Skin cancer – Basal cell carcinoma

Malignant skin tumours are among the most common of all cancers. They are more frequent in light-skinned races, and ultraviolet (UV) radiation seems to be involved in their aetiology. The incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer in caucasoids in the USA was recently estimated at 230 per 100 000 per year, compared with 3 per 100 000 for African Americans. The majority of malignant skin tumours (Table 1) are epidermal in origin and are either basal cell or squamous cell carcinomas (p. 100) or malignant melanomas (p. 103). Premalignant epidermal conditions are common (p. 98), but dermal malignancies are comparatively rare.

Table 1 A classification of malignant skin tumours and premalignant conditions

| Cell origin | Premalignant condition | Malignant tumour |

|---|---|---|

| Keratinocyte | Actinic keratosis (p. 119), in situ squamous cell carcinoma (p. 100) | Basal cell carcinoma Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Melanocyte | Dysplastic naevus (p. 103) | Malignant melanoma (p. 103) |

| Fibroblast | Dermatofibrosarcoma (p. 98) | |

| Lymphocyte | Lymphoma (p. 98) | |

| Endothelium | Kaposi’s sarcoma (p. 56) | |

| Non-cutaneous | Secondary (p. 43) |

Aetiopathogenesis

Clinical presentation

1. Nodular. This is the commonest type of lesion and usually starts as a small, skin-coloured papule that shows fine telangiectasia and a glistening pearly edge (Fig. 2). Central necrosis often occurs and leaves a small ulcer with an adherent crust. The lesions are mostly less than 1 cm in diameter, but grow larger if present for several years. Clinically, they usually present as a thickened plaque rather than a tumour and, although firm to palpation, this may be difficult to establish in smaller lesions. Nodular BCCs often have slightly raised margins with a central depression. Superficial branching telangiectasia are characteristic and are seen on dermoscopy as ‘arborizing’ (Fig. 3). Stretching the skin between two fingers will often accentuate the margins giving them a pale white ‘pearly’ colour.

2. Cystic. These become tense and translucent and show cystic spaces on histology.

3. Multicentric. Superficial tumours, often multiple, plaque-like and several centimetres in diameter, are sometimes seen especially on the trunk (Fig. 4). They have a rim-like edge and are frequently lightly pigmented.

4. Morphoeic. This scarring (cicatricial) variant, most common on the face, often shows a white or yellow morphoea-like plaque that may be centrally depressed (Fig. 5).

Fig. 2 Basal cell carcinoma.

The lesion shows the typical pearly edge, telangiectasia and central crusting.

Fig. 4 Basal cell carcinoma of the superficial multifocal type.

This was located on the trunk. A biopsy (scar visible) confirmed the diagnosis.

Differential diagnosis

Nodular/cystic: intradermal naevus (p. 96), molluscum contagiosum (p. 53), keratoacanthoma (p. 100), squamous cell carcinoma, sebaceous hyperplasia (a benign proliferation of sebaceous glands).

Nodular/cystic: intradermal naevus (p. 96), molluscum contagiosum (p. 53), keratoacanthoma (p. 100), squamous cell carcinoma, sebaceous hyperplasia (a benign proliferation of sebaceous glands).

Multicentric: discoid eczema (p. 38), psoriatic plaque (p. 29), in situ squamous cell carcinoma (p. 100).

Multicentric: discoid eczema (p. 38), psoriatic plaque (p. 29), in situ squamous cell carcinoma (p. 100).

Morphoeic: morphoea (p. 81), scar.

Morphoeic: morphoea (p. 81), scar.

Pigmented: malignant melanoma (p. 103), seborrhoeic wart (p. 94), compound naevus (p. 96).

Pigmented: malignant melanoma (p. 103), seborrhoeic wart (p. 94), compound naevus (p. 96).

Management

The most appropriate treatment for any one tumour depends on its size, site, type and the patient’s age. If possible, complete excision is the best treatment, as this allows a histological check on the adequacy of removal. If excision is difficult or not possible, incisional biopsy (to confirm the diagnosis) and radiotherapy are suitable for those aged 60 years and over. Large tumours around the eye (Fig. 6) and the nasolabial fold, especially if of the morphoeic type, are best managed by surgical excision. Mohs’ micrographic surgery (p. 112) may be employed, as the margins of these tumours are often difficult to determine and may be extensive. Curettage and cautery is sometimes used for lesions on the trunk or upper extremities. Cryosurgery or topical imiquimod (p. 115) are acceptable modalities for multiple, superficial lesions, e.g. on the trunk.

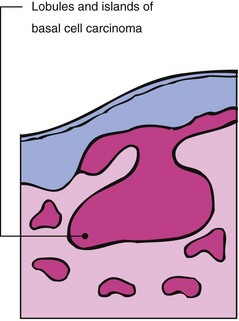

Basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma (rodent ulcer) is a common tumour often seen on the face of elderly or middle-aged patients who may have had excessive sun exposure. It:

Basal cell carcinoma (rodent ulcer) is a common tumour often seen on the face of elderly or middle-aged patients who may have had excessive sun exposure. It:

Basal cell carcinomas with a worse prognosis (high risk) include:

Basal cell carcinomas with a worse prognosis (high risk) include: