SKIN DISORDERS

SUNBURN

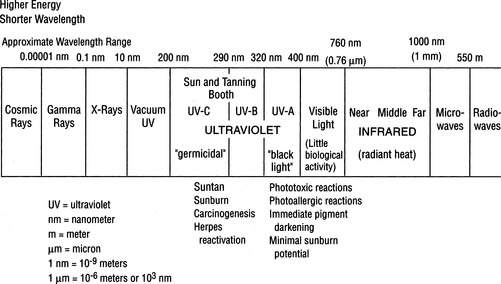

The solar radiation that strikes the earth includes 50% visible light (wavelength 400 to 760 nanometers [nm]), 40% infrared (760 to 1,700 nm), and 10% ultraviolet (UV) (10 to 400 nm) (Figure 119). Energetic rays (e.g., cosmic rays, gamma rays, and x-rays) with wavelengths shorter than 10 nm do not penetrate to the earth’s surface to any significant degree. Sunburn is a cutaneous photosensitivity reaction caused by exposure of the skin to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) from the sun. There are four types of UVR: vacuum UVR is 10 to 200 nm (absorbed by air and unable to penetrate Earth’s atmosphere), UVA is 320 to 400 nm, UVB is 290 to 320 nm, and UVC is 100 to 290 nm. UVC is filtered out by the ozone layer of the atmosphere. UVB is the culprit in the creation of sunburn and cancer. UVA is of less immediate danger but is a serious cause of skin aging, drug-related photosensitivity, and skin cancer. Furthermore, persons taking immunosuppressive agents for medical reasons (e.g., acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS] or cancer) may be more predisposed to skin cancer caused by UVA.

Wind appears to augment the injury, as do heat, atmospheric moisture, and immersion in water. “Windburn” is not possible without UVR or abrasive sand. Since windburn is due in part to the drying effect of low humidity at high altitudes, it can be helpful to protect the skin with a greasy sunscreen or barrier cream.

If the victim is deep red (“lobster”) without blisters, a stronger antiinflammatory drug, such as prednisone, may be given. A 5-day course of prednisone (80 mg on the first day, 60 mg the second, 40 mg the third, 20 mg the fourth, and 10 mg the fifth) may decrease the discomfort of “sun poisoning,” which is the constellation of low-grade fever, loss of appetite, nausea, and weakness that accompanies a bad total-body sunburn. Corticosteroids should always be taken with the understanding that a rare side effect is serious deterioration of the head (“ball” of the ball-and-socket joint) of the femur, the long bone of the thigh. An extensive nonblistering first-degree sunburn can make the victim nauseated and weak, with low-grade fever and chills. He should be forced to drink enough balanced electrolyte-supplemented liquids to avoid dehydration (see page 208).

With a severe sunburn in which blistering is present, the victim has by definition suffered second-degree burns (see page 108) and should be treated accordingly. Gently clean the burned areas and cover with sterile dressings. Administer appropriate pain medication.

SUNSCREENS

Type I. Always burns easily, never tans. (Fair-skinned people with a high number of moles are at the greatest risk for melanoma.)

Type II. Always burns easily, tans minimally.

Type III. Burns moderately, tans gradually and uniformly (light brown).

Type IV. Burns minimally, always tans well (moderate brown).

In all cases it is wise to overestimate the protection necessary and to carry a strong sunscreen. To protect hair from sun damage, wear a hat.

Substantivity refers to the ability of a sunscreen to resist water wash-off. Layering sunscreens doesn’t work well, because the last layer applied usually washes off. Current specialty sunscreens with high substantivity include Bullfrog Water Pro Body Gel, Aloe Gator Total Sun Block Lotion, and Dermatone Ultimate Fisherman’s Sunscreen.

Sunscreens are first applied to cool, dry skin for optimal absorption; wait 10 minutes before water exposure. Reapply them liberally after swimming or heavy perspiration. In general, most sunscreens should be reapplied every 20 minutes to 2 hours. Be aware that the concomitant use of insect repellent containing DEET (see page 390) lowers the effectiveness of the sunscreen by a factor of one-third. Although many sunscreens are designed to bond or adhere to the skin under adverse environmental conditions, there are certain situations in which any sunscreen should be reapplied at a maximum of 3- to 4-hour intervals:

• Continuous sun exposure, particularly between the hours of 10 a.m. and 3 p.m.

• Exposure at altitude of 7,000 ft (2,135 m) or higher

• Exposure within 20 degrees latitude of the equator

• Exposure during May through July in the Northern Hemisphere, and December through February in the Southern Hemisphere

• Frequent water immersion, particularly with toweling off

• Preexisting sunburn or skin irritation

• Ingestion of drugs, such as certain antibiotics, that can cause photosensitization

If you are concerned about jellyfish stings, a useful product is Safe Sea Sunblock with Jellyfish Sting Protective Lotion (www.buysafesea.com), which is both a sunscreen and a jellyfish sting inhibitor.

Although “tanning tablets” or “bronzers” induce a pigmentary change in the skin that resembles a suntan, they provide minimal, if any, true protection from the effects of ultraviolet exposure. Like the sun, indoor tanning machines induce skin changes that lead to premature skin aging and cancer. The best tan derived from the natural sun’s UVB carries an SPF of approximately 2; a tanning bed supplies UVA and therefore no protection.

MELANOMA

Warning signs within a skin lesion include the following:

1. Irregular, ragged, jagged, notched, or blurred border.

2. Asymmetrical appearance (one portion different from the rest, with respect to color, darkness, or texture).

3. Change in appearance or features (size, color, texture, sensation); onset of pain in a lesion; rapid growth of a lesion.

4. Recent growth, bleeding, itching, scaling, or tenderness.

5. Discoloration (black, dark brown, blue, red, white, mottled).

POISON IVY, SUMAC, AND OAK (GENUS TOXICODENDRON)

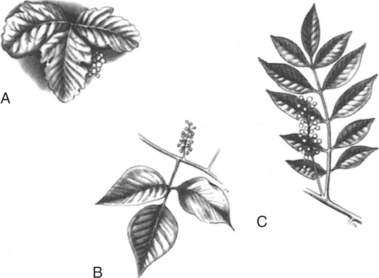

The rashes of poison ivy, poison sumac, and poison oak are caused by a resin (urushiol) found in the resin canals of leaves, stems, vines, berries, and roots (Figure 120). The resin is not found on the surface of the leaves. The potency of the sap does not vary with the seasons. In its natural state, the oil is colorless; on exposure to air, oxidation causes it to turn black. Because the plant parts have to be injured to leak the resin, most cases are reported in spring, when the leaves are most fragile. Dried leaves are less toxic, because the oil has returned to the stem and roots through the resin canals. However, smoke from burning plants carries the residual available resin in small particles and can cause a severe reaction on the skin and in the nose, mouth, throat, and lungs.

The poison oak group does not grow in Alaska or Hawaii, and it rarely grows above 4000 ft (1219 m). Other plants or parts of plants that contain urushiol include the India ink tree, mango rind, cashew nut shell, and Japanese lacquer tree. A smaller number of reactions are caused by the poisonwood tree found in the southern tip of Florida. Because the resin is long lived, it can be spread by contact with tents, clothing, and pet fur.

For treatment of the skin reaction, shake lotions such as calamine are soothing and drying, and they control itching. A good nonsensitizing topical anesthetic is pramoxine hydrochloride 1% (Prax cream or lotion); Caladryl contains calamine and pramoxine. Avoid topical diphenhydramine, benzocaine, and tetracaine. Antihistamines (such as diphenhydramine [Benadryl]) control itching and act as sedatives. Nonsedating antihistamines, such as fexofenadine (Allegra), may also diminish itching. A soothing bath in tepid (not hot) water with half a 1 lb box of baking soda, 2 cups (551 ml) of linnet starch, or 1 cup (275 mL) Aveeno oatmeal is excellent. If Aveeno is not available, a woman’s nylon stuffed with regular (not instant) oatmeal can be thrown in the tub. Soothing aluminum acetate in water (1:20) soaks may help, as might aluminum subacetate (Burow’s solution, Domeboro), which comes as a 5% solution that should be diluted to a 1:40 concentration. When these soaks are used, they should be applied as cotton-soaked wet dressings 3 to 4 times a day for 15 to 30 minutes per application to dry out the weeping rash. Topical steroid creams are generally of little value. Potent topical steroid ointments are not effective unless they are applied before the appearance of blisters and continued for 2 to 3 weeks, so are not recommended. Alcohol applications are painful and do not hasten resolution of the rash. There are new topical agents, such as pimecrolimus (Elidel) 1% cream and tacrolimus (Protopic) 0.03% or 0.1% ointment, which modulate the immune system and are effective without causing skin atrophy, as would be caused by a superpotent topical steroid.

RASHES INCURRED IN THE WATER

Seaweed Dermatitis

There are more than 3,000 species of alga, which range in size from 1 micron to 100 meters in length. The blue-green algae Microcoleus lyngbyaceus is a fine, hairlike plant that gets inside the bathing suit of the unwary aquanaut in Hawaiian and Floridian waters, particularly during summer months. Usually, skin under the suit remains in moist contact with the algae (the other skin dries or is rinsed off) and becomes red and itchy, with occasional blistering and/or weeping. The reaction may start a few minutes to a few hours after the victim leaves the water. Treatment consists of a vigorous soap-and-water scrub, followed by a rinse with isopropyl (rubbing) alcohol. Apply hydrocortisone lotion 1% twice a day. If the reaction is severe, oral prednisone may be administered in a dose similar to that for a severe poison oak reaction (see page 234).

Swimmer’s Itch

Swimmer’s itch (clamdigger’s itch) is caused by skin contact with cercariae, which are the immature free-swimming larval forms of parasitic schistosomes (flatworms) found throughout the world in both fresh and salt waters. Snails and birds are the intermediate hosts for the flatworms; the worms do not colonize humans. They release hundreds of fork-tailed microscopic cercariae into the water.

The affliction is contracted when a film of cercaria-infested water dries on exposed (uncovered by clothing) skin. As the water begins to dry, the cercariae penetrate the outer layer of the skin, but die immediately. An allergic response causes itching to be noted within minutes. Each schistosome that enters the skin causes a single red raised spot. Shortly afterward, the skin can become diffusely reddened and swollen, with an intense rash and, occasionally, hives. Blisters may develop over the next 24 to 48 hours. If the area is scratched, it may become infected and the victim develop impetigo (see page 239). Untreated, the affliction is limited to 1 to 2 weeks. Those who have suffered swimmer’s itch previously may be more severely affected on repeated exposures, which suggests that an allergy might be present.

Swimmer’s itch can be prevented by briskly rubbing the skin with a towel immediately after leaving the water, to prevent the cercariae from having time to penetrate the skin. Once the reaction has occurred, the skin should be lightly rinsed with isopropyl (rubbing) alcohol and then coated with calamine or Caladryl lotion. Additional remedies are baking soda or anti-itch oatmeal tub baths. If the reaction is severe, the victim should be treated with oral prednisone as if he suffered from poison oak (see page 234).

Sea Bather’s Eruption

Sea bather’s eruption, often misnamed sea lice (which are true crustacean parasites on fish), occurs in seawater and often involves bathing suit–covered areas of the skin in addition to exposed areas. The skin rash distribution may be similar to that from seaweed dermatitis, but no seaweed is found on the skin. The cause is stings from the nematocysts (stinging cells) of thimble jellyfish, such as Linuche unguiculata, and the larval forms of certain anemones. The victim may notice a tingling sensation on exposed skin or under the bathing suit (breasts, groin, cuffs of wet suits) while still in the water, which is made much worse if he takes a freshwater rinse (shower) while still wearing the suit. The rash usually consists of red bumps, which may become dense and confluent. Itching is severe and may become painful. Treatment is often not optimal, because application of vinegar or rubbing alcohol to stop the envenomation may not be very effective. An agent that may work better is a solution of papain (such as unseasoned meat tenderizer), which may be applied using a mildly abrasive pad. Another remedy that may be effective is lidocaine hydrochloride 4%. After the decontamination and a thorough freshwater rinse, apply hydrocortisone lotion 1% twice a day to treat the inflammatory component of the skin reaction. If the reaction is severe, the victim may suffer from headache, fever, chills, weakness, vomiting, itchy eyes, and burning on urination, and should be treated with oral prednisone as if he suffered from poison oak (see page 234). Topical calamine lotion with 1% menthol may be soothing.

To prevent sea bather’s eruption, an ocean bather or diver should wear, at a minimum, a synthetic nylon-rubber (Lycra [DuPont]) “dive skin.” Safe Sea Sunblock with Jellyfish Sting Protective Lotion (www.buysafesea.com) is both a sunscreen and jellyfish sting inhibitor that may be used to diminish the incidence and severity of jellyfish stings.

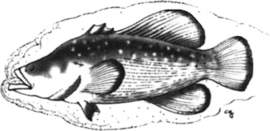

Soapfish Dermatitis

The tropical soapfish Rypticus saponaceous (Figure 121) is covered with a soapy mucus. When exposed to this slime, the victim’s skin becomes red, itches, and undergoes mild swelling. Treatment involves a thorough wash with soap and water, followed by cool compresses, application of calamine lotion, and treatment for a mild allergic reaction similar to that for hives (see page 238).

Fish Handler’s Disease

When cleaning marine fish or shellfish, the handler frequently creates small nicks and scrapes in his skin, usually on his hands. If these become infected with the bacteria Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, a skin rash may develop within 2 to 7 days. The rash appears as a red to violet-colored area of raised skin surrounding the small cut or scrape, with warmth, slight tenderness, and a well-defined border (Figure 122). The sufferer should be treated with penicillin, cephalexin, or ciprofloxacin for 1 week.

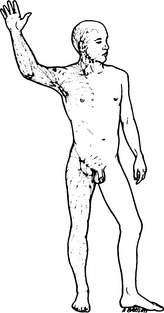

HIVES

Hives are one skin manifestation of an allergic reaction, or may develop as part of a nonallergic reaction (such as to a medication). Hives appear as raised, red, and irregularly bordered welts or thickened patches of skin (Figure 123). Often, the victim will also complain of itching and/or fever. The treatment for hives presumed to be caused by allergy is to administer an antihistamine (such as diphenhydramine [Benadryl]) at 6-hour intervals until the rash has begun to subside and the itching is relieved, and to observe the victim closely for progression to a serious allergic reaction. Hives can appear in moments, yet take days to completely resolve. If the victim complains of shortness of breath or wheezing, or has a swollen tongue (muffled voice) or lips, anticipate a more serious allergic reaction (see page 66). Be prepared to administer epinephrine.

Hives can also be induced by exposure to cold or during rewarming of cold skin (cold urticaria). Accompanying the skin lesions can be fatigue, headache, shortness of breath, rapid heart rate, and, rarely, full-blown anaphylaxis (see page 66). Avoidance of cold may not be totally preventive, since the rate of cooling seems to be as important a factor as the environmental temperature. Avoidance of sudden temperature changes and cold exposure are advised. Certain drugs, such as cyproheptadine (Periactin), may be prescribed by a physician as treatment.

Skin-colored swelling (sometimes severe and called angioedema, indicating fluid collection in the deep skin and subcutaneous tissues) of the lips, eyes, and mucous membranes occurs in 2 to 20 per 10,000 new users of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (a type of drug used to treat hypertension). This is also seen with penicillin allergy and may portend difficulty breathing, so should be treated aggressively, as for a severe allergic reaction (see page 66).

INTERTRIGO

Intertrigo is softening and maceration of skin caused by moisture and rubbing where two skin surfaces are in continual close contact, such as in the creases underneath a woman’s breasts, in the groin, or in skin folds of obese persons. Attempts to keep the area dry are usually unsuccessful in hot and humid environments. To soothe the rash, apply a thin layer of antiseptic ointment, such as bacitracin or mupirocin. If the rash begins to show a white curdish discharge, it may be a yeast infection (see page 133) and may respond to an antifungal preparation.

IMPETIGO

Impetigo is a highly contagious, superficial skin infection caused by the bacteria Staphylococcus, with or without an antecedent Streptococcus infection. It is most often seen in warm and humid climates, and presents as discrete weeping sores, with honey yellow crusted scabs (with or without yellow pus) of the sort often associated with infected insect bites, small scrapes, or areas frequently scratched. The rash may start as pinhead-sized blisters filled with white or yellow pus. Once a few sores have become infected and ruptured, they coalesce and crop up all over the body (particularly in children), and can cause fevers, fatigue, and swollen regional lymph glands. In the blister form of impetigo, the victim shows large, superficial, and fragile blisters that are commonly seen on the trunk, limbs, armpits, and other skinfold areas.

CELLULITIS, INCLUDING METHICILLIN-RESISTANT Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

An increasing cause of cellulitis is methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which can generate prolonged and debilitating infections. These bacteria are resistant to all currently available penicillins and cephalosporins. If MRSA infection is a possibility, the antibiotics of choice in the outdoors are trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, or clindamycin. (Other drugs that may be prescribed by a physician once the diagnosis is confirmed include daptomycin, linezolid, or rifampin, the latter as part of a combination therapy.) The disadvantages of clindamycin are its association with subsequent diarrhea caused by Clostridium difficile and the emergence of bacterial resistance. If trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or a tetracycline is prescribed because of suspicion for a MRSA infection, it is prudent to add a beta-lactam (such as cephalexin) antibiotic to cover possible infection with group A streptococci. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole used alone for MRSA has met with mixed results. Doxycycline and minocycline should not be considered to be automatically effective substitutes for tetracycline. Rifampin is sometimes used in combination with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or doxycycline to treat MRSA infection, but this is not based on scientific data. Fluoroquinolone antibiotics, such as ciprofloxacin (Cipro), should not be used to treat skin and soft-tissue infections caused by community-acquired MRSA, because of bacterial resistance. High-risk persons for MRSA infection include contacts of a person with a MRSA infection, children, male homosexuals, soldiers, prisoners, athletes (especially in contact sports), Native Americans, Pacific Islanders, previously infected individuals, and intravenous drug users. If MRSA is not a consideration (unfortunately, this will increasingly be less the case), antibiotics for cellulitis may include cephalexin, dicloxacillin, or amoxicillin-clavulanate.

If cellulitis is associated with human or animal bite (see page 409), the initial antibiotic should be amoxicillin-clavulanate; if it is associated with exposure to fresh water or salt water (see page 354), ciprofloxacin or doxycycline should be administered along with an antibiotic to cover Staphylococcus; if it is associated with exposure to raw meat, fish or clam processing, or animal handling, infection with Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae (“fish handler’s disease”), should be suspected and the initial antibiotic treatment should include amoxicillin or ciprofloxacin.

ABSCESS

An abscess (boil) is a collection of pus. Although it can occur anywhere on or in the body, it is most frequently noticed on the skin, particularly in an area of high perspiration, friction, and bacteria (particularly Staphylococcus) accumulation, such as associated with hair follicles under the arm (Figure 124) or in the groin. The early abscess first appears as a firm, tender red lump, which progresses over the course of a few days into a reddish-purple, soft, tender, raised area, occasionally with a white or yellowish cap (“comes to a head”) (Figure 125). The surrounding skin is reddened and thickened, and regional lymph glands may be swollen and tender. Fever, swollen lymph glands, and red streaking that travels in a linear fashion from the infected site toward the trunk indicate the spread of infection into the lymphatic system (Figure 126).

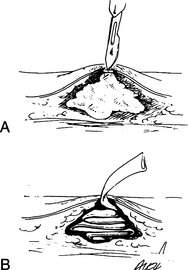

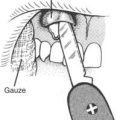

Treatment involves drainage of the pus and dead tissue from within the core of the soft abscess. This is performed by taking a sharp blade and cutting a line into the roof of the abscess at its softest point (Figure 127). The incision must be large enough (generally, at least half the size of the soft area) to allow all of the pus to run out. On rare occasion, the pus inside the abscess will squirt from the incision, so take care to protect your eyes and clothes. After the pus is allowed to drain, the cavity should be rinsed well and then packed snugly with a small piece of gauze to prevent the skin from sealing closed over the created empty space (and thus merely reaccumulating pus, rather than healing). Each day, the packing is removed (yank it out quickly to minimize pain), and the wound irrigated and then repacked until the cavity shrinks to a small size. If the abscess remains open while it is healing such that continuous drainage is assured, packing is not necessary. If the abscess is adequately drained, there is no need to begin antibiotic administration.

If the abscess has not yet softened, but is still red, painful, and hard, begin the victim on warm soaks and administer dicloxacillin, erythromycin, or cephalexin. Continue the soaks until the abscess softens and a white or yellow cap becomes apparent. If the abscess is soft, but there is evidence of lymphatic infection (see above), administer an antibiotic.

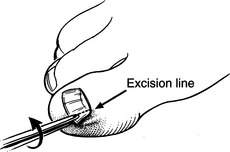

INGROWN TOENAIL

Treatment involves relieving the pressure created by the toenail on the soft tissues that surround it. Soak the affected toe for 30 minutes in a basin or bucket of warm water, preferably with a squirt of disinfectant such as povidone iodine solution. Using a blunt, stiff tweezer, needle driver (see page 269), scissors, or nail clipper, rotate (extract) the ingrown portion of the nail out of the nail bed, and clip (cut) it off (Figure 128). If this is impossible because of pain, which is common when there is an infection, you may need to first administer pain medication. To prevent the nail from growing back into the groove and once again becoming ingrown, layer (pack) the groove with cotton or strips of gauze or clean cloth. Change the packing every few days until the nail has grown back correctly or you can no longer keep the packing in place.

If you don’t have any tools to trim the nail and wish to relieve the pressure, try taking a piece of tape and placing one edge on the soft tissue of the toe against, but not touching, the edge of the ingrown nail (Figure 129). Wrap the tape underneath the toe while pulling, to separate the soft tissue from the nail and relieve the pressure. This is a temporary measure at best.

If there are signs of an infection (see page 240), administer dicloxacillin, cephalexin, or erythromycin for 5 to 7 days and continue the warm- or hot-water soaks two or three times a day.

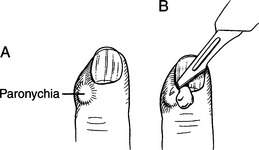

PARONYCHIA

A paronychia is a small abscess (see page 241) at the base of a nail (just beyond the cuticle) in the space between the soft tissue and the nail. It commonly appears as a red or yellowish, soft, and tender swelling in one corner at the base of the nail (Figure 130, A). If the nail feels mobile, there may be an underlying abscess.

If the area is firm, it may not yet be ready for incision and drainage, so begin warm water soaks. To treat a soft or draining paronychia, soak the affected finger in nonscalding hot water with a squirt of disinfectant (such as povidone iodine) for 30 minutes. To drain the collection of pus, you need to slide the tip of a #11 scalpel blade or an 18-gauge needle underneath the cuticle, holding the blade flat against the nail, to puncture the pocket and allow drainage (Figure 130, B). If you don’t have a scalpel, you can use a clean, small knife blade, or even the prong of a fork. Lift the tissue gently off the nail. The abscess will be no more than ¼ in (0.6 cm) below the margin of the cuticle; if you have penetrated that far without the obvious release of pus, cease your digging, start the victim on dicloxacillin, cephalexin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, or erythromycin, and continue with hot-water soaks three times a day. If pus is released, jam a 1 in (2.5 cm) wick of gauze into the pocket, if the victim will tolerate it; with or without the wick, continue the soaks for a few days to keep the pocket draining.

FELON

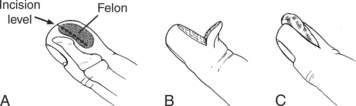

A felon is a severe infection (abscess) of the pulpy tip of a finger (Figure 131, A), usually caused by infection with Staphylococcus or Streptococcus bacteria. It can arise from a nick in the skin, extension of a paronychia, infected hangnail, or puncture wound. The finger becomes swollen and extremely tender, with throbbing pain. Occasionally, there is extension of the infection via the lymphatic system (see page 243), with swollen lymph glands behind the elbow and in the armpit. It is possible to develop a fever with a felon.

Merely soaking the felon in hot water will not help much. The definitive treatment is drainage, but this can be extremely painful. An incision needs to be made that allows extensive drainage from the fingertip. This is usually performed by a physician as a single longitudinal incision through the pad of the fingertip, from the side of the finger into the depth of the pad, completely through the finger with placement of a gauze or rubber “drain,” or by flaying the fingertip pad down from the bony tip of the finger (“fish-mouth incision”) (Figure 131, B and C). Following the incision, warm water soaks are undertaken and antibiotics administered. The victim should be started on dicloxacillin, cephalexin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, or erythromycin.

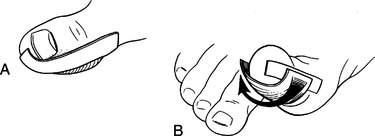

BLISTERS

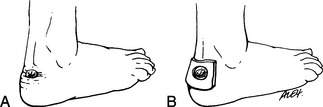

The best protection for a blister is its own roof. Small intact blisters that are not causing significant discomfort should be left intact (Figure 132). To assist in protecting this roof, a small adhesive bandage or pad can be applied. Be certain to place a first layer of paper tape under any cloth adhesive tape, so you do not inadvertently de-roof the blister when removing the tape.

Figure 132 A, Blister on the heel. B, A cushion of moleskin protects the area from further irritation.

The pain from a blister is due to pressure on the incompressible fluid trapped between skin layers. As the abrasion and pressure builds, there is further weakening and separation of skin layers and increased potential for rupturing the blister. When a blister opens, raw skin is exposed. If a blister is punctured with a needle and drained, it will often refill within a few hours. If a large hole is made that allows continuous fluid drainage, there is risk for tearing off the roof and leaving a large damaged area.

If a blister is caused by a thermal burn, it should be immediately immersed in cold water (do not apply ice directly to the burn) for 10 to 15 minutes, to relieve pain and lessen the ultimate injury. Then dry the wound and apply a soft, sterile dressing. Unless there is a reason to suspect infection (cloudy fluid or pus, fever, redness and swelling beyond the blister edges, swollen lymph glands), burn blisters should be left intact (see page 108). Opening an uninfected blister or sticking a needle into it risks introducing bacteria that can cause an infection. Topical antibacterial creams such as silver sulfadiazine or mupirocin, or ointments such as mupirocin or bacitracin, should be applied if the blister is broken, or to prevent the dressing from sticking to the wound. Alternatively, apply a layer of Spenco 2nd Skin or Aquaphor gauze underneath a sterile gauze dressing.

Basic Blister Treatment (for Intact Blisters)

1. Cut moleskin (or a basic blister care product) into a donut of diameter ¼ inch to ⅓ inch around the blister. The blister should fit inside the hole in the donut.

2. Place a patch of Spenco 2nd Skin in the donut hole directly over the blister.

3. Cover the moleskin donut with another layer of moleskin and patch with benzoin and tape.

Note that this “traditional” moleskin/donut treatment may cause further pressure points either directly under the moleskin or by transferring pressure and subsequent increased friction to the opposite side of the foot.

Basic Blister Draining

1. Cleanse both the blister skin and a safety pin with an alcohol pad (the diameter of a safety pin is larger than that of a sewing needle to allow continuous drainage, yet not so large as to risk de-roofing the blister). If alcohol is not available, you may disinfect the needle by heating it to red hot and then allowing it to cool before use.

2. Puncture the blister with the pin at several points at the margin of the blister (generally on the outside of the foot), rather than via one large hole. This will allow natural foot pressure to continually squeeze out fluid, limiting the risk of de-roofing the blister.

3. Gently push out fluid with your fingers.

4. Blot away the expressed fluid.

5. Cover the drained blister with paper tape (protects the blister roof from being torn away when any other overlying tape is removed).

6. Cover the paper tape with benzoin, and then with shaped adhesive tape. All tape should have trimmed and rounded edges to minimize “dog ears” and peeling off.

7. Reaccumulated fluid can be drained through an intact bandage.

Toe Blister

1. Drain the blister with an alcohol-cleansed safety pin.

2. Use one piece of Micropore tape to encircle the toe (leaving the torn tape end at the top of the foot to avoid irritating neighboring toes).

4. Trim sharp edges or wrinkles in the tape. Avoid cloth tape or Elastikon on the toes, as the abrasive nature of these tape varieties may cause blisters on adjacent toes.

To Prevent Blisters

1. Minimize friction generated by the normal biomechanical forces of walking and the contributors to friction. Reduce the carried load, whether that means losing personal weight or shedding pounds from the backpack. Use a padded insole or arch support to help evenly distribute pressure over the bottom surface of the foot.

2. Increase or decrease the ease with which two surfaces rub against each other.

3. Shoes or boots should fit properly and comfortably. Shoes that are too tight increase contact points of pressure on the foot. Those that are too loose allow excess movement that allows generation of friction. Overly narrow shoes typically cause blisters on the large and small toes. Loose shoes can create blisters on the tips of toes from sliding and jamming the tips into the toe box. A toe box that is too shallow can cause blisters on the tops of the toes.

4. Fit (size) shoes in the evening, because feet tend to swell throughout the day. When trying on shoes or boots, make sure to wear the same socks and/or insoles or orthotics that you will be using on the trails. Size boots to compensate for thicker socks.

5. Allow for ample time to break in new footwear. This will stretch the material, sometimes loosen it, and increase flexibility. The breaking-in period also conditions the skin itself by causing the outermost layer to thicken.

6. Soft and supple feet are better able to withstand frictional stress than are cracked and horny feet. Many podiatrists recommend preparing feet with Bag Balm, a moisturizer, petrolatum, or other softening agent. Calluses should be filed down and toenails kept trimmed short and beveled downward.

7. Create a weak shear layer using two pairs of socks. The goal is to have friction occur between the two layers of socks, not between the skin and the socks. Wear a smooth, thin, snug-fitting synthetic sock worn as an inner layer with a thick, woven sock worn as an outer layer. The thinner synthetic liner sock will also assist in moisture control by wicking moisture and perspiration away from the skin surface.

8. Barriers are best utilized as preventive measures before blisters form, either at the beginning of the day or as soon as a hot spot develops. The barrier needs to be adhesive so it can remain fixed to skin, despite the action of friction, warmth, and/or moisture. Blist-O-Ban bandages (SAM Medical Products), Micropore paper tape, cloth tape, Elastikon elastic tape, moleskin, Spenco Blister Pads, Band-Aid Blister Block, and duct tape are methods to prevent blister development. Using an adhesive such as tincture of benzoin or Pedi-Pre Tape Spray will help keep the barrier adherent to the skin.

9. A cardinal rule of taping is to smooth out any wrinkles, and cut off “dog ears” that may lead to further pressure points. ENGO Blister Prevention Patches are slick fabric-film composite patches that are placed on the inside of the shoe or insole. Silicon gel toecaps and sheaths reduce friction between the toes.

10. Keep the skin clean and dry to minimize friction. Skin hydration leads to increasing contact area and friction, so moist skin results in more frequent blisters. However, very wet skin has a low incidence of blister formation, likely due to the lubricating effects of water on the skin surface. High-technology oversocks combine waterproof materials with traditional socks to help keep feet dry when repeatedly exposed to water. Combining GORE-TEX oversocks with wicking liner socks and foot antiperspirant is a method to reduce foot moisture. If your feet are often moist or sweaty, change socks frequently.

11. Consider the addition of gaiters to help eliminate dirt, gravel, sand, and rocks from entering the sock-shoe system.

12. Drying powders decrease moisture for short periods of time and are useful in the evening to dry out feet, but after about 1 hour may actually increase the friction between surfaces. Lubricants have been developed that are more advanced than traditional Vaseline, which is greasy and tends to trap grit particles, which are irritating and may increase friction and blister production. Advanced lubricants that combine silicone and petrolatum have a silky feel, prevent friction, and repel moisture from the skin. Lubricants can be applied preemptively, or over tape when hot spots develop. However, after about 3 hours, friction is increased as the lubricants are absorbed into the skin and socks. Lubricants should be tested before use on the trail to assess for allergic reaction, and if used, reapplied frequently.

13. Antiperspirants irritate and block sweat ducts, reducing the amount of perspiration. People who suffer from a condition called hyperhidrosis experience excessive foot perspiration and subsequently have extremely moist feet. These people may benefit the most from antiperspirants.

14. Blisters or reddened skin may also be caused by an allergic (“contact”) reaction to chemicals such as formaldehyde or rubber. If a rash is confined to the soles of the feet (shoe inserts) or top of the feet (shoe tongue dye), suspect this problem. In this case, the footgear must be changed.

ATHLETE’S FOOT, RINGWORM, AND JOCK ITCH

These rashes are more common in summer, particularly among those who do a lot of sweating and bathe infrequently. They are managed with antifungal cream (terbinafine 1% [Lamisil], butenafine [Lotrimin Ultra], ketoconazole 2% [Nizoral], econazole [Spectazole], or miconazole [Micatin or Lotrimin AF]) and antifungal powder, such as tolnaftate (Tinactin) or clotrimazole 1% (Lotrimin), applied two or three times a day. If the rash is refractory to topical therapy, a physician can prescribe an oral antifungal agent. Because a fungal infection is contagious, socks and underwear should not be shared. If possible, wear cotton underclothing that absorbs sweat.

ONYCHOMYCOSIS

Prevention involves excellent foot hygiene and avoidance of fungal infection between the toes (athlete’s foot) (see page 251). If possible, wash and dry your feet each day. To control foot sweating—which leads to blisters, fungal infections, and foot odor—spray your feet daily with an aluminum chlorhydrate antiperspirant, unless a fissure or crack appears in the skin, in which case spraying must be discontinued until the skin is healed. An alternative is to use a drying, deodorant foot powder. Each day, gently massage your feet and apply antifungal powder. Keep your nails trimmed. When hiking, use two pairs of socks—an inner thin liner sock of polypropylene or polyester and a thicker outer sock densely woven from a wool (or similar material) blend.

LICE

One percent permethrin cream rinse (Nix) or 0.5% malathion lotion (Ovide; approved for age 2 years and older) is also effective for removing lice from the hair. Apply it after the hair has been washed and towel-dried, leave it on for 10 to 20 minutes, and then rinse it off. Use a fine-toothed comb to remove the nits after rinsing. Comb again in 1 to 2 days. Repeat the treatment in 7 days to eliminate emerging lice. A treatment for resistant head and body lice is 0.3% pyrethium and 3% piperonyl butoxide (R and C shampoo, or RID) applied to all affected areas and washed off after 10 minutes. Pubic lice may be treated with the same medications used for head lice.

SHINGLES

Shingles is the common name for herpes zoster, a skin eruption with activation often related to stress. Individuals carry the varicella-zoster virus (the same agent that causes chicken pox [varicella] in children) “silently” in nerve roots. On stimulation, usually in an elderly individual or someone with impaired immunity, it causes the outcropping of a series of blisters in patterns that correspond with skin areas served by particular nerve roots originating from the spinal cord (Figure 133). Classically, the victim will have a day or two of unexplained itching or burning pain in the area that is going to break out, and then will notice the onset of the rash, which appears as crops of clear blisters over 3 to 5 days. Symptoms that occur before the appearance of the rash often include headache, aversion to light, and fatigue. The discomfort can be tremendous and may necessitate liberal use of pain medication. The rash itself should be kept clean and dry, and covered with a light, dry dressing to prevent further irritation from rubbing or the sun.