CHAPTER FOUR SHOULDER

AXIOMS IN ASSESSING THE SHOULDER

INTRODUCTION

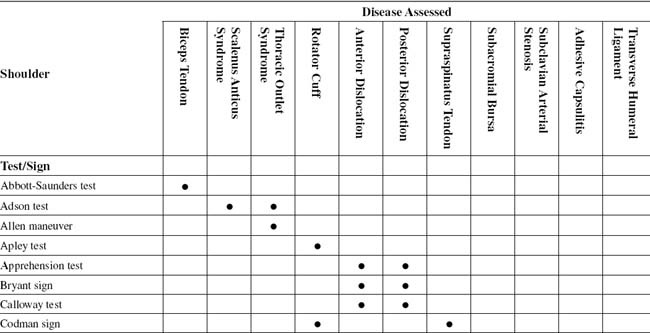

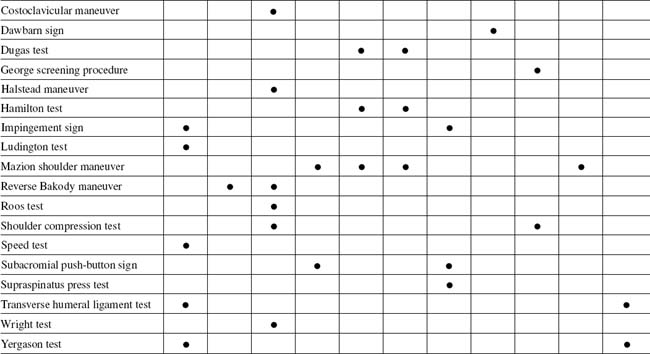

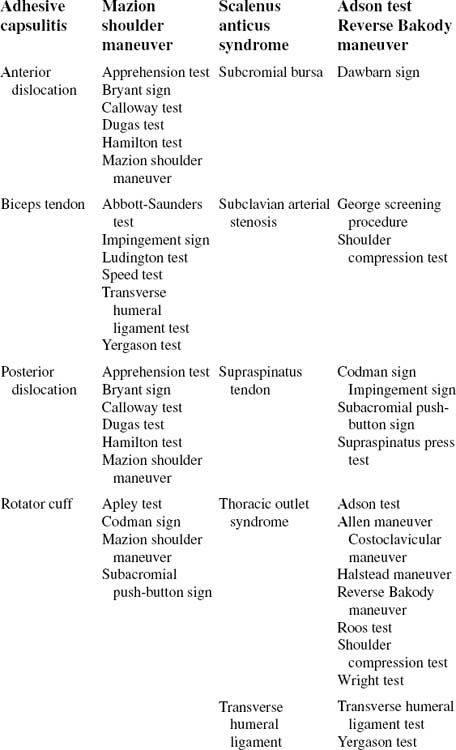

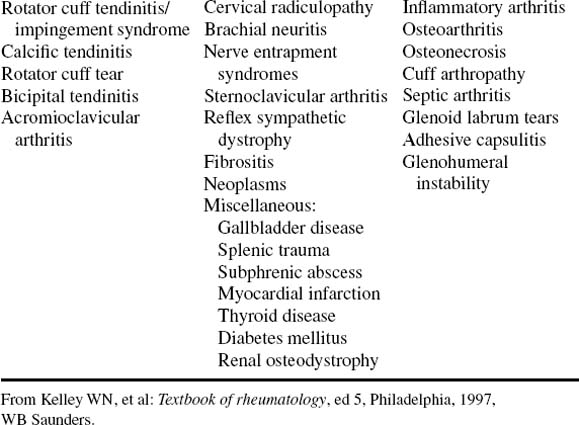

Referred pain to the shoulder can occur with cervical disorders, Pancoast tumor of the lung, a subphrenic pathologic condition, entrapment neuropathies, myofascial pain syndromes, and brachial neuritis (Table 4-3).

| Periarticular Disorders | Regional Disorders | Glenohumeral Disorders |

|---|---|---|

From Kelley WN, et al: Textbook of rheumatology, ed 5, Philadelphia, 1997, WB Saunders.

Identification of the primary cause of shoulder pain is not always easy. Referred pain to the shoulder girdle region occurs from multiple sources other than the neck. With diaphragmatic irritation, pain is referred along the phrenic nerve to the supraclavicular region, the trapezius, and the superomedial angle of the scapula. Gastric and pancreatic diseases may refer pain to the interscapular region. The rare superior sulcus lung tumor, or Pancoast tumor, occasionally coincident with Horner syndrome, may have shoulder pain as its initial symptom.

The mobility of this part of the body results from the configuration of the bony parts and the mechanically advantageous attachment of the multiple muscles. The shallow socket and ball head favor frictionless spinning, and the main joint has four accessory articulating zones that complement and enhance the action of the shoulder.

ESSENTIAL MOTION ASSESSMENT

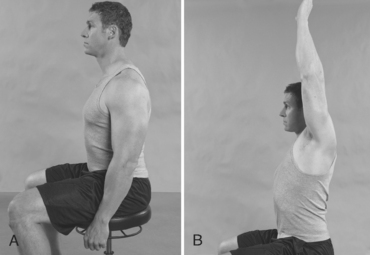

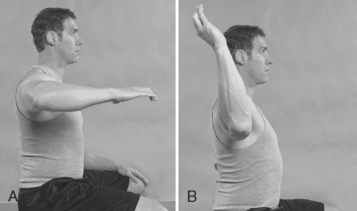

Shoulder motion is interpreted through excursion of the arm from the body and is recorded according to the anatomic planes (Fig. 4-1).

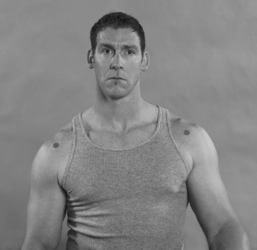

ESSENTIAL MUSCLE FUNCTION ASSESSMENT

The teres major muscle arises from the lower third of the lateral border of the scapula and travels around the anterior aspect of the humerus and in front of the long head of the triceps to insert onto the crest of the lesser tubercle. The teres minor and deltoid receive their innervation by the axillary nerve, whereas the teres major is supplied by the lower subscapular nerve (Figs. 4-8 to 4-13).

ABBOTT-SAUNDERS TEST

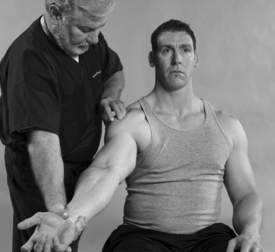

PROCEDURE

ADSON TEST (ALSO KNOWN AS SCALENE MANEUVER AND SCALENUS ANTICUS TEST)

PROCEDURE

ALLEN MANEUVER

Assessment for Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 4-8 THORACIC OUTLET SYNDROME CLASSIFICATIONS

Thoracic outlet syndrome (TOS) is categorized in three types:

PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

BRYANT SIGN

Assessment for Dislocation of the Glenohumeral Articulation

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 4-10 AXILLARY PSEUDOANEURYSM

PROCEDURE

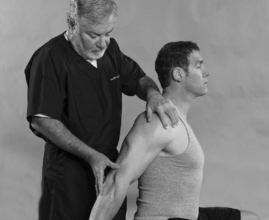

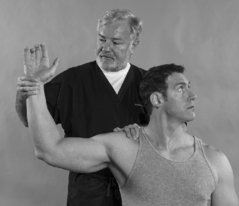

The examiner views the characteristic lowering of the axillary fold (anterior and posterior pillars of the armpit) that is seen after trauma when dislocation of the glenohumeral articulation ensues (Fig. 4-21).

CODMAN SIGN (ALSO KNOWN AS DROP ARM TEST)

PROCEDURE

COSTOCLAVICULAR MANEUVER

Assessment for Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 4-13 SYMPTOMS OF SUBCLAVIAN VENOUS OBSTRUCTION

PROCEDURE

DUGAS TEST

PROCEDURE

GEORGE SCREENING PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

HALSTEAD MANEUVER

PROCEDURE

HAMILTON TEST

PROCEDURE

IMPINGEMENT SIGN

Assessment for Overuse Injury to the Supraspinatus or Biceps Tendons

Comment

The terminology for impingement lesions had led to confusion. Many names and causes for this condition have been cited, including bursitis, tendinitis, acute trauma, overuse, instability, aging, tendon degeneration, vascular deficiencies, and mechanical impingement (Table 4-4). The rotator cuff is the only tendon situated between two bones.

TABLE 4-4 CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS OF THE MOST COMMON SHOULDER CONDITIONS

| Disorder | Age Group Affected | Key Diagnostic Features |

|---|---|---|

| Rotator cuff impingement | Middle-aged | Painful arc within full ROM |

| Rotator cuff tear | Middle-aged and older adults | Selective weakness of supraspinatus/infraspinatus |

| Frozen shoulder | Middle-aged | Restriction of passive ROM, external rotation |

| Calcific tendonitis | Middle-aged | Severe pain; full passive ROM; calcific deposit on radiograph |

| Acromioclavicular osteoarthosis | Middle-aged and older adults | Pain over joint; radiographic changes |

| Glenohumeral osteoarthosis | Middle-aged and older adults | Loss of passive ROM; radiographic changes |

| Shoulder instability | Age <40 years | Recurrent dislocation or subluxation symptoms; clinical signs of instability |

ROM, Range of motion.

Adapted from Frost A, Michael Robinson C: The painful shoulder, Surgery (Oxford) 24(11):363-367, 2006.

PROCEDURE

REVERSE BAKODY MANEUVER

Assessment for Cervical Foraminal Compression and Interscalene Compression

PROCEDURE

ROOS TEST

PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

SUBACROMIAL PUSH-BUTTON SIGN (ALSO KNOWN AS MAZION CUFF MANEUVER)

Assessment for Rotator Cuff Tear of the Supraspinatus Tendon

Comment

Ruptures of the rotator cuff result from continued deterioration and degeneration (Table 4-5). The tear may be partial or complete.

TABLE 4-5 GOUTALLIER GRADING SYSTEM OF FATTY DEGENERATION OF MUSCLE

| Stage | Findings (MRI/CT) |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Normal muscle; no fatty streaking |

| Stage 1 | Occasional fatty streaking |

| Stage 2: fat < 50% of cross | Sectional area (fat < muscle) |

| Stage 3: fat = 50% of cross | Sectional area (fat = muscle) |

| Stage 4: fat > 50% of cross | Sectional area (fat > muscle) |

CT, Computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

PROCEDURE

SUPRASPINATUS PRESS TEST

Assessment for Tear of the Supraspinatus Tendon or Muscle

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 4-28 SUPRASPINATUS SYNDROME

Variations of degeneration that lead to supraspinatus syndrome include the following:

PROCEDURE

PROCEDURE

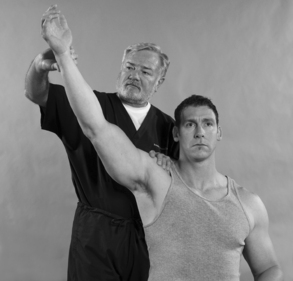

WRIGHT TEST (ALSO KNOWN AS HYPERABDUCTION MANEUVER)

PROCEDURE

YERGASON TEST

Assessment for Tenosynovitis or Involvement of the Transverse Humeral Ligament

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 4-31 HAWKIN IMPINGEMENT TEST

For the Hawkin impingement test:

ORTHOPEDIC GAMUT 4-32 SUPRASPINATUS TEST: EMPTY CAN TEST