30 Sleep and Insomnia

Since antiquity, sleep has been considered a time of healing, mending, and restoration.1 Sleeping difficulties are a significant issue for many healthy children and adolescents and are further increased in children suffering from life-threatening conditions. This can have a significant impact on both the child and his or her family. Lack of restful sleep can lead to impaired daytime functioning, increased pain, mood disturbances, altered immune function, and school or work problems for both children and parents.2–3 Sleep also provides an important respite for children with life-threatening conditions and their parents from the daily burden associated with managing their conditions.4

Classification of Sleeping Problems in Childhood

Sleep problems for children and adolescents can include:

Growth and Development

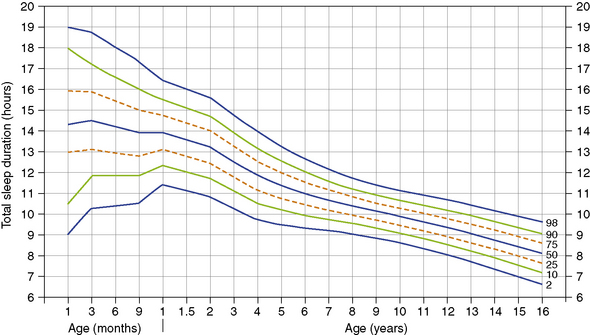

An understanding of normal developmental changes in children’s sleep patterns is helpful for both practitioners and families. Regular sleeping patterns generally become established by 12 months of age. Total sleep duration decreases from an average of 14.2 hours at 6 months of age to an average of 8.1 hours at 16 years of age10 (Fig. 30-1). There is a decreasing trend for daytime napping beyond the age of 12 months, with the most prominent decline in napping habits occurring between 18 months and 4 years of age.10 There is also a trend for children, particularly adolescents, to go to sleep at a later time compared with earlier eras, and this can be attributed to academic demands and entertainment, such as the Internet and television.10–12

Sleeping Difficulties in Healthy Children

Sleeping problems occur in healthy children. It has been found that 24% of children between 1 and 2 years still wake regularly at night.13 The frequency of disrupted sleep at night continues to decrease with age, with 10% of children waking at age 8.14 Sleeping problems are also important for adolescents, with 10% to 15% having difficulties falling asleep.14 Erratic sleeping patterns, partly associated with hormone secretion related to puberty, can make it difficult for some adolescents to fall asleep at bedtime. While nearly all teenagers show this tendency toward delayed sleep onset, approximately 7% will be diagnosed with delayed sleep phase syndrome in which the adolescent is typically unable to fall asleep before midnight and has extreme difficulty waking up in the morning.15 A national survey of 70,000 healthy children in the United States aged between 6 and 18 years showed 31.9% experienced more than one night of inadequate sleep in the week before the survey.16

Children with Life-Threatening Conditions

Sleep problems are magnified in children with respiratory, metabolic, neurologic, and malignant conditions. Insomnia can be considered a symptom in this group of children rather than a diagnosis. The cause may be peripheral in origin, such as gastroesophageal reflux causing pain or adenoidal hypertrophy with nasal obstruction causing respiratory difficulty. Alternatively, the causes of poor sleep may be central in origin, related to medications, brain tumors, seizures, and syndrome abnormalities with dysfunction of central sleep systems.17 In particular, pain and sleep-disordered breathing are prevalent problems in this patient population. Sleeping difficulties have also been noted to be present in children receiving end-of-life care.

Sleep complaints are common in children and adolescents diagnosed with cystic fibrosis (CF) with approximately 40% of children reporting difficulty falling asleep and a similar proportion having difficulty staying asleep.18 Hypoxemia and nocturnal cough account for some of these difficulties.19,20 Various metabolic and genetic syndromes are also associated with sleep disturbance, including Rett syndrome and Angelmann syndrome.21,22 Approximately 90% of children diagnosed with Sanfilippo syndrome have sleep disturbance.23

Structural brain lesions in infants and children are also often associated with difficulty falling asleep at night and nocturnal awakenings.24 States of wakefulness are regulated by brainstem nuclei, while the establishment of circadian rhythms is dependent upon the hypothalamus and its connections. Children with midline brain pathology and blindness are at high risk for sleep disorders resulting from desynchronization of the 24-hour sleep-wake rhythm. Children with hydranencephaly, in particular, can suffer from severe sleep disturbance, demonstrating the importance that intact cerebral hemispheres have in maintaining sleep-wake cycles.

Sleep-disordered breathing can occur in patients with chronic respiratory illnesses such as chest wall, neuromuscular, primary lung diseases and heart failure. Obstructive sleep apnea in children can be caused by enlarged tonsils or adenoids. Obesity, severe scoliosis, and craniofacial deformities may also contribute to sleep-related breathing problems.19 All of these risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing occur in children with life-threatening conditions.

Central and obstructive apneas are common and problematic for children with myopathies and other neuromuscular disease. Respiratory disorders during sleep, including apnea and hypoventilation, have been described in Duchenne muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy.19,24 Such children can experience ventilatory muscle fatigue, particularly in the latter hours of the night, resulting in disrupted sleep, daytime sleepiness, and headaches. Excessive daytime sleepiness was also a common sleep disturbance in children with brain tumors.25 Problems included resumption of daytime naps, difficulty waking in the morning, and inability to remain awake during daytime activities such as school.

Approximately 31% of children with cancer treated as outpatients experienced sleeping difficulties.26,27 This symptom was particularly distressing to 39% of 7- to 12-year-old children while 59% of 10- to 18-year-old children found this symptom to be particularly distressing. Children with cancer who are admitted to hospital for chemotherapy sleep for a longer duration and have more frequently disrupted sleep.28 One study revealed that 80% of children with cancer experienced significant pain at the time of their diagnosis. Almost 75% of children reported that this pain led to sleep disruption.29 The disruption of the sleep-wake pattern is a common issue adding to the fatigue that often accompanies cancer and its treatments.30

A survey of children attending a chronic pain clinic found that 71% had sleep disruptions.31 Pain has been found to contribute to children waking from sleep and affecting the overall quality of sleep in a number of studies.32,33 Pain may interfere with the ability to sleep because it can fragment sleep with frequent awakening, activate threat-related arousal to more pain, and increase vigilance that something worse may happen.34,35 Pain and discomfort affect sleep, while poor sleep predisposes a patient to increased, pain experiences.35,36 A study of healthy young adults found that reduced sleep led to increased sensitivity to pain.37 A bidirectional relationship between pain and sleep may ensue such that children enter a negative downward spiral in which worsening pain disrupts sleep, which then further heightens their pain experience.

Retrospective studies of children who died found insomnia to occur in 20% to 25% of children in the terminal stage of their disease.38,39 Fatigue is the most common symptom experienced at the end of life.39,40 Fatigue in children with cancer has been found to negatively correlate with sleep quality.28 Although anemia and metabolic changes may contribute to fatigue, sleeping poorly at night may be another important factor.34 Further, medications used to treat symptoms, such as opioid analgesics, antiepileptic drugs, and benzodiazapines, and keep children comfortable can also disrupt normal sleep patterns.41,42 Assessment can be difficult in the palliative care context where fatigue and sleepiness can arise from the disease state as well as sleep disturbance.

Effect of Hospitalization on Sleep

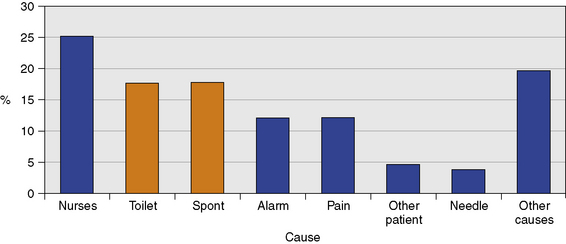

One survey of children ages 3 to 8 years who were admitted to a general pediatric unit found that they lost 20% to 25% of their usual sleep time.43,44 Children admitted to intensive care lost up to 50% of their sleeping time. These changes in sleep, such as reversal of the sleep-wake cycle, can persist for up to 7 weeks after discharge from the intensive care unit.45 A survey of children and adolescents admitted to The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, Australia, found that the overall prevalence of poor sleep in children admitted to hospital was 52%.32 This survey included children with malignant and non-malignant life-threatening conditions, 19 and 11% of sample, respectively. The causes that woke children, in this survey, are presented in Fig. 30-2.

Sleep loss in the hospital is due to the underlying disease as well as environmental and psychosocial aspects associated with hospital admission.35 Many factors contribute to disturbed sleep, including noise, lights, lack of control, separation from parents, unfamiliar environment, loss of normal routine, anxiety, depression, and pain.28,44,46 Children may also have negative associations with their hospital bed if it is linked with stressors such as pain or procedures.

These studies highlight the benefits of home care in the palliative care context, given the numerous hospital related factors that disrupt sleep in children. Nevertheless, some children receiving palliative care will still require admission to the hospital at times for symptom management, respite, and end-of-life care.47 It is therefore important for hospital environments to be conducive to sleep for children, siblings, and parents in this context.

Psychosocial Factors

Although sleep is a physiologic process, it occurs in a psychosocial context. Psychological stressors that hinder sleep onset, such as anxiety, are common in pediatric palliative care. Other psychosocial factors known to impact sleep include parental education, family stress, and cultural factors.14,48 Children themselves may have worries about their clinical status, their situation, and fears of the dark compounded by legitimate fears of death. Fear, anxiety, depression, and anger at bedtime may make it difficult for the child to transition smoothly to sleep both at bedtime and at subsequent awakenings throughout the night. For the transition to sleep to be smooth, a child must feel safe.

Both research and clinical experience supports a relationship between childhood sleep problems and anxiety and other alterations in mood. Even modest amounts of sleep restriction result in difficulties regulating emotion and subsequent elevations in anxiety and depression.49 Sleep problems are commonly associated with anxiety with as much as 83% of anxious children experiencing significant sleep disturbance.50 Difficulty falling asleep, refusing to sleep alone, and nightmares are common, along with reduced total sleep time on school nights, frequent nighttime waking, and decreased deep sleep.50–52

The link between anxiety and sleep disturbance is both biological and behavioral. From a biological perspective, anxiety is characterized by dysregulation in the Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in increased secretion of cortisol which may negatively impact the timing and patterns of children’s sleep. Anxious children have been found to secrete higher levels of cortisol during the pre-sleep period than depressed and healthy controls.53 Children with anxiety may also elicit parenting responses that inadvertently maintain their sleep problems. Parents of anxious children frequently respond to their child’s anxiety by over-protecting and enabling avoidance, which inadvertently maintains anxiety by limiting opportunities for children to test their fearful predictions and develop coping skills.54,55 Parent-child interactions are similarly important in maintaining childhood sleep problems. Studies show that children who require or receive a high level of parental involvement at bedtime are more likely to have night-waking problems and vice versa.56 Thus, the interaction between anxiety, sleep problems and parent-child bedtime interactions may be particularly complex in the palliative care context.

Sleep problems are similarly associated with depression in young people. Sleep disturbances are reported in up to 90% of adolescents with major depression.57 Depression in young people tends to be associated with symptoms of insomnia, with polysomnogram (PSG) studies revealing reduced total sleep time, longer sleep onset latencies and shorter latency to REM sleep.58 Poor sleep quality and daytime sleepiness are also frequently reported.59 At times it can be unclear whether the sleep or the emotional disturbance is the primary problem. Traditionally, disturbed sleep has been viewed as a manifestation or symptom of psychological disorder. Increasingly, however, there is evidence of a bidirectional relationship between sleep and emotional and behavioral functioning. It also has a huge impact on the emotional status of the family who looks after the child. Parents and caretakers at night need rest and sleep to continue the taxing nature of caring for children on a daily basis.

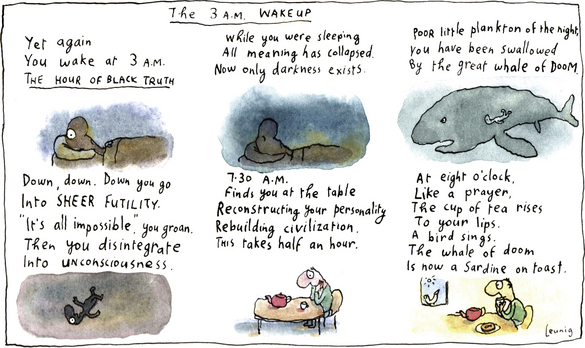

Adolescents with a life-threatening illness will also have concerns related to growing up and planning for the future combined with a grief relating to multiple losses, including changes in friendships, physical appearance, and modification of future aspirations. Supportive communication with their parents may be lacking, and as a consequence they may stay in bed, awake, trying to deal with poorly understood anxieties.60 As the cartoon (Fig. 30-3) “3 am Wakeup” illustrates, it can be difficult for health professionals to fully appreciate the impact of a disturbed night’s sleep, particularly when we observe and assess patients in the light of day. Worries may occur at night when in a dark room and defenses are least able to cope. Sometimes as health professionals we may minimize sleeping difficulties and see it like a “sardine on toast,” while our patients see it as a “great whale of doom.” There is also a spiritual dimension to this distress (Fig. 30-4).

Assessment

It is important to undertake a thorough history and examination when assessing a child with sleeping difficulties. If children are fully awake for long periods at night and miserable despite being held, walked or fed, offered playtime, or brought into the parents’ bed, medical causes such as pain and cerebral irritability should be considered.17 Older children and adolescents are able to recall whether their sleep was restful and refreshing or restless and disturbed. In younger children, the parent acts as proxy. A simple and effective subjective method of rating sleep is that of a visual analogue scale —a 100-mm horizontal line with opposing statements such as “best sleep ever” and “worst night ever” at each end. The subject being assessed is asked to place a mark on the line in a position corresponding to their perception of the previous night’s sleep. The distance of that mark along the line may then be measured in millimeters, providing a numerical value for satisfaction with the previous night’s sleep. Each subject creates his or her own scale, which is extremely sensitive to change and therefore particularly useful for serial assessments.61

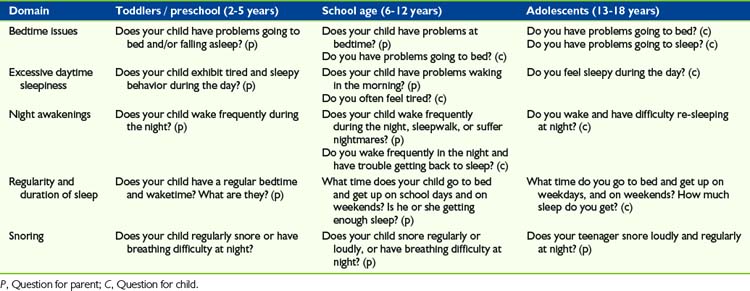

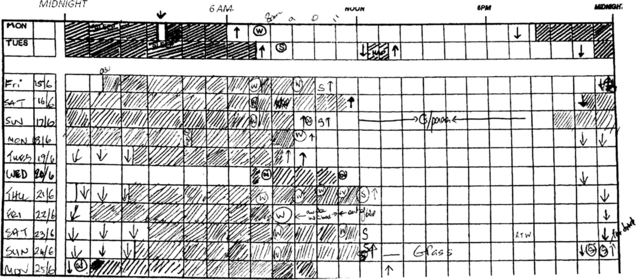

BEARS (Bedtime issues, Excessive daytime sleepiness, night Awakenings, Regularity and duration of sleep, Snoring) is a five-item pediatric sleep screening instrument that is useful in obtaining sleep-related information and identifying sleep problems and can be incorporated into taking a sleep history from a child or parent62 (Table 30-1). A sleep diary is another assessment tool that allows parents or older children to record periods of being asleep and being awake over a 24-hour period. There are also provisions to record the times, duration, and causes of awakenings throughout the night. Sleep diaries completed by parents are an accurate way of measuring sleep-schedule measures, that is sleep duration and sleep onset time, and can be completed over a number of days. It is often necessary for parents to complete sleep diaries on their child’s behalf, particularly where the child may still be developing an accurate sense of time. Children older than 12 years can accurately and reliably complete a sleep diary themselves63 (Fig. 30-5). Online sleep diaries are also available.51

An actigraph monitor is a small, lightweight, and watch-like device attached to the wrist and is capable of collecting time-based activity data over extended intervals. It is the gold standard to which sleep diaries are compared. Parents can overestimate the time their children spend in actual sleep and underestimate the number of their night-time awakenings.64 Actigraphy provides a non-invasive objective measure of sleep per week parameters in the child’s home environment. Nevertheless, sleep diaries remain an accessible and inexpensive way of assessing sleep in the clinical setting.

On occasion, it may be appropriate to use more advanced technology, such as a polysomnograph study. A polysomnograph is a laboratory-based test to diagnose and evaluate sleep disorders. It measures sleep, respiratory and other parameters (Table 30-2). It is not helpful in assessing insomnia because patients may sleep better than they normally do, or alternatively not sleep at all, due to the artificial environment of a sleep laboratory. It is particularly helpful for evaluating sleep-disordered breathing, or the assessment of upper airway obstruction and central sleep apnea. It also has a role in the pre-surgery assessment of patients at increased risk of anesthetic complications, such as spinal fusion for muscular dystrophy patients, and evaluation of patients after a brain tumor removal or spinal decompression. It can assist in the assessment of when to start non-invasive ventilatory support for at risk children, including those with neuromuscular conditions, and monitoring children receiving respiratory support during sleep such as supplemental oxygen, continuous positive airway pressure, and non-invasive ventilation.65 Collaboration and guidance from an experienced sleep pediatrician in relation to the appropriateness and use of these investigations is important.

| Category | Parameter and what it measures |

|---|

Management

The management of sleeping problems in children requires an interdisciplinary approach, not dissimilar to the management of chronic pain (Table 30-3). When symptoms are persistent and severe, there is a role for pharmacologic management. However, these must be used in conjunction with other nonpharmacologic strategies. This includes the management of psychologic distress, such as depression and anxiety, with input from a psychologist or psychiatrist. Because of the frequent coexistence and bidirectional effects of sleep disturbances and mood disorders, the most-effective treatment strategy generally involves an integrated approach that addresses both concerns simultaneously.

TABLE 30-3 Discipline-Specific Contributions to the Management of the Child with Insomnia

| Discipline | Discipline specific contributions | Overlapping contributions |

|---|---|---|

| Medical |

The approach to healthy children with sleeping problems has been either to avoid the use of medications or use medications only for a short duration.66 This is due to concerns over addiction to medications and lack of evidence for their long-term effectiveness in clinical studies. There is more evidence for developing nonpharmacologic strategies to manage sleep problems and many parents would also prefer this. Nonpharmacologic interventions may also be appealing for patients who are already taking a number of medications, such as in oncology.28,67

Provision of supplemental oxygen at night to patients with severe lung disease, such as CF and neuromuscular conditions, can improve daytime function and quality of life.68,69 The use of other respiratory support therapies should be evaluated in reference to the value in maintaining or improving quality of life. Children may benefit from non-invasive ventilation (NIV) during sleep for symptom management. NIV is readily available in most pediatric teaching hospitals and is increasingly available in the home and hospice settings. NIV can be seen as a treatment alternative to enotracheal ventilation for patients with end-stage terminal illness with a respiratory deterioration and in whom intensive care is electively declined or deemed inappropriate.69

The use of NIV in the pediatric palliative setting is limited by lack of experience, cost, access because therapy was being previously restricted to teaching hospitals, and lack of published trials to assess its efficacy.69 Symptoms related to upper airway obstruction, dyspnea associated with severe restrictive lung disease and problems of clearing secretion in children with suppurative lung disease and neuromuscular conditions might warrant consideration of a trial of NIV. Pediatric data are limited to case reports and small series of patients with neuromuscular conditions such as spinal muscular atrophy, particularly type II and III, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and children with brain tumors.25,70

Pharmacologic Management

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the National Sleep Foundation in America recognize that there are inadequate data to guide pharmacologic treatment of insomnia in children. There is no sleep medication for children that is approved by the Food and Drug Administration.66,67 There is an absence of safety and efficacy data for the use of benzodiazepines or newer non-benzodiazapine hypnotics for children with insomnia. This chapter summarizes the authors’ opinions regarding the pharmacologic management of sleeping problems in the pediatric palliative care context and acknowledges the need for more research in this area (Table 30-4). Surveys of hospital patients have shown that just 3% of patients are prescribed medications for sleep, with antihistamines being commonly prescribed at 37% followed by benzodiazapines at 19%.71 One randomized controlled trial found that antihistamines were no more effective than placebo.72 Other research has suggested that sedating antihistamines should be used only as a short-term adjunct to a behavioral therapy program in healthy children and are unlikely to be of benefit to children with severe neurologic dysfunction.73,74

TABLE 30-4 Summary of Various Medications That Can Promote Sleep in Children

| Medication | Indications and notes |

|---|---|

| Analgesia (including opioids) |

Sleep disruption caused by dysfunction of the central nervous system will often require a trial of medication. Benzodiazapines target the GABA receptor and have been shown to increase total sleep duration. However, a recent meta-analysis of 45 randomized controlled trials have documented daytime drowsiness and other adverse effects in adults.75 Agents that have short half-lives, such as temazepam and oxazepam, may be advantageous in minimizing residual daytime drowsiness. Common adverse effects from over-sedation are respiratory depression and the rapid development of tolerance, which limits their usefulness. The newer non- benzodiazapine hypnotics including zolpidem or zopiclone, have the advantage of a short half-life and are therefore useful in the treatment of sleep onset insomnia while causing minimal morning hangover. These medications have less effect on sleep architecture and do not have the insomnia rebound effect experienced when benzodiazepine hypnotics are stopped abruptly. However, there is lack of experience or research in the effectiveness, dosing, and side effects of these medications in pediatrics.41,76

At times, nocturnal irritability may be so severe that sedation is required to provide comfort to the child and rest to the caretakers. Clonidine and chloral hydrate are described in the literature as being particularly effective for children with cerebral irritability.17 Factors such as the child’s overall level of function, both baseline and sleep loss–related, the degree of nighttime disturbance, and the desires of the parents or other caretakers should be carefully considered.17 If used, one should be sure that daytime function is improved, that the lowest effective dose is chosen, and that periodic drug withdrawals are trialed to ensure the drug’s continued necessity.60

Endogenous melatonin is a hormone produced by the pineal gland at night and also plays a major role in the synchronization of circadian rhythms. There are a number of randomized controlled studies on the use of melatonin in children published in the literature, but more research is required.77 These studies are generally small in number and vary in the dosage of melatonin given from 0.3-10 mg. Melatonin usage appears safe in the short term with minimal side effects; however, there are concerns that melatonin can lower the seizure threshold. There has been one randomized, placebo-controlled trial of controlled release melatonin in children with neuro- developmental disability showing benefit in terms of sleep latency, clinician and patient rated variables, sleep efficiency and reduced family stress.78 In a survey of children with Sanfilippo syndrome, parents found melatonin used in conjunction with benzodiazepines was the most effective pharmacologic treatments of sleeping difficulties.23

Some medications, such as diuretics and steroids, which the child is on may also be contributing to sleep disturbance and these should be reviewed.19 Switching drugs, dosage regimens, or routes of administration may assist sleep. A combination of medications, each at lower doses, from two or three classes is sometimes more effective and preferred over increasing the dose of a single agent. Opioid analgesics can cause a delirium, and sometimes vivid dreams, and, in this context, a switch to an alternative opioid may be appropriate.79 Lamotrigine is an anti-seizure medication that can cause irritability and sleep disturbance. Consideration of switching to another anti-epileptic that also sedates, such as clobazam or phenobarbitone, could be considered.

Nonpharmacologic Management

Providing children and parents with nonpharmacologic methods of sleep management can assist children to sleep and empower the family. Simple measures may go a long way to increasing restful sleep for the whole family. This includes both environmental modifications and behavioral therapies.23 Behavioral approaches can be rapidly successful for treating sleep problems, even where the sleep problems are long-standing, severe and associated with physical, psychologic, or intellectual problems.80

Feedback from children and parents shows a number of small practical steps that can be undertaken to improve children’s sleep when they are hospitalized.32 Examples include avoiding oral medications at times when children would be expected to be asleep, turning off monitor alarms as soon as possible and keeping other night time interventions to a minimum. Ward routines that are flexible in allowing children to fulfill their own sleep requirements are important to consider, including allowing children to go to sleep at a similar time as they would at home, and use of activities such as bedtime reading or having a glass of milk or small snack just before bedtime.

Sleep hygiene relates to creating a sleep-friendly bedtime routine. It can be challenging to implement such a routine when children have a medical illness or neuro-developmental disability.81 The hour before bedtime should be a quiet time for shared pleasures, with television, computer games, and other stimulating activities restricted. A cool, quiet, comfortable bedroom will also promote sleep. Special overlays may be used to manage temperature-regulation difficulties. A variety of specialized positioning equipment can be used to provide postural support during sleep, for management of deformity, comfort, breathing, digestion, and safety. Specialized beds, mattresses and pillows can also be beneficial. Children are also often comforted by a dim nightlight, and a familiar transitional object such as a stuffed animal.

Thirty minutes of bright light exposure in the early morning will lead to better modulation of melatonin in the child’s body between daytime and nighttime. This also improves daytime functioning. Restful sleep is promoted by trying to aim for a regular waking time, both on school days and weekends. Where possible it is helpful to keep a child busy and active during the day, and limit naps to mid-afternoon. Children that are forced by illness or incapacitation to spend long amounts of time in bed run greater risk of associating their bed with wakefulness rather than sleep, which can further compound sleep difficulties. Thus, even very sick children might benefit from having different places to spend during the day. There is some evidence that daytime activities, such as a short time of exercise, will enhance sleep at night in children undergoing chemotherapy.28 Ongoing involvement at school, visits by friends, or the use of expressive therapies, such as play and music, can also help to keep children occupied during the day.

While it can be difficult for parents to set firm limits around a bedtime routine in the palliative care context, sometimes this is required to allow both the child and family to have adequate sleep and maintain quality of life during the day.60 Some balance needs to be maintained when negotiating this with children and families, because some parents may be happy to stay up late at night with their child if that is the time that they are most interactive with their family. Such interaction is only sustainable for a short period of time and may not be appropriate to facilitate if the child is not at an end-of-life phase of their illness. Some children during the end stages of their disease, and for various reasons, will develop a delayed sleep phase of going to bed later and waking late in the morning. Some parents are happy to accommodate this change in sleeping pattern and acknowledgement of this is all that may be required.

Commonly used intervention techniques in adults include training in relaxation strategies and mind meditation techniques.30 A recent study of adult patients with persistent insomnia, showed the addition of medication, Zolpidem, to cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) produced added benefits during acute therapy, but long-term outcome was optimized when medication was discontinued during maintenance CBT.82 A recent study demonstrated that trained and supervised nurses can effectively deliver cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in general practice.83 This included education about sleep hygiene and establishing a bedtime routine.

Research into the effectiveness of CBT has also focused on children with anxiety and insomnia.84 CBT focuses on helping children to learn the connections among thoughts, feelings and behaviors, and learn specific skills to begin to think, feel, and behave in more positive and helpful ways. There is also a role for resources that provide children psycho-education and give them autonomy in managing their sleep problems, such as books and group work.60,85 An integrated approach is beneficial in that cognitive restructuring strategies can be highly effective for both sleep disturbance and psychiatric issues.54 Cognitive restructuring involves an active process of challenging negative, unhelpful or unrealistic thoughts and generating more accurate or helpful interpretations of situations in order to facilitate coping. Aside from changes to bedtime routines and behavior, behavioral components of CBT can involve gradual exposure to situations that are feared or avoided. Facing feared situations provides opportunities to test fearful predictions, while also providing self-mastery experiences and an opportunity for children to develop coping skills. More significant and chronic fears cannot be dealt with by such behavioral methods alone and counseling must be considered. It is important that both children and parents are given close follow-up and support.60

Co-sleeping or bed sharing is another strategy that parents adopt to assist their children to sleep. In some studies, bed sharing of at least once per week was noted in 44% of the children between age 2 and 7 years old.86 There are also significant cultural variations in this practice. In cultures where children share their parents’ bed, night waking is not such a problem.60 An increased prevalence of bed and room sharing has been found amongst Asian, African American, and indigenous children.87–90 Factors associated with this practice in China included younger age, large family, children without their own bedrooms, and parents’ approval of a co-sleeping arrangement.87 Swedish children also often co-sleep with both their parents until school age, when more boys than girls cease the practice. Co-sleeping in Sweden is perceived as a normal family activity, which differs from other Western cultures.91

Children during an illness, particularly if it is terminal, may seek reassurance from parents at night, particularly when they are fearful. Other approaches should be considered if the child is not receiving end-of-life care and is expected to live more than one month. Having the child continue to sleep in his or her own bedroom with the parent available, although not sleeping in the same bed, is a more sustainable compromise. Parents also demonstrating love, care, and their ability to provide safety and protection to their child will also be important in this context (Fig. 30-6).

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Treatments

Given the preponderance of patients who may be employing complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) treatments and techniques for insomnia, it is important that clinicians be familiar with these approaches.92 Research into pharmacologic complementary and alternative substances to treat sleep disturbances in patients, both adult and pediatric, is almost nonexistent. There is insufficient evidence to recommend valerian for insomnia.5 There is also interest in the effectiveness of traditional Chinese medicine, massage, and acupuncture in managing sleeping problems in adults.93,94 Another study that explored the effectiveness of hypnosis treatment in children experiencing loss, such as the death of a parent or sibling, showed promise by concluding that young children can be taught self-hypnosis to manage their sleeping problems effectively.95

linical Vignettes

Amy, 8, had a primary diagnosis of relapsed rhabdomyosacroma involving her lungs and sacrum (Fig. 30-7). She developed back and abdominal pain on the fourth day of a bone marrow transplant. Patient-controlled analgesia using fentanyl was commenced to manage her pain. Subsequently to this, she developed bright and vivid dreams, which were distressing. These dreams were characteristic of the dreams associated with opioid analgesia. Her analgesia was changed to hydromorphone and her dreams settled. She also had diazepam to assist with sleep initiation for three nights at this time.

There was no pattern to his sleep disturbance. He had minimal sleep during the day.

1 Hippocrates, Aphorism LXXI in Sateia MJ, Nowell PD. Insomnia. Lancet. 2004;364(9449):1959-1973.

2 Splaingard M. Sleep medicine. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51:xiii-xiv.

3 Blask D.E. Melatonin, sleep disturbance and cancer risk. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13(4):257-264.

4 Rosen G.M. Sleep in children who have cancer. Sleep Med Clin. 2007;2:491-500.

5 Bartlett D.J., Paisley L., Desai A.V. Insomnia diagnosis and management. Medicine Today. 2006;7(8):14-21.

6 American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Revised—Diagnostic and Coding Manual. Westchester: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2001.

7 American Psychiatric Association. Revised ed 4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 2000. American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC.

8 Rosen G. Evaluation of the patient who has sleep complaints: a case-based method using the sleep matrix process. Prim Care Clin Office Pract. 2005;32:319-328.

9 Lee K.A. Continuing education program integrating and understanding of sleep knowledge into your practice. Am Nurse. 1995:26-27.

10 Iglowstein I., Jenni O.G., Molinari L., et al. Sleep duration from infancy to adolescence: Reference values and generational trends. Pediatrics. 2003;111:302-307.

11 Yang C., Kim J.K., Patel S.R., et al. Age-related changes in sleep/wake patterns among Korean teenagers. Pediatrics. 2005;115:250-256.

12 Dollman J., Ridley K., Olds T., et al. Trends in the duration of school-day sleep among 10- to 15-year-old South Australians between 1985 and 2004. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96(7):1011-1014.

13 Richman N. Sleep problems in young children. Arch Dis Child. 1981;56(7):491-493.

14 Klackenberg G. Sleep behaviour studied longitudinally. Data from 4-16 years on duration, night-awakening and bed-sharing. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1982;71(3):501-506.

15 Dahl R.E., Carskadon M.A. Sleep and its disorders in adolescence. In: Ferber R., Kryger M.H., editors. Principles and practice of sleep medicine in the child. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1995:19-27.

16 Smaldone A., Honig J.C., Byrne M.W. Sleepless in America: inadequate sleep and relationships to health and well-being of our nation’s children. Pediatrics. 2007;119(Suppl 1):S29-S37.

17 Ferber R. Childhood sleep disorders. Neurol Clin. 1996;14(3):493-511.

18 Naqvi S.K., Sotelo C., Murry L., et al. Sleep architecture in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis and the association with severity of lung disease. Sleep Breath. 2008;12(1):77-83.

19 Bandla H., Splaingard M. Sleep problems in children with common medical disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51:203-227.

20 Stenekes S.J., Hughes A., Grégoire M.C., et al. Frequency and self-management of pain, dyspnea and cough in cystic fibrosis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(6):837-848.

21 Walz N.C., Beebe D., Byars K. Sleep in individuals with Angelman syndrome: parent perceptions of patterns and problems. Am J Ment Retard. 2005;110(4):243-252.

22 Young D., Nagarajan L., de Klerk N., et al. Sleep problems in Rett syndrome. Brain Dev. 2007;29(10):609-616.

23 Fraser J., Gason A.A., Wraith J.E., et al. Sleep disturbance in Sanfilippo syndrome: a parental questionnaire study. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(12):1239-1242.

24 Zucconi M., Bruni O. Sleep disorders in children with neurologic diseases. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2001;8(4):258-275.

25 Rosen G.M., Bendel A.E., Neglia J.P., et al. Sleep in children with neoplasms of the central nervous system: case review of 14 children. Pediatrics. 2003;112(1 Pt 1):e46-e54.

26 Collins J.J., Byrnes M.E., Dunkel I.J., et al. The measurement of symptoms in children with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(5):363-377.

27 Collins J.J., Devine T.D., Dick G.S., et al. The measurement of symptoms in young children with cancer: the validation of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale in children aged 7-12. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23(1):10-16.

28 Hinds P.S., Hockenberry M., Rai S.N., et al. Clinical field testing of an enhanced-activity intervention in hospitalized children with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(6):686-697.

29 Miser A., McCalla J., Dothage J. Pain as a presenting symptom in children and young adults with newly diagnosed malignancy. Pain. 1987;29:85-90.

30 Berger A.M., Parker K.P., Young-McCaughan S., et al. Sleep wake disturbances in people with cancer and their caregivers: state of the science. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32(6):E98-E126.

31 Chalkiadis G.A. Management of chronic pain in children. MJA. 2001;175:476-479.

32 Herbert A., De Lima J., Seton C., et al. A survey of sleeping patterns in children admitted to hospital. Sleep and Biological Rhythms. 2008;6(Suppl 1):A49.

33 Lewin D.S., Dahl R.E. Importance of sleep in the management of pediatric pain. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1999;20(4):244-252.

34 Gedaly-Duff V., Lee K.A., Nail L., et al. Pain, sleep disturbance, and fatigue in children with leukemia and their parents: a pilot study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33(3):641-646.

35 Rose M., Sanford A., Thomas C., et al. Factors altering the sleep of burned children. Sleep. 2001;24(1):45-51.

36 Raymond I., Nielsen T.A., Lavigne G., et al. Quality of sleep and its daily relationship to pain intensity in hospitalized adult burn patients. Pain. 2001;92(3):381-388.

37 Roehrs T., Hyde M., Blaisdell M.S., et al. Sleep loss and REM sleep are hyperalgesic. Sleep. 2006;29(2):145-151.

38 Theunissen P.MH. Symptoms in the palliative phase of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49(2):160-165.

39 Drake R., Frost J., Collins J.J. The symptoms of dying children. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26(1):594-603.

40 Wolfe J., Grier H.E., Klar N., et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):326-333.

41 Pelayo R., Chen W., Monzon S., et al. Pediatric sleep pharmacology: you want to give my kid sleeping pills? Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51:117-134.

42 Vella-Brincat J., Macleod A.D. Adverse effects of opioids on the central nervous system of palliative care patients. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21(1):15-25.

43 Hagemann V. Night sleep of children in a hospital. Part I: sleep duration. Matern Child Nurs J. 1981;10(1):1-13.

44 Hagemann V. Night sleep of children in a hospital. Part II: sleep disruption. Matern Child Nurs J. 1981;10(2):127-142.

45 Corser N.C. Sleep of 1- and 2-year-old children in intensive care. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 1996;19(1):17-31.

46 Naughton F., Ashworth P., Skevington S.M. Does sleep quality predict pain-related disability in chronic pain patients? The mediating roles of depression and pain severity. Pain. 2007;127(3):243-252.

47 Widger K., Davies D., Drouin D.J., et al. Pediatric patients receiving palliative care in Canada: results of a multicenter review. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(6):597-602.

48 Sadeh A., Raviv A., Gruber R. Sleep patterns and sleep disruptions in school-age children. Dev Psychol. 2000;36(3):291-301.

49 Dinges D.F., Pack F., Williams K., et al. Cumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4-5 hours per night. Sleep. 1997;20:267-277.

50 Alfano C.A., Beidel D.C., Turner S.M., et al. Preliminary evidence for sleep complaints among children referred for anxiety. Sleep Med. 2006;7:467-473.

51 Hudson J.L., Gradisar M., Gamble A., et al. The sleep patterns and problems of clinically anxious children. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:339-344.

52 Forbes E.E., Bertocci M.A., Gregory A.M., et al. Objective sleep in pediatric anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder. J Am Acad Child Psy. 2008;47:148-155.

53 Forbes E.E., Williamson D.E., Ryan N.D., et al. Peri-sleep-onset cortisol levels in children and adolescents with affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59(1):24-30.

54 Hudson J.L., Rapee R.M. Parental perceptions of overprotection: Specific to anxious children or shared between siblings? Behav Change. 2005;22(3):185-194.

55 van der Bruggen C.O., Stams G.J., Bögels S.M. Research Review: the relation between child and parent anxiety and parental control: a meta-analytic review. J Child Psychol Psyc. 2008;49(12):1257-1269.

56 Adair R., Bauchner H., Philipp B., et al. Night waking during infancy: role of parental presence at bedtime. Pediatrics. 1991;87:500-504.

57 Meltzer L.J., Mindell J.A. Nonparmacologic treatments for pediatric sleeplessness. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51:135-151.

58 Benca R.M., Obermeyer W.H., Thisted R.A., et al. Sleep and psychiatric disorders. A meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49(8):651-668.

59 Liu X., Buysse D.J., Gentzler A.L., et al. Insomnia and hypersomnia associated with depressive phenomenology and comorbidity in childhood depression. Sleep. 2007;30(1):83-90.

60 Ferber R. The Sleepless Child. In: Guilleminault C., editor. Sleep and its disorders in children. New York: Raven Press; 1987:141-163.

61 Cross S.J. Assessment of sleep in hospital patients: a review of methods. J Adv Nurs. 1988;13:501-510.

62 Owens J.A., Dalzell V. Use of the “BEARS” sleep screening tool in a pediatric residents’ continuity clinic: a pilot study. Sleep Med. 2005;6(1):63-69.

63 Owens J.A. Epidemiology of sleep disorders during childhood. In: Sheldon S.A., editor. Principles and practice of pediatric sleep medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2005:27-33.

64 Sadeh A. Evaluating night wakings in sleep-disturbed infants: a methodological study of parental reports and actigraphy. Sleep. 1996;19(10):757-762.

65 Waters K. Interventions in the paediatric sleep laboratory: The use and titration of respiratory support therapies. Paed Resp Rev. 2008;9:181-192.

66 Stojanovski S.D., Rasu R.S., Balkrishnan R., et al. Trends in medication prescribing for pediatric sleep difficulties in US outpatient settings. Sleep. 2007;30(8):1013-1017.

67 Mindell J.A., Emslie G., Blumer J., et al. Pharmacologic management of insomnia in children and adolescents: consensus statement. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):e1223-e1232.

68 Zinman R., Corey M., Coates A.L., et al. Nocturnal home oxygen in the treatment of hypoxemic cystic fibrosis patients. J Pediatr. 1989;114:368-377.

69 Collins J.J., Fitzgerald D.A. Palliative care and paediatric respiratory medicine. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2006;7:281-287.

70 Simonds A.K. Nocturnal ventilation in neuromuscular disease: when and how? Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2002;57:373-376.

71 Meltzer L.J., Mindell J.A., Owens J.A., et al. Use of sleep medications in hospitalized pediatric patients. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6):1047-1055.

72 Merenstein D., Diener-West M., Halbower A.C., et al. The trial of infant response to diphenhydramine: the TIRED study: a randomized, controlled, patient-oriented trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(7):707-712.

73 France K.G., Blampied N.M., Wilkinson P. Treatment of infant sleep disturbance by trimeprazine in combination with extinction. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1991;12(5):308-314.

74 France K.G., Blampied N.M., Wilkinson P. A multiple-baseline, double-blind evaluation of the effects of trimeprazine tartrate on infant sleep disturbance. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;7(4):502-513.

75 Holbrook A.M., Crowther R., Lotter A., et al. Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of insomnia. CMAJ. 2000;162:225-233.

76 Herman J.H., Sheldon S.H. Pharmacology of sleep disorders in children. In: Sheldon S.H., Ferber R., Kryger M.H., editors. Principles and practice of pediatric sleep medicine. Saunders; 2005:327-328.

77 Smits M.G., van Stel H.F., van der Heijden K., et al. Melatonin improves health status and sleep in children with idiopathic chronic sleep-onset insomnia: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(11):1286-1293.

78 Wasdell M.B., Jan J.E., Bomben M.M., et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of controlled release melatoning of delayed sleep phase syndrome and impaired sleep maintenance in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities. J Pineal Res. 2008;44:57-64.

79 Drake R., Longworth J., Collins J.J. Opioid rotation in children with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(3):419-422.

80 Wiggs K., France L. Behavioural treatments for sleep problems in children and adolescents with physical illness, psychological problems or intellectual disabilities. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4(3):299-314.

81 Jan J.E., Owens J.A., Weiss M.D. Sleep hygiene for children with neurodevelopmental disabilities. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6):1343-1350.

82 Morin C.M., Vallières A., Guay B., et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy, singly and combined with medication, for persistent insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(19):2005-2015.

83 Espie C.A., MacMahon K.M., Kelly H.L., et al. Randomized clinical effectiveness trial of nurse-administered small-group cognitive behavior therapy for persistent insomnia in general practice. Sleep. 2007;30(5):574-584.

84 Bélanger L., Morina C.M., Langloisa F., et al. Insomnia and generalized anxiety disorder: effects of cognitive behavior therapy for GAD on insomnia symptoms. J Anxiety Disord. 2004;18(4):561-571.

85 Culbert T., Kajander R. Be the boss of your sleep. Minneapolis: Free Spirit Publishing, 2007.

86 Jenni O.G., Fuhrer H.Z., Iglowstein I., et al. A longitudinal study of bed sharing and sleep problems among Swiss children in the first ten years of life. Pediatrics. 2005;115(Suppl 1):233-2240.

87 Li S., Jin X., Yan C., Wu S., Jiang F., Shen X. Factors associated with bed and room sharing in Chinese school-aged children. Child Care Health Dev. 2009;35(2):171-177.

88 Chng S.Y. Sleep disorders in children: the Singapore perspective. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37(8):706-709.

89 Javo C., Rønning J.A., Heyerdahl S. Child-rearing in an indigenous Sami population in Norway: a cross-cultural comparison of parental attitudes and expectations. Scand J Psychol. 2004;45(1):67-78.

90 Lozoff B., Wolf A.W., Davis N.S. Co-sleeping in urban families with young children in the United States. Pediatrics. 1984;74:171-182.

91 Welles-Nystrom B. Co-sleeping as a window into Swedish culture: considerations of gender and health care. Scand J Caring Sci. 2005;19(4):354-360.

92 Kierlin L. Sleeping without a pill: nonpharmacologic treatments for insomnia. J Psychiatr Pract. 2008;14(6):403-407.

93 Zhou Y., Wei Y., Zhang P., et al. The short-term therapeutic effect of the three-part massotherapy for insomnia due to deficiency of both the heart and the spleen: a report of 100 cases. J Tradit Chin Med. 2007;27(4):261-264.

94 Zhong Z.G., Cai H., Li X.L., et al. Effect of acupuncture combined with massage of sole on sleeping quality of the patient with insomnia. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu. 2008;28(6):411-413. [Article in Chinese.]

95 Hawkins P., Polemikos N. Hypnosis treatment of sleeping problems in children experiencing loss. Contemporary Hypnosis. 2002;19(1):18-24.