3 Shoulder Injuries

Background

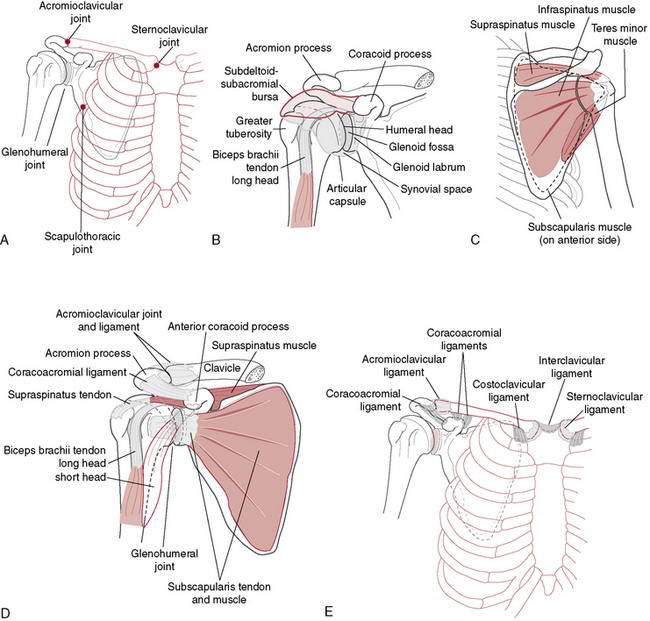

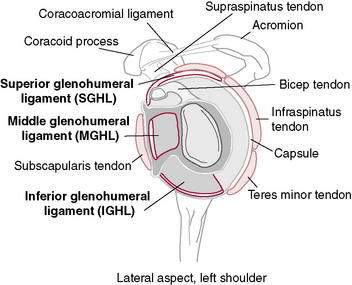

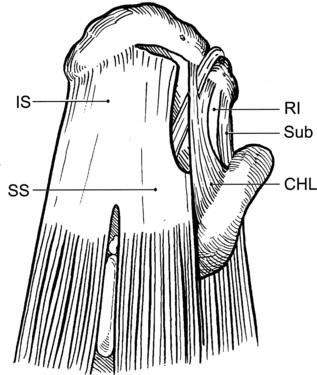

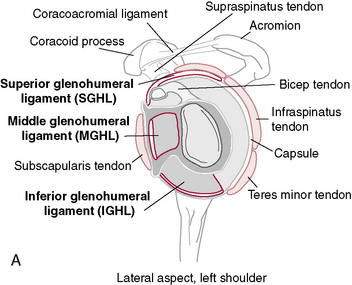

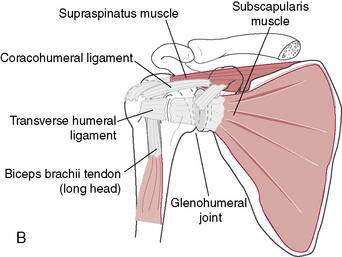

“Unrestricted” motion occurs at the GH joint as a result of its osseous configuration (Fig. 3-1). A large humeral head articulating with a small glenoid socket allows extremes of motion at the expense of the stability that is seen in other joints (Table 3-1). Similarly, the scapula is very mobile on the thoracic wall. This enables it to follow the humerus, positioning the glenoid appropriately while avoiding humeral impingement on the acromion. Osseous stability of the GH joint is enhanced by the fibrocartilaginous labrum, which functions to enlarge and deepen the socket while increasing the conformity of the articulating surfaces. However, the majority of the stability at the shoulder is determined by the soft tissue structures that cross it. The ligaments and capsule form the static stabilizers and function to limit translation and rotation of the humeral head on the glenoid. The superior GH ligament has been shown to be an important inferior stabilizer. The middle GH ligament imparts stability against anterior translation with the arm in external rotation and abduction less than 90 degrees. The inferior GH ligament is the most important anterior stabilizer with the shoulder in 90 degrees of abduction and external rotation, which represents the most unstable position of the shoulder (Fig. 3-2).

Table 3-1 Normal Joint Motions and Bony Positions Around the Shoulder Joint

| Scapula | |

| Rotation through arc of 65 degrees with shoulder abduction | |

| Translation on thorax up to 15 cm | |

| Glenohumeral Joint | |

| Abduction | 140 degrees |

| Internal/external rotation | 90 degrees/90 degrees |

| Translation | |

| Anterior–posterior | 5–10 mm |

| Inferior–superior | 4–5 mm |

| Total rotations | |

| Baseball | 185 degrees |

| Tennis | 165 degrees |

The muscles make up the dynamic stabilizers of the GH joint and impart stability in a variety of ways. During muscle contraction, they provide increased capsuloligamentous stiffness, which increases joint stability. They act as dynamic ligaments when their passive elements are put on stretch (Hill 1951). Most important, they make up the components of force couples that control the position of the humerus and scapula, helping to appropriately direct the forces crossing the GH joint (Poppen and Walker 1978) (Table 3-2).

Table 3-2 Forces and Loads on the Shoulder in Normal Athletic Activity

| Rotational Velocities | |

|---|---|

| Baseball | 7000 degrees/sec |

| Tennis serve | 1500 degrees/sec |

| Tennis forehand | 245 degrees/sec |

| Tennis backhand | 870 degrees/sec |

| Angular Velocities | |

| Baseball | 1150 degrees/sec |

| Acceleration Forces | |

| Internal rotation | 60 Nm |

| Horizontal adduction | 70 Nm |

| Anterior shear | 400 Nm |

| Deceleration Forces | |

| Horizontal abduction | 80 Nm |

| Posterior shear | 500 Nm |

| Compression | 70 Nm |

General Principles of Shoulder Rehabilitation

Designing a rehabilitation program should take several factors into account:

Importance of the History in the Diagnosis of Shoulder Pathology

Richard Romeyn, MD, and Robert C. Manske, PT, DPT, SCS, MEd, ATC, CSCS

When taking a history, the crucial elements about which one must inquire are as follows:

Scapulothoracic Dyskinesia, Core Stability Deficits, and Other Fitness or Technique-Related Provocations

General shoulder rehabilitation goals

Range of Motion

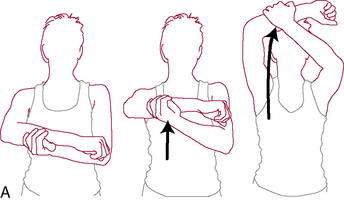

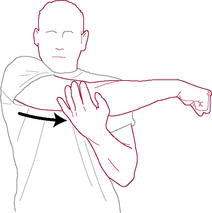

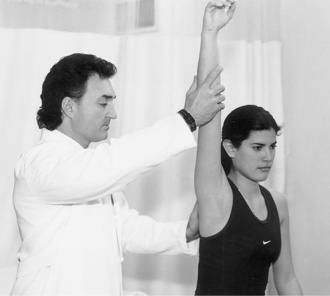

Once the intake evaluation is completed, the therapist should be more comfortable anticipating the patient’s response to the therapeutic regimen. One of the main keys to recovery is to normalize motion. Early professions relied on visual estimations or “quick” tests to assess shoulder motion. These tests include combined shoulder movements such as the Apley’s scratch test (Fig. 3-3), reaching across the body to the other shoulder (Fig. 3-4), or reaching behind the back to palpate the highest spinous process (Fig. 3-5). These quick tests are great to observe for overall asymmetry, but they cannot give an idea of isolated losses objectively.

Figure 3-5 Reaching behind the back to palpate the highest spinous process to determine range of motion.

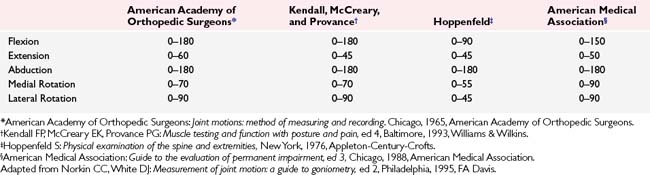

Even more important is regaining normal arthrokinematic motions at the shoulder. Active shoulder range of motion is always gathered before passive motions (Manske and Stovak 2006). Active shoulder ROM is seen in Table 3-3 (Manske and Stovak 2006). Many times, gross overall shoulder motion may only appear to be slightly limited, whereas arthrokinematic motion is drastically dysfunctional. For example, it is not uncommon for a patient to have full glenohumeral motion, yet impinge as a result of altered scapulohumeral motion from a restricted inferior or posterior shoulder capsule creating obligate humeral translations.

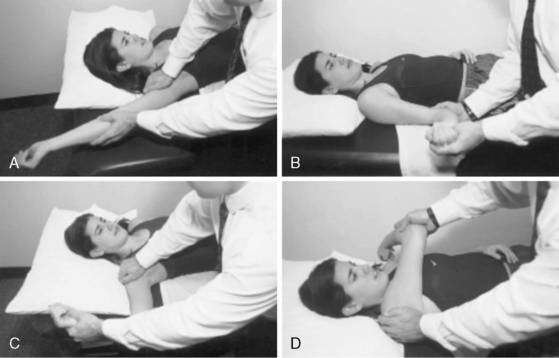

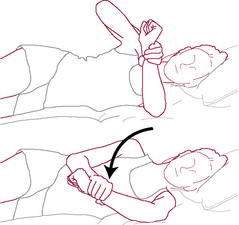

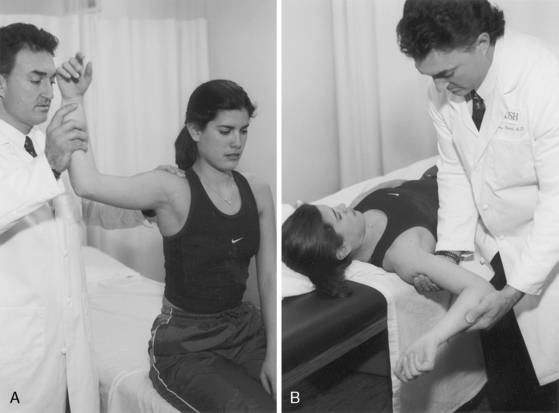

Therefore, it is imperative to also ensure evaluation of isolated glenohumeral motions is performed. One of the more common problematic limited motions with a variety of shoulder conditions is that of the posterior or inferior shoulder structures. Debate continues as to whether this is a result of capsular or other soft tissues. Regardless, it becomes an issue whenever elevation of the glenohumeral joint is required because it may increase the risk of impingement. Assessment of the posterior shoulder can be done by measuring isolated glenohumeral internal rotation. To perform this test the humerus is taken into passive internal rotation while the scapular is stabilized by grasping the coracoid process and the spine and monitoring for movement (Fig. 3-6). When passive slack from the posterior shoulder is taken up, the humerus will no longer internally rotate or resistance to movement will allow the scapula to tilt forward. When motion is detected or internal rotation has ceased, the examiner measures isolated glenohumeral internal rotation. Wilk et al. (2009) have shown this to be moderately reliable, whereas Manske et al. using the same technique have proved excellent test–retest reliability (Manske et al. 2010). This motion should be compared bilaterally to assess for a deficit between involved and uninvolved shoulders. A difference of greater than 20 degrees of internal rotation is thought to be a precursor to shoulder pathology. Loss of shoulder internal rotation is not always pathologic because some of this motion may be lost as a result of bony changes in the humerus. The concept of total shoulder rotation ROM should also be mentioned. By adding the two numbers of GH internal rotation and external rotation together, a composite of total shoulder motion can be obtained (Fig. 3-7). Ellenbecker et al. (2002), measuring bilateral total rotation range of motion in professional baseball and elite junior tennis players, found that although a dominant arm may show increased external rotation and less internal rotation, the total ROM was not significantly different when comparing the two shoulders. Therefore, one needs to not only address the internal rotation loss, but also should ensure that the total range of motion is not limited. Using normative data from population specific research can assist the therapist in interpreting normal range of motion patterns and identify when sport-specific adaptations or clinically significant adaptations are present (Ellenbecker 2004).

Figure 3-6 Assessment of the posterior shoulder performed by measuring isolated glenohumeral internal rotation.

Figure 3-7 Total rotation range of motion concept.

(Redrawn from Ellenbecker TS. Clinical Examination of the Shoulder. Saunders, St. Louis, 2004, p. 54.)

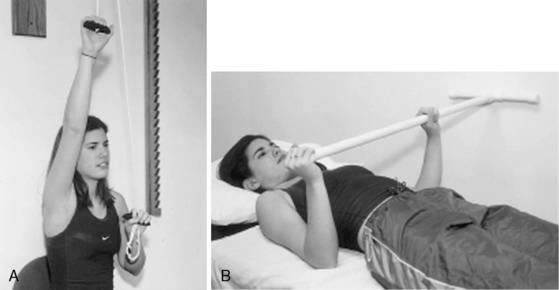

Once active motion can be initiated, the patient is encouraged to work early on pain-free ranges below 90 degrees of elevation. For most patients an early goal is 90 degrees of forward flexion and approximately 45 degrees of external rotation with the arm at the side. For surgical patients, it is the responsibility of the surgeon to obtain at least 90 degrees of stable elevation in the operating room for the therapist to be able to gain this same motion after surgery. At this point in rehabilitation, methods to gain motion include active-assisted range of motion with wands or pulleys, passive joint mobilization, and passive stretching exercises (Figs. 3-8 and 3-9).

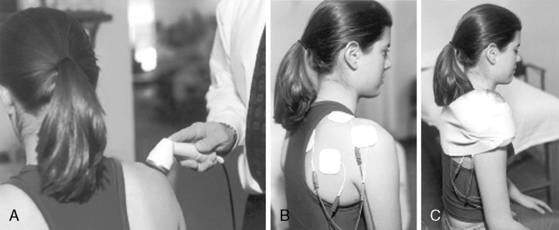

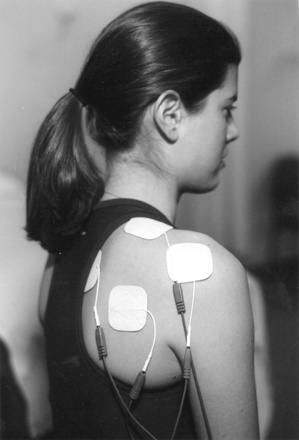

Pain Relief

Both shoulder motion and strength can be inhibited by pain and swelling, with pain being the major deterrent. Pain can be the result of the initial injury or from surgical procedures attempting to repair/replace the injured tissue. Pain relief can be achieved by a variety of modalities including rest, avoidance of painful motions (e.g., immobilization; Fig. 3-10), cryotherapy, ultrasound, galvanic stimulation, and oral or injectable medications (Fig 3-11). Previous literature substantiates that continuous cryotherapy following surgical procedures results in immediate and continued cooling of both subacromial space and glenohumeral joint temperatures (Osbahr et al. 2002) and decreases the severity and frequency of pain, which allows more normal sleep patterns and increases overall postoperative shoulder surgery comfort and satisfaction (Singh et al. 2001, Speer et al. 1996).

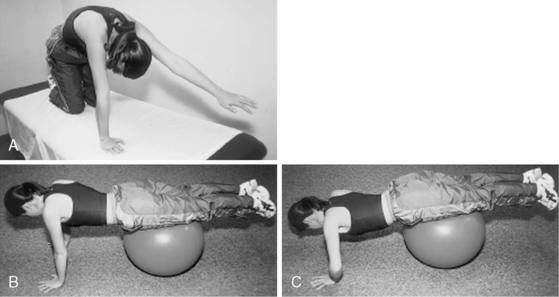

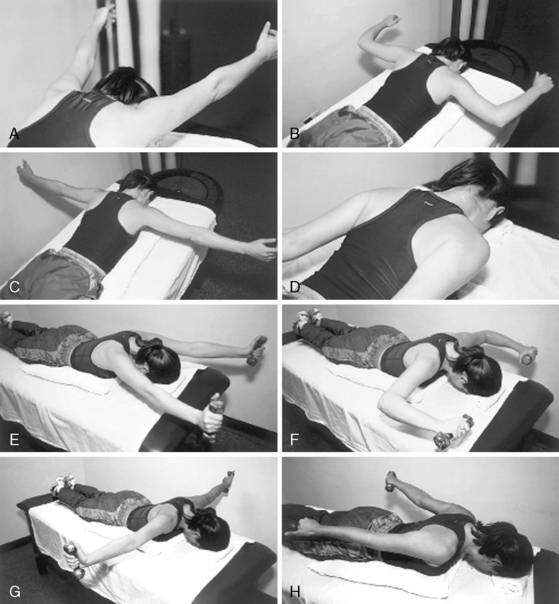

Muscle Strengthening

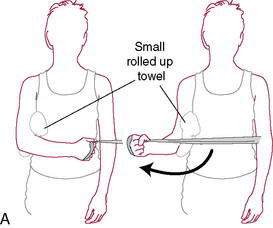

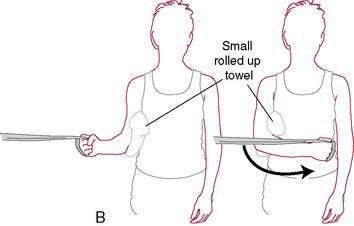

Appropriate timing for initiation of muscle strengthening exercises during shoulder rehabilitation is completely dependent on the diagnosis. A simple uncomplicated impingement syndrome may be able to commence strengthening exercises on day 1, whereas a postoperative rotator cuff repair may require up to 10 weeks before initiation of strengthening of the cuff, allowing the repaired tendon time to heal securely to bone of the greater tuberosity. Strengthening of the muscles around the shoulder can be accomplished through different exercises. Basic safe exercises include isometrics (Fig. 3-12), and closed kinetic chain exercises (Figs. 3-13 and 3-14). The advantage of closed chain exercises is a co-contraction of both the agonist and the antagonist muscle groups that help enhance stability of the glenohumeral joint. This co-contraction closely replicates normal physiologic motor patterns and function to help stabilize the shoulder and limit abnormal and potentially destructive shear forces crossing the glenohumeral joint. A closed chain exercise for the upper extremity is one in which the distal segment is stabilized against a fixed object. During shoulder exercises this stable object may be a wall, door, table, or floor. One example of a closed-kinetic-chain exercise used in an elevated, more functional position is the “clock” exercise in which the hand is stabilized against a wall or table (depending on the amount of elevation allowed) and the hand is rotated to different positions of the clock face (Fig. 3-13). This is done by creating an isometric contraction in the direction of the numbers around the clock face. Alternatively, the therapist can also give manual resistance in the same directions to the patient’s arm as they are stabilizing it by holding on to the wall (Fig. 3-14). These motions are thought to effectively stimulate rotator cuff activity. Initially, the maneuvers are done with the shoulder in less than 90 degrees of abduction or flexion. As healing tissues improve and motion is recovered, strengthening progresses to greater amounts of abduction and forward flexion.

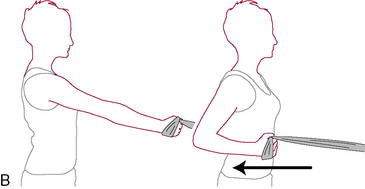

Isometric exercises can also be performed in various ranges of shoulder elevation. It is easiest to do this with the patient in supine. The “balance position” is that of 90 to 100 degrees of forward flexion of the shoulder while supine (Fig. 3-15). This position requires little activation of the deltoid so that the rotator cuff can be worked without provoking a painful shoulder response. In this position a contraction from the deltoid will result in joint compression, helping to enhance joint stability. Rhythmic stabilization or alternating isometric exercises can be performed very comfortably in the supine position and can be done for both rotator cuff and shoulder muscles.

Figure 3-15 The “balance position” is that of 90 to 100 degrees of forward flexion of the shoulder while supine.

Strengthening of scapular stabilizers is important early on in the rehabilitation program. Scapular strengthening can begin in side lying with isometrics or isotonics or closed chain (Fig. 3-16) and progress to open-kinetic-chain exercises (Fig. 3-17).

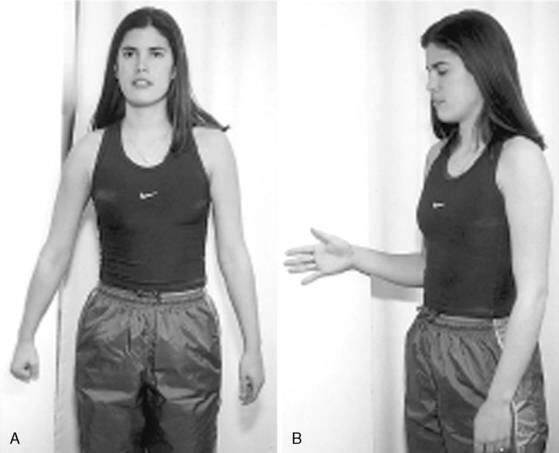

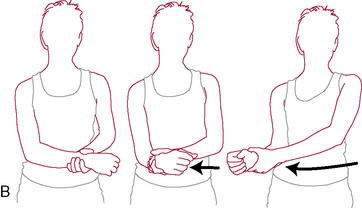

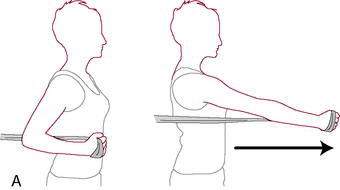

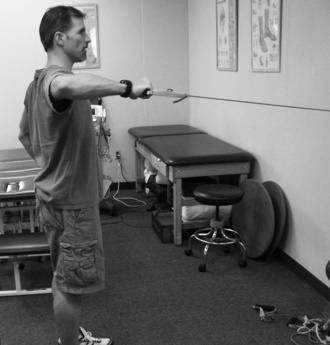

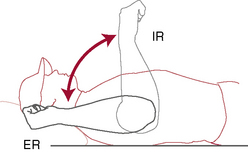

As the patient progresses, more aggressive strengthening can be instituted by moving from isometric and closed-chain exercises to those that are more isotonic and open chain in nature (Fig. 3-18). Open chain exercises are done with the distal end of the extremity no longer stabilized against a fixed object. This results in the potential for increased shear forces across the glenohumeral joint. Shoulder internal and external rotation exercises are done initially standing or seated with the shoulder in the scapular plane. The scapular plane position is recreated with the shoulder between 30 degrees and 60 degrees anterior to the frontal plane of the thorax, or halfway between directly in front (sagittal plane) and directly to the side (frontal plane). The scapular plane is a much more comfortable plane to exercise in because it puts less stress on the joint capsule and orients the shoulder in a position that more closely represents functional movement patterns. Rotational exercises should begin with the arm comfortably at the patient’s side and advance to 90 degrees based on the patient’s injury, level of discomfort, and stage of soft tissue healing. The variation in position positively stresses the dynamic stabilizers by altering the stability of the GH joint from maximum stability with the arm at the side to minimum stability with the arm in 90 degrees of abduction.

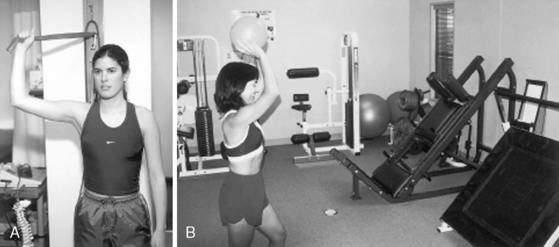

For those who participate in either competitive or recreational overhead sporting activities, the most functional of all open-chain exercises are plyometric exercises. Plyometric activities are defined by a stretch-shortening cycle of the muscle tendon unit. This is a component of almost all athletic activities. Initially the muscle is eccentrically stretched and loaded. Following the stretched position the shoulder/arm quickly performs a concentric contraction. These forms of exercises are higher level exercises that should only be included once the patient has developed an adequate strength base and achieved full ROM. Not all patients require plyometric training, and this should be discussed before their incorporation. Plyometric exercises are successful in development of strength and power. Theraband tubing, medicine ball training, or free weights are all acceptable plyometric devices for the shoulder (Fig. 3-19).

Rotator Cuff Tendinitis in the Overhead Athlete

Michael J. O’Brien, MD, and Felix H. Savoie III, MD

Anatomy and Biomechanics

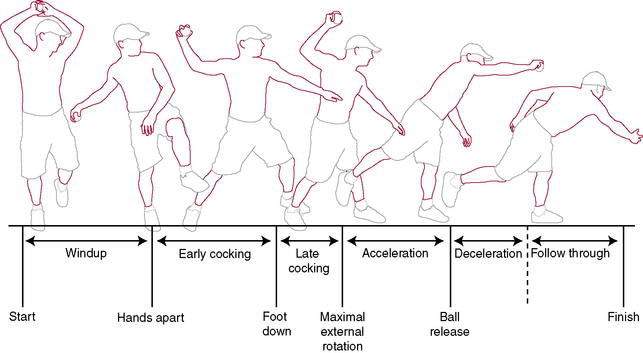

The Throwing Cycle

The baseball pitch serves as the biomechanical model for many overhead throwing motions. The throwing cycle is a kinetic chain that derives energy from the lower extremities, transfers it through the pelvis and trunk rotation, and releases that energy through the upper extremity. The arm positions and motions of the throwing cycle serve as a good model for examination of rotator cuff function in overhead athletes. The throwing motion and its biomechanics have been divided into six stages: wind-up, early-cocking, late-cocking, acceleration, deceleration, and follow-through (Fig. 3-20).

Pathogenesis

Injury to the shoulder during the throwing cycle is thought to occur during the late-cocking phase, when the shoulder is in extreme external rotation and horizontal abduction. Abnormal motion of the humeral head relative to the glenoid can injure the superior and posterosuperior labrum and glenoid and the undersurface of the rotator cuff. This phenomenon has been called internal impingement of the shoulder or posterior superior glenoid impingement (Burkhart et al. 2003, Fleising et al. 1995, Jobe 1995, Kelly and Leggin 1999). Several factors have been implicated in the development of internal impingement, including traction on the biceps tendon, laxity of the anterior band of the inferior glenohumeral ligament caused by excessive external rotation, posterior capsular tightness, and scapular dyskinesia.

Grossman et al. (2005) quantified glenohumeral motion following external rotation capsular stretch and subsequent posterior capsular shift to simulate a posterior capsular contracture in the thrower’s shoulder. In maximal external rotation in intact specimens, the humeral head moved in a posterior and inferior direction. A posterior capsular shift was performed to simulate posterior capsular contracture. Following posterior capsular shift, there was a trend toward a more superior position of the humeral head in maximal external rotation. Posterior capsular contracture causes a similar result as the head is pushed anterior–superior into the coracoacromial arch during flexion. Superior translation allows the head to migrate closer to the acromion, and an increase in the force transmitted to the rotator cuff results as the cuff is pressed between the humeral head and the overlying coracoacromial arch. The increased pressure on the cuff can lead to degradation and damage over time.

History and Physical Examination

Physical examination of the overhead athlete requires a global evaluation.

The physical examination of the shoulder and upper extremity should always begin with inspection.

Active and passive range of motion (PROM) should be assessed and compared to the contralateral side. The American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons have recommended four functional ranges of motion that should be measured (Richards et al. 1994): forward elevation, internal rotation, and external rotation at the side and at 90 degrees of abduction are measured. Loss of the total arc of rotation, specifically with internal rotation, is a common finding in the glenohumeral joint of the injured pitcher (Burkhart et al. 2003). This loss is likely secondary to tightness of the posterior soft tissues, including the posterior rotator cuff and capsule.

Imaging

Radiographs

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Management

Frequently, rotator cuff tendinitis in the overhead athlete can be successfully treated with a well-structured and carefully implemented nonoperative rehabilitation program (Rehabilitation Protocol 3-1). Rehabilitation follows a multiphase approach with emphasis on controlling inflammation, restoring muscle balance, improving soft tissue flexibility, enhancing proprioception and neuromuscular control, and efficiently returning the athlete to competitive throwing (Wilk et al. 2002). Treatment should focus on restoration of sound mechanics during the throwing cycle, core muscle strengthening of the trunk and lower extremities, and strengthening of periscapular stabilizers.

REHABILITATION PROTOCOL 3-1 Rehabilitation for Rotator Cuff Tendinitis in Overhead Athletes

Phase I

Phase II

Phase III

Phase IV

Rotator Cuff Repair

Robert C. Manske, PT, DPT, SCS, MEd, ATC, CSCS

Rotator cuff tears and subacromial impingement are among the most common causes of shoulder pain and disability. Lewis reports a lifetime risk of up to 30% and an annual risk of at least one episode to reach 50% (Lewis 2008). The frequency of rotator cuff tears increases with age and full-thickness tears are uncommon in patients younger than 40 years of age. However, the incidence of tears in the elderly dramatically increases as evidenced by rotator cuff tear in 33% of shoulders in the 50- to 60-year range and in 100% in those more than 70 years of age reported in cadavers (Lehman et al. 1995). Recently evidence has shown that there may also be a genetic predisposition to rotator cuff injuries because full-thickness tears in siblings have been shown to be more likely to progress over a period of 5 years compared to a control group (Gwilym et al. 2009).

The rotator cuff complex refers to the tendons of four muscles: the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor. The four muscles originate on the scapula, cross the glenohumeral joint, then transition to tendons that insert onto the tuberosities of the proximal humerus. The term “rotator cuff” may be a misnomer because the most important function of the rotator cuff may be that of compression (Chepeha 2009). The rotator cuff has three well-recognized functions: rotation of the humeral head, stabilization of the humeral head in the glenoid socket by compressing the round head into the shallow socket, and the ability to provide “muscular balance,” stabilizing the glenohumeral (GH) joint when other larger muscles crossing the shoulder contract.

Rotator cuff tears can be classified as either acute or chronic based on their timing. Additional classification can include the amount of tear as either partial (bursal or articular side tears) or complete. Tears can also be described as either traumatic or degenerative (Table 3-4). Complete tears can be classified based on the size of the tear in square centimeters as described by Post (1983) (Table 3-5). All of these factors, as well as the patient’s demographic and medical background, play a role in determining a treatment plan.

| Partial-thickness tears |

| Full-thickness tears |

| Acute tears |

| Chronic tears |

| Traumatic tears |

| Degenerative tears |

| Name | Centimeters |

| Small | (0–1 cm2) |

| Medium | (1–3 cm2) |

| Large | (3–5 cm2) |

| Massive | (>5 cm2) |

Regardless of the surgical technique used, treatment goals of rotator cuff repair have not significantly changed over the years. Goals following rotator cuff repair can be seen in Table 3-6. These goals can be met using an evidence-based, progressive therapy program. For purposes of this section several different protocols are described, including those for (1) partial to small tears, (2) medium to large tears, and (3) massive tears.

Table 3-6 Treatment Goals Following Rotator Cuff Repair

| Goals |

| Pain relief |

| Improve range of motion |

| Improve strength |

| Improve function |

| Return to previous function |

Type of Repair

Management of rotator cuff tendon tears continues to be a challenge. Few surgeons will still perform open repairs, especially in patients with anterior deltoid detachment for fear of postoperative deltoid avulsion (Gumina et al. 2008; Hata et al. 2004; Sher et al. 1997). Patients who have had a deltoid muscle detachment or release from the acromion or clavicle (e.g., traditional open rotator cuff repair) may not perform active muscle contractions of the deltoid for up to approximately 8 weeks following surgery. This is done to avoid the horrible outcome of an avulsion of the deltoid muscle. Typically three types of procedures are described with the open procedure being the oldest as it was described almost 100 years ago (Codman 1911). Next in line was the advancement of the mini-open procedure that utilizes a much smaller incision. Most recently all arthroscopic procedures have become popular. These three procedures can be thought of as an evolution or transition to newer and better techniques as biomechanics of surgery and soft tissue healing have been advanced with increasing amounts of scientific knowledge.

The open rotator cuff repair is very conservative compared to mini-open or arthroscopic repair procedures due to detachment of the deltoid. Because of the lack of use of this older procedure, a formal rehabilitation approach will not be described other than to say that active motion is not allowed until after 8 to 12 weeks depending on tissue quality and ability to reattach the required tendons. Actual gentle strengthening is not begun until after about 12 weeks at minimum. Patients are usually not even able to comfortably elevate above shoulder level before 6 months (Hawkins 1990; 1999).

The mini-open technique involves a small (less than 3 cm) vertical split with the orientation of the deltoid fibers, allowing mild, early deltoid muscle contractions. The mini-open technique is popular because it does not create the surgical morbidity of the open technique. The deltoid muscle is not taken down from the acromion so rehabilitation is progressed somewhat faster. Additionally, with the mini-open technique, transosseous fixation, which may lead to better footprint restoration, can be used. The downfalls to the mini-open include an increased incidence of stiffness (11%–20%) compared to an all arthroscopic technique (Nottage 2001; Yamaguchi et al. 2001).

Tear Pattern

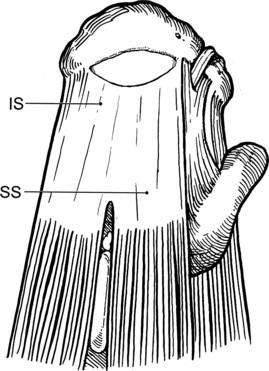

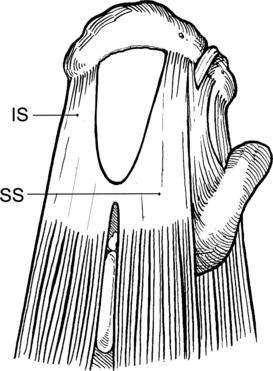

Lo and Burkhart (2003) have described four main types of tear patterns, and these include crescent-shaped tears, U-shaped tears, L-shaped and reverse L-shaped tears, and massive tears. Understanding of and recognition of the tear pattern is the first step in determining appropriate surgical treatment.

Crescent-shaped tears (Fig. 3-21). These are usually the easiest to repair. These tears rarely have a substantial amount of medial retraction; therefore, they are usually easily mobilized and able to be secured to the tuberosity without excessive tension placed upon them.

Figure 3-21 Crescent-shaped tear.

(From Miller MD, Sekiya JK. Sports Medicine. Core Knowledge in Orthopaedics. St. Louis, Mosby, 2006, pg. 305, fig. 36-17A.)

U-shaped tears (Fig. 3-22). These tears look like an extension of the crescent-shaped tear pattern that have retracted further medially. A large margin convergence is needed to secure this tear. Using a margin convergence procedure, the anterior and posterior edges of the tear are sutured back together so that the lateral edge can be more easily brought back to the greater tubercle.

Figure 3-22 U-shaped tear.

(From Miller MD, Sekiya JK. Sports Medicine. Core Knowledge in Orthopaedics. St. Louis, Mosby, 2006, pg. 306, fig. 36-17B.)

L-shaped and reverse L-shaped tears (Fig. 3-23). This tear pattern involves a tendon tear from the tuberosity with an additional longitudinal split posterior or anteriorly involving a portion being retracted.

Size of the Tear

Functional outcome and expectations after rotator cuff repair are directly related to the size of the tear repaired. Numerous authors have reported age and tear size to be significant factors in healing after rotator cuff repair (Bigliani et al. 1992; Boileau et al. 2005; Cole et al. 2007; Gazielly et al. 1994; Harryman et al. 1991; Nho et al. 2009).

Onset of Rotator Cuff Tear and Timing of the Repair

Acute tears with early repair may have a slightly greater propensity to develop stiffness, and a little more aggression in early ROM programs has proven beneficial. Cofield et al. (2001) noted that patients who underwent an early repair progressed more rapidly with rehabilitation than those with a late repair. It has been shown that early intervention of a single-tendon tear may optimize healing and not allow progression to a multiple-tendon tear (Nho et al. 2009).

Patient Variables

Several authors have reported a less successful outcome in older patients than young. This may be because of older patients typically having larger and more complex tears, probably affecting outcomes. Age and tear size are significant factors in tendon healing capabilities (Bigliani et al. 1992; Boileau et al. 2005; Cole et al. 2007; Constant and Murley 1987; Gazielly et al. 1994).

Multiple other authors agree that workers’ compensations patients tend to progress slower or have less than optimal return of function (Abboud et al. 2006; Bayne and Bateman 1984; McLaughlin and Asherman 1951; Hawkins et al. 1999; Iannotti et al. 1996; Misamore et al. 1995; Paulos and Kody 1994; Shinners et al. 2002; Smith et al. 2000). Kolgonen, Chong, and Yip (2007) found a strong association between workers’ compensation patients and poor outcomes after multiple shoulder surgeries.

Finally, researchers have noted a correlation between preoperative shoulder function and outcomes after surgical repair. Generally, patients who have an active lifestyle before surgery return to the same postoperatively. Furthermore, Henn et al. (2007) assessed preoperative expectations with an outcomes questionnaire and found that those who had a greater preoperative expectation for their recovery had better postoperative performance on several subjective outcome measures.

Imaging

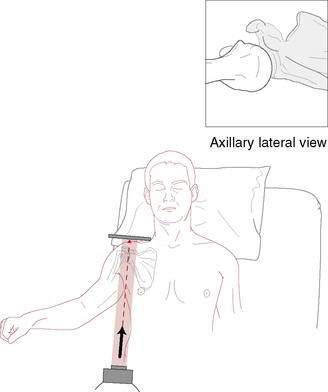

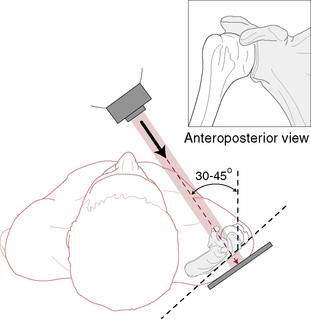

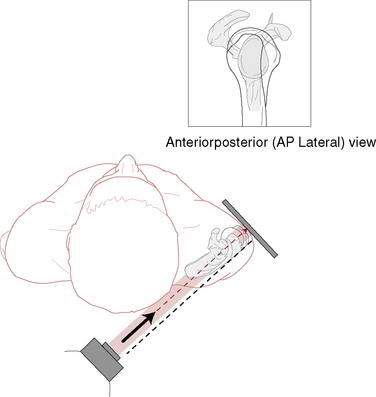

Imaging studies may be helpful in confirming the diagnosis of a chronic rotator cuff tear and may help to determine the potential success of operative treatment. A standard radiographic evaluation or “trauma shoulder series” should be obtained, including an anteroposterior (AP) view in the plane of the scapula (“true AP” of GH joint) (Fig. 3-24), a lateral view in the plane of the scapula (Fig. 3-25), and an axillary lateral view (Fig. 3-26). This may also show some proximal (superior) humeral migration, indicative of chronic rotator cuff insufficiency. Plain film radiographs can also show degenerative conditions or bone collapse consistent with a cuff tear arthropathy in which both the cuff deficiency and the arthritis contribute to the patient’s symptoms. These radiographs help to eliminate other potential pathologic entities such as a fracture or dislocation.

(Redrawn from Rockwood CA Jr, Matsen FA III. The Shoulder, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1988.)

Figure 3-25 Radiographic evaluation of the shoulder; lateral view in the plane of the scapula.

(Redrawn from Rockwood CA Jr, Matsen FA III: The Shoulder, 2nd ed. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1988.)

Examination

A subacromial injection of lidocaine may help to differentiate weakness that is caused by associated painful inflammation from that caused by a cuff tendon tear. Additionally, provocative maneuvers including the Neer impingement sign (Fig. 3-27) and the Hawkins sign (Fig. 3-28) may be positive with other conditions such as rotator cuff tendinitis, bursitis, or partial-thickness rotator cuff tears.

Treatment

Chronic Tears

Chronic rotator cuff tears may be an asymptomatic pathologic condition that has an association with the normal aging process. A variety of factors, including poor vascularity, a “hostile” environment between the coracoacromial arch and the proximal humerus, decreased use, or gradual deterioration in the tendon, contribute to the senescence of the rotator cuff, especially the supraspinatus. Lehman and colleagues (1995) found rotator cuff tears in 30% of cadavers older than 60 years and in only 6% of those younger than 60 years of age. Many patients with chronic rotator cuff tears are over the age of 50 years, have no history of shoulder trauma, and have vague complaints of intermittent shoulder pain that has become progressively more symptomatic. These patients may also have a history that is indicative of a primary impingement etiology.

Rotator cuff rehabilitation continues to evolve as the science of tendon/cuff healing continues to grow. As a result of stronger surgical fixation methods with minimal deltoid involvement, a slightly more aggressive shift has been followed for the last few years. Despite this, most protocols are based on empiric clinical experience. Because results of revision rotator cuff repairs are typically inferior to those of primary repairs, it is important to avoid active motion and resistance exercises too early (Lo and Burkhart 2004). This creates the “rotator cuff paradox” in which a too conservative approach will lead to stiffness, whereas a too aggressive approach can lead to recurrent tearing. Therefore optimal treatment, although not clearly established with high levels of evidence, requires careful judgment regarding progression and a delicate balance of motion and strengthening that must be customized to each patient.

Rehabilitation Protocol

Actual protocols for various tear sizes (partial tears/small; medium/large; massive) are seen in Rehabilitation Protocols 3-2, 3-3, and 3-4. Although protocols exist for open procedures, the protocols described herein will be for all arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs due to advancement in surgical technique. All protocols have similar outlines with four phases but are adjusted according to tear size. Clinicians should take into consideration all other comorbidities and risk factors related to postoperative stiffness.

REHABILITATION PROTOCOL 3-2 Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair Protocol for Partial-Thickness Tear and Small Full-Thickness Tears

Phase I: Immediate Post Surgical Phase (Weeks 0–4)

Days 1 to 6

Phase II: Protection and Protected Active Motion Phase (Weeks 5–12)

Weeks 5 to 6

Phase III: Early Strengthening (Weeks 10–16)

Week 10

REHABILITATION PROTOCOL 3-3 Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair Protocol: Medium to Large Tear Size

Phase I: Immediate Post Surgical Phase (Weeks 0–6)

Days 1 to 6

Days 7 to 42

Phase II: Protection and Protected Active Motion Phase (Weeks 7–12)

Weeks 9 to 12

Phase III: Early Strengthening (Weeks 12–18)

Week 12

Week 14

REHABILITATION PROTOCOL 3-4 Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair Protocol: Massive Tear Size

Phase I: Immediate Postsurgical Phase (Weeks 0–8)

Days 1 to 14

Weeks 2 to 8

Phase II: Protection and Protected Active Motion Phase (Weeks 8–16)

Weeks 8 to 10

Weeks 10 to 16

Phase III: Early Strengthening (Weeks 16–22)

Week 16

Week 18

Sling and initiation of active ROM are seen for all repairs in Table 3-7.

| Size of Tear | Sling Use | Initiation of Active Motion |

|---|---|---|

| Partial to small (<1 cm) | 4 weeks | 4 weeks |

| Medium to large (2–4 cm) | 6 weeks | 6 weeks |

| Massive (>5 cm) | 8 weeks | 8 weeks |

Immediate Postoperative Phase

Because pain typically is elevated in this stage, cold therapy and electrical stimulation may be used to relieve discomfort. The initial position of immobilization is usually with the shoulder slightly abducted in the scapular plane, elbow flexed to 90 degrees, and shoulder internally rotated resting on an abduction pillow (see Fig. 3-10). Slight abduction as the immobilization placement does several things including allowing an increase in supraspinatus blood flow to decrease the “wringing out” or “watershed” effect that occurs with the arm in a completely adducted shoulder position. Secondly, it places the supraspinatus in a relaxed position decreasing the potential of placing excessive tension across the repair due to reflex muscular contractions.

Because limited shoulder motion following rotator cuff repair is one of the biggest complications, a reestablishment of passive motion without sacrificing repair integrity is important in this phase. Depending on repair size, passive ROM predominates in this early stage. A slower rate of motion progression is warranted for those with large or massive tears. Passive motion limitations are listed in the rehabilitation protocols. Passive pendulum exercises are beneficial and cause very little active muscular activity of the cuff. Dockery et al. (1998) and Lastayo et al. (1996) found that cuff muscle activity during pendulum exercises was not different than that during continuous passive motion (CPM) or manual therapy passive motion. Recently, Ellsworth et al. (2006) found that mean supraspinatus/upper trapezius activity during the pendulum exercise in patients with shoulder pathology was activated to 25% maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC), and it was slightly lower at 20% with a suspended weight. This is an EMG amount that approaches the upper level of what is considered minimal. Therapists should ensure the patient is performing a relaxed pendulum exercise with minimal muscle activity. Pendulums that are painful to perform are more than likely not creating the relaxing effect wanted and should therefore be discontinued at this early time. The remainder of the upper extremity joints can be treated with active assisted exercises of the elbow, hand, wrist, and cervical spine.

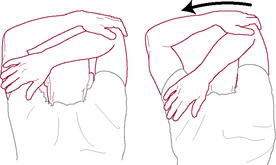

Because of the importance of scapular stabilization and function of the rotator cuff, scapular muscle isometrics and active motion can usually begin early. Early gentle setting of the scapular muscles can be done in sidelying positions with the shoulder protected (Fig. 3-29). Motions of elevation/depression and protraction/retraction are effective to isolate scapular muscle recruitment.

Recent discussions have included use of complete removal of load to repaired tendons in an effort to improve healing. Galatz et al. (2009) using an animal model applied botulinum toxin to paralyze the supraspinatus following rotator cuff repair. They used botulinum A and immobilized one group, allowed free range in another group, and finally used saline injection and casting in a control group. Complete paralysis had a negative effect on cuff healing and proved that complete removal of loads from a healing rotator cuff tendon is detrimental. A low level of controlled force is probably beneficial for tendon healing.

Passive motion predominates this phase in an attempt to decrease adhesion formation, contractures, and limitations of periarticular structures (McCann et al. 1993; Dockery et al. 1998; Lastayo et al. 1996). These passive exercises are done to decrease the risk of forming selective hypomobilities (Harryman et al. 1990). An asymmetrical tightening of the capsule with prolonged immobilization or with disuse will cause an obligate translation in the direction opposite the tight tissue constraint. After those following rotator cuff repairs, the primary tissue that becomes tight is the posterior and anterior capsule. Furthermore, Hata et al. (2001) used arthrographic comparison between patients who had and those who did not have pain following rotator cuff repair. Patients with shoulder pain after repair had reduced capacity and motion of the GH joint. The initial postoperative treatment has a direct bearing on postoperative stiffness, and failure to begin passive ROM in the first week after the operation can lead to loss of motion.

Early rehabilitation should include both physiologic and accessory joint mobilizations. Manske et al. (2010) have determined that posterior glide accessory joint mobilization techniques with passive stretching are better than passive stretching alone for treatment of posterior shoulder tightness. Surenkok (2009) has recently shown that pain was decreased and shoulder motion was improved immediately following scapular mobilizations in those with painful shoulders.

An area that is oftentimes taken too lightly is the position in which to place the shoulder while performing mobilization. In cadaver studies of strain on the supraspinatus, Zuckerman et al. (Zuckerman et al. 1991; Muraki et al. 2007; Hatakeyama et al. 2001; Hersche and Gerber 1998) all concluded that strains are significantly less when the humerus is placed in at least 30 to 45 degrees of elevation. This becomes most important about 3 weeks after repair because it is at this time that the repaired tendon is at its weakest (Ticker and Warner 1998).

Protection and Protected Active Motion Phase

Depending on tear size, immobilization can be discontinued from between 4 and 8 to 10 weeks. At this point gentle active assistive and active ROM can begin. Light isometric exercises predominate this phase also. These isotonic exercises should begin with the shoulder below 90 degrees of elevation or at 90 degrees in the “balance position.” The balance position is used so that the deltoids will not pull the humerus superior, but rather they will generate more of a compressive force as tension generated is more horizontal at 90 degrees of elevation while supine. Exercises at this point include submaximal isometrics in multiple angles. The isometric exercises can be done initially as alternating isometrics progressing to rhythmic stabilization exercises. Initially these should be done slow and controlled, allowing the patient to watch the movement patterns in a proactive state of awareness. This can be advanced to performance in a more reactive state of awareness in which the patient does not know the direction of force or is not allowed to watch the resistance given. This increases the complexity of the isometric exercise. Heavy, more significant strengthening exercises should be avoided until the advanced strengthening phase. Gentle closed kinetic chain exercises can be done to help minimize humeral shear (Ellenbecker et al. 2006; Kibler et al. 1995). More aggressive joint mobilization techniques and passive motion can be performed if ROM is not full. Emphasis of treatment of this phase should be returning full symmetrical passive ROM. Once active motion is started, the patient is not allowed to elevate the shoulder in a shrugging pattern. Starting active elevation with scapular motion rather than humeral elevation could be due to a capsular limitation or as a compensatory pattern from continued cuff weakness. If the shrug exists, exercises to regain normal scapular and glenohumeral arthrokinematics or progressive rotator cuff strengthening exercises should be continued. Motions allowed include humeral active ROM in flexion, abduction, and external and internal rotation.

Conclusion

It should always be stressed to the patient that although they may be pain free and most substantial gains will be seen in the first 6 months, full unrestricted return to activity and full potential will not be achieved until about 1 full year (Matson et al. 2004; Rokito 1996). Rotator cuff rehabilitation is a long and slow process!

Shoulder Instability Treatment and Rehabilitation

Introduction

Glenohumeral instability is a relatively common orthopaedic problem, encompassing a wide spectrum of pathological mobility at the shoulder joint ranging from symptomatic laxity to frank dislocation. The glenohumeral joint allows greater mobility than any other joint in the human body; however, this comes at the expense of stability. Perhaps more so than other joints, shoulder stability is predicated on adequate soft tissue (muscular and ligamentous) function and integrity, rather than bony congruity and alignment. Instability of the joint can easily result from impairments or imbalances in muscle function, ligamentous laxity, and/or bony abnormalities. Given this inherent laxity, it is not surprising that there is a relatively high incidence of instability events. A Danish registry study suggested a 1.7% overall incidence rate for the population as a whole (Hovelius et al 1996). Young, athletic populations are at even higher risk, with a study of cadets at the United States Military Academy demonstrating an overall incidence of shoulder instability of 2.8%. In this population, trauma was identified as the most common etiology, with more than 85% of patients reporting antecedent trauma. More than 90% of shoulder dislocations are in the anterior direction, particularly because the position of combined external rotation and abduction, common in many contact sports, places the shoulder in an extremely vulnerable position. Most concerning regarding first-time shoulder dislocations is the high recurrence rate, which has been reported as between 20% and 50% and as high as 90% in young patients. These epidemiologic findings highlight the importance of accurately identifying and appropriately treating shoulder instability. There is still, however, considerable controversy concerning appropriate treatment algorithms for shoulder instability. Prior to deciding on an appropriate treatment course, factors including patient age, type of activity/sport, activity/sport level, goals, and likelihood of compliance must be considered. In addition, the mechanism of injury and the type of damage incurred, which may include labral, capsule, biceps, and/or rotator cuff lesions, in addition to bony avulsions, will influence the most appropriate course of treatment for the patient.

Anatomic Considerations

The range of motion permitted at the glenohumeral joint is a consequence of minimal bony constraint provided by the humeral head and glenoid articulation. The glenoid fossa is a shallow structure, covering only 25% of the humeral head surface. Stability in the joint is therefore primarily a consequence of its static and dynamic stabilizers. The static stabilizers consist of the bony anatomy, the glenoid labrum, and capsular and ligamentous complexes and are typically only improved with surgical intervention once injured. Of note, the superior, middle, and inferior glenohumeral ligaments (SGHL, MGHL, IGHL) are especially important structures with regard to shoulder instability and thus have major implications with regard to rehabilitation following injury and/or surgery (Fig. 3-30). Specifically, the SGHL (along with the coracohumeral ligament) and MGHL are important stabilizers with regard to limiting external rotation of the adducted arm (when the arm is at the side). The IGHL is especially important in preventing anterior translation of the shoulder when in the provocative position of abduction and external rotation. The dynamic stabilizers, including the rotator cuff muscles and long head of the biceps tendon, can often be improved with an appropriate nonoperative rehabilitation program after an instability event. In fact, proper strengthening of the rotator cuff musculature and scapular stabilizers are critical components of any rehabilitation protocol, including those for nonoperative management of shoulder instability and part of the rehabilitation following surgery.

Diagnostic Evaluation: History, Physical Examination, and Imaging

Physical Examination

Imaging Studies

Finally, radiographs can be extremely helpful in the evaluation of shoulder instability. Generally, a series of radiographs including a true AP, scapular Y, and axillary view will provide significant information. Additionally, a Stryker notch view is helpful for evaluating Hill-Sachs lesions (bony injury of the humeral head from anterior dislocation), whereas the West Point view may be utilized to determine glenoid bone loss. Advanced imaging may be helpful, especially in evaluating an unstable but reduced shoulder. Computed tomography (CT) scanning is useful in evaluating glenoid hypoplasia, fracture, glenoid and humeral bone loss, and retroversion. MRI is useful in visualizing the integrity of soft tissue structures, allowing an assessment of the capsulolabral structures, the rotator cuff, the rotator interval, and the tendon of the long head of the biceps (Fig. 3-33).

Treatment Options

Nonoperative Treatment and Rehabilitation

Nonoperative treatment protocols typically consist of immobilization followed by rehabilitation with an experienced physical therapist. Traditionally, following anterior dislocation, the arm is most commonly immobilized in internal rotation to avoid the vulnerable and susceptible position of external rotation and abduction. However, recent studies have suggested little to no benefit to this immobilization, considering it as much a source of comfort as actual protection and stability. In fact, Itoi et al. (2007) suggested there actually may be some benefit to immobilizing the injured arm in a position of external rotation instead. The rationale for placement of the arm in external rotation centers on the fact that the Bankart lesion is forced to separate from the glenoid when the arm is placed in internal rotation, which may be detrimental to healing. In contrast, the authors describe how placing the arm in external rotation approximates the lesion to its correct anatomic position, allowing for a better healing process.

The nonoperative treatment options for anterior, posterior, and multidirectional glenohumeral instability all center on the same core issues. The immediate goals are to decrease pain and edema, protect the static stabilizers, and strengthen the dynamic stabilizers. The ultimate aim is to increase overall shoulder stability, which is facilitated via exercises designed to enhance joint proprioception and address kinetic chain deficits. With specific regard to posterior dislocations, recommendations have typically revolved around immobilization of the arm in external rotation and slight extension. More recently, however, Edwards et al. (2002) suggested that immobilization in internal rotation may be more appropriate, although this has yet to be fully studied.

Special Considerations

Postoperative Treatment and Rehabilitation

Anterior Instability

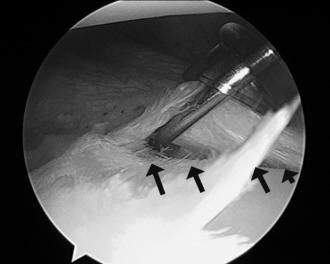

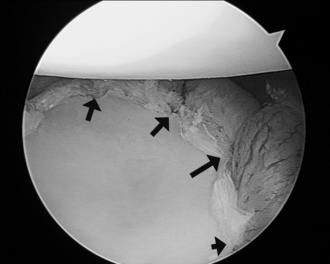

The open Bankart repair was once considered the gold standard in the treatment of anterior shoulder instability; however, proper patient selection combined with improvements in arthroscopic techniques and devices have allowed for postoperative results rivaling those of open stabilization. In the open procedure, the labrum is anatomically reduced and repaired to the anterior glenoid. Given the common coexistence of capsular injury and stretch, a concomitant capsular shift procedure is often performed. Various methods for the capsular shift have been described; the essential underlying goal is to repair the injured anteroinferior capsule and labral repair. Recurrence rate for open repair has been reported to be approximately 4%. As mentioned, both of these procedures are now increasingly performed arthroscopically (Figs. 3-34, 3-35). Although initial reports described a higher recurrence rate after arthroscopic repair, recent studies have shown that recurrence rates are nearly comparable to open repair, especially in those patients without significant glenoid bone loss or other structural abnormalities.

Figure 3-35 The patient from Figure 3-34 after repair with four anchors and suture construct (capsulolabral repair). The anchors are located at the black arrows.

See Rehabilitation Protocols 3-5 through 3-8 for specific rehabilitation programs.

REHABILITATION PROTOCOL 3-5 Nonoperative Management of Anterior Shoulder Instability

Phase I: Weeks 0–2

Phase II: Weeks 3–4

Exercises

Phase III: Weeks 4–8

Criteria for Progression to Phase III

Exercises

Exercises are performed through an arc of 45 degrees in each of the five planes of motion.

Phase IV: Weeks 8–12

Criteria for Progression to Phase IV

Figure 3-101 Active assisted and passive bar exercises are safe to perform early, especially in the supine position.

REHABILITATION PROTOCOL 3-6 Following an Arthroscopic Anterior Surgical Stabilization Procedure

Phase I: Weeks 0–4

Shoulder Motion

Phase II: Weeks 4–8

Exercises

Rotator cuff (Figs. 3-108 through 3-111) and scapular stabilizers strengthening (Figs. 3-102 through 3-105) and Theraband exercises.

Phase III: Weeks 8–12

REHABILITATION PROTOCOL 3-7 Postoperative Rehabilitation After Open (Bankart) Anterior Capsulolabral Reconstruction