CHAPTER 8 Simulation Scenarios and Clinical Lessons Learned

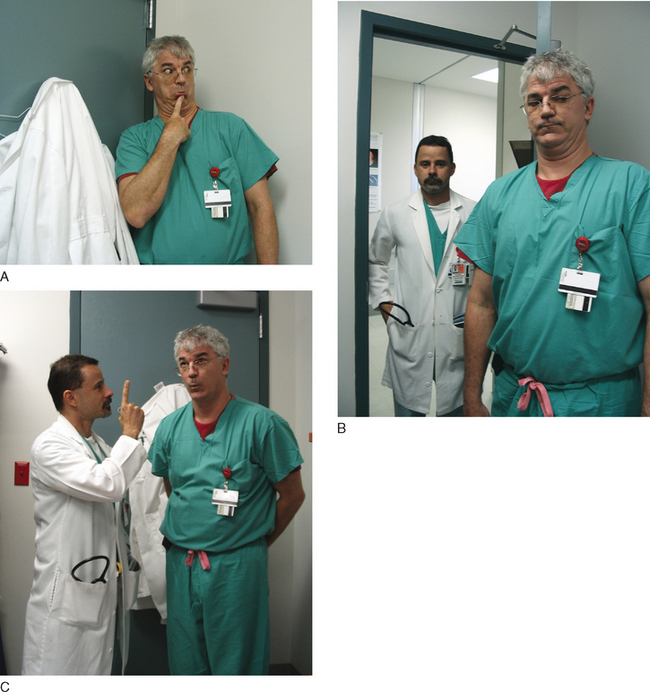

SCENARIO 1. A preop surprise: dealing with a provocative patient

The examining room has a standardized patient (an actor playing the part of a patient).

The resident picks up the chart and looks it over before going in to talk to the patient.

Resident goes into the examining room

“Uh,” the resident stumbles, “OK, um.”

“Aw come on Doc,” the patient says, “don’t be shy.”

“Sweet pea, you can examine me in my briefs any day and twice on Sunday!” the patient says.

“Um.” The resident looks up at the ceiling to see if there are any smoke detectors.

The patient puts a cigarette to her lips, is just about to light up, when the door opens.

“Simulation over!” the Simulator instructor says.

Clinical lessons learned from scenario 1

Here’s how the debriefing goes.

“Well,” the resident admits, “yeah, yes I guess so.”

The resident nods, lips tightened, and face has turned into a “Oh, that ACGME stuff again” mask.

“And is not one of those competencies ‘professionalism’?”

Defeated, the resident’s shoulders slump. “OK, OK, you made your point.”

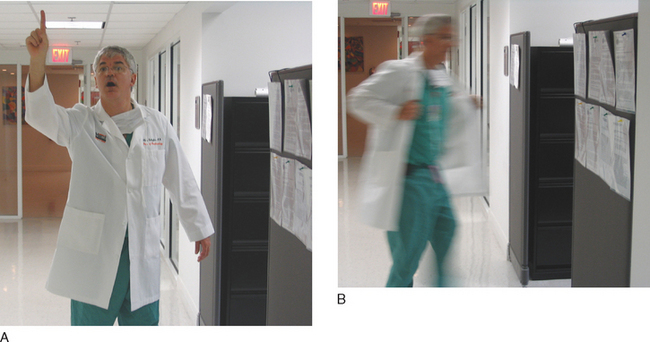

The instructor says, “Pros adapt. That’s the simplest definition of a professional and the best way to teach professionalism. Pros adapt, period.”

“Now here, you have something you never expected. A woman who had you thinking of liver disease and blood counts, and all of a sudden she comes at you from an entirely different direction. What do you do in such a case? What does a pro do?”

“Pros adapt,” the resident says.

Now the resident is all smiles, but a cloud crosses that smiling face.

“Uh,” the resident says, “how, precisely, do I adapt? Um. Sir.”

The instructor is shaking his hand out now, he overdid it on the table, “Thought you’d never ask.”

“What is the crux of the problem you are facing?” the instructor asks.

“What resources do you have in a preoperative setting?” the instructor asks.

“And …” The instructor is letting the resident “find his own way.”

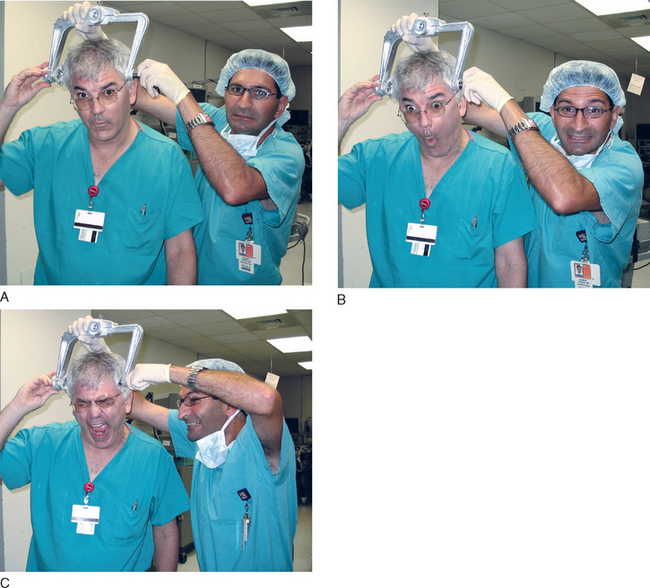

SCENARIO 2. Headache with attitude, an intracranial bleed

“Get to room 3 right away!” The resident goes into the OR.

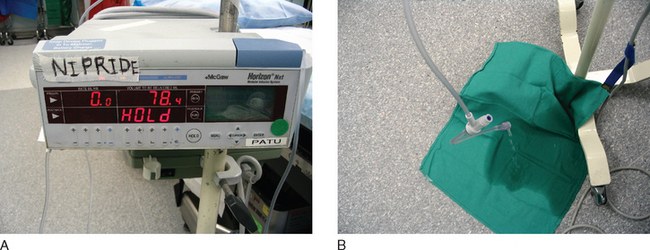

Case. An intubated patient is on the operating table, an arterial line is in, plus a 16 gauge IV. An anesthesiologist is at the foot of the table trying to straighten out the lines. An infusion pump running nitroprusside is on the IV pole, but it came disconnected and is dripping onto the floor. Two surgery people are placing pins on the head, and there is an obvious sense of agitation in the room.

Just as the surgeon says that, the heart rate drops to 100, then 80, then 60, then 40.

Opening the patient’s eyes, the neurosurgeon says, “Hey, look at this.”

After opening the IV wide open to carry in the Pentothol and rocuronium, the anesthesia resident goes up to the head of the bed and looks. The left pupil is blown.

The blood pressure drops down from the stratosphere, now down to 200/120.

Up go the drapes, and the surgeons go at it.

“Hey, this brain is tight as a drum skin, what are you doing up there?”

At the same time, the heart rate increases to 60.

“Simulation over!” the instructor says.

Clinical lessons learned from scenario 2

Haste makes waste, never more so than in a medical emergency.

Let’s look in the mind of this anesthesia resident during the debriefing from this scenario.

Debriefing. The instructor opens the discussion, “What were your priorities in this case?”

“Did you listen to the chest to make sure the endotracheal tube was in?” the instructor asks.

“So why try to get that pressure down?”

“But you didn’t have time to look everything over, did you?”

“The nitroprusside was disconnected, so I couldn’t use that to drop the blood pressure, so I reached for Pentothal to drop the blood pressure and rocuronium to paralyze the patient and prevent further bucking.”

“Would nitroprusside have been your first line to drop the blood pressure?” the instructor asks.

“What did you think about the head positioning?” the instructor asks.

“When troubles come, they come not as single spies,” the instructor says, “but in battalions.”

“Amen to that,” the resident says.

“And once the head was opened, what was the next problem that appeared?”

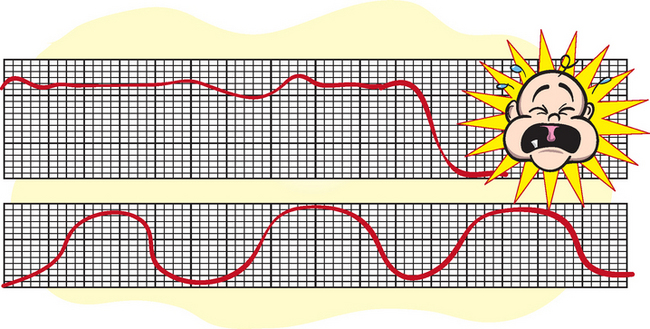

“But the CO2 got away from you,” the instructor observes.

“But not too much, right?” the instructor asks.

“These neuro cases are real physiologic showcases, aren’t they?”

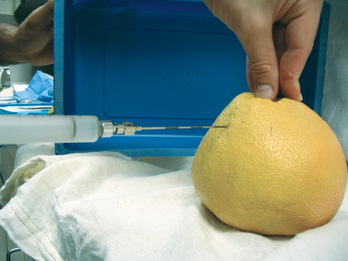

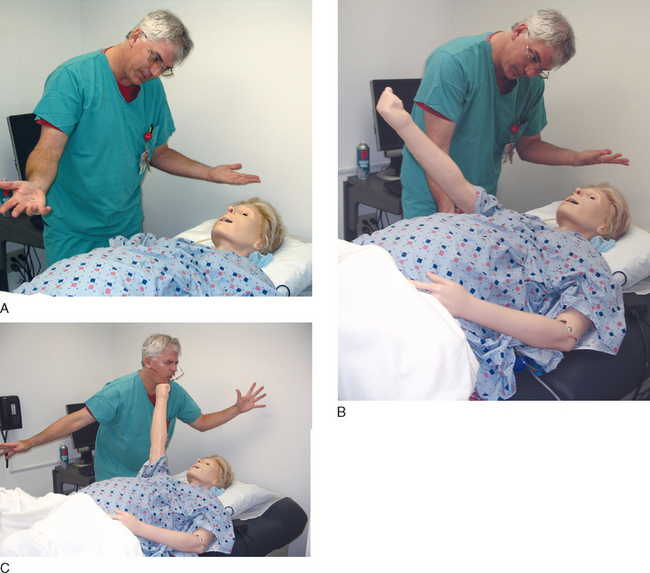

SCENARIO 3. Local in the wrong locale, intravascular injection during an epidural

“Bozhe moi,” the patient groans, “bozhe moi, boleet, boleet! Rebyonik vilyezaet!”

The patient is connected to a blood pressure cuff, a fetal heart rate monitor, and a pulse oximeter.

Lost in the paperwork, the anesthesia resident says, “Uh huh.”

The anesthesia preop outlines the case.

The anesthetic record detailed an unremarkable course.

“Good pain relief, patient stable, FHR OK throughout.”

But now the OB was complaining, in English, and the patient was complaining, in Russian.

“OK, is the husband around?” the resident asks, “my Russian is not too good.”

“Um, OK,” the anesthesia resident says, “my name is Dr. Nelson, not ‘honey’.”

“Bozhe moi, pomogeetye mnyeh, rebyonik vilyezaet, rebyonik vilyezaet!” the patient shouts.

“Boleet, boleet! Akh da, gdye moi moozh?” the patient shouts.

“No need,” Dr. Nelson says, “the epidural became disconnected, I’ll have to rebolus.”

“Oh great,” the OB says, “well make it snappy, I’ve got to get these salad spoons on.”

The fetal heart rate monitor drops to 40, the patient’s pulse oximeter stops beeping.

“Hey!” the OB shouts, what’s going on here? What did you give?”

Dr. Nelson looks around for a laryngoscope, an Ambu-bag, anything.

“Simulation over!” the instructor chirps.

Clinical lessons learned from scenario 3

Dr. Nelson faced a prickly path in labor room 2.

And that was just the start of Dr. Nelson’s troubles.

The debriefing picks up the thread.

Debriefing. “So,” the instructor says, “how do you think that went?”

“Relax,” the instructor reassures, “be glad she didn’t have twins. Then it would be 300%.”

“Thanks,” Dr. Nelson groans, “I feel a lot better.”

“No,” Dr. Nelson says, “there is the human factor.”

“Aah yes,” the instructor agrees, “and what are the human factors at work here?”

“Well,” Dr. Nelson starts out, “the OB was a demanding asshole of a chauvinistic pig.”

The instructor says, “Touché, you did that. What was the other human factor going on here?”

“What do the textbooks say about that?” the instructor asks.

“Yep,” Dr. Nelson admits, then turns to the Russian technician, “What were you saying, anyway?”

“Turns out I was saying something important,” the technician says, in perfectly unaccented English, “I was saying, ‘It hurts, the baby is coming.’ The whole controversy here swirled around dosing me up for a forceps delivery. But while you and the OB were sniping at each other, the baby was coming down on his own, obviating the need for forceps and for the dose-up.”

“Why do you say that?” the Russian speaker asks.

“Did you have any of that stuff?” the instructor asks.

“I don’t follow you,” Dr. Nelson admits.

“How effective are chest compressions in the still-pregnant patient?”

“Righty-oh,” the instructor wraps it up.

Maybe next time they should do that “knife cuts the pain in half” trick from Gone with the Wind.

SCENARIO 4. Help from across the drapes, hypoxemia in the OR

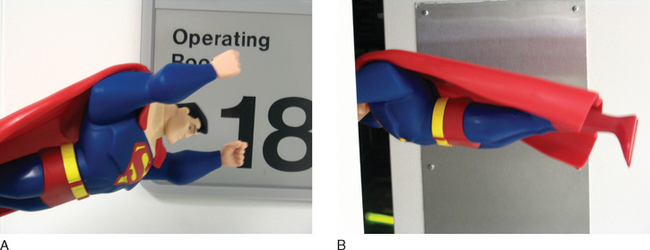

“Any anesthesiologist to OR 18, any anesthesiologist to OR 18 stat!”

A CA-3, a senior anesthesia resident, answers the call and goes into OR 18.

In OR 18, a CA-1, a junior resident, is at the head of the table, hand ventilating the patient. The patient is intubated, the drapes are up, and everyone is in mid-operation, two surgeons operating and the usual surgical team doing their thing.

“What’s up?” the senior resident asks.

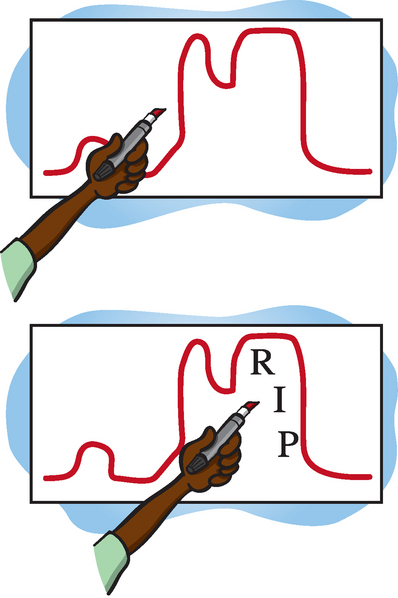

On the EKG, a tombstone pattern of ST elevation is present. Ischemia that a blind man could see.

The CA-3 looks over the vital signs, oxygen saturation 100%, BP by cuff 85/50, pulse 130.

“Why are you hand-ventilating?” the senior asks.

“Now why’s this guy ischemic?” the senior asks.

An audio alarm goes off, both reach up to silence the alarm.

Another audio alarm goes off. Again, both reach to silence the bothersome alarm.

Two alarms now go off, and both get silenced in a split second.

“I’m not kidding you guys,” the second surgeon says, “this blood really does look dark!”

“Yeah yeah,” the CA-3 says, “sure it does. We got it.”

On the EKG, the STs are even higher.

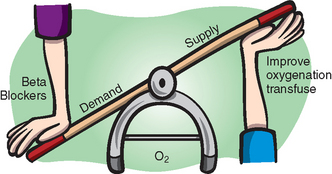

“Listen, this is all about myocardial supply and demand, and right now there’s too much demand—look at that heart rate—and not enough supply—look at that blood pressure,” the senior explains. “Hang blood, keep transfusing until that heart rate goes down. They’ve obviously lost a ton resecting that liver.”

“Hey,” the CA-3 is bristling with territoriality, “what are you doing….”

A look of triumph on his face, the surgeon goes back to the other side of the curtain.

“We’re done!” the instructor says.

Clinical lessons learned from scenario 4

But call it you must, if in trouble. And respond you must, if you hear it.

Presto-chango, ischemia prone myocardium is now ischemic myocardium.

Never fear, senior resident to the rescue!

The debriefing reveals just how good a rescue he delivered.

Debriefing. “What were you thinking when you called for help?” the instructor asks the CA-1.

“Did you think you would need an a-line for this case?” the instructor asks.

“Boy howdy, he did,” the junior says.

“Not too well, they were bugging me, mostly, and not much help,” the junior says.

“Does that matter?” the instructor asks.

“No need for martyrs here,” the instructor reassures, “just go through what you were thinking.”

“So what did you do?” the instructor asks.

“Why did that happen?” the surgeon asks in, of all things, a reasonable tone.

“Sorry,” the CA-3 apologizes. “So anyway all this stuff is going on, and alarms are going off, which I stupidly shut off rather than paying attention to.”

SCENARIO 5. Too much of a good thing—narcotic overdose

“Doctor, could you step over here,” the ICU nurse says, “there’s something you need to see here.”

The resident looks over the chart, it’s all there, just like the ICU nurse said.

“Is this guy on PCA narcotics?” the resident asks.

“Yes,” the nurse answers, “but we haven’t changed the dose or lockout interval.”

“Yes, he’s on subq heparin, all the usual DVT prophylaxis,” the nurse reports.

“Do you think we should intubate doctor?” the nurse asks.

“Um, let’s get an ABG first, and get suction up here in case he vomits.”

With more shoulder shaking, the patient arouses a little more, “Hey, sir what gives?”

“Good s***,” the patient says, then goes back to sleep.

“Let’s get a CXR,” the resident says, “maybe the pneumothorax came back or something.”

“ABG results,” the nurse says.

Now the patient is opening his eyes a little more, taking more frequent breaths, and his sat is coming up a little.

On the view box, the repeat CXR goes up—nothing abnormal, no reaccumulation of pneumothorax.

“Simulation over!” the instructor says.

Clinical lessons learned from scenario 5

So she calls in Dr. Sherlock Holmes to unravel the mystery.

Debriefing. “What were your concerns when you entered the ICU?” the instructor asks.

“Was he moving air, was he protecting his airway?” the instructor asks.

“So were you thinking narcotics?” the nurse asks.

“Did you look at his eyes to see if he were miotic?” the instructor asks.

“So where did you go from there?”

“Then why not intubate?” the instructor asks. “Wouldn’t you do that in the trauma bay if someone were not protecting their airway, if they were barely responsive? That’s, what a Glasgow coma scale of 8 or so?”

“And it turned out OK, didn’t it?” the instructor asks.

Here, the videotape of the scenario is played, and the instructor stops at a few crucial spots.

“Put it together for me, doctor,” the instructor says.

Summary. “There are none so blind as those who will not see.”

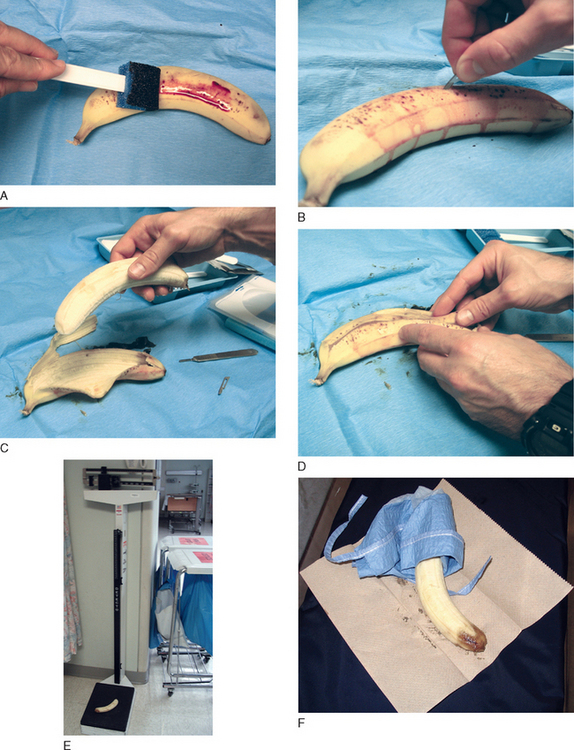

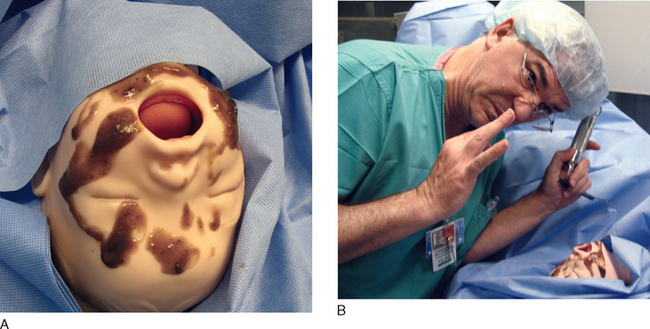

SCENARIO 6. Bad beginnings, inducing with an infiltrated IV

The arterial trace shows a narrow upstroke, and a blood pressure of 170/90. The heart rate is 80.

No response from the patient. His eyes are closed.

The blood pressure is still up there, 170/80. The heart rate is creeping up there, 100 now.

Dr. Kettle comes through the door of the OR.

“What the hell is that?” Kettle asks, pointing to the endotracheal tube.

“Uh, the endotracheal tube,” the fellow says.

“Well, well …” the fellow stutters.

“You stick a central line in these patients. This is not some lap choly in an aerobics instructor! This patient is death waiting to happen. If you can’t get the line, which I suspect might be the case, then god damn it, you page me and I’ll put it in for you!” Kettle has a way with words.

“Simulation over!” the instructor chirps.

Clinical lessons learned from scenario 6

The debriefing rolls out the tale for our delectation and instruction.

Debriefing. “Were you ready to roll on that induction?” the instructor asks.

“So you have to be delicate, oh so delicate when you induce these patients.”

He achieved sufficient anesthetic depth, controlled heart rate and blood pressure, responded appropriately to threatening ST changes, and secured the airway.

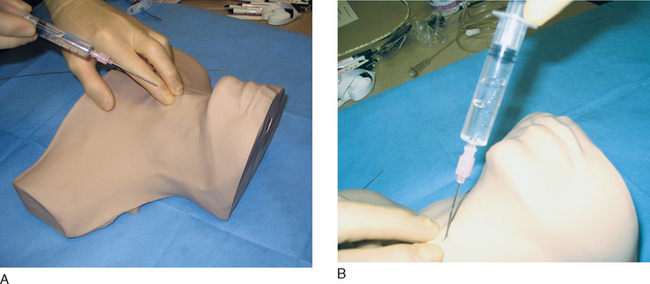

SCENARIO 7. Needle phobia and placenta previa

“Have you …” the anesthesia resident starts.

The OB and the anesthesia resident step out into the hall for a moment.

“Thanks,” the anesthesia resident says, “is it shift change? Can I crawl out a window or something?”

“What’s not, that’s a shorter list.”

“I’ll need some monster IV access” the anesthesia resident says.

“Here’s the scoop, this will be ugly, but here it is,” the anesthesia resident says. “I’ve got a pregnant woman, full stomach, refusing lines, bad IV access due to IVDA, and I’ll be needing big time access in case she bleeds like no tomorrow. I’m going to have to sedate her enough to get a line in, and the road will go one of two ways here—either I can sedate her enough to get a real central line in, a big hogger, and then we’ll be ready to go. Or else I can sedate her enough—this will have to be IM, hate to say—to just get a teeny but ‘OK to induce general anesthesia but not to start cutting with’ IV.

“Simulation’s over!” the instructor says.

“But … but I haven’t done anything yet!” the anesthesia resident protests.

Clinical lessons learned from scenario 7

All this emerges during the debriefing.

Debriefing. “How do you think that went?” the instructor asks.

“And I didn’t, really, do anything!”

“Keep your pants up on the OB floor, please,” the OB resident says.

Everyone cracks up on that one.

“So lay it out for me,” the instructor says, “what went into the plan A and plan B you had?”

“Third, think of the specific problems associated with this pregnancy versus just any old pregnancy—placenta previa, big time blood loss. And I have to be ready for that with lines and cross-matched blood.”

“Of course you do,” the anesthesia resident says, “but that’s where you show your professionalism.”

Going on, the anesthesia resident says, “The fact is, this is the way this woman is. From the IV drug use, from her upbringing, who knows. It’s not for me to unravel and it’s not for me to undo, but it is for me to deal with. So from a ‘I need you to cooperate’ there is only so much I can do. Yes, I will talk to her; yes, I will tell her how much better it would be if she would hold still; and yes, you can do a previa with an epidural anesthetic (controversial because in the face of massive hemorrhage you would miss her sympathetic tone). But if she just plain does not cooperate, then she just plain does not cooperate. She is no more capable of cooperating than a patient with congenital or acquired ‘cerebral insufficiency.’

“Same applies here,” the anesthesia resident says.

Summary. This anesthesia resident walked into a real minefield.

And planning ahead is half the battle.

Whew, glad this difficult scenario is over. All three residents can now rest easy.

SCENARIO 8. No IV access in a difficult, bleeding patient

“Um,” the OB resident says, “things might be getting worse here. I don’t think time is on our side.”

“We’re bleeding bad down here,” the OB resident says, “real bad.”

“Quiet in here,” the anesthesia resident says.

After 30 seconds, the resident puts the laryngoscope in the mouth, lifts, and sees nothing.

“What’s up?” the OB resident asks.

“No view,” the anesthesia resident says, taut as a piano wire.

She picks up another blade, repositions the head.

“Sustained bradycardia!” the OB nurse shouts. “Forty, I’m not kidding, 40!”

“Listen, I gotta get this kid out, I gotta get this kid out,” the OB says; he, too, strung up tight.

“Nothing,” the anesthesia resident says. Behind her, the saturation drops into the 80s, the 70s. The nurse holding the cricoid pressure keeps looking back at the fetal heart rate monitor, and her hand pulls up from the throat.

Another resident walks in the room.

“O’Reilly from surgery, what can I do for you?” he says.

In the surgical field, the OB pulls out a baby, hands it to peds.

“Thick meconium,” the OB says.

“Got it!” the peds resident takes the baby away in a towel. In the bassinette, he suctions the mouth, intubates, suctions the endotracheal tube, removes it, then mask-ventilates. The baby, originally blue (via LCD displays in its face), pinks up.

The door opens, “That’s all folks!”, the instructor says.

Clinical lessons learned from scenario 8

OB adds, “Communication, making sure you ‘close the loop’ when you talk to people.”

“That’s not an official CRM thing,” the instructor says, “but maybe it should be.”

“That’s right,” the instructor says. “It’s no crime to say the things we do right in a Simulation scenario. There is a tendency to flog ourselves and just dwell on the stuff we do wrong. It is well and good to see the wrong stuff and correct it, but it’s just as important to see the good stuff and make sure you keep doing that good stuff.”

“What do you think was causing the hypotension?” the instructor asks.

“Bleeding,” the anesthesia resident says.

“Bleeding,” the OB nurse says, and the peds resident and the O’Reilly factor agree.

“Could it have been a pneumothorax?” the instructor asks.

“Oooooooooooh,” peds and O’Reilly say.

“Touché”, the instructor says, “she didn’t. But still….”

“True,” the instructor says, “so take us through your thinking.”

“But you were able to ventilate,” the OB resident says.

“Let’s go over the peds resuscitation,” the instructor says. “Meconium means what?”

“Damn,” O’Reilly says, “you’re good, you could do this for a living.”

“So anyway, the thing to do is fight the urge to mask-ventilate the kid right away,” the peds resident says. “It is so tempting to just ‘mask him up a little’; and I’ll tell you, I’ve seen some anesthesia people succumb to that temptation.”

Blushing, the anesthesia resident conceded the point without saying a word.

“It’s a battle of nerves, isn’t it?” the instructor asks.

“That it is,” the peds resident says.

“But you have to wait,” the instructor says.

“Can’t end on a better note than that,” the instructor concludes.

The anesthesia resident could have paused to get all “legal eagle” about consent for a central line, but at a certain point you have to be a doctor and not a lawyer. She did the best she could, first explaining, then sedating, and then getting the line. Absent the line, the patient would bleed to death, and that the anesthesia resident was not willing to do, no matter how the brother-in-law would react.

SCENARIO 9. Mediastinal mass

The patient is lying flat on the OR table, and the anesthesia resident is reading the preop.

“Oh sure,” the anesthesia resident says, putting the bed in reverse Trendelenburg. “That help?”

“A little,” the patient has a gasping sound in his voice.

The surgeon taps his watch, “Tempus fugit” (Time flies—Latin).

“Right, right,” the anesthesia resident says, “well, looks like we’re ready.”

“Unless you have something else you’d rather be doing?” the surgeon snipes.

Reaching behind him, the anesthesia resident turns on the sevoflurane.

“What? You already have a big line!” the surgeon protests.

“We got the gurney nearby, right?” the anesthesia resident asks the OR nurse.

“Sure, why?” the OR nurse asks. This isn’t a prone case.

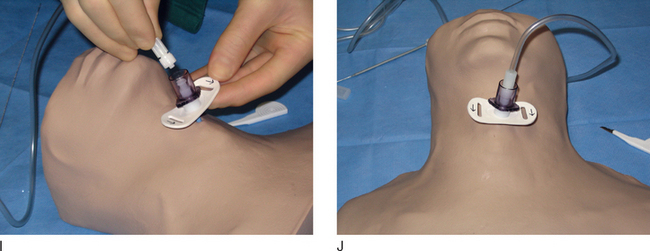

“And do you have a rigid bronch in the room?” the anesthesia resident asks.

The room is charged with two doctors calling each other doctor.

“Femoral line’s in,” the instructor says.

The drapes go up and the surgery starts, “He’s bucking, better paralyze him,” the surgeon says.

“You ready to go on fem-fem bypass if I need it?” the anesthesia resident asks.

“Simulation over,” the instructor says over the loudspeaker.

Clinical lessons learned from scenario 9

The surgeon functioned that way in this case, much as Dr. Kettle did in the aortic valve scenario.

Debriefing. “What were your red flags in this case?” the instructor asks.

“There was clinical and lab evidence of big time obstruction with this mass,” the anesthesia resident explains. “He was short of breath lying flat, that’s not good, and the flow volume loops showed obstruction; so, again, you are seeing signs that this mass is a real problem.

“Any other options before you induce—any medical options?” the instructor asks.

“I’m not picking up your thread here,” the anesthesia resident says.

“Treat before they see the meat?” the OR nurse asks.

“Why didn’t you induce like they usually do?” the OR nurse asks.

“And the other things?” the instructor asks.

“And the rigid bronch?” the instructor continues. “The femoral line?”

SCENARIO 10. No smooth sailing, triage after a disaster

“A what?” the anesthesia resident asks.

The gasping patient has a saturation of 85% and a heart rate of 140.

The silent patient has a saturation of 0 and a heart rate of 0. Flat line, asystole.

“Are we it?” the resident says, “we’re going to….”

The gasping is getting more high-pitched, the saturation is down to 80%.

“Anyone here who can cut a neck if I can’t intubate this guy?” the anesthesia resident says, “He may be all burnt up in the airway, swollen up.”

“All the surgeons are in the other trauma bays, you’re it.”

“No,” the nurse says, “no one to take them, no one to read them.”

“What’s that?” the anesthesia resident asks, pointing at the long skinny thing.

“How the hell should I know? They never let us intubate,” the ER nurse says.

Suddenly, the high-pitched gasping stops with one final squeak and the saturation starts to plummet.

“Gimme the cric kit,” the anesthesia resident says.

“You don’t want to try the Shikani?” the ER nurse asks.

“We better sedate this guy and sandbag his head, we don’t have the collar on anymore,” the resident says. “You happen to have an insufflator here, I’d like to insufflate air through this little opening.”

“What’s an insufflator?” the ER nurse asks, looking around.

“Simulation’s done folks!” the instructor says.

Clinical lessons learned from scenario 10

Debriefing. “Can you spell T-R-I-A-G-E?” the instructor asks.

“I can sure spell it better than I can spell ‘Shikani,’” the anesthesia resident quips.

“What were you thinking when you first got this news in the hallway?” the instructor asks.

“But before you even got there, you had to make another decision,” the instructor says.

They review the DVD of his quick exam on the asystolic patient.

“So hey, what do I do, expend a lot of energy on a rhythm that rarely comes back anyway? Asystole is the baddest of the bad. I mean, come on, King Tut, technically, is in asystole. You going to spend a lot of time resuscitating him?”

“No way I’m doing mouth to mouth on a mummy!” the ER nurse says.

“No regrets on that decision?” the instructor asks.

“Hard times require hard decisions,” the anesthesia resident says, “so, no. No regrets.”

“OK, let’s go to the airway,” the instructor says, “what are you thinking there?”

“Why not use the Shikani system,” the ER nurse says, “it’s made for just this kind of thing.”

On the DVD, the resident does a slick job getting in the cricothyrotomy.

“Why not a regular trach?” the ER nurse asks.

“Only this central line actually is central!”

“But you didn’t do insufflation through it,” the instructor says.

“What would your next moves be?” the instructor asks.

“But I’m sure you would have,” the instructor prompts.

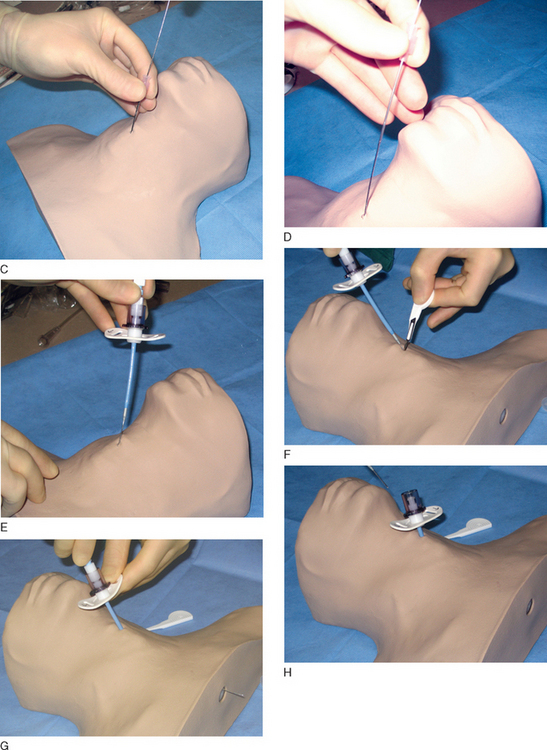

Anesthesia residents tend to live in morbid fear of that awful time when they have to “take up the knife” to secure the airway. Current airway kits take the terror out of this procedure so long as you make that one little intellectual leap.

I’m just putting a central line in the trachea.

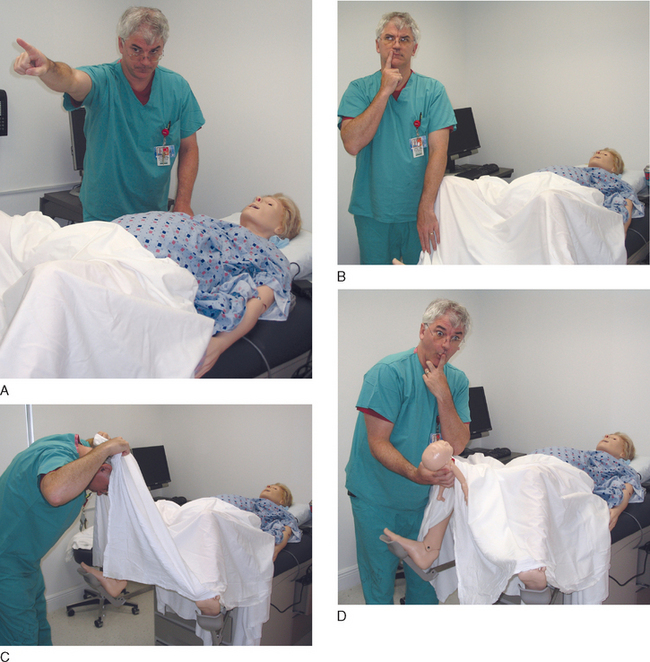

SCENARIO 11. The miracle of birth, stat C-section

The OB nurse grabs the anesthesia resident by the sleeve, “Time for the MOB.”

“Miracle of birth,” the nurse explains.

“STAT C-section!” the OB shouts, then turns around and runs out.

“Anything we can do to buy some time doctor?” the OB nurse asks.

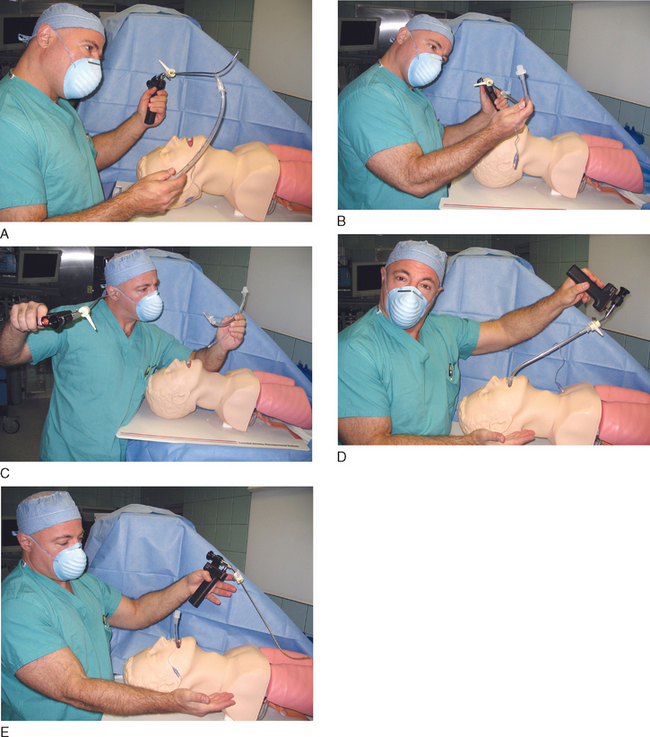

The scenario does a technical time out, as the team goes from the labor suite to the OR suite.

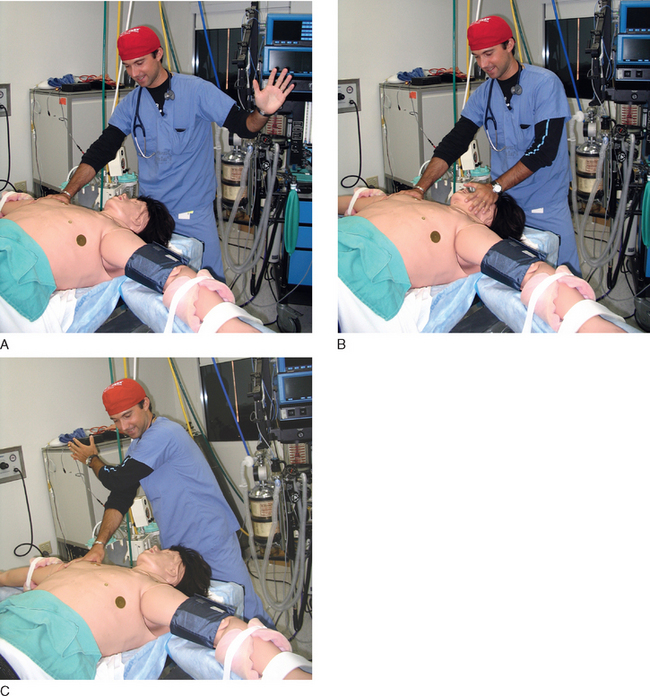

In the OR suite, the patient is being preoxygenated. The patient is flat on her back.

“Suction!” the anesthesia resident shouts, looking around. Damn, where is the suction—oh, here.

“Um, I need someone up here,” the resident says, “right now.”

“Heart rate 50, come on!” the OB is apoplectic.

“Oh shit!” the anesthesia resident says.

“Oh shit!” the OB resident says.

“My arm hurts!” the patient yells. “I feel weak.”

Looking down, the anesthesia resident sees that the IV site is red and infiltrated.

“I … can’t … breathe,” the patient’s voice falls off. “My … arm …” then she falls silent.

Behind the anesthesia resident, the blood pressure cuff alarms, error—error—low BP reading.

The OB resident looks up, “You didn’t put her to sleep, did you? She’ll need to push now.”

His hair attempting to stand on end through his OR cap, the anesthesia resident says in a voice an octave higher than usual, “I could use a hand.”

The circulator comes out from under the drapes, goes to the head of the bed, and gives cricoid.

The pulse oximeter comes back.

“It’s a wrap! Simulation’s done!”

Clinical lessons learned from scenario 11

Debriefing. “Some miracle of birth,” the instructor says.

“Call it the ‘madness of birth,’” the first anesthesia resident retorts.

That loosens up the whole debriefing table.

“What happened in between point A and point B?” the instructor asks.

Starting out, the OB nurse says, “We got a real bad deceleration, and we had to get going.”

“God is sending you an urgent e-mail,” the instructor says.

“And what do you do when you see this red flag?” the instructor asks the anesthesia resident.

“OK,” the instructor says, “let’s put that on the time line.”

“So,” the instructor continues, “what is a good antidote to panic?”

“Go back to ABC,” the first anesthesia resident says, “and call for help.”

“What’s the big deal about help?” the OB nurse asks.

Rolling her eyes, the OB resident says, “Gotta always take a peak between the legs and see if Baby Dumpling has made a surprise arrival. In my rush to cut, I forgot an important lesson of delivery—kids have their own agenda and sometimes deliver from below while we’re going at them from above.”

“Sort of a Grand Slam of trouble,” the instructor offers.

“Then I arrived to save the day!” the second anesthesia resident trumpets.

“Your day will come,” the OB pokes a hole in the resident’s balloon.

“You could argue different options,” the OB says.

SCENARIO 12. Keeping an eye out, agitation in an opththalmic case

The resident shrugs, “Whatever, so long as you sign the check at the end of the month.”

“Figaro, Figaro, Figaro, Figaro!”

God, how can people listen to this stuff.

“Oh, yeah,” the anesthesia resident looks around, there’s some Versed.

The anesthesia resident gives 1 mg of Versed, waits a minute or two, then gives 1 mg more.

“Figaro la! Figaro cua! Figaro la! Figaro cua! Figaro, Figaro, Figaro, Figaro!”