Chapter 24 Skin disease

Structure and function of the skin

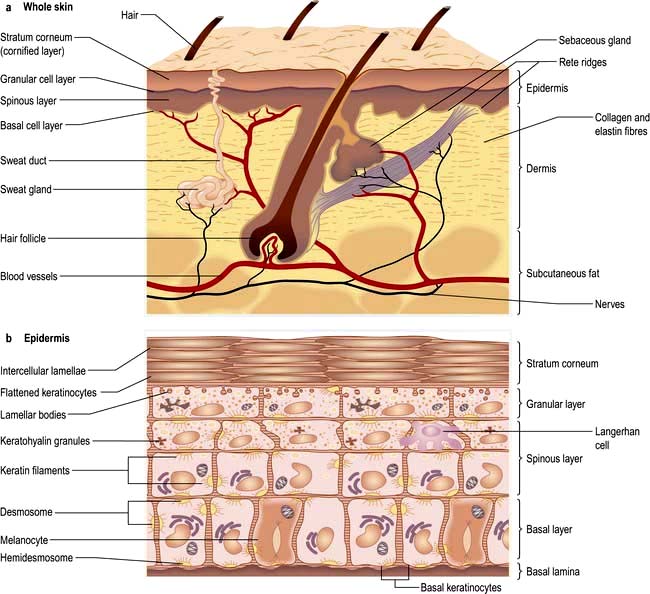

The skin consists of four distinct layers:

The functions of the skin are summarized in Box 24.1.

![]() Box 24.1

Box 24.1

Functions of the skin

Physical barrier against friction and shearing forces

Physical barrier against friction and shearing forces

Protection against infection (immune and innate), chemicals, ultraviolet irradiation

Protection against infection (immune and innate), chemicals, ultraviolet irradiation

Prevention of excessive water loss or absorption

Prevention of excessive water loss or absorption

Ultraviolet-induced synthesis of vitamin D

Ultraviolet-induced synthesis of vitamin D

Sensation (pain, touch and temperature)

Sensation (pain, touch and temperature)

Basement membrane zone

The basement membrane zone (see Fig. 24.27) is a complex proteinaceous structure consisting of type IV, VII and XVII collagen, hemidesmosomal proteins, integrins and laminin. Collectively, they hold the skin together, keeping the epidermis firmly attached to the dermis. Inherited or autoimmune-induced deficiencies of these proteins can cause skin fragility and a variety of blistering diseases (see p. 1221).

The dermis

The sweat glands

Eccrine sweat glands are found throughout the skin except the mucosal surfaces.

The sweat glands and vasculature are involved in temperature control.

The subcutaneous layer

FURTHER READING

Borkowski AW, Gallo RL. The coordinated response of the physical and antimicrobial peptide barriers of the skin. J Invest Dermatol 2011; 131:285–287.

Lin JY, Fisher DE. Melanocyte biology and skin pigmentation. Nature 2007; 445:843–850.

Shimomura Y, Christiano AM. Biology and genetics of hair. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 2010; 11:109–132.

Approach to the patient

The history should aim to elicit the following points:

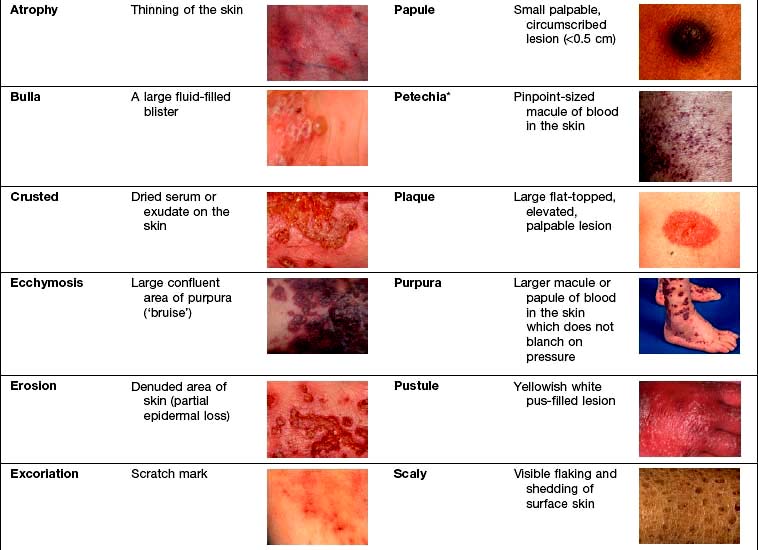

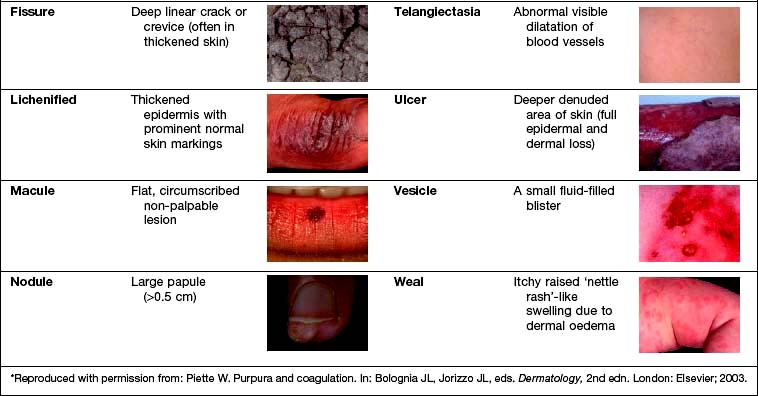

Examination entails looking and feeling a rash (for terminology, see Table 24.1). It should include an assessment of nails, hair and mucosal surfaces even if these are recorded as unaffected. The following terms are used to describe distribution: flexural, extensor, acral (hands and feet), symmetrical, localized, widespread, facial, unilateral, linear, centripetal (trunk more than limbs), annular and reticulate (lacey network or mesh like).

Investigation. With regard to investigation, clinical acumen remains the most useful tool in dermatology but a variety of tests are useful in confirming a diagnosis (Table 24.2).

| Test | Use | Clinical example |

|---|---|---|

|

Skin swabs |

Bacterial culture |

Impetigo |

|

Blister fluid |

Electron microscopy, viral culture and PCR |

Herpes simplex |

|

Skin scrapes |

Fungal culture |

Tinea pedis |

|

Microscopy |

Scabies |

|

|

Nail sampling |

Fungal culture |

Onychomycosis |

|

Wood’s light |

Fungal fluorescence |

Scalp ringworm |

|

Erythrasma |

||

|

Blood tests |

Serology |

Streptococcal cellulitis |

|

Autoantibodies |

Systemic lupus erythematosus |

|

|

HLA typing |

Dermatitis herpetiformis |

|

|

DNA analysis |

Epidermolysis bullosa |

|

|

Skin biopsy |

Histology |

General diagnosis |

|

Immunohistochemistry |

Cutaneous lymphoma |

|

|

Immunofluorescence |

Immunobullous disease |

|

|

Culture |

Mycobacteria/fungi |

|

|

Patch tests |

Allergic contact eczema |

Hand eczema |

|

Urine |

Dipstick (glucose) |

Diabetes mellitus |

|

Cytology (red cells) |

Vasculitis |

|

|

Dermatoscopy (direct microscopy of skin) |

Assessment of pigmented lesions |

Malignant melanoma |

Infections

Bacterial infections (see also p. 114)

Impetigo

Impetigo is a highly infectious skin disease most common in children (Fig. 24.2). It presents as weeping, exudative areas with a typical honey-coloured crust on the surface. It is spread by direct contact. The term ‘scrum pox’ refers to impetigo spread between rugby players. Staphylococci or group A β-haemolytic streptococci are the causative agents: skin swabs should be taken.

Treatment

Impetigo is usually treated with oral antibiotics for 7–10 days (flucloxacillin 500 mg four times daily for Staphylococcus; phenoxymethylpenicillin 500 mg four times daily for Streptococcus). Other close contacts should be examined and children should avoid school for 1 week after starting therapy. If impetigo appears resistant to treatment or recurrent, take nasal swabs and check other family members. Nasal mupirocin (three times daily for 1 week) is useful to eradicate nasal carriage, especially in hospital staff. Community-acquired MRSA (in chapter 4) is increasingly recognized as a cause of superficial skin infections and treatment should be governed by bacterial sensitivities.

Bullous impetigo/staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Rarely Staphylococcus releases an exfoliating toxin which acts high up in the epidermis: toxin A causes blistering at the site of infection (bullous impetigo), toxin B spreads through the body causing more widespread blistering (staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, SSSS). The latter is more common in childhood with very low mortality rates. In adults it is often associated with renal disease or immunosuppression, and mortality rates increase to 50%. Both these toxins cleave desmoglein 1 (a desmosomal protein) so mucosal involvement does not occur (this is analogous to pemphigus foliaceous which has the same target antigen, p. 1222).

SSSS can mimic toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN, see p. 1231). It can be differentiated in two ways: mucosal involvement only occurs in TEN, and skin biopsy shows a more superficial split in SSSS (intraepidermal) than in TEN (subepidermal). Both bullous impetigo and SSSS are treated with anti-staphylococcal antibiotics (e.g. flucloxacillin) and supportive care.

Cellulitis

Cellulitis presents as a hot, sometimes tender area of confluent erythema of the skin due to infection of the deep subcutaneous layer. It often affects the lower leg, causing an upward-spreading, hot erythema, and occasionally will blister, especially if oedema is prominent. It may also be seen affecting one side of the face. Patients are often unwell with a high temperature. It is usually caused by a β-haemolytic streptococcus, rarely a staphylococcus, and sometimes community-acquired MRSA (in chapter 4). In the immunosuppressed or diabetic patient Gram-negative organisms or anaerobes should be suspected.

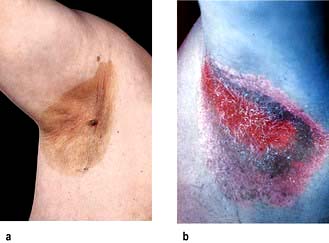

Erythrasma

Erythrasma is caused by Corynebacterium minutissimum. It usually presents as an orange-brown flexural rash, and is often seen in the axillae or toe web spaces (Fig. 24.3). It is frequently misdiagnosed as a fungal infection. The rash shows a dramatic coral pink fluorescence under Wood’s (ultraviolet) light.

Treatment is with oral erythromycin 500 mg four times daily for 7–10 days.

Hidradenitis suppurativa

Treatment is difficult but weight loss, ‘prophylactic’ antibiotics, oral retinoids, zinc and co-cyprindiol (2 mg cyproterone acetate + 35 µg ethinylestradiol in females only) have been tried. They should be used as for acne vulgaris (p. 1212). Severe recalcitrant cases have been treated with intravenous infliximab, a monoclonal antibody (p. 72). Surgery and skin grafting is sometimes required.

Mycobacterial infections

Leprosy (Hansen’s disease) (p. 130)

Tuberculoid leprosy presents with a few larger, hypopigmented (see Fig. 4.28) or erythematous plaques with an active erythematous, often raised, rim. Lesions are usually markedly anaesthetic, dry and hairless, reflecting the nerve damage. Nerves may be enlarged and palpable. Biopsy shows a granulomatous infiltrate centred on nerves but no organisms.

Skin manifestations of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis can occasionally cause skin manifestations:

Lupus vulgaris usually arises as a post-primary infection. It usually presents on the head or neck with red-brown nodules that look like apple jelly when pressed with a glass slide (‘diascopy’). They heal with scarring and new lesions slowly spread out to form a chronic solitary erythematous plaque. Chronic lesions are at high risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma.

Lupus vulgaris usually arises as a post-primary infection. It usually presents on the head or neck with red-brown nodules that look like apple jelly when pressed with a glass slide (‘diascopy’). They heal with scarring and new lesions slowly spread out to form a chronic solitary erythematous plaque. Chronic lesions are at high risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma.

Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis arises in people who are partially immune to tuberculosis but who suffer a further direct inoculation in the skin. It presents as warty lesions on a ‘cold’ erythematous base.

Tuberculosis verrucosa cutis arises in people who are partially immune to tuberculosis but who suffer a further direct inoculation in the skin. It presents as warty lesions on a ‘cold’ erythematous base.

Scrofuloderma arises when an infected lymph node spreads to the skin causing ulceration, scarring and discharge.

Scrofuloderma arises when an infected lymph node spreads to the skin causing ulceration, scarring and discharge.

The tuberculides are a group of rashes caused by an immune manifestation of tuberculosis rather than direct infection. Erythema nodosum is the commonest and is discussed on page 1216. Erythema induratum (‘Bazin’s disease’) produces similar deep red nodules but these are usually found on the calves rather than the shins and they often ulcerate.

The tuberculides are a group of rashes caused by an immune manifestation of tuberculosis rather than direct infection. Erythema nodosum is the commonest and is discussed on page 1216. Erythema induratum (‘Bazin’s disease’) produces similar deep red nodules but these are usually found on the calves rather than the shins and they often ulcerate.

Viral infections

Viral exanthem

This is the commonest type of virus-induced rash and presents clinically as a widespread nonspecific erythematous maculopapular rash. It probably arises due to circulating immune complexes of antibody and viral antigen localizing to dermal blood vessels. The rash can be caused by many different viruses (e.g. echovirus, erythrovirus, human herpes virus-6, Epstein–Barr virus; see chapter 4) and so is rarely diagnostic. The rash will resolve spontaneously in 7–10 days.

Herpes simplex virus (see also p. 97)

HSV type 2 infections are discussed on page 97. Other rare complications of HSV infection include corneal ulceration, eczema herpeticum, chronic perianal ulceration in AIDS patients and erythema multiforme.

Varicella zoster virus

Varicella zoster virus (VZV) causes the common childhood infection called chickenpox. It is discussed on page 98. It also causes herpes zoster.

Herpes zoster (shingles)

‘Shingles’ results from a reactivation of VZV. It may be preceded by a prodromal phase of tingling or pain, which is then followed by a painful and tender blistering eruption in a dermatomal distribution (Fig. 24.4 and Fig. 4.15, p. 98). The blisters occur in crops, may become pustular and then crust over. The rash lasts 2–4 weeks and is usually more severe in the elderly. Occasionally more than one dermatome is involved.

Human papilloma virus

Human papilloma virus (HPV) is responsible for the common cutaneous infection of ‘viral warts’.

Common warts are papular lesions with a coarse roughened surface, often seen on the hands and feet, but also on other sites. Small black dots (bleeding points) are often seen within the lesion (Fig. 24.5). If they occur on the face they are often elongated (‘filiform’) Children and adolescents are usually affected. Spread is by direct contact and is also associated with trauma.

Molluscum contagiosum (‘water blisters’)

Molluscum contagiosum is a common cutaneous infection of childhood caused by the pox virus. Clinically, lesions are multiple small (1–3 mm) translucent papules which often look like fluid-filled vesicles but are in fact solid. Individual lesions may have a central depression called a punctum. They exhibit the Köbner phenomenon (p. 1208). They can occur at any body site including the genitalia. Transmission is by direct contact. Occasionally lesions may be up to 1 cm in diameter (‘giant molluscum’).

Fungal infections

Dermatophyte infection

Tinea cruris

Ringworm of the groin is extremely common worldwide. Early on, the lesions appear as well-demarcated red plaques with an arc-like border extending down the upper thigh (Fig. 24.6). Central clearing may appear and a few pustules or vesicles may be seen if inflammation is intense. Satellite lesions, suggestive of Candida, are not present.

Tinea unguium

Ringworm of the nails is increasingly common with age and frequently ignored as it is often asymptomatic. Clinically this presents as asymmetrical whitening (or yellowish black discoloration) of one or more nails which usually starts at the distal or lateral edge before spreading throughout the nail (Fig. 24.7). The nail plate appears thickened. Crumbly white material appears under the nail plate and this is the best fungal infections specimen to obtain for mycology sampling. The nail plate may become destroyed with advanced disease.

Candida albicans

Candida albicans (see also p. 170) is a yeast that is sometimes found as part of the body’s flora, especially in the gastrointestinal tract. It acts as an opportunist, taking hold in the skin when there is a suitable warm moist environment such as in nappy rash (p. 1234) or intertrigo in obese individuals (Fig. 24.8).

Infestations

Scabies

Scabies is spread by prolonged close contact such as within households or institutions, and by sexual contact. It presents clinically with itchy red papules (or occasionally vesicles and pustules) which can occur anywhere in the skin but rarely on the face, except in neonates. The distribution of lesions is often suggestive of the diagnosis (Fig. 24.9). Sites of predilection are between the web spaces of the fingers and toes, on the palms and soles, around the wrists and axillae, on the male genitalia, and around the nipples and umbilicus.

Treatment

All the skin below the neck should be treated, including the genitalia, palms and soles, and under the nails. Treat the head and neck regions in infants (up to age 2 years).

All the skin below the neck should be treated, including the genitalia, palms and soles, and under the nails. Treat the head and neck regions in infants (up to age 2 years).

All close contacts should be treated at the same time even if asymptomatic.

All close contacts should be treated at the same time even if asymptomatic.

Reapply scabicide to the hands if they are washed during the treatment period.

Reapply scabicide to the hands if they are washed during the treatment period.

Washing or cleaning of recently worn clothes (preferably at 60°C) is recommended to avoid reinfection.

Washing or cleaning of recently worn clothes (preferably at 60°C) is recommended to avoid reinfection.

Patients should be warned that the pruritus may persist for up to 4 weeks after successful treatment.

Patients should be warned that the pruritus may persist for up to 4 weeks after successful treatment.

Arthropod-borne diseases (‘insect bites’ or papular urticaria)

Infestations with bed bugs have increased enormously in the past decade in the developed world. They can be seen as small brown/black lentil-sized insects at night-time as they are attracted to warmth and carbon dioxide of sleeping humans. Infestations require professional insecticide treatments of properties. Advice can be obtained from the National Pest Technicians Association (www.npta.org.uk).

Papulo-squamous/inflammatory rashes

Eczema

Introduction

All eczemas (Table 24.3) have some features in common and there is a spectrum of clinical presentation from acute through to chronic. Vesicles or bullae may appear in the acute stage if inflammation is intense. In subacute eczema the skin can be erythematous, dry and flaky, oedematous and crusted (especially if secondarily infected). Chronic persistent eczema is characterized by thickened or lichenified skin. Eczema is nearly always itchy. Histologically ‘eczematous change’ refers to a collection of fluid in the epidermis between the keratinocytes (‘spongiosis’) and an upper dermal perivascular infiltrate of lymphohistiocytic cells. In more chronic disease there is marked thickening of the epidermis (‘acanthosis’).

| Endogenous | Exogenous |

|---|---|

Atopic eczema

This type of eczema (‘endogenous eczema’) occurs in individuals who are ‘atopic’ (p. 823). It is common, occurring in up to 5% of the UK population. It is commoner in early life, occurring at some stage during childhood in up to 10–20% of all children.

Aetiology

Exacerbating factors

FURTHER READING

Batchelor JM, Grindlay DJ, Williams HC. What’s new in atopic eczema? An analysis of systematic reviews published in 2008 and 2009. Clin Exp Dermatol 2010; 35:823–828.

Bieber T. Mechanisms of disease: atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:1483–1494.

Brown SJ, McLean WH. Eczema genetics: current state of knowledge and future goals. J Invest Dermatol 2009; 129:543–552.

Irvine AD et al. Filaggrin mutations associated with skin and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:1315–1327.

Clinical features

Atopic eczema can present as a number of distinct morphological variants. The commonest presentation is of itchy erythematous scaly patches, especially in the flexures such as in front of the elbows and ankles, behind the knees (Fig. 24.10) and around the neck. In infants eczema often starts on the face before spreading to the body. Very acute lesions may weep or exude and can show small vesicles. Scratching can produce excoriations, and repeated rubbing produces skin thickening (lichenification) with exaggerated skin markings.

Treatment (Box 24.2)

Topical therapies

Topical therapies (p. 1235) are sufficient to control atopic eczema in most people. The ‘triple’ combination of topical steroid, frequent emollients (see Table 24.18) and bath oil and soap substitute (e.g. aqueous cream) helps.

| Greasy emollients | Lighter creams |

|---|---|

|

Epaderm ointmenta |

E45 creama |

|

Oily cream |

Diprobase creama |

|

Unguentum Mercka |

Aveeno creama |

|

50:50 white soft paraffin/liquid paraffin |

Aqueous cream |

Use of topical steroids. Unjustified fear about the dangers of topical steroids has often led to undertreatment of eczema. Providing appropriate-strength steroid preparations are used for the right body site, these compounds can be used quite safely on a long-term intermittent basis. Topical steroids can be divided into five groups depending on their potency (Table 24.4).

Table 24.4 Classification of topical steroids by potency

|

Very potent |

0.05% clobetasol propionate |

|

0.3% diflucortolone valerate |

|

|

Potent |

0.1% betamethasone valerate |

|

0.025% fluocinolone acetonide |

|

|

Diluted potent |

0.025% betamethasone valerate |

|

0.00 625% fluocinolone acetonide |

|

|

Moderately potent |

0.05% clobetasone butyrate |

|

0.05% alclometasone dipropionate |

|

|

Mild |

2.5% hydrocortisone |

|

1% hydrocortisone |

The face should be treated only with mild steroids.

The face should be treated only with mild steroids.

In adults the body should be treated with either mild, moderately potent or diluted potent steroids.

In adults the body should be treated with either mild, moderately potent or diluted potent steroids.

In young children the body should be treated with mild and moderately potent steroids.

In young children the body should be treated with mild and moderately potent steroids.

Potent steroids are used for short courses (7–10 days).

Potent steroids are used for short courses (7–10 days).

Treatment of the palms and soles (but not the dorsal surfaces) may require potent or very potent steroids as the skin is much thicker.

Treatment of the palms and soles (but not the dorsal surfaces) may require potent or very potent steroids as the skin is much thicker.

Regular use of emollients may lessen the need for steroid use.

Regular use of emollients may lessen the need for steroid use.

Only use steroids on inflamed skin. Do not use as an emollient.

Only use steroids on inflamed skin. Do not use as an emollient.

‘Apply sparingly’ means use sufficient to leave a glistening surface to the skin after application.

‘Apply sparingly’ means use sufficient to leave a glistening surface to the skin after application.

Use weaker steroid preparations in flexures (e.g. the groin, and under breasts) as apposition of the skin at these sites tends to occlude the treatment and increase absorption.

Use weaker steroid preparations in flexures (e.g. the groin, and under breasts) as apposition of the skin at these sites tends to occlude the treatment and increase absorption.

Sedating antihistamines

These (e.g. oral hydroxyzine hydrochloride 10–25 mg) are useful at night-time.

Second-line agents

These are used in severe non-responsive cases, especially if the eczema is significantly interfering with an individual’s life (e.g. growth, sleeping, schoolwork or job). Ultraviolet phototherapy (see p. 1215), prednisolone (initial doses up to 30 mg daily), ciclosporin (3–5 mg/kg daily) and azathioprine (1–3 mg/kg daily) (in chapter 6) can all be effective treatments. However they all have side-effects and the risk/benefit ratio must be openly discussed with the patient before they are used.

Hand eczema

Eczema may be confined to the hands (and feet). It can present with:

Seborrhoeic eczema

Clinical features

In neonates it is common and presents as yellowish thick crusts on the scalp (cradle cap). A more widespread erythematous, scaly rash can be seen over the trunk, especially affecting the nappy area. Unlike with atopic eczema, the child is normally unbothered as there is little associated pruritus. The rash normally improves spontaneously after a few weeks.

In neonates it is common and presents as yellowish thick crusts on the scalp (cradle cap). A more widespread erythematous, scaly rash can be seen over the trunk, especially affecting the nappy area. Unlike with atopic eczema, the child is normally unbothered as there is little associated pruritus. The rash normally improves spontaneously after a few weeks.

In young adults (especially males) it occurs in 1–3% of the population. The rash is more persistent and presents as an erythematous scaling along the sides of the nose (Fig. 24.12), in the eyebrows, around the eyes and extending into the scalp (which shows marked dandruff). It may affect the skin over the sternum, axillae and groins, and the glans penis. A blepharitis may also be present.

In young adults (especially males) it occurs in 1–3% of the population. The rash is more persistent and presents as an erythematous scaling along the sides of the nose (Fig. 24.12), in the eyebrows, around the eyes and extending into the scalp (which shows marked dandruff). It may affect the skin over the sternum, axillae and groins, and the glans penis. A blepharitis may also be present.

In elderly people seborrhoeic eczema can be more severe and progress to involve large areas of the body and even cause erythroderma.

In elderly people seborrhoeic eczema can be more severe and progress to involve large areas of the body and even cause erythroderma.

Venous eczema (varicose eczema, gravitational eczema)

This type of eczema occurs on the lower legs due to chronic venous hypertension (usually of more than 2 years’ duration) (see p. 1226).

Allergic contact and irritant contact eczema

If the eczema is in an unusual or localized distribution (Fig. 24.13), especially if there is no personal or family history of atopic disease, one of a variety of environmental agents (exogenous eczema) is the likely cause. A history of an exacerbation of eczema at the workplace is also suggestive (‘occupational dermatitis’). There are two possible mechanisms: direct irritation or an allergic reaction (type IV delayed hypersensitivity). A detailed history of occupation, hobbies, cosmetic products, clothing and contact with chemicals is necessary.

Lichen simplex/nodular prurigo (neurodermatitis)

Lichen simplex appears as thickened, scaly and hyperpigmented areas of lichenification (Fig. 24.14). It starts with intense itching that becomes tender with increased rubbing or scratching, and a self-perpetuating ‘itch-scratch cycle’ develops. It is rare before adolescence and is commoner in females. Common sites are the nape of the neck, the lateral calves, the upper thighs, the upper back and the scrotum or vulva but any accessible site can be affected.

The diagnosis is made by exclusion of other pathologies and may require a skin biopsy. General medical causes of pruritus should be excluded including HIV infection (p. 154 and p. 177). In the elderly, nodular prurigo may be an early sign of bullous pemphigoid, before the more typical blistering phase has appeared.

Treatment

Treatment is often difficult as symptoms can be intractable. Very potent topical steroids (e.g. 0.05% clobetasol propionate) with occlusive tar bandaging may sometimes help. Intralesional steroids can also be useful but there is a risk of atrophy. For resistant cases (especially of prurigo lesions) topical doxepin, phototherapy (p. 1215), low-dose oral amitriptyline (50 mg nightly) and ciclosporin (3–5 mg/kg per day) are used.

Psoriasis

Aetiology

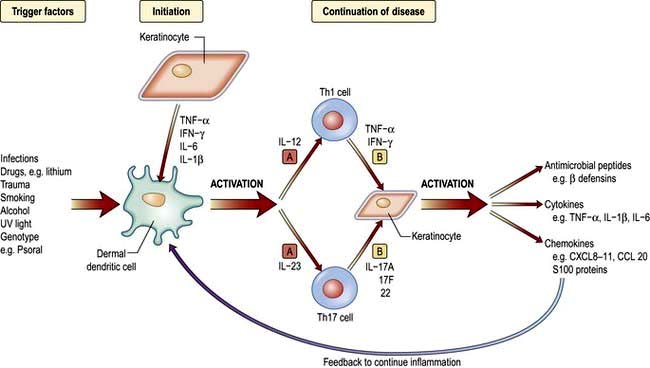

The exact aetiology is unknown but evidence suggests that psoriasis is a T-lymphocyte-driven disorder to an unidentified antigen(s). Figure 24.15 shows the trigger factors that activate the antigen-presenting cell (dendritic/Langerhans). This activation results in upregulation of Th1-type T cell cytokines, e.g. interferon-γ, interleukins (IL-1, -2, -8), growth factors (TGF-α and TNF-α) and adhesion molecules (ICAM-1). The pro-inflammatory cytokine TNF-α is also produced by keratinocytes and this may be involved in both initiation and maintenance of psoriatic lesions. TNF-α blocking drugs have proved highly effective in treatment (Fig. 24.15). IL-17 and IL-22 are thought to work together to produce clinical psoriasis (see p. 1210).

Clinical features

Chronic plaque psoriasis

This is the ‘common’ type of psoriasis. It is characterized by pinkish red scaly plaques, with a silver scale seen, especially on extensor surfaces such as knees (Fig. 24.16a) and elbows. The lower back, ears and scalp are also commonly involved. New plaques of psoriasis occur at sites of skin trauma – the so-called ‘Köbner phenomenon’. The lesions can become itchy or sore.

Guttate psoriasis

‘Raindrop-like’ psoriasis is a variant most commonly seen in children and young adults (Fig. 24.16b). An explosive eruption of very small circular or oval plaques appears over the trunk about 2 weeks after a streptococcal sore throat.

Associated features

Nails. Up to 50% of individuals with psoriasis develop nail changes (Fig. 24.17) and rarely these can precede the onset of skin disease. There are five types of nail change: (a) pitting of the nail plate; (b) distal separation of the nail plate (onycholysis); (c) yellow-brown discoloration; (d) subungual hyperkeratosis; (e) rarely a damaged nail matrix and lost nail plate. Treatment of nail dystrophy is very difficult.

Figure 24.17 Psoriasis of the nail – yellowish brown discoloration and distal nail plate separation (onycholysis).

Arthritis. Some 5–10% of individuals develop psoriatic arthritis and most of these will have nail changes (p. 602).

Guttate psoriasis is usually treated with topical therapies and/or UVB phototherapy.

Erythrodermic psoriasis also requires systemic therapy (but not phototherapy) as well as general supportive measures (p. 1215).

All systemic treatments must be monitored for toxicity.

Use of methotrexate. Methotrexate is normally given once weekly. Some patients experience severe nausea on the day they take it which can be lessened by folic acid therapy. Both men and women should avoid conception during and for 3 months after therapy. Some patients are allergic to methotrexate and develop a pyrexia and mouth ulceration. Regular blood tests need to be done to monitor for bone marrow suppression and liver damage. Alcohol must be avoided as this increases the risk of hepatotoxicity. NSAIDs should also be avoided as these inhibit excretion. Lower doses should be used in the elderly. Long-term use causes hepatic fibrosis, and regular monitoring of patients’ serum procollagen III peptide level or elastography (p. 327) is being used to assess fibrosis development. People with concomitant psoriatic arthritis are more likely to develop pulmonary fibrosis.

Cytokine modulators (see Fig. 24.15)

Etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab (TNF-α blockers) are highly effective and tend to be used first-line in the UK as they have the longest safety data.

Etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab (TNF-α blockers) are highly effective and tend to be used first-line in the UK as they have the longest safety data.

Ustekinumab (a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody) is highly effective. Its safety data is limited so it is most commonly used in those patients that fail a TNF-α blocker.

Ustekinumab (a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody) is highly effective. Its safety data is limited so it is most commonly used in those patients that fail a TNF-α blocker.

Alefacept (a dimeric fusion protein that blocks LFA-3/CD2 interaction on T cells) is somewhat less effective and has been licensed for use in North America and Australia but not Europe. CD4 counts must be checked during therapy.

Alefacept (a dimeric fusion protein that blocks LFA-3/CD2 interaction on T cells) is somewhat less effective and has been licensed for use in North America and Australia but not Europe. CD4 counts must be checked during therapy.

Brikinumab, a monoclonal antibody against the p40 molecule shared by IL-12 and IL-23, is effective in moderate and severe psoriasis.

Brikinumab, a monoclonal antibody against the p40 molecule shared by IL-12 and IL-23, is effective in moderate and severe psoriasis.

Brodalumab (an anti-IL-17 receptor antibody) and ixekizumab (an anti-IL-17 monoclonal antibody) have recently been shown to be effective in psoriasis.

Brodalumab (an anti-IL-17 receptor antibody) and ixekizumab (an anti-IL-17 monoclonal antibody) have recently been shown to be effective in psoriasis.

All these agents are given by injection and are very expensive. Long-term side-effects of these new agents are unknown. TNF-α blockers’ side-effects are discussed on page 524. One biologic drug (efalizumab) has been withdrawn due to the risk of prion brain disease.

FURTHER READING

Griffiths CE, Strober BE, van de Kerkhof P et al. Comparison of ustekinumab and etanercept for moderate-to-severe psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2010; 362:118–128.

Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Section 6. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 65:137–174.

Nestle FO, Kaplan DH, Barker J. Psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:496–509.

Urticaria and angio-oedema

Urticaria (hives, ‘nettle rash’) is a common skin condition characterized by the acute development of itchy weals or swellings in the skin due to leaky dermal vessels (Fig. 24.18). Angio-oedema is a similar condition but involves sub-dermal vessels.

Clinical features

Physical urticarias

Occasionally, urticaria can be caused by physical stimuli such as cold (cold urticaria), deep pressure (delayed pressure urticaria), stress or heat (cholinergic urticaria), sunlight (solar urticaria – p. 1215), water (aquagenic urticaria) or chemicals such as latex (contact urticaria).

Treatment

Any identifiable underlying cause should be treated appropriately. Patients should avoid salicylates and opiates as they can degranulate mast cells. Oral antihistamines (H1 blockers) are the most useful in treating the idiopathic cases. Therapy should be started with regular use of a non-sedating antihistamine (e.g. cetirizine 10 mg daily or loratadine 10 mg daily). If control proves difficult, addition of a sedating antihistamine, an H2 blocker or dapsone may be helpful. Angio-oedema of the mouth and throat may require urgent treatment with intramuscular adrenaline (epinephrine) and intravenous steroids (see Emergency Box 3.1).

Urticarial vasculitis

This is a variant of urticaria and should be suspected if individual urticarial lesions last longer than 24 hours and leave bruising behind after resolution. There is often an associated arthralgia or myalgia, and a small proportion may go on to develop an autoimmune rheumatic disease. The diagnosis is confirmed by skin biopsy. A full vasculitis screen should be carried out for an underlying cause (p. 537).

Treatment is with antihistamines, oral dapsone (50–100 mg daily) or immunosuppressants.

Hereditary angio-oedema

This is a rare autosomal dominant condition due to an inherited deficiency of C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH) which causes massive activation of the complement system, increased bradykinin levels and thus angio-oedema. The defect may be due to either reduced function (type I – 85%) or reduced levels (type II – 15%) and both these are due to mutations in the Serping-1 gene. A low serum C4 level is a good screening test (Table 24.5). Rarely this condition is acquired (due to autoantibody production against C1-INH) and associated with lymphoma or SLE and it presents at a later age. These types show low C1-INH but also low C1q levels.

| Subtype | Gene (inheritance) | Biochemistry |

|---|---|---|

|

Type I |

Serping-1(AD) |

C1-INH low |

|

C1-INH function low |

||

|

C4 low |

||

|

C1q normal |

||

|

Type II |

Serping-1(AD) |

C1-INH normal/raised |

|

C1-INH function low |

||

|

C4 low |

||

|

C1q normal |

||

|

Type III |

Fac XII(XLD) |

C1-INH normal |

|

C1-INH function normal |

||

|

C4 normal |

||

|

Acquired |

Secondary to lymphoma/SLE |

C1-INH low |

|

C4 low |

||

|

C1q low |

AD, autosomal dominant; XLD, X-linked dominant; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

Treatment

FURTHER READING

Le Cleach L, Chosidow O. Lichen planus. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:723–732.

Longhurst H, Cicardi M. Hereditary angio-oedema. Lancet 2012; 379:474–481.

Wuillemin WA. Therapeutic agents for hereditary angioedema. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:84–86.

Neill SM, Lewis FM, Tatnall FM et al. British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of lichen sclerosus 2010. Br J Dermatol 2010; 163:672–682.

Lichen planus

Clinical features

The rash is characterized by small, purple flat-topped, polygonal papules that are intensely pruritic (Fig. 24.19). It is common on the flexors of the wrists and the lower legs but can occur anywhere. There may be a fine lacy white pattern on the surface of lesions (Wickham’s striae). Lesions can fuse into plaques, especially on the lower legs and in black Africans. Hyperpigmentation is common after resolution of lesions, especially in people with pigmented skin. Atrophic, hypertrophic and annular variants can occur. Lichen planus lesions often localize to scratch marks. If lesions occur in the scalp they may cause a scarring alopecia.