Shoulder

Standard radiographs

Shoulder injury:

▪ The AP view is standard in all departments.

▪ The precise second view will vary.

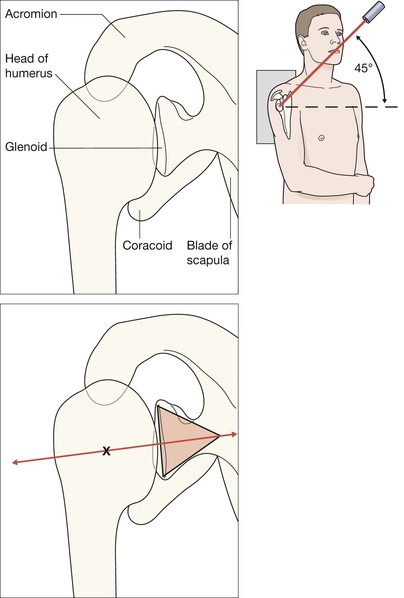

□ We prefer the apical oblique projection (aka Modified Trauma Axial, MTA; see p. 76), because it allows gentle positioning of the patient, provides excellent demonstration of dislocations and shows fractures extremely well1,2.

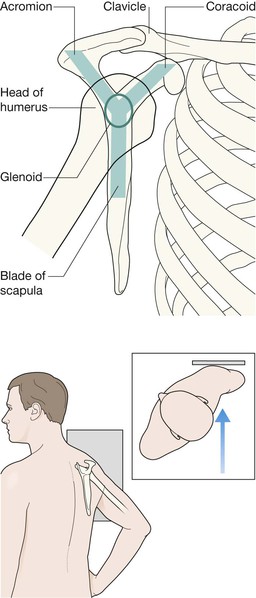

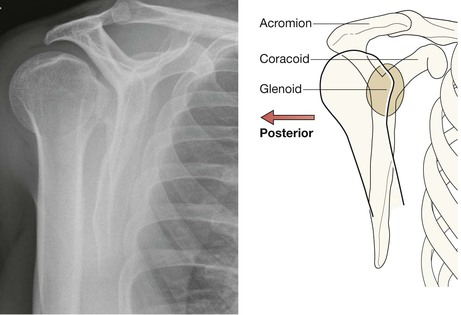

□ Second best: the scapula Y lateral (see p. 77). The patient is comfortable as the arm is not moved, and a true scapula Y lateral will show posterior dislocations3. But this view must be technically very precise, and fractures can be difficult to identify.

Suspected fracture of the clavicle:

Note our descriptive emphasis in this chapter

We are strong advocates that the second view for an injured shoulder should be the apical oblique radiograph rather than any alternative second view. Consequently, our descriptions concentrate mainly on the AP view and the apical oblique view of the injured shoulder.

Analysis: the checklists

The AP radiograph

Ask yourself five questions.

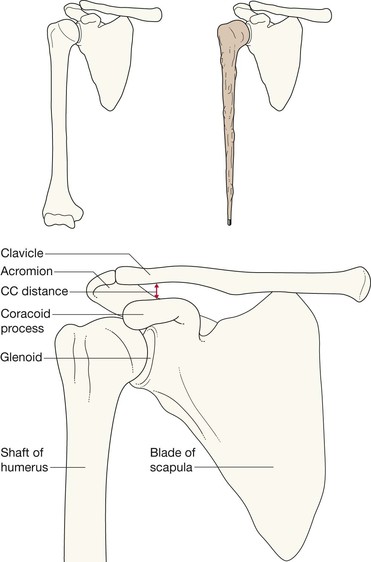

1. Is the humeral head lying directly below the coracoid process?

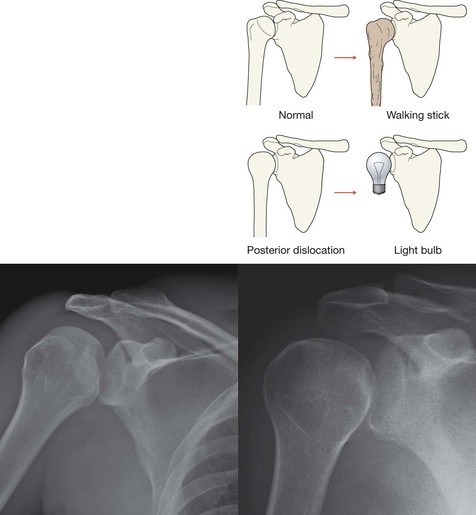

2. Does the humeral head have a walking stick shape, and does its articular surface parallel the glenoid margin?

No = use the second view to rule out a posterior dislocation.

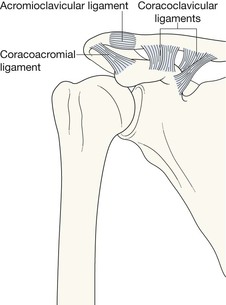

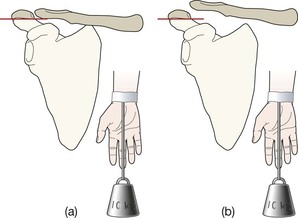

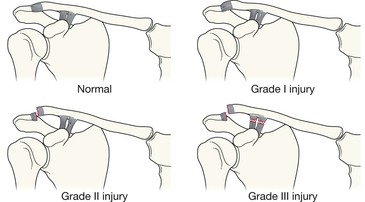

3. Is the acromioclavicular joint normal—ie do the inferior cortices of the clavicle and acromion process align?

No = subluxation or dislocation at the acromioclavicular joint.

4. Is the coracoclavicular distance more than 1.3 cm?

Yes = stretching or rupture of the coracoclavicular ligaments (see p. 86).

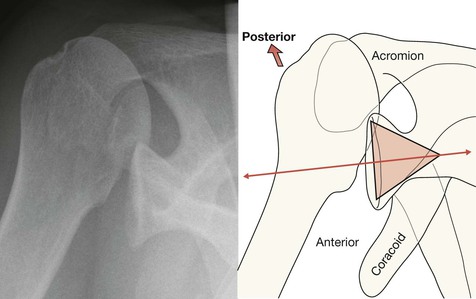

Apical oblique view1,2

Ask yourself three questions.

1. Do the articular surfaces of humerus and glenoid lie immediately adjacent to each other—ie does the centre of the triangle base line up with the centre of the glenoid articular surface?

No = a glenohumeral joint dislocation or subluxation.

2. Is there a fracture of the head or the neck of the humerus?

The common fractures4–9

Greater tuberosity of the humerus

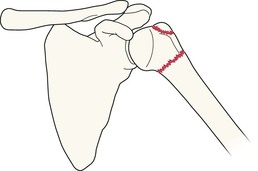

Clavicle

Accounts for 35% of all fractures involving the shoulder region6.

▪ In young children, a Greenstick fracture may occur (pp. 18–19), and appears as a slight kink in the bone.

The common dislocations4,8,9

Anterior dislocation of the glenohumeral (GH) joint

GH dislocations are the commonest traumatic dislocations of the skeleton. Anterior dislocations represent 95% of all GH dislocations. The appearances shown here are characteristic and on the whole the diagnosis is straightforward.

Anterior GH dislocations are often accompanied by fractures of the greater tuberosity of the humerus: see p. 80.

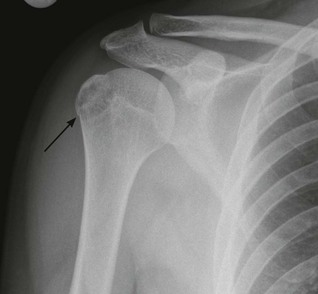

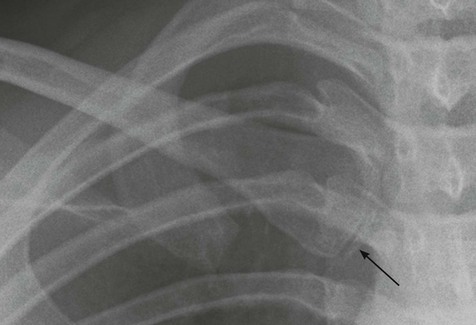

Anterior dislocation of the glenohumeral (GH) joint with accompanying fractures

A fracture of the greater tuberosity of the humerus frequently accompanies a dislocation.

Uncommon but important injuries

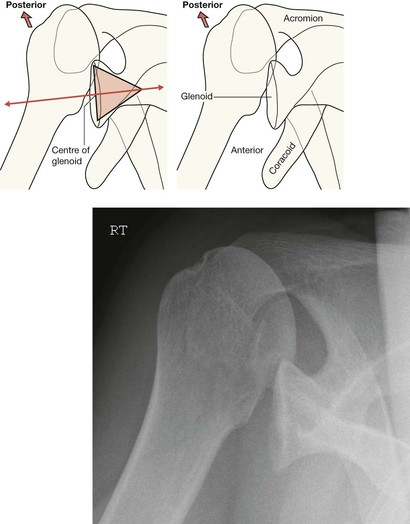

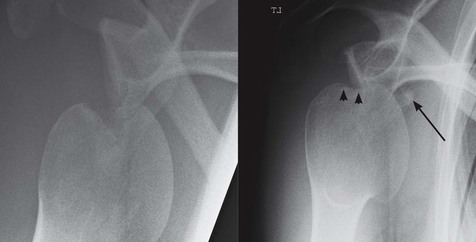

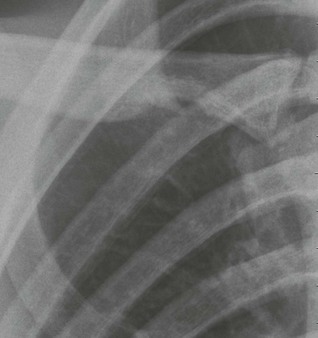

Posterior dislocation at the glenohumeral (GH) joint

The naming of this injury is arguably inaccurate. It is very rarely a complete dislocation. Despite the notable posterior displacement it is, invariably, a major subluxation.

On many occasions there will be an accompanying fracture of the anterior aspect of the humeral head.

Uncommon. Fewer than 5% of shoulder dislocations. As many as 50% are overlooked even when initial radiographs show the abnormality7.

Often caused by violent muscle contraction; either during a convulsion or from an electric shock. Sometimes, both shoulders will dislocate simultaneously8.

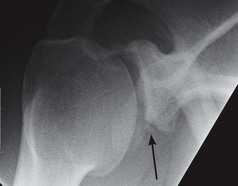

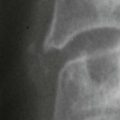

Fractures of the body or neck of the scapula

Usually result from a high impact event. Serious soft tissue or neurovascular injuries are recognised associations8.

You will only see what you look for…these fractures are easy to overlook. Always check the AP and the second view very carefully.

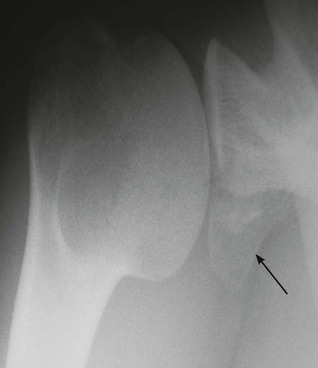

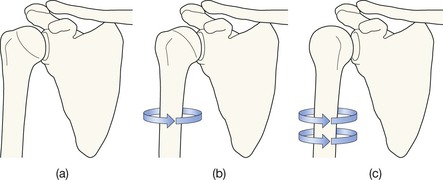

Inferior dislocation of the humeral head (luxatio erecta)

Very rare and accounts for less than 0.5% of all shoulder dislocations. The clinical finding is classical—a Statue of Liberty appearance with the arm elevated and the forearm fixed and resting on the head5,12. The AP radiograph shows the head of the humerus nestling immediately inferior to the glenoid with the humerus pointing upwards. Usual cause: forceful hyperabduction of an abducted limb.