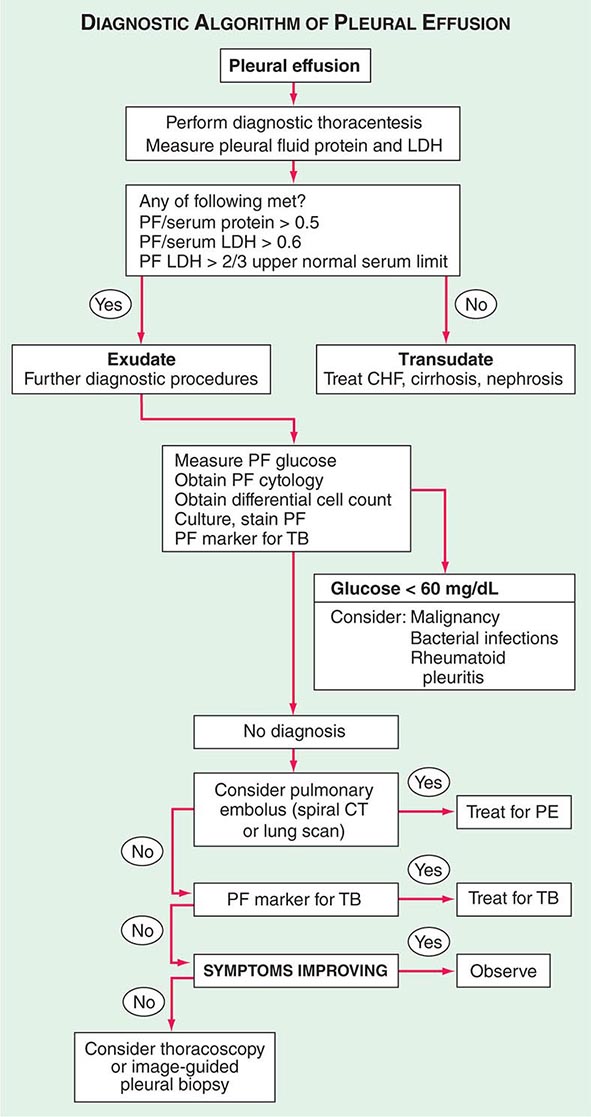

Diagnostic Approach Patients suspected of having a pleural effusion should undergo chest imaging to diagnose its extent. Chest ultrasound has replaced the lateral decubitus x-ray in the evaluation of suspected pleural effusions and as a guide to thoracentesis. When a patient is found to have a pleural effusion, an effort should be made to determine the cause (Fig. 316-1). The first step is to determine whether the effusion is a transudate or an exudate. A transudative pleural effusion occurs when systemic factors that influence the formation and absorption of pleural fluid are altered. The leading causes of transudative pleural effusions in the United States are left ventricular failure and cirrhosis. An exudative pleural effusion occurs when local factors that influence the formation and absorption of pleural fluid are altered. The leading causes of exudative pleural effusions are bacterial pneumonia, malignancy, viral infection, and pulmonary embolism. The primary reason for making this differentiation is that additional diagnostic procedures are indicated with exudative effusions to define the cause of the local disease.

FIGURE 316-1 Approach to the diagnosis of pleural effusions. CHF, congestive heart failure; CT, computed tomography; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PE, pulmonary embolism; PF, pleural fluid; TB, tuberculosis.

Transudative and exudative pleural effusions are distinguished by measuring the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and protein levels in the pleural fluid. Exudative pleural effusions meet at least one of the following criteria, whereas transudative pleural effusions meet none:

1. Pleural fluid protein/serum protein >0.5

2. Pleural fluid LDH/serum LDH >0.6

3. Pleural fluid LDH more than two-thirds the normal upper limit for serum

These criteria misidentify ~25% of transudates as exudates. If one or more of the exudative criteria are met and the patient is clinically thought to have a condition producing a transudative effusion, the difference between the protein levels in the serum and the pleural fluid should be measured. If this gradient is >31 g/L (3.1 g/dL), the exudative categorization by these criteria can be ignored because almost all such patients have a transudative pleural effusion.

If a patient has an exudative pleural effusion, the following tests on the pleural fluid should be obtained: description of the appearance of the fluid, glucose level, differential cell count, microbiologic studies, and cytology.

Effusion Due to Heart Failure The most common cause of pleural effusion is left ventricular failure. The effusion occurs because the increased amounts of fluid in the lung interstitial spaces exit in part across the visceral pleura; this overwhelms the capacity of the lymphatics in the parietal pleura to remove fluid. In patients with heart failure, a diagnostic thoracentesis should be performed if the effusions are not bilateral and comparable in size, if the patient is febrile, or if the patient has pleuritic chest pain to verify that the patient has a transudative effusion. Otherwise the patient’s heart failure is treated. If the effusion persists despite therapy, a diagnostic thoracentesis should be performed. A pleural fluid N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) >1500 pg/mL is virtually diagnostic that the effusion is secondary to congestive heart failure.

Hepatic Hydrothorax Pleural effusions occur in ~5% of patients with cirrhosis and ascites. The predominant mechanism is the direct movement of peritoneal fluid through small openings in the diaphragm into the pleural space. The effusion is usually right-sided and frequently is large enough to produce severe dyspnea.

Parapneumonic Effusion Parapneumonic effusions are associated with bacterial pneumonia, lung abscess, or bronchiectasis and are probably the most common cause of exudative pleural effusion in the United States. Empyema refers to a grossly purulent effusion.

Patients with aerobic bacterial pneumonia and pleural effusion present with an acute febrile illness consisting of chest pain, sputum production, and leukocytosis. Patients with anaerobic infections present with a subacute illness with weight loss, a brisk leukocytosis, mild anemia, and a history of some factor that predisposes them to aspiration.

The possibility of a parapneumonic effusion should be considered whenever a patient with bacterial pneumonia is initially evaluated. The presence of free pleural fluid can be demonstrated with a lateral decubitus radiograph, computed tomography (CT) of the chest, or ultrasound. If the free fluid separates the lung from the chest wall by >10 mm, a therapeutic thoracentesis should be performed. Factors indicating the likely need for a procedure more invasive than a thoracentesis (in increasing order of importance) include the following:

1. Loculated pleural fluid

2. Pleural fluid pH <7.20

3. Pleural fluid glucose <3.3 mmol/L (<60 mg/dL)

4. Positive Gram stain or culture of the pleural fluid

5. Presence of gross pus in the pleural space

If the fluid recurs after the initial therapeutic thoracentesis and if any of these characteristics are present, a repeat thoracentesis should be performed. If the fluid cannot be completely removed with the therapeutic thoracentesis, consideration should be given to inserting a chest tube and instilling the combination of a fibrinolytic agent (e.g., tissue plasminogen activator, 10 mg) and deoxyribonuclease (5 mg) or performing a thoracoscopy with the breakdown of adhesions. Decortication should be considered when these measures are ineffective.

Effusion Secondary to Malignancy Malignant pleural effusions secondary to metastatic disease are the second most common type of exudative pleural effusion. The three tumors that cause ~75% of all malignant pleural effusions are lung carcinoma, breast carcinoma, and lymphoma. Most patients complain of dyspnea, which is frequently out of proportion to the size of the effusion. The pleural fluid is an exudate, and its glucose level may be reduced if the tumor burden in the pleural space is high.

The diagnosis usually is made via cytology of the pleural fluid. If the initial cytologic examination is negative, thoracoscopy is the best next procedure if malignancy is strongly suspected. At the time of thoracoscopy, a procedure such as pleural abrasion should be performed to effect a pleurodesis. An alternative to thoracoscopy is CT- or ultrasound-guided needle biopsy of pleural thickening or nodules. Patients with a malignant pleural effusion are treated symptomatically for the most part, since the presence of the effusion indicates disseminated disease and most malignancies associated with pleural effusion are not curable with chemotherapy. The only symptom that can be attributed to the effusion itself is dyspnea. If the patient’s lifestyle is compromised by dyspnea and if the dyspnea is relieved with a therapeutic thoracentesis, one of the following procedures should be considered: (1) insertion of a small indwelling catheter or (2) tube thoracostomy with the instillation of a sclerosing agent such as doxycycline (500 mg).

Mesothelioma Malignant mesotheliomas are primary tumors that arise from the mesothelial cells that line the pleural cavities; most are related to asbestos exposure. Patients with mesothelioma present with chest pain and shortness of breath. The chest radiograph reveals a pleural effusion, generalized pleural thickening, and a shrunken hemithorax. The diagnosis is usually established with image-guided needle biopsy or thoracoscopy.

Effusion Secondary to Pulmonary Embolization The diagnosis most commonly overlooked in the differential diagnosis of a patient with an undiagnosed pleural effusion is pulmonary embolism. Dyspnea is the most common symptom. The pleural fluid is almost always an exudate. The diagnosis is established by spiral CT scan or pulmonary arteriography (Chap. 300). Treatment of a patient with a pleural effusion secondary to pulmonary embolism is the same as it is for any patient with pulmonary emboli. If the pleural effusion increases in size after anticoagulation, the patient probably has recurrent emboli or another complication, such as a hemothorax or a pleural infection.

Tuberculous Pleuritis (See also Chap. 202) In many parts of the world, the most common cause of an exudative pleural effusion is tuberculosis (TB), but tuberculous effusions are relatively uncommon in the United States. Tuberculous pleural effusions usually are associated with primary TB and are thought to be due primarily to a hypersensitivity reaction to tuberculous protein in the pleural space. Patients with tuberculous pleuritis present with fever, weight loss, dyspnea, and/or pleuritic chest pain. The pleural fluid is an exudate with predominantly small lymphocytes. The diagnosis is established by demonstrating high levels of TB markers in the pleural fluid (adenosine deaminase >40 IU/L or interferon γ >140 pg/mL). Alternatively, the diagnosis can be established by culture of the pleural fluid, needle biopsy of the pleura, or thoracoscopy. The recommended treatments of pleural and pulmonary TB are identical (Chap. 202).

Effusion Secondary to Viral Infection Viral infections are probably responsible for a sizable percentage of undiagnosed exudative pleural effusions. In many series, no diagnosis is established for ~20% of exudative effusions, and these effusions resolve spontaneously with no long-term residua. The importance of these effusions is that one should not be too aggressive in trying to establish a diagnosis for the undiagnosed effusion, particularly if the patient is improving clinically.

Chylothorax A chylothorax occurs when the thoracic duct is disrupted and chyle accumulates in the pleural space. The most common cause of chylothorax is trauma (most frequently thoracic surgery), but it also may result from tumors in the mediastinum. Patients with chylothorax present with dyspnea, and a large pleural effusion is present on the chest radiograph. Thoracentesis reveals milky fluid, and biochemical analysis reveals a triglyceride level that exceeds 1.2 mmol/L (110 mg/dL). Patients with chylothorax and no obvious trauma should have a lymphangiogram and a mediastinal CT scan to assess the mediastinum for lymph nodes. The treatment of choice for most chylothoraxes is insertion of a chest tube plus the administration of octreotide. If these modalities fail, a pleuroperitoneal shunt should be placed unless the patient has chylous ascites. Alternative treatments are ligation of the thoracic duct and percutaneous transabdominal thoracic duct blockage. Patients with chylothoraxes should not undergo prolonged tube thoracostomy with chest tube drainage because this will lead to malnutrition and immunologic incompetence.

Hemothorax When a diagnostic thoracentesis reveals bloody pleural fluid, a hematocrit should be obtained on the pleural fluid. If the hematocrit is more than one-half of that in the peripheral blood, the patient is considered to have a hemothorax. Most hemothoraxes are the result of trauma; other causes include rupture of a blood vessel or tumor. Most patients with hemothorax should be treated with tube thoracostomy, which allows continuous quantification of bleeding. If the bleeding emanates from a laceration of the pleura, apposition of the two pleural surfaces is likely to stop the bleeding. If the pleural hemorrhage exceeds 200 mL/h, consideration should be given to thoracoscopy or thoracotomy.

Miscellaneous Causes of Pleural Effusion There are many other causes of pleural effusion (Table 316-1). Key features of some of these conditions are as follows: If the pleural fluid amylase level is elevated, the diagnosis of esophageal rupture or pancreatic disease is likely. If the patient is febrile, has predominantly polymorphonuclear cells in the pleural fluid, and has no pulmonary parenchymal abnormalities, an intraabdominal abscess should be considered.

|

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES OF PLEURAL EFFUSIONS |

The diagnosis of an asbestos pleural effusion is one of exclusion. Benign ovarian tumors can produce ascites and a pleural effusion (Meigs’ syndrome), as can the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Several drugs can cause pleural effusion; the associated fluid is usually eosinophilic. Pleural effusions commonly occur after coronary artery bypass surgery. Effusions occurring within the first weeks are typically left-sided and bloody, with large numbers of eosinophils, and respond to one or two therapeutic thoracenteses. Effusions occurring after the first few weeks are typically left-sided and clear yellow, with predominantly small lymphocytes, and tend to recur. Other medical manipulations that induce pleural effusions include abdominal surgery; radiation therapy; liver, lung, or heart transplantation; and the intravascular insertion of central lines.

PNEUMOTHORAX

Pneumothorax is the presence of gas in the pleural space. A spontaneous pneumothorax is one that occurs without antecedent trauma to the thorax. A primary spontaneous pneumothorax occurs in the absence of underlying lung disease, whereas a secondary pneumothorax occurs in its presence. A traumatic pneumothorax results from penetrating or nonpenetrating chest injuries. A tension pneumothorax is a pneumothorax in which the pressure in the pleural space is positive throughout the respiratory cycle.

Primary Spontaneous Pneumothorax Primary spontaneous pneumothoraxes are usually due to rupture of apical pleural blebs, small cystic spaces that lie within or immediately under the visceral pleura. Primary spontaneous pneumothoraxes occur almost exclusively in smokers; this suggests that these patients have subclinical lung disease. Approximately one-half of patients with an initial primary spontaneous pneumothorax will have a recurrence. The initial recommended treatment for primary spontaneous pneumothorax is simple aspiration. If the lung does not expand with aspiration or if the patient has a recurrent pneumothorax, thoracoscopy with stapling of blebs and pleural abrasion is indicated. Thoracoscopy or thoracotomy with pleural abrasion is almost 100% successful in preventing recurrences.

Secondary Pneumothorax Most secondary pneumothoraxes are due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, but pneumothoraxes have been reported with virtually every lung disease. Pneumothorax in patients with lung disease is more life-threatening than it is in normal individuals because of the lack of pulmonary reserve in these patients. Nearly all patients with secondary pneumothorax should be treated with tube thoracostomy. Most should also be treated with thoracoscopy or thoracotomy with the stapling of blebs and pleural abrasion. If the patient is not a good operative candidate or refuses surgery, pleurodesis should be attempted by the intrapleural injection of a sclerosing agent such as doxycycline.

Traumatic Pneumothorax Traumatic pneumothoraxes can result from both penetrating and nonpenetrating chest trauma. Traumatic pneumothoraxes should be treated with tube thoracostomy unless they are very small. If a hemopneumothorax is present, one chest tube should be placed in the superior part of the hemithorax to evacuate the air and another should be placed in the inferior part of the hemithorax to remove the blood. Iatrogenic pneumothorax is a type of traumatic pneumothorax that is becoming more common. The leading causes are transthoracic needle aspiration, thoracentesis, and the insertion of central intravenous catheters. Most can be managed with supplemental oxygen or aspiration, but if these measures are unsuccessful, a tube thoracostomy should be performed.

Tension Pneumothorax This condition usually occurs during mechanical ventilation or resuscitative efforts. The positive pleural pressure is life-threatening both because ventilation is severely compromised and because the positive pressure is transmitted to the mediastinum, resulting in decreased venous return to the heart and reduced cardiac output.

Difficulty in ventilation during resuscitation or high peak inspiratory pressures during mechanical ventilation strongly suggest the diagnosis. The diagnosis is made by physical examination showing an enlarged hemithorax with no breath sounds, hyperresonance to percussion, and shift of the mediastinum to the contralateral side. Tension pneumothorax must be treated as a medical emergency. If the tension in the pleural space is not relieved, the patient is likely to die from inadequate cardiac output or marked hypoxemia. A large-bore needle should be inserted into the pleural space through the second anterior intercostal space. If large amounts of gas escape from the needle after insertion, the diagnosis is confirmed. The needle should be left in place until a thoracostomy tube can be inserted.

317 |

Disorders of the Mediastinum |

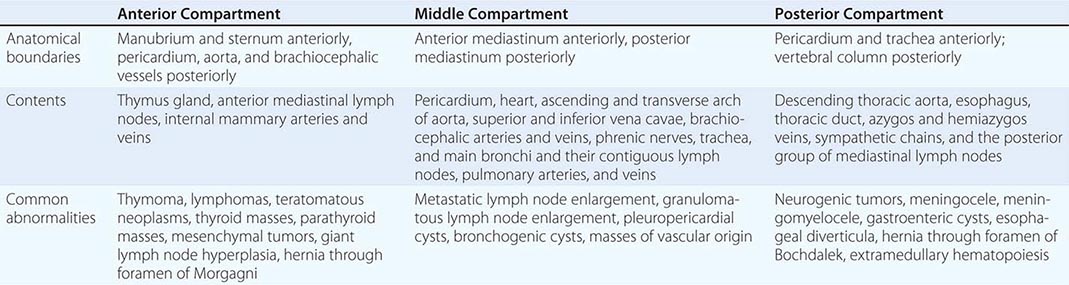

The mediastinum is the region between the pleural sacs. It is separated into three compartments (Table 317-1). The anterior mediastinum extends from the sternum anteriorly to the pericardium and brachiocephalic vessels posteriorly. It contains the thymus gland, the anterior mediastinal lymph nodes, and the internal mammary arteries and veins. The middle mediastinum lies between the anterior and posterior mediastina and contains the heart; the ascending and transverse arches of the aorta; the venae cavae; the brachiocephalic arteries and veins; the phrenic nerves; the trachea, the main bronchi, and their contiguous lymph nodes; and the pulmonary arteries and veins. The posterior mediastinum is bounded by the pericardium and trachea anteriorly and the vertebral column posteriorly. It contains the descending thoracic aorta, the esophagus, the thoracic duct, the azygos and hemiazygos veins, and the posterior group of mediastinal lymph nodes.

|

THE THREE COMPARTMENTS OF THE MEDIASTINUM |

MEDIASTINAL MASSES

The first step in evaluating a mediastinal mass is to place it in one of the three mediastinal compartments, since each has different characteristic lesions (Table 317-1). The most common lesions in the anterior mediastinum are thymomas, lymphomas, teratomatous neoplasms, and thyroid masses. The most common masses in the middle mediastinum are vascular masses, lymph node enlargement from metastases or granulomatous disease, and pleuropericardial and bronchogenic cysts. In the posterior mediastinum, neurogenic tumors, meningoceles, meningomyeloceles, gastroenteric cysts, and esophageal diverticula are commonly found.

Computed tomography (CT) scanning is the most valuable imaging technique for evaluating mediastinal masses and is the only imaging technique that should be done in most instances. Barium studies of the gastrointestinal tract are indicated in many patients with posterior mediastinal lesions, because hernias, diverticula, and achalasia are readily diagnosed in this manner. An iodine-131 scan can efficiently establish the diagnosis of intrathoracic goiter.

A definite diagnosis can be obtained with mediastinoscopy or anterior mediastinotomy in many patients with masses in the anterior or middle mediastinal compartments. A diagnosis can be established without thoracotomy via percutaneous fine-needle aspiration biopsy or endoscopic transesophageal or endobronchial ultrasound-guided biopsy of mediastinal masses in most cases. An alternative way to establish the diagnosis is video-assisted thoracoscopy. In many cases, the diagnosis can be established and the mediastinal mass removed with video-assisted thoracoscopy.

ACUTE MEDIASTINITIS

Most cases of acute mediastinitis either are due to esophageal perforation or occur after median sternotomy for cardiac surgery. Patients with esophageal rupture are acutely ill with chest pain and dyspnea due to the mediastinal infection. The esophageal rupture can occur spontaneously or as a complication of esophagoscopy or the insertion of a Blakemore tube. Appropriate treatment consists of exploration of the mediastinum with primary repair of the esophageal tear and drainage of the pleural space and the mediastinum.

The incidence of mediastinitis after median sternotomy is 0.4–5.0%. Patients most commonly present with wound drainage. Other presentations include sepsis and a widened mediastinum. The diagnosis usually is established with mediastinal needle aspiration. Treatment includes immediate drainage, debridement, and parenteral antibiotic therapy, but the mortality rate still exceeds 20%.

CHRONIC MEDIASTINITIS

The spectrum of chronic mediastinitis ranges from granulomatous inflammation of the lymph nodes in the mediastinum to fibrosing mediastinitis. Most cases are due to histoplasmosis or tuberculosis, but sarcoidosis, silicosis, and other fungal diseases are at times causative. Patients with granulomatous mediastinitis are usually asymptomatic. Those with fibrosing mediastinitis usually have signs of compression of a mediastinal structure such as the superior vena cava or large airways, phrenic or recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis, or obstruction of the pulmonary artery or proximal pulmonary veins. Other than antituberculous therapy for tuberculous mediastinitis, no medical or surgical therapy has been demonstrated to be effective for mediastinal fibrosis.

PNEUMOMEDIASTINUM

In this condition, there is gas in the interstices of the mediastinum. The three main causes are (1) alveolar rupture with dissection of air into the mediastinum; (2) perforation or rupture of the esophagus, trachea, or main bronchi; and (3) dissection of air from the neck or the abdomen into the mediastinum. Typically, there is severe substernal chest pain with or without radiation into the neck and arms. The physical examination usually reveals subcutaneous emphysema in the suprasternal notch and Hamman’s sign, which is a crunching or clicking noise synchronous with the heartbeat and is best heard in the left lateral decubitus position. The diagnosis is confirmed with the chest radiograph. Usually no treatment is required, but the mediastinal air will be absorbed faster if the patient inspires high concentrations of oxygen. If mediastinal structures are compressed, the compression can be relieved with needle aspiration.

318 |

Disorders of Ventilation |

DEFINITION AND PHYSIOLOGY

In health the arterial level of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) IS maintained between 37 and 43 mmHg at sea level. All disorders of ventilation result in abnormal measurements of PaCO2. This chapter reviews chronic ventilatory disorders.

The continuous production of CO2 by cellular metabolism necessitates its efficient elimination by the respiratory system. The relationship between CO2 production and PaCO2 is described by the equation: PaCO2 = (k) (![]() CO2)/

CO2)/![]() A, where

A, where ![]() CO2 represents the carbon dioxide production, k is a constant, and

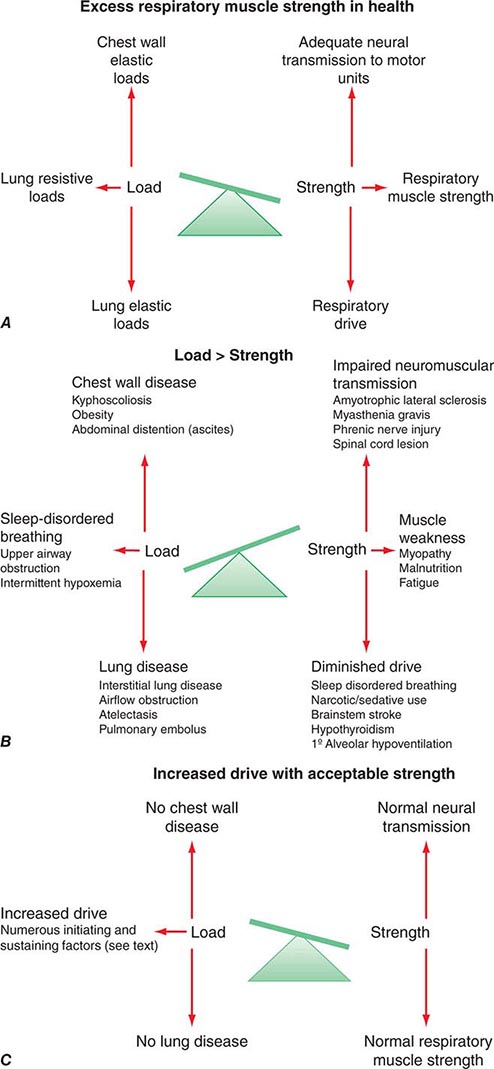

CO2 represents the carbon dioxide production, k is a constant, and ![]() A is fresh gas alveolar ventilation (Chap. 306e).