25 Simulation of the clinical experience

Reasons for simulation

• ‘Real patients’ may not always be available for clinical teaching. With changes in healthcare delivery patients’ stay in hospital is now shorter and during their stay they are occupied with investigation and treatment procedures. Patients may be less willing to have repeated exposure to students.

• With simulation every student can receive a guaranteed and standard clinical experience. Unlike with real patients a simulated experience can be made available to students at the most appropriate time to fit in with their learning programme.

• Repetitive practice is recognised as a key element in the acquisition of clinical skills. Learners can practise with the simulator until they have achieved the necessary mastery of the skill.

• Students are now introduced to clinical experiences earlier in many curricula and preparation on simulated patients and simulators can prepare them for their work with real patients.

• Trainees can be exposed to uncommon situations or rare clinical events that they may not encounter in their routine clinical experience.

• The management of crisis events can be practised and rehearsed so that students and trainees are better prepared should such events occur in real life. Airline pilots are trained in this way and simulators enable the pilots to deal with extreme situations such as engine failures.

• Students can learn a procedure in a risk-free environment. Learners can make mistakes and appreciate their consequences without causing harm to patients. Indeed in some areas it is now a requirement that a doctor demonstrates mastery of a procedure on a simulator before being approved to perform it on a patient. Uncoupling injury from learning sends a message to the public that patients are not ‘a commodity’ for training.

• Doctors need to be able to work as a member of a team. Simulation can address not only the acquisition of individual technical skills but also be used to train the learner to work in a coordinated and effective manner as a member of a team.

• The assessment of a learner’s mastery of a clinical skill is important. Simulated patients and simulators can be used for this purpose in examinations, including high stakes examinations, to assess the learner’s mastery of a skill as described in Section 5.

• Simulation can be used to provide students with a motivating and engaging learning experience. This can be designed to challenge the students, encourage their reflection and provide feedback about their performance. The experience can be customised to meet the needs of the individual learner.

Approaches to simulation

There are three approaches to simulating the real patient:

1. Simulated patients. These are individuals trained to play the role of a patient.

2. Simulators or manikins. These are devices or models that represent the functioning of the body or part of the body and with which the student can interact.

3. Virtual patients. The patient is represented in a computer simulation.

Choice of simulation

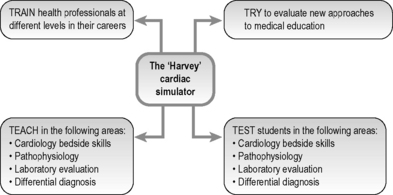

• The expected learning outcomes. Simulated patients are the obvious choice if communication skills are the expected learning outcome. Computer-based programmes designed for the purpose also have a role to play in communication skills training. If skills in auscultation are the required learning outcome, a manikin such as the Harvey cardiac simulator is appropriate. Virtual patients can contribute to decision-making, problem-solving and patient-management skills.

• The level of fidelity required. Simulators vary in how similar they are to the real situation they are designed to simulate. A high fidelity simulator may be unnecessarily complex and expensive, and a simple piece of plastic simulating a wound on the skin may be adequate to teach suturing skills. A higher fidelity simulator may be required in a high stakes examination but may not always be necessary in a training situation. However, students tend to be more engaged with a high fidelity simulation that more closely resembles a patient.

• The availability of simulators. This may be a limiting factor. If students do not have immediate access to a clinical skills centre with a full range of simulators, it may be possible to arrange access to a nearby centre. If a bank of simulated patients is not available, a simulated patient can be trained to meet the needs of a programme but this can be time consuming. Virtual patients that can be shared online across institutions and modified to suit a local context are now available.

Simulated patients

• teaching and assessing history-taking and communication skills

• providing the student with the experience of counselling a patient in a difficult or sensitive area such as cancer where the use of a real patient would be inappropriate

• teaching and assessing physical examination

• teaching and assessing intimate examination of the genitalia.

Barrows (1993) and others have described how simulated patients can mimic a wide range of physical findings from an acute abdomen to spasticity. Simulated patients can be trained to portray various levels of difficulty appropriate to the stage of the learner. The simulated patient may provide a simple account of his or her history on being questioned by the learner or the patient can be programmed to be aggressive and difficult with a confusing or muddled history. Simulated patients can be trained to represent different settings of care including ambulatory care and general practice. A special group of simulated patients are recruited specifically to provide students with opportunities to learn the skills of male and female genital and digital rectal examination and female breast examination.

Simulators (manikins and models)

Over the last two decades, manikins or models have been increasingly used to simulate ‘real’ patients in the teaching of clinical and practical skills and are now part of mainstream medical education. Simulators enable learners to practise patient care in a controlled and safe environment. The level of the sophistication of the manikins and models varies. At one end of the spectrum, simple models can be used that allow students to practise their skills in breast examination, prostate examination, wound closure, catheterisation, injection techniques and many other techniques and procedures. At the other end of the spectrum there are sophisticated models such as ‘Harvey’ – a life-sized cardiovascular patient simulator that can depict the auscultatory, tactile and visual findings for a broad range of cardiac problems (Fig. 25.1).

There is good evidence that the skills gained from practice on a simulator transfer to real patients. Issenberg et al (2005) in a systematic review of the use of simulators identified key features that contribute to their educational effectiveness:

• Provision of feedback. Not surprisingly this was identified as an important feature of simulation-based medical education. (Feedback, the ‘F’ in ‘FAIR’, was discussed in Chapter 2.)

• Repetitive practice. Simulators provide an opportunity for learners to engage in deliberate practice where the learner engages in focused and repeated practice with the learning outcomes clearly defined. (Activity, the ‘A’ in ‘FAIR’.)

• Curriculum integration. Simulation-based learning is most effective when it is embedded in the curriculum and not seen as some extraordinary event.

• Range of difficulty level. Effective learning is enhanced when learners have opportunities to engage in the practice of medical skills across a wide range of difficulty levels. (Individualisation, the ‘I’ in ‘FAIR’.)

• Capture of clinical variations. The representation of a wide variety of problems or conditions as related to clinical practice. (Relevance, the ‘R’ in ‘FAIR’.)

• A non-threatening environment. The use of simulators is most valuable where mistakes by learners are expected and not criticised, and where these are regarded as ‘teachable moments’.

• Individualised learning. The learning on the simulator should be adapted to individual learning needs. This may mean that some students will require longer and more practice on the simulator than others. The level of difficulty of the presentation on the simulator may be altered to match the needs of the student. (Individualisation, the ‘I’ in ‘FAIR’.)

• Defined outcomes. The expected learning outcomes for using the simulator should be defined and related to the overall outcomes of the curriculum. (Relevance, the ‘R’ in FAIR.)

Computer simulations and virtual patients

1. information about the patient including history, physical findings, laboratory and other investigations and the patient’s progress

Advantages of virtual patients

• Virtual patients can be used to provide students with a wider range of patient scenarios than they may encounter in the real situation.

• The learner can take on the role of the doctor and no harm can result from any mistakes made.

• A holistic approach to patient management can be encouraged. The learner can interact with the patient and engage in reflection and clinical reasoning, while at the same time recognising professional and ethical issues.

• The virtual patient can highlight the integration of theory and practice, and the basic sciences with clinical medicine.

• Virtual patients can be used for teaching and learning and for assessing learners with the learners receiving feedback.

• Virtual patients can demonstrate the continuity of care with the same patient located over time in different contexts including general practice and the hospital setting.

Uses of virtual patients

Virtual patients can be used in a number of ways, for example:

• to support a traditional curriculum or learning programme, complementing the lecture and clinical experiences

• as the triggers or problem presentation in a problem-based learning curriculum (see Chapter 14)

• to support independent learning with students individually working through the case scenarios

• in collaborative learning with students working through a virtual patient scenario in pairs or in a group.

Reflect and react

1. Simulation is a powerful teaching and learning tool in medical education and a rich variety of simulators are now available. Some of these may be readily available to your students or trainees while others including high fidelity manikins may only be available in a central facility such as a clinical skills unit. What simulators do your students have access to?

2. Could greater use be made in your training programme of simulators, simulated patients or virtual patients? Which of the reasons given for simulation apply in your situation?

3. Prepare students for their simulated experience. This includes briefing the students about the expected learning outcomes and what is expected of them in the session. You should familiarise yourself with the simulation prior to the teaching session.

4. Work with the students during their use of the simulator. The extent to which you do this will vary depending on the complexity of the simulator and what is expected of the students.

5. Debrief the students following the simulation. This is an essential part of the process and will allow you to review what the students have learned and to provide them with feedback.

Barrows H.S. An overview of the uses of standardized patients for teaching and evaluating clinical skills. Acad. Med.. 1993;68:443-453.

An early account of how simulated patients can be used in medical education.

Berman N.B., Fall L.H., Chessman A.W., et al. A collaborative model for developing and maintaining virtual patients for medical education. Med. Teach.. 2011;33:319-324.

A description of how virtual patients can be shared between centres.

Cleland J.A., Abe K., Rethans J.J. The use of simulated patients in medical education. AMEE Guide No. 42. Med. Teach.. 2009;31:477-486.

Collins J.P., Harden R.M. The use of real patients, simulated patients and simulators in clinical examinations. AMEE Guide No. 13. Med. Teach.. 1998;20:508-521.

A description of how patients can be represented for teaching and assessment purposes.

Huang G., Reynolds R., Candler C. Virtual patient simulation at U.S. and Canadian medical schools. Acad. Med.. 2007;82:446-451.

An exploration of the educational value of virtual patients.

Issenberg S.B., McGaghie W.C., Petrusa E.R., et al. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning. BEME Guide No. 4. Med. Teach.. 2005;27:10-28.

This issue of Medical Teacher has virtual patients as its theme.