Chapter 2 Signs and symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea and upper airway resistance syndrome

1 INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and upper airway resistance syndrome (UARS) represent two distinct but related entities in the spectrum of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB). OSA is characterized by repetitive partial or complete collapse of the upper airway during sleep, resulting in disruptions of normal sleep architecture and usually associated with arterial desaturations.1 If these respiratory events occur more than five times per hour of sleep and are associated with symptoms, most commonly snoring, excessive daytime fatigue, and witnessed apneas, the term obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome (OSAHS) is applied.2 UARS is a more recent entity and describes patients with symptoms of OSA and polysomnographic evidence of sleep fragmentation but who have minimal obstructive apneas or hypopneas (Respiratory Disturbance Index < 5) and do not exhibit oxyhemoglobin desaturation.

Epidemiologically, OSAHS is estimated to affect 2–5% of the population.3–5 Although it can occur at any age, OSAHS typically presents between the ages of 40 and 60 and increases with age.6–8 Men are twice as likely to develop OSAHS with an estimated prevalence of 4% vs. 2% in women.8 Other at-risk groups include postmenopausal women9–11 who have a two to three-fold increase in prevalence of OSAHS, Pacific Islanders, Hispanic-Americans, and blacks.5,12–15 Additionally, obesity and weight gain have been shown to be important risk factors in the development and progression of OSAHS inmiddle-aged adults.8,16 UARS epidemiology is less well characterized, and to date, there has been no reliable assessment of its prevalence in the general population. Compared to OSAHS, there appears to be no gender bias,17 and patients with UARS are commonly non-obese (mean Body Mass Index of 25 kg/m2)18,19 and are frequently younger (mean age of 37.5 years).18

OSAHS has been shown to be a gradually progressive disease, even in the absence of weight gain.16,20 Some have attributed this slow progression to upper airway damage characterized by palatal denervation with a localized polyneuropathy and inflammatory cell infiltration of the soft palate thought to be caused by snoring-related vibrations and/or large intraluminal pressure oscillations in the setting of obstruction.21,22 As OSAHS worsens in severity, it has been shown to be associated with the development of significant medical co-morbidities, including hypertension, cardiovascular disease, stroke, obesity, and insulin resistance. Furthermore, the presence of OSAHS has been linked to an increased risk of motor vehicle accidents,23–25 impaired daytime performance and quality of life,26,27 and increased mortality independent of co-morbidities.28,29

2 CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

A thorough history (with participation by the bedpartner if possible) and physical examination are integral to the initial evaluation of patients with suspected SDB. However, studies show that the predictive value of these clinical tools is poor. In an observational study of 594 patients, the sensitivity and specificity of subjective clinical impression in determining the presence of OSAHS were 60% and 63% respectively.30 This study also showed that history, physical examination, and clinician impression were only able to predict OSAHS in about 50% of patients. Furthermore, none of the commonly reported symptoms alone has sufficient predictive value to provide an accurate diagnosis of OSAHS.31 Diagnostic accuracy can be improved by identifying constellations of symptoms, such as snoring and witnessed apneas, which increase the sensitivity and specificity of OSAHS diagnosis to 78% and 67% respectively.32,33 Ultimately, overnight polysomnography remains the gold standard in the initial diagnosis of SDB and the only means of distinguishing OSAHS from UARS. However, as such testing can be expensive, time-consuming, and may not always be readily available, a thorough history and physical examination remain important tools to identify those patients who need further evaluation by polysomnography.

3 CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF OSA

3.1 SLEEP-RELATED (NOCTURNAL)SYMPTOMS

Snoring is the most frequently reported symptom in OSAHS and is found in 70–95% of such patients.34 Typically, the snoring may have been present for many years but has increased with intensity over time and is further exacerbated by nighttime alcohol consumption, weight gain, sedative medications, sleep deprivation, or supine position. Snoring may become so loud as to be greatly disruptive to the bedpartner and is often a source of relationship discord; in one report, 46% of patients slept in a different room from their partners.35 The characteristic snoring pattern associated with OSAHS is one of loud snores or brief gasps alternating with 20- to 30-second periods of silence. Because snoring is so common in the general population (35–45% in men, 15–28% in women8,36), it isa poor predictor of OSAHS; however, only 6% of patients with OSAHS do not report snoring and its absence makes OSAHS unlikely.37 Corroboration with bedpartners is important as approximately 75% of patients who deny snoring are found to snore during objective measurement.38

Witnessed apneas are observed by up to 75% of bedpartners and are the second most common nocturnal symptom reported in OSAHS.30,39 Occasional apneas are normal and do not cause symptoms; however, as the frequency of apneas increases, a certain threshold may be exceeded which results in symptomatic disease. This threshold is variable and unique to each patient such that some patients with a low Respiratory Disturbance Index (RDI) may be profoundly symptomatic while others with frequent respiratory events present with relatively few complaints.40 Particularly in OSAHS of milder severity, the apneic episodes are usually associated with maintenance of respiratory movements and are terminated by loud snorts, gasps, moans, or other vocalizations and sometimes with brief awakenings and body movements. In more severe disease, cyanosis can occur along with the cessation of respiratory movement during the apnea which will often cause considerable distress to the bedpartner. Body movements at the time of arousals in severe OSAHS can be frequent and sometimes violent. Patients themselves are rarely aware of the apneas, vocalizations, frequent arousals, movements, or brief awakenings, although the elderly are particularly sensitive to the frequent nocturnal awakenings and will report insomnia and unrefreshing sleep.1

Nocturnal dyspnea, sometimes described by patients as a sensation of choking or suffocating, has been observed in 18–31% of patients with OSAHS.35,41,42 These episodes typically occur with arousal, are associated with feelings of panic and anxiety, and generally subside within a few seconds. During apneas or hypopneas, greater negative intrathoracic pressures are generated as patients increase their inspiratory efforts to overcome the upper airway obstruction. This increases venous return to the heart and thus elevates pulmonary capillary wedge pressure which produces the sensation of dyspnea.43,44 Other important causes of paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea include left heart failure, nocturnal asthma, acute laryngeal stridor, or Cheyne–Stokes respirations; however, these episodes tend to be longer in duration and may also occur during the daytime.39 Further investigation may be warranted to differentiate OSAHS from these other entities although they may also coexist.

Other common symptoms of OSAHS include drooling in about one-third and dry mouth in up to three-quarters of patients.35 In one study of 668 patients with suspected SDB, dry mouth was observed in 31.4% of patients with confirmed OSA as compared to 16.4% in primary snorers and 3.2% in normal subjects.45 Furthermore, there was a linear increase in prevalence of dry mouth as the severity of OSA increased. Sleep bruxism is also a common finding, occurring in 4.4% of the general population, with OSAHS patients being at higher risk (odds ratio 1.8) of reporting sleep bruxism.46 In a small study of 21 patients, 54% of those with mild OSA and 40% of those with moderate disease were diagnosed with bruxism which was not observed to be directly associated with respiratory events but rather seemed to be related to sleep disruption and arousal.47–49

In addition to the common complaint of restless sleep and frequent awakenings, up to half of patients with OSAHS report nocturnal sweating that typically occurs in the neck and upper chest area.41,42 This symptom is likely due to the increased work of breathing and respiratory effort in the setting of repetitive airway obstruction,50 but may also be a manifestation of the autonomic instability observed in OSAHS. Similar to dyspnea, nocturnal diaphoresis is a highly non-specific symptom with a broad differential diagnosis, including perimenopausal state, thyroid disease, tuberculosis, lymphoma, and myriad other co-morbid conditions that warrant further investigation.51

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) also occurs with greater frequency in patients with OSAHS with prevalence rates of 64–73%, but appears to be unrelated to the severity of SDB.52,53 As GER and OSA share several risk factors, the exact relationship between the two entities has been difficult to characterize. However, it has been postulated that OSAHS may contribute to GER via the following mechanism: upper airway obstruction results in increased intraabdominal pressure combined with more negative intrathoracic pressure that produces an increased transdiaphragmatic pressure gradient, thereby promoting reflux of gastric contents into esophagus.50 In a long-term study of 331 patients, treatment of OSAHS with nasal positive pressure resulted in a 48% decrease in the frequency of nocturnal GER symptoms with higher pressures being associated with greater improvement, suggesting that OSAHS may indeed be a causal factor in nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux.54

Nocturia has also been observed with increased frequency in OSAHS with a reported 28% of patients experiencing four to seven episodes nightly.55 The presence and frequency of nocturia have been shown to be related to the severity of OSA,55,56 and the proposed physiologic mechanisms include increased atrial natriuretic peptide secretion with a corresponding increase in total urine output,57 or an increase in intraabdominal pressure. One study of 80 patients showed that although a majority of nocturnal awakenings were actually due to sleep-related phenomena (78.3% of 121 total awakenings), patients voluntarily urinated with each arousal and were only able to identify the correct source of the awakenings in five instances (4.9%).58 These data show that patients mistakenly attributed their arousals to need to urinate when they were in fact due to SDB, suggesting that patient misperception may be a contributing factor to the increased frequency of reported nocturia in OSAHS.

3.2 DAYTIME SYMPTOMS

While the nocturnal symptoms of OSAHS are characteristic and tend to be more specific for the disease, the common daytime symptoms are less specific as they can result from abnormal sleep of any cause. Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) is the most common daytime complaint in patients with OSAHS;30,35,41 however, as 30–50% of the general population also report moderate to severe sleepiness,8,59 this symptom alone is a poor predictor of OSAHS. EDS is caused by sleep fragmentation leading to frequent arousals and insufficient sleep;40 it is manifested by the inappropriate urge to sleep, particularly during relaxing, sedentary activities (i.e. watching television, reading). As it worsens, the inability to control sleepiness can result in dozing during meetings, active conversations, and at mealtimes. When severe, EDS can be a cause of motor vehicle and machinery accidents, poor school or job performance, and relationship discord.

Establishing the presence and severity of inappropriate daytime sleepiness can be challenging. EDS is often insidious, may be subtle, and is often confused with fatigue or lethargy. Patients themselves often have a poor perception of EDS severity and underestimate their level of impairment.60 Co-morbidities such as chronic insomnia, depression, fibromyalgia, and other organic diseases, as well as medication use or substance abuse, may contribute to the symptom of inappropriate sleepiness. The clinician should focus on the urge to sleep in passive situations, since both physical and mental activity can mask underlying EDS.

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) is a simple, self-administered questionnaire that is a quick and inexpensive tool with a high test–retest reliability,2 and is thus a practical means of measuring the general level of daytime sleepiness. Patients are asked to assess their probability of falling asleep in eight situations commonly encountered in daily life, and a numeric score is tabulated. Higher Epworth scores, reflecting increased average sleep propensity, are able to distinguish patients with OSAHS from primary snorers and appear to correlate with severity of OSA as well as sleep latency measured objectively during multiple sleep latency testing.35,61,62 The major disadvantage of the ESS is its reliance on subjective reporting by patients who may underestimate or intentionally underreport severity of daytime sleepiness.39

Morning or nocturnal headaches are reported in about half of patients with OSAHS, are typically dull and generalized, last 1 to 2 hours, and may require analgesics.1,35 However, this symptom is non-specific as morning headaches occur in 5–8% of the general population and have been associated with many other entities, including other sleep disorders as well as depression, anxiety, and various medical conditions.63,64 These headaches have been attributed to nocturnal episodes of oxygen desaturation, hypercapnia, cerebral vasodilatation with resultant increases in intracranial pressure, and impaired sleep quality with corresponding polysomnographic evidence of decreased total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and amount of REM sleep.65,66 It has been observed that treatment of the underlying OSAHS results in disappearance of the morning headaches.

Neurocognitive impairment has also been observed in patients with OSAHS, although there is no practical method of quantifying such deficits in this setting. The processes most affected in OSAHS appear to be vigilance, executive functioning, and motor coordination.67 Decreased vigilance is a result of sleep fragmentation, which can also lead to diminished concentration and memory (short term and long term). However, psychomotor impairment appears to be largely related to hypoxemia with more severe OSAHS potentially resulting in irreversible anoxic brain damage.68–70 This hypothesis is supported by the observation that psychomotor deficits in patients with severe OSAHS are only partially reversible with treatment of the underlying sleep disorder with continuous positive airway pressure.68,69

Patients with OSAHS have a tendency to report decrements in their quality of life and often experience concomitant mood and personality changes. Depression is the most common mood symptom, and daytime sleepiness has been identified as a reliable predictor.63,71 Other behavioral manifestations of OSAHS include anxiety, irritability, aggression, and emotional lability.72 Treatment with continuous positive airway pressure has been shown to ameliorate symptoms of depression and thereby improve quality of life in some patients.73,74 Sexual dysfunction, manifested primarily as erectile dysfunction and decreased libido, is also associated with OSAHS, and appears to be fully reversible with treatment of the underlying sleep disorder75,76 (Table 2.1).

| Nocturnal symptoms | Daytime symptoms |

|---|---|

| Snoring | Excessive daytime sleepiness |

| Witnessed apneas | Morning headaches |

| Dyspnea (choking/gasping) | Neurocognitive impairment: |

| DroolingDry mouth | vigilance (secondary impact on concentration and memory) |

| Bruxism | executive functioning |

| Restless sleep/frequent arousals | motor coordination |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | Diminished quality of life |

| Nocturia | Mood and personality changes: |

decreased libidoimpotence

abnormal menses

3.3 CLINICAL SIGNS

Physical examination of the patient with suspected OSAHS and UARS can reveal characteristic findings suggestive of upper airway obstruction and associated SDB. Blood pressure should always be recorded as both hypertension and hypotension have been found in patients with SDB. Obesity has also been frequently associated with OSAHS,8,37 particularly in women, and measurement of height and weight followed by calculation of Body Mass Index (kg/m2) to define and quantify obesity are important components of the physical examination. Grunstein and colleagues demonstrated that a BMI of at least 25 kg/m2 was associated with a 93% sensitivity and 74% specificity for OSAHS.77 However, 18 to 40% of affected patients are less than 20% above ideal body weight,35 and patients with UARS are typically non-obese.

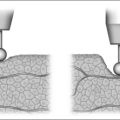

Increased neck circumference has consistently been shown to be a more reliable clinical predictor of OSAHS and has been shown in one study to correlate with severity of disease.30,78,79 Katz and colleagues showed that patients with OSAHS had an increased mean neck circumference (measured at the superior aspect of the cricothyroid membrane with the patient upright) of 43.7 cm ± 4.5 cm versus 39.6 cm ± 4.5 cm in control subjects (P=0.0001).80 Likewise, Kushida et al. found that neck circumference of 40 cm was associated with a sensitivity of 61% and specificity of 93% for OSAHS.81 Thus, neck circumference should be routinely measured during physical examination, and if greater than 40 cm, underlying OSAHS must be considered and further investigated.

The craniofacial abnormalities most commonly associated with airway narrowing and SDB are retrognathia82 and high arched palate. Retrognathia, also known as mandibular retroposition, is a result of delayed growth of the mandible, maxilla, or both and is associated with posterior displacement of the tongue base.81 Thus, the finding of retrognathia signifies a narrowed upper airway, particularly in the region of the retroglossal space. Patients with SDB are also commonly found to have high arched hard palates due to the early, forced expansion of the lateral palatine processes over the posteriorly displaced tongue prior to midline fusion. The significance of retrognathia and high arched palate in SDB was supported by Kushida et al., who described four craniofacial parameters indicative of airway narrowing: maxillary intermolar distance, mandibular intermolar distance, palatal height, and dental overjet (a sign of mandibular insufficiency).81 Palpation of the temporomandibular joint with mouth opening may reveal varying degrees of dislocation (TMJ ‘click’) which confers greater risk of airway collapse in the supine patient due to posterior displacement during sleep.50

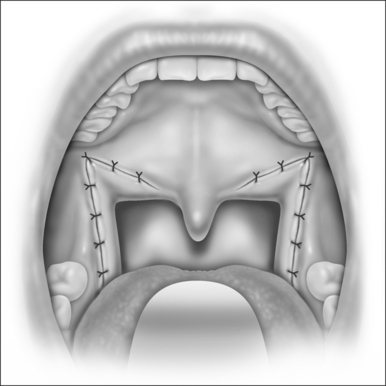

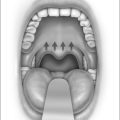

Examination of the pharyngeal structures may reveal further evidence of airway restriction and underlying SDB. These findings include macroglossia (often associated with lateral lingual scalloping by adjacent teeth), erythema and edema of the uvula due to snoring, and redundant lateral wall soft tissue with tonsillar pillar hypertrophy, and tonsillar enlargement (graded with 0–4 scale) which is a particularly significant cause of obstruction in children.50 The degree of oropharyngeal crowding can be further characterized by the Friedman tongue position, formerly called the modified Mallampati score, which incorporates visual assessment of size, length, and height of the soft palate and uvula and is similar to the Friedman Tongue Index (further described in other sections of this text). These structures represent the anterior limit of the upper airway, and a low-lying, elongated, or enlarged soft palate/uvula decreases airway caliber and increases susceptibility to obstruction. This scoring system was initially developed to assess difficulty of airway intubation; a numeric grade from 1 to 4 is assigned depending on the relative size and positions of the soft palate, tip of the uvula, tongue, and tonsillar pillars. The Friedman tongue position has been shown to be an independent predictor of both the presence and severity of OSA with an average two-fold increase in odds of having OSA for every one point increase in the Friedman tongue position.83 However, the gold standard in pharyngeal evaluation remains direct laryngoscopy as it is the most reliable means of identifying actual static and dynamic restriction of the retroglossal or retropalatal space, which are common sites of obstruction during sleep.

Abnormalities of dentition are often observed in patients with SDB and are typically reflective of maxillomandibular deficiencies and airway crowding. Patients with these physical features will frequently report previous wisdom teeth extraction and/or childhood orthodontia. Dental overjet is a common sign of underlying mandibular retroposition and refers to the forward extrusion of the upper incisors beyond the lower incisors by more than 2.2 mm. Findings of dental malocclusion and overlapping teeth indicate a restricted oral cavity that is prone to collapse. Because OSAHS has been associated with bruxism, evidence of teeth grinding should also be noted.

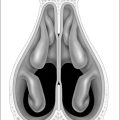

Examination of the nose is the last important component of the upper airway evaluation. Although nasal obstruction is rarely the sole cause of SDB, it appears to occur with higher frequency in OSAHS84 and may contribute significantly to increased upper airway resistance and the development of UARS.85 Furthermore nasal obstruction in children may cause chronic mouth breathing and secondarily result in abnormal craniofacial development. Inspection of the nose should note the size and symmetry of nares, collapsibility of internal/external valves and nasal alae with inspiration, evidence of septal deviation or prior nasal trauma, and hypertrophy of the inferior nasal turbinates.50 Identifying nasal obstruction can be particularly important in patients with SBD who have difficulty tolerating nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy as treatments such as septoplasty and turbinate reduction can decrease nasal resistance with resultant improvements in CPAP compliance and comfort (Table 2.2).

| Craniofacial |

| Retrognathia |

| High arched palate |

| Temporomandibular dislocation |

| Pharyngeal |

| Macroglossia |

| Erythema/edema of uvula |

| Elongated, low-lying soft palate |

| Tonsillar pillar hypertrophy |

| Tonsillar enlargement |

| Retropalatal, retroglossal space restriction |

| Dental |

| Overjet |

| Malocclusion |

| Bruxism |

| Orthodontia |

| Nasal |

| Asymmetric, small nares |

| Inspiratory collapse of alae and internal valves |

| Septal deviation |

| Inferior turbinate hypertrophy |

4 CLINICAL PRESENTATION OF UARS

UARS was first described in children in 1982,86 although it was later observed that a population of adults with chronic daytime sleepiness but without typical polysomnographic evidence of OSA (apneas, hypopneas, or oxygen desaturations) exhibited increased inspiratory effort during sleep detected by esophageal manometry that resulted in transient, repetitive alpha EEG arousals.18 Although these increases in upper airway resistance were not sufficient to cause detectable airflow abnormalities or oxyhemoglobin desaturation on routine sleep testing, the required increase in inspiratory work to overcome the elevated resistive load appeared to lead to recurrent arousals and sleep fragmentation and daytime hypersomnolence.

As such, there is considerable overlap between the symptoms of OSAHS and UARS, with excessive daytime sleepiness, snoring, and restless sleep being frequent complaints in UARS. However, key differences do exist, and recent data suggest that chronic insomnia is much more common in UARS than in OSAHS.50 Many adult UARS patients report frequent nocturnal awakenings with an inability to fall back asleep (sleep maintenance insomnia) as well as difficulties with sleep initiation (sleep-onset insomnia). Chronic insomnia in UARS has been attributed to cognitive-behavioral conditioning resulting from frequent sleep disruptions.87 Parasomnias are more prevalent in young patients with UARS, with sleepwalking with or without night terrors and associated confusional arousal being most common.88 Treatment of UARS typically results in resolution of the parasomnias.

While daytime symptoms are also similar to those seen in OSAHS, adult patients with UARS are more likely to complain of daytime fatigue rather than sleepiness.50 Cold hands and feet are described in half of UARS patients, and about a quarter (typically teenagers and young adults) will report symptoms of dizziness or orthostatic hypotension, with lightheadedness upon rapid change of positions.89 This orthostatic intolerance may be related to the finding that roughly a fifth of UARS patients exhibit resting hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 105 mm Hg, diastolic <65 mm Hg) as compared to OSAHS,90 which is typically associated with hypertension.91–93

Lastly, Gold and colleagues observed that symptoms closely resembling those found in the functional somatic syndromes were more often reported by patients with UARS than by those with OSAHS.17 Complaints such as headache, sleep-onset insomnia, and irritable bowel syndrome were more prevalent in UARS and decreased progressively as severity of SDB increased. Because of the frequency of these and other related non-specific somatic complaints such as fainting and myalgias, it is not uncommon for UARS to be misinterpreted as one of the many functional somatic syndromes, including chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, temporomandibular joint syndrome, or migraine/tension headache syndrome (Table 2.3).

Table 2.3 Major clinical features differentiating OSAHS and UARS

| OSAHS | UARS |

|---|---|

| Men . women | Men=women |

| Obese | Non-obese |

| Hypertension | Hypotension |

| Hypersomnia, excessive daytime sleepiness | Insomnia, fatigue |

| Rare somatic symptoms | Somatic symptoms |

5 SLEEP-DISORDERED BREATHING IN WOMEN

In the early descriptions of OSAHS, the vast majority of data came from studies performed on male subjects, and women were characterized as the ‘forgotten gender.’94 Preliminary observations of SDB in women appeared to suggest a strong correlation with obesity, resulting in a clear bias against the recognition of this entity in non-obese women (BMI < 30 kg/m2), even in the presence of clinical and polysomnographic findings of OSAHS.94,95 As a result, women experienced longer durations of symptoms and significant delays in appropriate referral and diagnosis compared to age-matched men.94,96

It is now recognized that women often present with different symptoms of SDB, report ‘typical’ symptoms less frequently, and may underestimate symptom severity as compared to men, which may be additional factors contributing to disease underrecognition in this population.97 Symptoms more commonly observed in women include non-specific somatic complaints, such as insomnia, fatigue, myalgias, and morning headache.17,98 Amenorrhea and dysmenorrhea have been reported in 43% of women with SDB.94 Depression, anxiety, and social isolation occur with higher frequency in women as compared to men with SDB.94,99 While women with OSAHS do tend to be more obese than men with similar disease severity, those with UARS are typically non-obese, younger, and have fewer witnessed apneas.18,100

1. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. In: The International Classification of Sleep Disorders Revised Diagnostic and Coding Manual; 2001, pp. 52–58.

2. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Sleep related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. Sleep. 1999;22:667-689.

3. Bresnitz EA, Goldberg R, Kosinski RM. Epidemiology of obstructive sleep apnea. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16:210-227.

4. Olson LG, King MT, Hensley MJ, et al. A community study of snoring and sleep-disordered breathing. Prevalence. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:711-716.

5. Kripke DF, Ancoli-Israel S, Klauber MR, et al. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in ages 40–64 years: a population-based survey. Sleep. 1997;20:65-76.

6. Ancoli-Israel S. Epidemiology of sleep disorders. Clin Geriatr Med. 5, 1989.

7. Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Ten Have T, et al. Effects of age on sleep apnea in men: I. Prevalence and severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:144-148.

8. Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, et al. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230-1235.

9. Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin HM, et al. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in women: effects of gender. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:608-613.

10. Young T. Menopausal status and sleep-disordered breathing in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1181-1185.

11. Redline S, Kump K, Tishler PV, et al. Gender differences in sleep disordered breathing in a community-based sample. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:722-726.

12. Grunstein RR, Lawrence S, Spies JM. Snoring in paradise – the Western Samoa Sleep Survey. Eur Respir J. 1989;2(Suppl 5):4015.

13. Schmidt-Nowara WW, Coultas DB, Wiggins C, et al. Snoring in a Hispanic-American population. Risk factors and association with hypertension and other morbidity. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:597-601.

14. Friedman M, Bliznikas D, Klein M, et al. Comparison of the incidences of obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome in African–Americans versus Caucasian–Americans. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:545-550.

15. Ancoli-Israel S, Klauber MR, Stepnowsky C, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in the African–American elderly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:1946-1949.

16. Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, et al. Longitudinal study of moderate weight change and sleep-disordered breathing. JAMA. 2000;284:3015-3021.

17. Gold AR, Dipalo F, Gold MS, et al. The symptoms and signs of upper airway resistance syndrome: a link to the functional somatic syndromes. Chest. 2003;123:87-95.

18. Guilleminault C, Stoohs R, Clerk A, et al. A cause of daytime sleepiness: the upper airway resistance syndrome. Chest. 1993;104:781-787.

19. Woodson BT. Upper airway resistance syndrome after uvulopalatopharyngoplasty for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;114:457-461.

20. Pendlebury ST, Pepin JL, Veale D, et al. Natural evolution of moderate sleep apnoea syndrome: significant progression over a mean of 17 months. Thorax. 1997;52:872-878.

21. Boyd JH, Petrof BJ, Hamid Q, et al. Upper airway muscle inflammation and denervation changes in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:541-546.

22. Friberg D, Ansved T, Borg K, et al. Histological indications of a progressive snorers disease in an upper airway muscle. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:586-893.

23. George CF, Nickerson PW, Hanly PJ, et al. Sleep apnoea patients have more automobile accidents. Lancet. 1987;2:447.

24. Findley LJ, Weiss JW, Jabour ER. Drivers with untreated sleep apnea. A cause of death and serious injury. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151:1451-1452.

25. Young T, Blustein JF, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and motor vehicle accidents in a populations-based sample of employed adults. Sleep. 1997;20:608-613.

26. Chugh DK, Dinges DF. Mechanisms of sleepiness in obstructive sleep apnea. In: Pack AI, editor. Sleep Apnea: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment, Lung Biology in Health and Disease. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2002:265-285.

27. Jenkinson C, Stradling J, Petersen S. Comparison of three measures of quality of life outcome in the evaluation of continuous positive airways pressure therapy for sleep apnoea. J Sleep Res. 1997;6:199-204.

28. Partinen MJ, Guilleminault C. Long-term outcome for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome patients. Mortality. Chest. 1988;94:1200-1204.

29. Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, et al. Obstructive sleep apneaas a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2034-2041.

30. Hoffstein V, Szalai JP. Predictive value of clinical features in diagnosing obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 1993;16:118-122.

31. Flemons WW, Whitelaw WA, Brant R, et al. Likelihood ratios for a sleep apnea clinical prediction rule. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:1279-1285.

32. Kapuniai LE, Andrew DJ, Crowell DH, et al. Identifying sleep apnea from self-reports. Sleep. 1988;11:430-436.

33. Young T, Shahar E, Nieto FJ, et al. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling adults: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:893-900.

34. Whyte KF, Allen MB, Jeffrey AA, et al. Clinical features of the sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Q J Med. 1989;72:659-666.

35. Kales A, Cadieux RJ, Bixler EO, et al. Severe obstructive sleep apnea. I: Onset, clinical course, and characteristics. J Chron Dis. 1985;38:419-425.

36. Ohayon MM, Guilleminault C, Priest RG, et al. Snoring and breathing pauses during sleep: telephone interview survey of a United Kingdom population sample. BMJ. 1997;314:860-863.

37. Strohl KP, Redline S. Recognition of obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:279-289.

38. Hoffstein V, Mateika S, Anderson D. Snoring: is it in the ear of the beholder? Sleep. 1994;17:522-526.

39. Schlosshan D, Elliott MW. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of the obstructive sleep apnoea hypopnoea syndrome. Thorax. 2004;59:347-352.

40. Roehrs T, Zorick F, Wittig R, et al. Predictors of objective level of daytime sleepiness in patients with sleep-related disorders. Chest. 1989;95:1202-1206.

41. Maislin G, Pack AI, Kribbs NB, et al. A survey screen for prediction of apnea. Sleep. 1995;18:158-166.

42. Coverdale SG, Read DJ, Woolcock AJ, et al. The importance of suspecting sleep apnoea as a common cause of excessive daytime sleepiness: further experience from the diagnosis and management of 19 patients. Aust NZ J Med. 1980;10:284-288.

43. Buda AJ, Schroeder JS, Guilleminault C. Abnormalities of pulmonary artery wedge pressure in sleep-induced apnea. Int J Cardiol. 1981;1:67-74.

44. Hetzel M, Kochs M, Marx N, et al. Pulmonary hemodynamics in obstructive sleep apnea: frequency and causes of pulmonary hypertension. Lung. 2003;181:157-166.

45. Oksenberg A, Froom P, Melamed S. Dry mouth upon awakening in obstructive sleep apnea. J Sleep Res. 2006;15:317-320.

46. Ohayon MM, Li KK, Guilleminault C. Risk factors for sleep bruxism in the general population. Chest. 2001;119:53-61.

47. Sjoholm TT, Lowe AA, Miyamoto K, et al. Sleep bruxism inpatients with sleep-disordered breathing. Arch Oral Biol. 2000;45:889-896.

48. Macaluso GM, Guerra P, Di Giovanni G, et al. Sleep bruxism is a disorder related to periodic arousals during sleep. J Dent Res. 1998;77:565-573.

49. Okeson JP, Phillips BA, Berry DT, et al. Nocturnal bruxing events in subjects with sleep-disordered breathing and control subjects. J Craniomandib Disord. 1991;5:258-264.

50. Guilleminault C, Bassiri A. Clinical features and evaluation of obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome and upper airway resistance syndrome. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 4th edn. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005; 2005:1043-1052.

51. Viera AJ, Bond MM, Yates SW. Diagnosing night sweats. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:1019-1024.

52. Valipour A, Makker HK, Hardy R, et al. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux in subjects with a breathing sleep disorder. Chest. 2002;121:1748-1753.

53. Wise SK, Wise JC, DelGaudio JM. Gastroesophageal reflux and laryngopharyngeal reflux in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;135:253-257.

54. Green BT, Broughton WA, O’Connor JB. Marked improvement in nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux in a large cohort of patients with obstructive sleep apnea treated with continuous positive airway pressure. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:41-45.

55. Hajduk IA, Strollo PJJ, Jasani RR, et al. Prevalence and predictors of nocturia in obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome – a retrospective study. Sleep. 2003;26:61-64.

56. Fitzgerald MP, Mulligan M, Parthasarathy S. Nocturic frequency is related to severity of obstructive sleep apnea, improves with continuous positive airways treatment. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1399-1403.

57. Umlauf MG, Chasens ER, Greevy RA, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea, nocturia and polyuria in older adults. Sleep. 2004;27:139-144.

58. Pressman MR, Figueroa WG, Kendrick-Mohamed J, et al. Nocturia. A rarely recognized symptom of sleep apnea and other occult sleep disorders. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:545-550.

59. Duran J, Esnaola S, Rubio R, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea and related clinical features in a population-based sample of subjects aged 30 to 70 yr. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:685-689.

60. Engleman HM, Hirst WS, Douglas NJ. Under reporting of sleepiness and driving impairment in patients with sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. J Sleep Res. 1997;6:272-275.

61. Johns MW. Daytime sleepiness, snoring, and obstructive sleep apnea. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Chest. 1993;103:30-36.

62. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540-545.

63. Ohayon MM. Prevalence and risk factors of morning headaches in the general population. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:97-102.

64. Ulfberg J, Carter N, Talback M, et al. Headache, snoring and sleep apnea. J Neurol. 1996;243:621-625.

65. Goder R, Friege L, Fritzer G, et al. Morning headaches in patients with sleep disorders: a systematic polysomnographic study. Sleep Med. 2003;4:385-391.

66. Provini F, Vetrugno R, Lugaresi E, et al. Sleep-related breathing disorders and headache. Neurol Sci. 2006;27(Suppl 2):S149-S152.

67. Beebe DW, Groesz L, Wells C, et al. The neuropsychological effects of obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis of norm-referenced and case-controlled data. Sleep. 2003;26:298-307.

68. Ferini-Strambi L, Baietto C, Di Gioia MR, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA): partial reversibility after continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). Brain Res Bull. 2003;61:87-92.

69. Montplaisir J, Bedard MA, Richer R, et al. Neurobehavioral manifestations in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome before and after treatment with continuous positive airway pressure. Sleep. 1992;15(Suppl 6):S17-S19.

70. Naegele B, Thouvard V, Pepin JL, et al. Deficits of cognitive executive functions in patients with sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep. 1995;18:43-52.

71. Kjelsberg FN, Ruud EA, Stavem K. Predictors of symptoms of anxiety and depression in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2005;6:341-346.

72. Day R, Gerhardstein R, Lumley A, et al. The behavioral morbidity of obstructive sleep apnea. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1999;41:341-354.

73. Kawahara S, Akashiba T, Akahoshi T, et al. Nasal CPAP improves the quality of life and lessens the depressive symptoms in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Intern Med. 2005;44:422-427.

74. Schwartz DJ, Kohler WC, Karatinos G. Symptoms of depression in individuals with obstructive sleep apnea may be amenable to treatment with continuous positive airway pressure. Chest. 2005;128:1304-1309.

75. Goncalves MA, Guilleminault C, Ramos E, et al. Erectile dysfunction, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and nasal CPAP treatment. Sleep Med. 2005;6:333-339.

76. Teloken PE, Smith EB, Lodowsky C, et al. Defining association between sleep apnea syndrome and erectile dysfunction. Urology. 2006;67:1033-1037.

77. Grunstein R, Wilcox I, Yang TS, et al. Snoring and sleep apnoea in men: association with central obesity and hypertension. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1993;17:533-540.

78. Davies RJ, Stradling JR. The relationship between neck circumference, radiographic pharyngeal anatomy, and the obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Eur Respir J. 1990;3:509-514.

79. Stradling J, Crosby J. Predictors and prevalence of obstructive sleep apnoea and snoring in 1001 middle aged men. Thorax. 1991;46:85.

80. Katz I, Stradling J, Slutsky AS, et al. Do patients with obstructive sleep apnea have thick necks? Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:1228-1231.

81. Kushida CA, Efron B, Guilleminault C. A predictive morphometric model for the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:581-587.

82. Jamieson A, Guilleminault C, Partinen M, et al. Obstructive sleep apneic patients have craniomandibular abnormalities. Sleep. 1986;9:469-477.

83. Nuckton TJ, Glidden DV, Browner WS, et al. Physical examination: Mallampati score as an independent predictor of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2006;29:903-908.

84. Zonato AI, Bittencourt LR, Martinho FL, et al. Association of systematic head and neck physical examination with severity of obstructive sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:973-980.

85. Guilleminault C, Kim YD, Stoohs RA. Upper airway resistance syndrome. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 1995;7:397-406.

86. Guilleminault C, Winkle R, Korobkin R, et al. Children and nocturnal snoring: evaluation of the effects of sleep related respiratory resistive load and daytime functioning. Eur J Pediatr. 1982;139:165-171.

87. Guilleminault C, Palombini L, Poyares D, et al. Chronic insomnia, post menopausal women, and SDB, part 2: comparison of non drug treatment trials in normal breathing and UARS post menopausal women complaining of insomnia. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:617-623.

88. Guilleminault C, Palombini L, Pelayo R, et al. Sleepwalking and sleep terrors in prepubertal children: what triggers them? Pediatrics. 2003;111:17-25.

89. Bao G, Guilleminault C. Upper airway resistance syndrome – one decade later. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2004;10:461-467.

90. Guilleminault C, Faul JL, Stoohs R. Sleep-disordered breathing and hypotension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1242-1247.

91. Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin HM, et al. Association of hypertension and sleep-disordered breathing. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2289-2295.

92. Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA. 2000;283:1829-1836.

93. Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, et al. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1378-1384.

94. Guilleminault C, Stoohs R, Kim YD, et al. Upper airway sleep disordered breathing in women. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:493-501.

95. Guilleminault C, Stoohs R, Clerk A, et al. Excessive daytime somnolence in women with abnormal respiratory effort during sleep. Sleep. 1993;16:S137-S138.

96. Larsson LG, Lindberg A, Franklin KA, et al. Gender differences in symptoms related to sleep apnea in a general population and in relation to referral to sleep clinic. Chest. 2003;124:204-211.

97. Kapsimalis F, Kryger MH. Gender and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, Part 1: Clinical features. Sleep. 2002;25:412-419.

98. Chervin RD. Sleepiness, fatigue, tiredness, and lack of energy in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 2000;118:372-379.

99. Shepertycky MR, Banno K, Kryger MH, Differences between men and women in the clinical presentation of patients diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. 2005; 28:309–314

100. Quintana-Gallego E, Carmona-Bernal CC, et al. Gender differences in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a clinical study in 1166 patients. Respir Med. 2004;98:984-989.