Chapter 9 Skull

The skull is the bony skeleton of the head and is the most complex osseous structure in the body. It is protective, shielding the brain, the organs of special sense and the cranial parts of the respiratory and digestive systems. It also provides attachments for many of the muscles of the head and neck, thus allowing for movement. Of particular importance is movement of the lower jaw (mandible), which occurs at the temporomandibular joint. The marrow within the skull bones is a site of haemopoiesis, at least in the young skull.

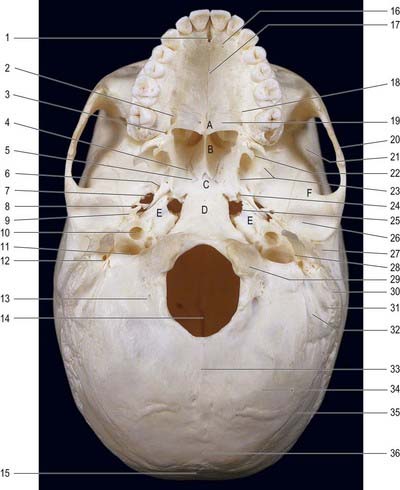

Inferior (Basal) Surface

The inferior surface of the skull, the base of the cranium, is complex and extends from the upper incisor teeth in front to the superior nuchal lines of the occipital bone behind (Fig. 9.1). The region contains many of the foramina through which structures enter and exit the cranial cavity. The inferior surface can be conveniently divided into anterior, middle, posterior and lateral parts. The anterior part contains the hard palate and the dentition of the upper jaw, and it lies at a lower level than the rest of the cranial base. The middle and posterior parts can be arbitrarily divided by a transverse plane passing through the anterior margin of the foramen magnum. The middle part is occupied mainly by the base of the sphenoid bone, the petrous processes of the temporal bones and the basilar part of the occipital bone. The lateral part contains the zygomatic arches and the mastoid and styloid processes. Whereas the middle and posterior parts are directly related to the cranial cavity (the middle and posterior cranial fossae), the anterior part (the palate) is some distance from the anterior cranial fossa, being separated from it by the nasal cavities.

Fig. 9.1 Inferior view of the skull.

(By permission from Berkovitz, B.K.B., Moxham, B.J., 1994. Color Atlas of the Skull. Mosby-Wolfe, London.)

Anterior Part of the Cranial Base

The nasal fossae, separated in the midline by the nasal septum, lie above the hard palate. The two posterior nasal apertures (choanae) are located where the nasal fossae end. The posterior part of the septum is formed by the vomer. The upper border of the vomer is applied to the inferior aspect of the body of the sphenoid, where it expands into an ala on each side. The lateral border of each ala reaches a thin vaginal process that projects medially from the medial pterygoid plate. The two may touch, or the vaginal process may overlap the ala of the vomer inferiorly. The inferior surface of the vaginal process bears an anteroposterior groove, which is converted into a canal anteriorly by the superior aspect of the sphenoidal process of the palatine bone. This palatovaginal canal opens anteriorly into the pterygopalatine fossa and transmits a pharyngeal branch of the pterygopalatine ganglion and a pharyngeal branch from the third part of the maxillary artery. An inconstant vomerovaginal canal may lie between the ala of the vomer and the vaginal process of the sphenoid bone, medial to the palatovaginal canal, and lead into the anterior end of the palatovaginal canal. It transmits the pharyngeal branch of the third part of the maxillary artery.

Middle Part of the Cranial Base

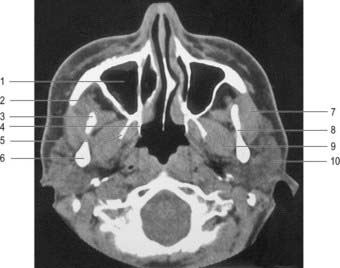

Each pterygoid process of the sphenoid bone bears medial and lateral pterygoid plates separated by a pterygoid fossa. Anteriorly, the plates are fused, except below, where they are separated by the pyramidal process of the palatine bone. Sutures are usually discernible at this site. Laterally, the pterygoid plates are separated from the posterior maxillary surface by the pterygomaxillary fissure, which leads into the pterygopalatine fossa. The posterior border of the medial pterygoid plate is sharp and bears a small projection near the midpoint, above which it is curved and attached to the pharyngeal end of the pharyngotympanic tube. Above, the medial pterygoid plate divides to enclose the scaphoid fossa; below, it projects as a slender pterygoid hamulus, which curves laterally and is grooved anteriorly by the tendon of tensor veli palatini. The pterygoid hamulus gives origin to the pterygomandibular raphe. The lateral pterygoid plate projects posterolaterally, and its lateral surface forms the medial wall of the infratemporal fossa. Superiorly and laterally, the pterygoid process is continuous with the infratemporal surface of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone, which forms part of the roof of the infratemporal fossa. This surface forms the posterolateral border of the inferior orbital fissure and bears an infratemporal crest associated with the origin of the upper part of the lateral pterygoid. The infraorbital and zygomatic branches of the maxillary nerve and accompanying vessels pass through the inferior orbital fissure. Laterally, the greater wing of the sphenoid bone articulates with the squamous part of the temporal bone. Features associated with the pterygoid plate region can be assessed radiographically (Fig. 9.2).

The foramen ovale and foramen spinosum lie lateral to the foramen lacerum on the infratemporal surface of the greater wing of the sphenoid bone. The foramen ovale, near the posterior margin of the lateral pterygoid plate, transmits the mandibular nerve as well as the lesser petrosal nerve, the accessory meningeal branch of the maxillary artery and an emissary vein that connects the cavernous venous sinus to the pterygoid venous plexus in the infratemporal fossa. Posterolaterally, the smaller and rounder foramen spinosum transmits the middle meningeal artery and a meningeal branch of the mandibular nerve. The irregular spine of the sphenoid projects posterolateral to the foramen spinosum. The medial surface of the spine is flat and forms, with the adjoining posterior border of the greater wing of the sphenoid, the anterolateral wall of a groove that is completed posteromedially by the petrous part of the temporal bone. This groove contains the cartilaginous pharyngotympanic (auditory) tube and leads posterolaterally into the bony portion of the tube lying within the petrous part of the temporal bone. Occasionally, the foramen ovale and foramen spinosum are confluent. The posterior edge of the foramen spinosum may be defective. A small foramen, the sphenoidal emissary foramen (of Vesalius), is sometimes found between the foramen ovale and scaphoid fossa. When present, it contains an emissary vein linking the pterygoid venous plexus in the infratemporal fossa with the cavernous sinus in the middle cranial fossa.

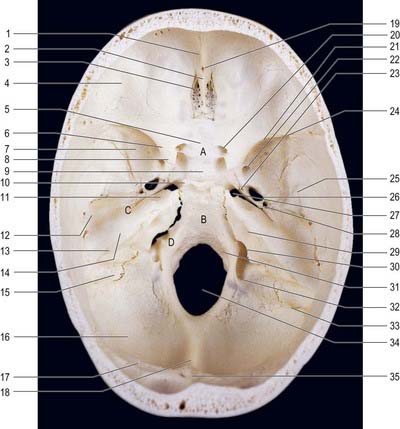

Cranial Fossae

The base of the cranial cavity is divided into three distinct fossae: anterior, middle and posterior (Fig. 9.3). The floor of the anterior cranial fossa is at the highest level and the floor of the posterior fossa is at the lowest.

Fig. 9.3 Floor of the cranial cavity showing the cranial fossae.

(By permission from Berkovitz, B.K.B., Moxham, B.J., 1994. Color Atlas of the Skull. Mosby-Wolfe, London.)

Anterior Cranial Fossa

The convex cranial surface of the frontal bone separates the brain from the orbit and bears impressions of cerebral gyri and small grooves for meningeal vessels. Posteriorly, it joins the anterior border of the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone, which forms the posterior boundary of the anterior cranial fossa. The medial end of the lesser wing constitutes the anterior clinoid process. The lesser wing joins the body of the sphenoid body by two roots that are separated by the optic canal. The anterior root, broad and flat, is continuous with the jugum sphenoidale; the smaller and thicker posterior root joins the body of the sphenoid bone near the posterior bank of the sulcus chiasmatis. The frontosphenoid and sphenoethmoidal sutures divide the sphenoid from the adjacent bones.

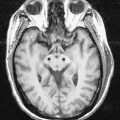

CASE 1 Foster Kennedy Syndrome

Discussion: Owing to the subfrontal site of this woman’s tumour, she developed anosmia due to primary involvement of the olfactory nerve in the olfactory groove by the tumour, along with mild frontal signs such as behavioural change. Reduced visual acuity with optic atrophy is due to direct compression of the ipsilateral optic nerve or optic chiasma, whereas papilloedema involving the contralateral optic nerve clearly indicates the presence of increased intracranial pressure, a combination that is uncommon today in light of early diagnostic studies. See Figure 9.4.

Middle Cranial Fossa

A shallow trigeminal impression, adapted to the trigeminal ganglion, is situated posterior to the foramen lacerum on the anterior surface of the petrous part of the temporal bone, near its apex. Posterolateral to this impression is a shallow pit, limited posteriorly by a rounded arcuate eminence produced by the anterior semicircular canal. Lateral to the trigeminal impression, a narrow groove passes posterolaterally into the hiatus for the greater petrosal nerve, and even farther laterally is the hiatus for the lesser petrosal nerve. The anterior surface of the petrous part of the temporal bone is formed by the tegmen tympani, a thin osseous lamina in the roof of the tympanic cavity, which extends anteromedially above the auditory tube, anterolateral to the arcuate eminence. The posterior part of the tegmen tympani roofs the mastoid antrum, lateral to the eminence. The superior border of the petrous part of the temporal bone separates the middle and posterior cranial fossae and is grooved by the superior petrosal sinus. In young skulls, a petrosquamous suture may be visible at the lateral limit of the tegmen tympani, but it is obliterated in adults. The tegmen tympani then turns down as the lateral wall of the osseous auditory tube, and its lower border may appear in the squamotympanic fissure. Lateral to the anterior part of the tegmen tympani, the squamous part of the temporal bone is thin over a small area that coincides with the deepest part of the mandibular fossa.

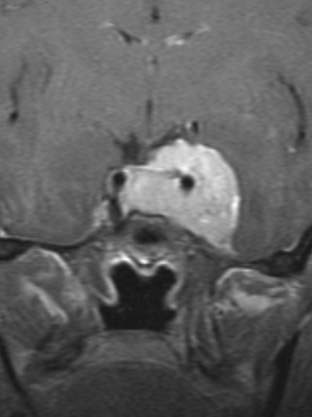

CASE 2 Pituitary Tumour with Bitemporal Visual Field Defect

Discussion: Bitemporal hemianopsia localizes the lesion to the optic chiasma, with involvement primarily of the decussating fibres originating in the nasal portion of the retina. Tumours in this area can compress both the optic nerves and optic chiasma, sometimes producing a mixed defect consisting of bitemporal visual field disturbances (as in this woman) and a superimposed monocular visual field disturbance—a so-called junctional defect. Such a combination of monocular and bitemporal visual field defects can be diagnostically challenging. See lesion 3, Figure 12.11. As this case demonstrates, patients with bitemporal visual field defects may be unaware of the vision loss.

Berkovitz B.K.B., Moxham B.J. Color Atlas of the Skull. London: Mosby-Wolfe; 1994.

Howells W.W. Cranial Variation in Man. vol. 67. 1973. Papers of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography. Cambridge, MA.

Lieberman D.E., McCarthy R.C. The ontogeny of cranial base angulation in humans and chimpanzees and its implications for reconstructing pharyngeal dimensions. J. Hum. E.. 1999;36:487-517.

Lieberman D.E., Pearson O.M., Mowbray K.M. Basicranial influence on overall cranial shape. J. Hum. E.. 2000;38(2):291-315.

Moos, Baker, 1998Moos K.F. Baker A.W. Craniofacial surgery: Assessment and techniques, Langdon J.D., Patel M.F. Operative Maxillofacial Surgery. 1998. Chapman & Hall. London. 407-436.

A detailed description of the various craniosynostoses.

Relethford J.H. Craniometric variation among modern human populations. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol.. 1994;95:53-62.