Chapter 98 Should First-Time Shoulder Dislocators Be Stabilized Surgically?

DEFINING THE PROBLEM

The shoulder is a versatile complex of joints with a large functional range of motion. However, stability is sacrificed for this freedom of movement. The glenohumeral joint is a loosely opposed “ball-and-socket” type joint, and as such is the most commonly dislocated large joint in the body. The lifetime incidence of anterior shoulder dislocation has been reported to be 1% to 2% in the general population.1,2 Recurrent instability after primary dislocation is a common problem.

The clinical course of patients after nonsurgical treatment has been investigated extensively. Of particular interest is the relatively high rate of recurrent instability in young patients. Estimates of the recurrence rate in this group have been reported to be anywhere between 17% and 96%.2–10

The anatomic abnormality associated with the majority of traumatic shoulder dislocations is the Bankart lesion—an avulsion of the anterior glenoid labrum and shoulder joint capsule at the insertion of the inferior glenohumeral ligament. The anterior capsulolabral complex is thought to be the major stabilizer of the shoulder to anterior subluxation. The frequency of recurrence, therefore, is postulated to be related to failure of this complex to heal in an anatomic position. Proponents of acute arthroscopic Bankart repair have emphasized that it is the ability to directly oppose and secure the lesion to its anatomic position at surgery that imparts immediate stability versus nonoperative methods. Early series of arthroscopic treatment of shoulder instability have shown it to be an effective modality in decreasing recurrence.11,12

Despite evidence in favor of arthroscopic stabilization, uncertainty still exists among the orthopedic community as to optimal timing of surgical intervention.13,14 The cost, risk, and anxiety associated with surgery have caused some surgeons to adopt a strategy of “watchful neglect,” allowing patients to demonstrate recurrent episodes of instability or dislocation before proceeding with an operative solution. Furthermore, although early surgery has the potential to result in a number of patients avoiding redislocation in the short term, the long-term functional benefits over a conservative approach are less well known.

There were 43 potentially relevant study titles. More studies were identified secondarily on the basis of bibliographical reviews and hand searches of proceedings. Application of the study eligibility criteria eliminated 11 of the original titles, with 32 articles remaining for review: 13 describe primarily nonsurgical management, 9 describe arthroscopic interventions, 4 are observational studies that include the results for both surgically and nonsurgically treated patients, and 6 are randomized trials.

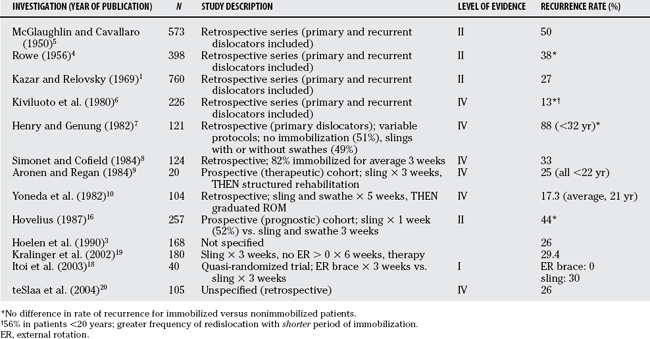

NONSURGICAL STUDIES

In those reports predating 1990, retrospective (Level II, III, and IV) studies predominate.4–6 These series are subject to the limitations of bias and confounding inherent in any investigation that relies on retrospectively collected data. Furthermore, most of these series include both primary and recurrent dislocators in the study sample. Perhaps the largest early series is that of Rowe and colleagues,4 which reports on 488 patients with shoulder dislocations seen at Massachusetts General Hospital during the 20-year period from 1934 to 1954. Of the entire group, 398 (82%) were patients with primary dislocations with the remainder being recurrent. No information is provided as to immobilization or rehabilitative protocols prescribed for these patients. Although the inclusion of patients with recurrent instability makes it difficult to draw specific inferences on those patients with primary instability, Rowe was the first to document a relatively high recurrence rate (38%) after primary dislocation in a large series and to make conjectures about possible prognostic factors for recurrence including young age at initial dislocation and traumatic cause. Age was identified as the strongest single prognostic factor, with 83% of those patients younger than 20 years going on to further instability episodes.

In more recent investigations, there has been conflicting information as to the rate of recurrent instability and the optimum nonsurgical management. Henry and Genung7 reported on a group of 121 first-time dislocators that was also reviewed retrospectively (Level II). A rate of recurrence of 85% to 90% was noted in these patients within 18 months of the injury; this was significantly greater than the previous reports of Rowe and others.4 All patients in that study were younger than 32. Half of the group was immobilized in a sling for a variable period. Although randomization was not performed, equivalent rates of recurrent instability in immobilized and nonimmobilized patients led the authors to conclude that immobilization was of little benefit in reducing recurrence. Another Level III retrospective series of 124 patients by Simonet and Cofield8 reports a lower overall rate of recurrence (33%), but again stresses the importance of age as a risk factor with more than 50% of those patients younger than 40 years experiencing further instability.

Controversy as to the optimal rehabilitation program after first-time dislocation was introduced by both Aronen and Regan,9 as well as Yoneda and coworkers,10 who reported seemingly lower recurrence rates of 25% and 17.3%, respectively, with aggressive physical therapy. The former of these investigations was prospectively conducted on a small cohort of young male military cadets (n = 20)—a recognized “high-demand” population (Level IV). The authors used a rigorous rehabilitation protocol. Despite the fact that this protocol was described in detail, subsequent studies utilizing it on a similar population have failed to replicate the results.11

A prospective, multicenter cohort study was initiated in 1978 in a Swedish population (Level II). The results of this cohort have been published at 2-, 5-, and 10-year follow-up.15–17 The group of 247 primary dislocations in patients between the ages of 12 and 40 years were quasi-randomized (on the basis of even or odd date of injury) to receive one of three methods of conservative treatment: sling and swathe for 3 weeks, sling for 1 week followed by restricted range of motion, or a “mixed” treatment for patients believed to be unfit for either of the first two arms. No significant differences were found in the rate of recurrent dislocations at 10 years after injury among the three groups. Overall, approximately 50% of the patients had experienced symptoms of instability at 10-year follow-up. Young age was again put forth as the single strongest predictor for recurrence. The presence of an associated fracture of the greater tuberosity was identified as protective. No association between recurrent instability and sex, handedness, or side of dislocation was identified. This Level I prognostic study represents the highest current level of evidence available regarding the natural history of anterior shoulder dislocations with long-term, prospectively collected data. This study has an impressively low loss to follow-up (3%) over the 10-year course.

A recently published study has suggested that immobilizing acutely dislocated shoulders in a position of relative external rotation reduced subsequent dislocation rates.18 In a quasi-randomized prospective trial (Level II), Itoi and coauthors18 demonstrate a 0% recurrence rate in 20 patients immobilized in external rotation versus a 30% recurrence rate in 20 patients immobilized in a sling at a mean follow-up of 15.5 months. Several randomized clinical trials are ongoing in Canada, the United States, and Australia to test this concept in a young at-risk population. The characteristics of the nonoperative studies are outlined in Table 98-1.

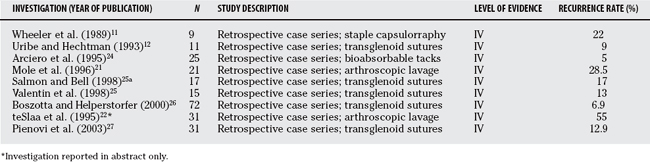

Arthroscopic Studies

The appearance in the literature of studies that address arthroscopic stabilization as a primary treatment modality for acute shoulder dislocations has been a relatively recent phenomenon. Before the advent of arthroscopy, operative management was usually considered only after a patient had demonstrated symptomatic recurrent instability. Arthroscopic stabilization has become increasingly popular for the treatment of shoulder instability because it offers potential advantages over formal open techniques including improved cosmesis, superior intra-articular visualization, and minimized disruption of the anterior soft tissues. Specifically, in the setting of a primary dislocation, the decreased morbidity offered by the arthroscopic approach—combined with the acuity of the Bankart lesion and its amenability to repair in this state—have made it an especially attractive option to surgeons who recognize the potential for recurrent instability with traditional nonoperative treatments.

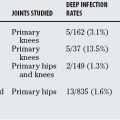

The risk for recurrence after arthroscopic stabilization has been reported in several series, which are summarized in Table 98-2. Unfortunately, few reports distinguish between acute and recurrent dislocations when presenting the results of these primarily retrospective series. In addition, a variety of different arthroscopic stabilization techniques is used in these studies, each with its own associated surgical “learning curve” and spectrum of complications. Identifying surgical complications and deriving estimates of patient satisfaction (beyond recurrence) from historical chart review is problematic. Keeping this in mind, it would still seem that the incidence of recurrent instability is tangibly reduced with early arthroscopic repair. Inferences beyond that are difficult.

Early diagnostic arthroscopy without stabilization has also been suggested to be useful in reducing the rate of recurrent shoulder instability. In two prospective studies, patients underwent arthroscopic lavage only.21,22 The rationale for this procedure was both diagnostic and therapeutic. In removing intra-articular clot and debris, investigators suggest acute arthroscopic lavage allows the Bankart lesion to heal in an anatomically reduced position. Mole and colleagues21 performed arthroscopic lavage on 30 patients within 4 days of an initial dislocation. Of the 21 (70%) patients available for follow-up at 24 months, 6 (28.5%) developed recurrent instability. teSlaa and coworkers20 performed arthroscopy on 31 patients within 10 days of a first-time dislocation. At 5-year follow-up, 12 patients (38.7%) had sustained a recurrent dislocation, and a total of 17 patients (55%) had described at least 1 episode of symptomatic subluxation during the study period. From the results of this study, and that of Mole and colleagues,21 the evidence of benefit with isolated arthroscopic lavage would seem to be weak.

Surgical complications were infrequent in the arthroscopic series reviewed. Traditionally, the rate of reported complications in large series of arthroscopic stabilizations for recurrent instability has also been low.23 Complications were generally of low morbidity, ranging from stiffness (mildly decreased external rotation >30 degrees) in the involved shoulder to a surgical infection (n = 1) requiring repeat debridement and intravenous antibiotics. The overall complication rate for all the arthroscopic stabilizations reviewed was less than 1%. This is consistent with previous reports of complications after similar procedures for recurrent glenohumeral instability.23

Further characteristics of the arthroscopic series included in this review are presented in Table 98-2. Over time, recurrence rates have generally decreased without a corresponding increase in the incidence of complications. This is due in part to the increasing familiarity of surgeons with arthroscopic procedures, as well as refinements of the technique and equipment. Methods utilizing suture anchors are now the standard because the anterior labrum can be most securely approximated in an anatomic fashion with these devices.

COMPARATIVE STUDIES

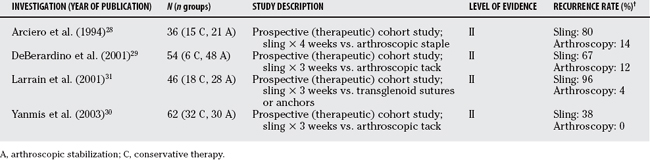

Nonrandomized (Observational) Studies

In an effort to improve the quality of evidence in favor of acute arthroscopic stabilization, prospective trials were initiated at several U.S. military academies.28,29 Investigators from these institutions had previously published series of both conservatively and arthroscopically treated first-time dislocations and were, in their own words, biased to the merits of the arthroscopic approach. In separate trials, Wheeler11 and Deberardino29 prospectively evaluated cohorts of patients, all male military cadets, who were allowed to choose between conservative or arthroscopic treatment. Similarly, a recent Turkish study reports on 2 groups of arthroscopically stabilized and conservatively treated attendees at a military academy.30 Again, these patients were allowed to choose their own treatment. All of these trials demonstrate a strong benefit with arthroscopic stabilization in limiting subsequent symptomatic instability. Inferences as to the true benefit of arthroscopy, however, are weakened by the potential for selection bias in the absence of randomization. A fourth prospective study, this one conducted on South American rugby players, reiterates the finding of significantly lower incidence of symptomatic instability with surgical intervention.31 All the aforementioned investigations, although observational, have significance in the literature because they introduced the concept of acute surgical stabilization of the dislocated shoulder as a viable treatment alternative, thereby paving the way for the randomized trials that were to come. The characteristics of comparative, non-randomized investigations are discussed in Table 98-3.

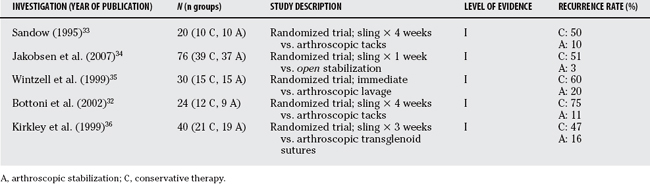

Randomized Studies

Criticism fell on the aforementioned military trials both for failure to randomize and for a lack of generalizability. The military cadet population was seen as an extremely high-demand group of patients whose significant risk for recurrent instability may not reflect that seen in the general civilian population. A randomized trial was subsequently conducted in a military population. Bottoni and colleagues32 reported the results of 24 cadets quasi-randomly allocated (on the basis of social insurance number) to receive arthroscopic stabilization (n = 14) versus nonoperative treatment (n = 10). Of those patients available for follow-up at an average of 36 months from the time of dislocation, recurrent instability was seen in 75% of the nonoperative group as compared with only 11% (1/9) of the arthroscopic group. Unequal group sizes may reflect the strictly nonrandom nature of treatment allocation.

Two other randomized investigations comparing surgical interventions with conservative treatment for primary shoulder dislocators have been conducted. Sandow33 has provisionally reported on 20 patients, all of whom were younger than 26 years, randomized to receive arthroscopic stabilization with a bioabsorbable tack versus sling immobilization for 4 weeks. Recurrence was significantly lower in the surgical group with only 1 of 10 patients demonstrating symptomatic instability (10%) versus 5 of 10 (50%) in the sling group. In the only investigation that included patients who underwent acute open stabilization, Jakobsen and coworkers34 also found a significantly lower rate of redislocation with patients randomized to surgery (1/37; 2.7%) versus those immobilized in a sling for 1 week followed by therapy (20/39; 51%). This randomized trial includes prospectively collected data out to 10 years after dislocation.

On the suggestion that arthroscopic lavage may reduce recurrence, Wintzell and researchers35 conducted a randomized trial to compare this treatment with sling immobilization. Arthroscopic lavage was performed within 10 days of dislocation in 15 patients. Another 15 patients (with no specific randomization scheme described) were given an optional sling for 1 week and encouraged to move the shoulder freely. At the 2-year follow-up examination, 3 (20%) of the patients in the lavage group had redislocated versus 9 (60%) in the nonoperative group.

Kirkley and coworkers36 performed a randomized clinical trial on civilian patients. Forty patients younger than 30 years were allocated, on the basis of a permuted block, computer-generated, randomization scheme, to receive sling immobilization (n = 21) or undergo acute arthroscopic stabilization (n = 19) after first-time dislocation. The rate of recurrence at the 2-year follow-up was significantly lower in the arthroscopic group (47% vs. 15.9%). This study had few, if any, deficiencies with its design or analysis and remains the highest level of evidence in support of early arthroscopic stabilization to reduce recurrence. Secondary outcomes included validated general and disease-specific quality-of-life measurement tools. A preliminary analysis of patient-based outcomes at 2-year follow-up suggested a statistically higher level of function in those patients who underwent early arthroscopy. The clinical significance of the 15% difference in disease-specific outcome at final follow-up favoring the patients treated arthroscopically is unclear. This is due in part to the relative “newness” of the outcome measure used and the fact that function was considered a secondary outcome (therefore, the study may not have been adequately powered to show a clinically significant difference in function). Nonetheless, the results have important implications. If acute arthroscopy serves only to reduce early recurrence rates, with no significant long-term functional benefit, then an approach that optimizes conservative treatment may provide the greatest overall benefit to patients, whereas simultaneously limiting potential complications. The characteristics of all the comparative and/or randomized investigations are summarized in Table 98-4.

CONCLUSIONS

Prognosis after First-Time Dislocation

The true rate of recurrent instability after primary anterior glenohumeral dislocation remains imprecise, with series reporting estimates that range from 17% to 90%. With few exceptions, most reports would suggest the rate of recurrent dislocation or symptomatic subluxation, or both, in young patients approaches 50%. Greater rates have been demonstrated in series with larger proportions of younger patients, males, and active military recruits. Even in the absence of recurrent instability, prospectively collected, disease-specific, health-related quality-of-life data suggest patients demonstrate prolonged functional deficits after a primary dislocation.37 Age has been repeatedly demonstrated as the most significant prognostic factor in predicting recurrence. Recently, teSlaa and coworkers20 have attempted to quantify this risk based on the odds ratio of recurrence with various age distributions. They suggest the risk for recurrence decreases by a factor of 0.09 (9%) with each additional year of patient age at the time of initial dislocation.

The presence of associated fractures was of variable prognostic significance in the development of recurrent instability. Fractures of the greater tuberosity seem to impart a protective effect that is independent of age and the degree of shoulder stiffness (associated with fracture immobilization).19 Fractures of the humeral head (Hill–Sachs lesion) and anterior glenoid rim (the bony Bankart lesion) are suggested to increase the risk for recurrence; however, the difficulty of diagnosing and quantifying these lesions, particularly in retrospective studies, has made a definitive association elusive.

Role of Nonoperative Treatment

The optimal conservative management strategy after first-time shoulder dislocation remains unknown. Rehabilitation strategies have generally not been effective in reducing the rate of recurrent instability. Aronen and Reagan’s9 and Yoneda and coworkers’10 reports, which describe recurrence rates on the order of 20%, are seemingly anomalous. Similarly, traditional immobilization devices such as a sling and/or sling and swathe have not altered the natural history after first-time dislocation. A relatively large prospective cohort with long-term follow-up (Level I prognostic evidence) has demonstrated equivalent recurrence rates with sling immobilization versus early range of motion and therapy.17 Preliminary results from a small randomized trial have suggested merit in a novel immobilization strategy positioning the affected limb in external rotation.18

Role of Arthroscopy

A dramatic benefit was demonstrated with early open or arthroscopic stabilization in reducing recurrence rate after acute dislocations.34,36 Several questions remain to be answered, however. The presence or absence of recurrent instability cannot be considered an appropriate surrogate for functional outcome. Patients may not experience a subsequent dislocation solely because of discontinuation of the activities that put them at risk. This point underpins the importance of assessing patient function as a primary outcome when conducting future investigations. The lack of a universally accepted, instability-specific outcome tool has made this difficult in the past. The introduction of the Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI), a tool with proven reliability, responsiveness, and validity, may make the assessment of patient-based functional outcomes after dislocation more consistent in the future.38

Debate over the role of early arthroscopy continues in the orthopedic community. Despite the relatively high level of evidence in support of this approach, some surgeons remain reluctant to expose patients to the risk, cost, and anxiety of surgery after a single dislocation episode. Kirkley and coworkers’38 trial de-monstrates that, although arthroscopy definitively reduces recurrence in the short term, functional benefits may not be as substantial. If we assume that function is not significantly improved with arthroscopy, then methods to reduce recurrence with nonoperative treatment may be the best approach. Itoi and coauthors’18 trial suggests immobilization of the affected shoulder in a position of external rotation may be one such method.

As with any systematic review, the strength of inference is only as good as the quality of the primary studies and the scientific rigor with which the review was conducted. Meta-analyses that pool data from nonrandomized studies are subject to all of the limitations of the primary studies. Thus, combining the results of nonrandomized studies may result in a biased pooled estimate of effect that reflects the biases inherent to the observational studies.39 The estimates of treatment effect described in the current review were generated from pooling only randomized investigations and, therefore, may be more reflective of the true benefits imparted by early arthroscopic intervention over traditional nonoperative methods.

The Cochrane group has published a review of surgical versus nonsurgical treatments for acute anterior shoulder dislocations (January 2004). The current review and the published Cochrane review were conducted independently and are similar in their findings with respect to the benefit of acute arthroscopic stabilization. Whereas the scope of the current review is broad, including all literature on the orthopedic management of primary shoulder dislocations, the Cochrane review has included only five randomized investigations that directly compare surgical versus nonsurgical interventions.40

Implications for Research

Future trials comparing arthroscopic and conservative treatments for first-time shoulder dislocation must include validated functional outcome measures as primary end points and be planned with a priori sample sizes sufficient to demonstrate clinically important differences in these outcomes. Such trials would optimally be conducted on groups of patients from the general population (vs. military or other homogenous populations) to improve the generalizability of the inferences that can be made. Table 98-5 provides a summary of recommendations.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE | GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|---|

| I: Good evidence | NA | |

| I: Good evidence | A | |

| I: Good evidence | A | |

| I: Good Evidence | A | |

| II: Fair evidence | B | |

| II: Fair evidence | B | |

| II: Fair evidence | B |

NA, not applicable

1 Kazar B, Relovsky E. Prognosis of primary dislocations of the shoulder. Acta Orthop Scand. 1969;40:216-224.

2 Hovelius L. Incidence of shoulder dislocations in Sweden. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 166; 1982; 127-131.

3 Hoelen MA, Burgers AMJ, Rozing PM. Prognosis of primary anterior shoulder dislocation in young adults. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1990;110:51.

4 Rowe CR. Prognosis in dislocations of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1956;38-A:957-977.

5 McGlaughlin HL, Cavallaro WU. Primary anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Am J Surg. 1950;80:615.

6 Kiviluoto O, Pasila M, Sundholm JA. Immobilization after primary dislocation of the shoulder. Acta Orthop Scand. 1980;51:915.

7 Henry JH, Genung JA. Natural history of glenohumeral dislocation revisited. Am J Sports Med. 1982;10:135-137.

8 Simonet WT, Cofield RH. Prognosis in anterior shoulder dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12:19-21.

9 Aronen JG, Regan K. Decreasing the incidence of recurrence of first time anterior shoulder dislocations with rehabilitation. Am J Sports Med. 1984;12:283-291.

10 Yoneda B, Webb RP, MacIntosh DL. Conservative treatment of shoulder dislocations in young males. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64-B:254.

11 Wheeler JH, Ryan JB, Arciero RA, Molinari RN. Arthroscopic versus nonoperative treatment of acute shoulder dislocations in young athletes. Arthroscopy. 1989;5:213-217.

12 Uribe JW, Hechtman KS. Arthroscopically assisted repair of acute bankart lesion. Orthopedics. 1993;16:1019-1023.

13 Arciero RA. Acute arthroscopic bankart repair? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8:127-128.

14 Eriksson E. Should first-time traumatic shoulder dislocations undergo an acute stabilization procedure? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2003;11:61-62.

15 Hovelius L, Eriksson K, Fredin H, et al. Recurrences after initial dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65-A:343-349.

16 Hovelius L. Anterior dislocation of the shoulder in teenagers and young adults: Five year prognosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69-A:393-399.

17 Hovelius L, Augustini BG, Fredin H, et al. Primary anterior dislocation of the shoulder in young patients: A ten year prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78-A:1677-1684.

18 Itoi E, Hatakeyama Y, Kido T, et al. A new method of immobilization after traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder: A preliminary study. J Shouler Elbow Surg. 2003;12:413-416.

19 Kralinger FS, Golser K, Wischatta R, et al. Predicting recurrence after primary shoulder dislocation. Am J Sport Med. 2002;30:116-120.

20 teSlaa RL, Wijffels PJM, Brand R, Marti K. The prognosis following acute primary glenohumeral dislocation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86-B:58-64.

21 Mole D, Coudane H, Rio B, et al. The role of arthroscopy during the first episode of anteromedial luxation of the shoulder: Lesion assessment and recurrence factors. J Traumatol Sport. 1996;13:20-24.

22 teSlaa RL, Ritt M, Jansen BRH: A prospective arthroscopic study of acute initial anterior shoulder dislocation in the young [abstract]. Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Surgery of the Shoulder. Helsinki, June 1995.

23 Green MR, Christensen MD. Arthroscopic versus open Bankart procedures: A comparison of early morbidity and complications. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:371-374.

24 Arciero RA, Taylor DC, Snyder RJ, et al. Arthroscopic bioabsorbable tack stabilization of initial anterior shoulder dislocations: A preliminary report. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:410-417.

25 Valentin A, Winge S, Engstrom B. Early arthroscopic treatment of primary anterior shoulder dislocation. A follow-up study. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1998;8:405-410.

25a Salmon JM, Bell SN. Arthroscopic stabilization of the shoulder for acute primary dislocations using a transglenoid suture technique. Arthroscopy. 1998;14(2):143-147.

26 Boszotta H, Helperstorfer W. Arthroscopic transglenoid suture repair for initial anterior shoulder dislocation. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:462-470.

27 Pienovi A, Quevedo L, Orive AG: Arthroscopic treatment of the first shoulder dislocation [abstract]. AAOS Annual Meeting. New Orleans, 2003.

28 Arciero RA, Wheeler JH, Ryan JB, McBride JT. Arthroscopic Bankart repair versus nonoperative treatment for acute, initial anterior shoulder dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22:589-594.

29 DeBerardino TM, Arciero RA, Taylor DC, Uhorchak JM. Prospective evaluation of arthroscopic stabilization of acute, initial anterior shoulder dislocations in young athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:586-592.

30 Yanmis I, Tunay S, Komurcu M, et al. The outcomes of acute arthroscopic repair and conservative treatment following first traumatic dislocation of the shoulder joint in young patients. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2003;32:824-827.

31 Larrain MV, Botto GJ, Montenegro HJ, et al. Arthroscopic repair of acute traumatic anterior shoulder dislocations in young athletes. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:373-377.

32 Bottoni CR, Wilckens JH, DeBerardino TM, et al. A prospective, randomized evaluation of arthroscopic stabilization versus nonoperative treatment in patients with acute, traumatic, first-time shoulder dislocations. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:576-580.

33 Sandow MJ. Arthroscopic repair for primary shoulder dislocation: A randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77-B(supp I):67.

34 Jakobsen BW, Johannsen HV, Suder P, Søjbjerg JO. Primary repair versus conservative treatment of first-time traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder: A randomized study with 10-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:118-123.

35 Wintzell G, Haglund-Akerlind Y, Nowak J, et al. Arthroscopic lavage with nonoperative treatment for traumatic primary anterior shoulder dislocation: A two-year follow-up of a prospective randomized study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:399-402.

36 Kirkley A, Griffen S, Richards C, et al. Prospective randomized clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of immediate arthroscopic stabilization versus immobilization and rehabilitation in first traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:507-514.

37 Kirkley A, Werstine R, Ratjek A, Griffen S. Prospective randomized clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of immediate arthroscopic stabilization versus immobilization and rehabilitation in first traumatic anterior dislocations of the shoulder: Long-term evaluation. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:55-63.

38 Kirkley A, Griffen S, McLintock H, Ng L. The development and evaluation of a disease specific quality of life measurement tool for shoulder instability: The Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI). Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:764-772.

39 Concata J, Shah N, Horwitz RI. Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research design. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1887-1892.

40 Handoll HHG, Almaiyah MA, Rangan A. Surgical versus non-surgical treatment for acute anterior shoulder dislocation (Review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev.; 1; 2004; CD004325.