8 Skin

Introduction

All children will have a condition affecting their skin at some time. Most conditions are acute and transient, such as the exanthem accompanying acute viral infections like parvovirus, rubella and measles (see Chapter 16). These skin manifestations serve as a useful diagnostic guide but may not require specific treatment. Some, such as atopic eczema, will be chronic and potentially debilitating without appropriate management. Still others will be permanent and require care of the skin lesion and also of potential complications such as the epilepsy seen with port wine haemangioma in Sturge–Weber syndrome (see also Chapter 14, p. 204).

Inflammation

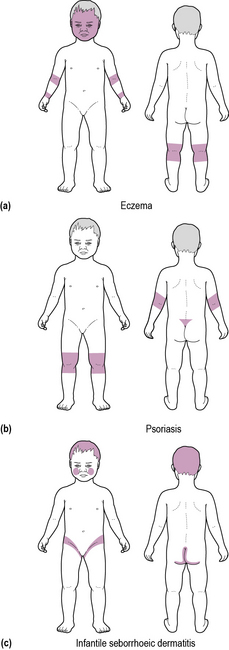

Chronic skin inflammation is usually due to eczema, although more rarely psoriasis is the cause. Self-limiting acute inflammatory disorders are commonly due to allergic or hypersensitivity reactions. The distribution of the rash is often highly characteristic and suggests the diagnosis (Figure 8.1).

Atopic eczema

Eczema is often described as the ‘itch that rashes’. Itch and dryness are key components of atopic eczema. Secondary infection, usually with Staphylococcus aureus and streptococci, is common, and should be suspected whenever the skin is weeping and crusted (as in Case 8.1). Viral superinfection, such as with herpes simplex or varicella, may cause dramatic exacerbations with marked systemic upset – eczema herpeticum.

The ‘itch–scratch cycle’ is a key factor. Dry skin itches and the child scratches. The trauma of scratching releases inflammatory mediators, causing more itch and may also break the epidermal barrier and lead to infection. The distribution of the rash varies with age, the face, head and trunk being more commonly affected in young infants, while the extensor and flexural surfaces of the limbs are more commonly affected in older children. There is a genetic predisposition in many cases with a history of eczema or other atopic diseases in close family members.

Treatment:

• Attempting to reduce the itch by reducing bathing and avoiding biological detergents

• Wearing loose clothing (preferably cotton)

• Managing dryness with emollients, used in place of soap, and applied copiously to affected areas. Wet wraps may help to seal in moisture

• Reducing inflammation by application of topical steroids; use of the more potent creams and lotions should be restricted to short courses to reduce the risk of side-effects

• Calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus) are recommended as second-line treatment by NICE (NICE clinical guideline 57, December 2007). These anti-inflammatory agents are effective, and do not thin the skin, unlike steroids. The commonest side effect is stinging after application, which quickly disappears. They may increase vulnerabililty to infection, and should not be applied to broken or obviously infected skin. There is a theoretical risk that they may increase skin cancer risk, so ideally should not be applied to sun-exposed areas over an extended period, and should not be used in conjunction with ultraviolet light treatment

• Anti-pruritics, usually antihistamines, which may help reduce itch, especially at night when the sedative effect is also potentially beneficial for sleep

• Avoidance of known allergens, which include measures to reduce exposure to house dust mite where appropriate

• Treatment of infection due to bacteria with short courses of oral antibiotics. Long-term use of topical antibiotics in combination with steroids is associated with antibiotic resistance.

• Phototherapy with ultraviolet (UVB) light is beneficial in some cases. Typically, 15–30 treatments are required.

• Severe cases may merit the use of oral steroids, azathioprine or ciclosporin.

Seborrhoeic dermatitis

• Scalp: involvement manifests as scaling and inflammation with the appearance of dandruff, but it may progress to a red, scaly, weeping rash. The rash may extend around the ears and onto the forehead. In infants, scalp involvement has the classical appearance of cradle cap with thick yellow scale.

• Ears: The skin around the ears may ooze and crust, and the ears may swell.

• Face: The nasolabial folds and inner eyebrows are most commonly involved. Eyelid involvement (blepharitis) may be troublesome.

• Chest and back: well-demarcated scaly red patches are seen on the central part of the chest and between the shoulder blades.

• Flexures: flexural involvement affects moist skin folds, particularly the groin, axillae, abdominal flexures and under the breast. Groin involvement is especially striking in infantile seborrhoeic dermatitis.

Psoriasis

Although more common in adults, 25% of individuals affected by psoriasis develop their first lesions in childhood. Around 1–3% of children are affected. Usually it develops as round red raised papules or plaques with a silvery-grey scale. The scalp, elbows, knees, lumbosacral area and the extensor surfaces of limbs are most frequently affected and distribution is often approximately symmetrical (see Figure 8.1). Less commonly seen is the guttate form with multiple small drop-like lesions, which more commonly occurs in adolescents. Associations include nail discoloration and pitting and a form of polyarticular arthritis (see Chapter 6, p. 52). Simple treatment of psoriasis entails adequate use of moisturizers, and sun exposure. Medical therapy is primarily aimed at symptom control. The mainstays of treatment are topical vitamin D analogues (e.g. calcipotriol) and topical coal tar preparations supplemented by short courses of topical corticosteroids. Ultraviolet B treatment (narrowband or broadband) is used in short courses for more severe cases (over the age of 14 years). Second-line treatment consists of disease modifying drugs – methotrexate is used in the first instance; ciclosporin is an alternative, if it is not tolerated. Acitretin, or other vitamin A analogues, may be used in boys, but the teratogenic potential makes use in girls undesirable. Use of second-line agents precludes the use of UV therapy due to the potential risk of skin cancer. Biologic therapy with monoclonal antibodies is reserved for third-line treatment. NICE has approved the following agents: Etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab and ustekinumab for psoriasis.

Skin infections

Bacterial infections

Impetigo

The golden crusts seen in Case 8.2 are typical of impetigo, caused by Staphylococcus aureus or sometimes Streptococcus. The rapid spread is facilitated by auto-innoculation of the infection by rubbing and scratching. Skin swabs should be taken, and ‘best-guess’ systemic antibiotics commenced (e.g. co-amoxiclav) until culture and sensitivity results are available. Recurrence is common, often due to persistent nasal carriage.

Viral infections

Molluscum contagiosum

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by a poxvirus and spreads by auto-innoculation. Uncommonly, secondary infection may occur, causing spreading erythema and tenderness, but more usually the lesions are relatively asymptomatic, as in Case 8.3. Healing, sometimes preceded by an episode of inflammatory change, occurs spontaneously, often after 18 months to 2 years.

Fungal infections

Dermatophytes

Dermatophytes cause a number of superficial fungal infections:

• Scalp ringworm (tinea capitis): well-circumscribed, itchy bald patches, with scaling causing scarring alopecia. Green fluorescence is commonly seen under ultraviolet light, depending on the infecting organism

• Ringworm (tinea corporis): itchy erythematous patches, typically originating in the groin or axillae, extend across the trunk

• Athlete’s foot (tinea pedis): the toe webs are usually affected with moist, white, ‘blotting-paper’ skin. The infection may extend over the sole of the foot, and occasionally, the nails are affected.

Haemangiomas

‘Strawberry’ naevus

The finding of a rapidly swelling telangiectatic lesion early in infancy (as in Case 8.4) suggests a ‘strawberry’ naevus. Strawberry naevi are present in up to 3% of babies and are especially common in preterm infants. The lesion appears at, or shortly after, birth. Lesions grow quickly, reaching a maximum size by 6–12 months of age, after which spontaneous involution begins. Complete resolution usually occurs by age 9–10 years, and there is usually no residual trace – except sometimes a patch of pale or slightly atrophic skin.

Port wine stains

Port wine stains are flat, small-vessel, capillary haemangiomas present at birth. They are often a deep purple shade, and usually flat, but bulky lesions are occasionally seen. They may be quite disfiguring, particularly on the face. When found over the upper cheek and forehead they may be associated with an intracranial vascular malformation – Sturge–Weber syndrome – with epilepsy and learning difficulties (see Chapter 14, p. 204). Early laser therapy is recommended for port-wine stains to achieve the best cosmetic effect.

Alopecia

Alopecia – loss of hair – may be diffuse or patchy.

Patchy hair loss

Alopecia areata

The alopecia areata described in Case 8.5 is the commonest cause of non-scarring alopecia in children. The marginal exclamation-mark hairs, where the base of the hair tapers towards the scalp, and which may easily be pulled out, are characteristic. Nail pitting may be seen. There is an association with autoimmune conditions such as vitiligo and hypothyroidism. The majority of children recover completely, and the value of treatment is uncertain, but where desired, intradermal steroid injection has been used.

Head lice

Treatment:

• Malathion and dimeticone shampoos may be purchased ‘over the counter’. Malathion is ovaricidal and may reduce re-infection

• Isopropyl myristate and cyclomethicone solution

• Coconut, anise, and ylang ylang spray

• Regular wet combing with a fine-toothed comb, preferably after application of a hair conditioner, facilitates removal of nits

• Washing of combs, brushes, bedding, towels and soft toys is usually advised, but of doubtful value.