28 Six questions to ask about assessment

Assessment procedures have been criticised by students, by professional bodies and by those outside medicine. In a recent court case, a judge criticised a nursing school for a failure to identify in its assessment procedures a nurse who proved grossly incompetent and demonstrated unprofessional behaviour after she qualified. For the student, assessment may be seen as analogous to playing in a cricket match where the rules have not been clearly specified in advance and are constantly being changed by the umpire. Students may perceive the examiner as threatening and as someone whose aim is to catch them out and find fault with them (Figs 28.1 and 28.2).

When thinking about assessment it is useful to think about six questions:

1. Who should assess the student?

4. How should the student be assessed?

Who should assess the student?

• international accrediting bodies

• national accrediting bodies such as the General Medical Council in the UK and, in the USA, The National Board of Medical Examiners

• professional bodies, for example the Royal Colleges in the UK and the National Boards in the USA

• the individual school in which the student is enrolled

• the department or course committee responsible for teaching the subject

In medical schools in the UK, the assessment process is overseen by the General Medical Council (GMC) and the implementation is the responsibility of each medical school. Teachers from other schools serve as external examiners and participate in the development of the school’s examinations, their implementation and pass/fail decisions. In contrast, in North America and in some other countries there is a national examination which students are required to pass. Each approach has merits. A national examination, while setting national standards, may stifle innovation in individual medical schools (Harden 2009).

Why assess the student?

The purposes that can be served by assessment include:

• Decisions as to whether the learner is ‘fit for purpose’. Has the learner satisfactorily completed the training programme and achieved the standard expected by the public and professional bodies to practise as a trainee or as a specialist in a particular field of medicine?

• Assessment of the student’s progress during the education or training programme. It is important to identify deficiencies early in a training programme so that these can be remedied without waiting until a final examination when it will be too late to take the necessary action. This is particularly true with regard to the assessment of behaviour and attitudes.

• Grading or ranking the student with the aim of identifying the ‘best’ students among those being assessed. This ‘norm-referenced’ approach to assessment is applicable when candidates have to be selected for a limited number of posts, or students selected for admission to medicine where only a set number of places are available. This approach to assessment should not be confused with a ‘criterion-referenced’ approach where the learner’s achievement is assessed against the expected learning outcomes or a set of criteria.

• Enhancing the student’s learning. Emphasis is placed on ‘assessment for learning’ rather than ‘assessment of learning’. In addition to serving as a tool for accountability, assessment can be a tool to support and improve learning. This is consistent with an ‘assessment-to-a-standard’ approach where what matters are the standards students achieve rather than the time it takes them to do so.

• Motivating the student. It has been demonstrated that assessment has a powerful impact on students and is a major factor in driving their learning. In one medical school we found that, because there was no examination in the subject, students neglected otolaryngology despite the fact that the topic was taught in an imaginative problem-based way. When the subject was routinely included as a station in the final objective structured clinical examination (OSCE), the students’ approach to studying the topic changed dramatically.

• Provision of feedback for the teacher. The teacher can glean useful information from the student assessment but all too often this source of information is untapped. The analysis of students’ scores in one multiple choice question (MCQ) examination revealed that students had performed badly in a question relating to diabetes. This was subsequently found to be related to a weakness in the training programme which had to be addressed.

What should be assessed?

A key feature of outcome-based education, as discussed in Section 2, is that assessment is matched closely with the specified learning outcomes. This is referred to as competency-based assessment. What we choose to assess in the education programme demonstrates what we value and many problems encountered with assessment arise from an inadequate consideration of what is being assessed. Assessment drives learning as we have described above. In the absence of a set of learning outcomes what is assessed becomes, for the students, the course objectives. In the past the emphasis in assessment was on the knowledge domain with less attention paid to skills and attitudes. There were a number of reasons for this. Mastery of knowledge was traditionally regarded as of greater importance than the development of attitudes. Knowledge was also easier to assess than other domains and there was a natural tendency to assess what was easy to assess and to shy away from areas where assessment was contentious or difficult. Written assessments, including MCQ papers which tested the knowledge domain, dominated assessment practice. However, someone who can answer correctly a set of MCQs is not necessarily a good doctor and there has been a move to assess in the student or doctor more complex achievement, higher order thinking, clinical skills, attitudes and professionalism.

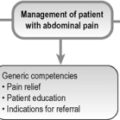

How should the student be assessed?

A wide range of tools or instruments are now available that can be used to assess the student’s competence (Fig. 28.3). Some of these are described in the chapters that follow. Just as important as the assessment tool selected, if not more so, is the way in which the tool is employed. A good tool badly used will yield inappropriate or misleading results. We now have a better understanding of what makes a good assessment:

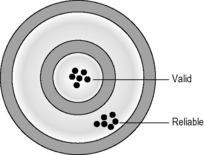

• The method should be reliable and consistent. This relates to the certainty with which a decision can be made about the student’s performance on the basis of the test results. For a reliable assessment the measurement instrument must be relatively stable. It would not be good practice, for example, to use an elastic tape measure to measure length. The measurement would not be reliable.

• The method should be valid. In other words the assessment method should measure the learning outcomes intended (Fig. 28.4). The test should be an ‘honest’ one, testing what it purports to measure. There may be a trade-off at times between reliability and validity. This is illustrated in the classic story of the drunk man who was seen at night looking under a street light for his car keys which he had dropped. When asked why he was looking there when he had dropped them a short distance away, he replied that it was easier to see what was on the ground under the light. His search strategy, although having merit, was not valid in his situation.

• The method should be feasible in terms of the resources available and the number of students to be examined. The assessment scheme should not be overly complex and should be capable of being implemented by the teacher in routine practice.

• The assessment should have a positive impact on the student’s learning. When we first introduced the OSCE in the final examination and included some stations with family physicians as examiners, we found that students spent less time in the library revising their theoretical knowledge and more time learning on the wards and in the community setting. This was in line with the aims of the curriculum.

When should the student be assessed?

Less frequently undertaken is the assessment of the student at the beginning of the training programme. A number of years ago, we asked third-year students at the beginning of their course in endocrinology to complete the end-of-course examination on day one of the course. The results were surprising. Some students scored less than 10% while other students scored almost 50%, the pass mark for the examination. This provided important evidence as to the need for a course in endocrinology which could be tailored to suit the abilities of the different students. Independent learning modules were developed which were used successfully to replace some lectures on the topic. It could be argued that our first student assessment is when we select students to enter medical studies, or select graduates for a postgraduate training programme (see Chapter 32).

Where should the student be assessed?

Students have been assessed traditionally using written papers in an examination hall environment, or with formal clinical examinations in the hospital ward. With moves towards greater authenticity in assessment, and with assessment seen more as a continuous process, increased attention is being focused on assessment in the work place and in the wide range of contexts where teaching takes place, whether in the hospital or community environment. This is discussed further in Chapter 30.

React and reflect

1. Assessment is frequently one of the last things considered when a curriculum is planned. It is often the first thing the learner thinks about. Have you spent enough time considering the assessment of learners in your programme?

2. From the list of purposes given above, what purposes are served by the examinations in your programme?

3. How would you rate your examination against the criteria given for a ‘good assessment’?

Bandaranayake R.C. Setting and Maintaining Standards in Multiple Choice Examinations. AMEE Guide No. 37. Dundee: AMEE, 2010.

Harden R. Five myths and the case against a European or national licensing examination. Med. Teach.. 2009;31:217-220.

Norcini J., Anderson B., Bollela V. Criteria for good assessment: consensus statement and recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 conference. Med. Teach.. 2011;33:206-214.

Norcini J., McKinley D.W. Standard setting. In: Dent J.A., Harden R.M., editors. A Practical Guide for Medical Teachers. London: Elsevier, 2010. (Chapter 41)

Shumway J.M., Harden R.M. The assessment of learning outcomes for the competent and reflective physicians. AMEE Medical Education Guide No. 25. Med. Teach.. 2003;25:569-584.

A description of the assessment tools that can be used to assess the different outcome learning..

Downing S.M., Yudkowsky R., editors. Assessment in Health Professions Education. New York: Routledge, 2009.

A comprehensive text devoted specifically to assessment in the health professions.

Gronlund N.E., Waugh C.K. Assessment of Student Achievement, ninth ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education; 2009.

A classic text worthwhile consulting, particularly Chapter 1.

Hodges B.D., Ginsburg S., Cruess R., et al. Assessment of professionalism: recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 conference. Med. Teach.. 2011;33:354-363.