Chapter 4 Shortness of breath

Introduction

Shortness of breath is the chief complaint in approximately 8% of 999 calls to the ambulance service, and is the third most common type of emergency call. It can also be an important symptom in patients with a wide range of conditions. Reference should therefore be made to other relevant chapters – particularly that discussing chest pain (Chapter 3). The conditions covered in this chapter include asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, acute pulmonary oedema and chest infections. The objectives are listed in Box 4.1.

Box 4.1 Chapter objectives

To describe the recognition of primary survey positive patients and treatment of immediately life threatening problems

To describe the recognition of primary survey positive patients and treatment of immediately life threatening problemsThe common causes of shortness of breath are asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pulmonary oedema but there are many other conditions that can pose diagnostic problems (Box 4.2).

Primary survey positive patients

Recognition

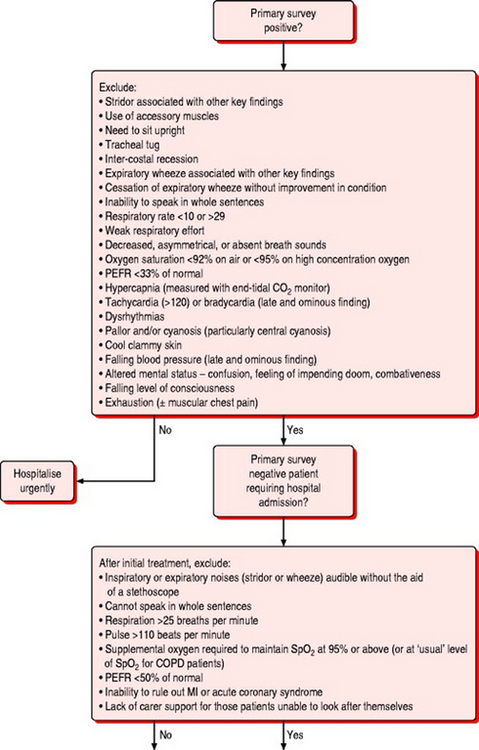

Patients with a life threatening respiratory emergency will present in either respiratory failure or respiratory distress. Patients with respiratory distress are still able to compensate for the effects of their illness, and urgent treatment may prevent their further deterioration. They present with signs and symptoms indicating increased work of breathing but findings suggesting systemic effects of hypoxia or hypercapnia will be limited or absent. Conversely, patients with respiratory failure may have limited evidence of increased work of breathing as they become too exhausted to compensate. The systemic effects of hypoxia and hypercapnia will be particularly evident in this group and immediate treatment will be required to prevent cardiac arrest. The key findings of primary survey positive patients with shortness of breath are presented in Box 4.3.

Box 4.3 Recognition of the primary survey positive patient with shortness of breath

Treatment

If it is not possible to obtain an airway, if the patient’s condition is deteriorating rapidly, or they show signs of significant respiratory failure (in particular failure to maintain SpO2 of 95% on high concentration oxygen) consider immediate transportation to a hospital with appropriate facilities. Important treatment points for primary survey positive patients are listed in Box 4.4.

Box 4.4 Treatment for primary survey positive patients

Treatment before transportation

Primary survey negative patients with need for hospital attendance

Primary survey negative patients with the findings listed in Box 4.5 who do not respond to pre-hospital treatment will require hospital admission.

Box 4.5 Diagnostic criteria for primary survey negative patients requiring hospital admission

Findings (not reversed by initial treatment) suggesting need for hospital admission:

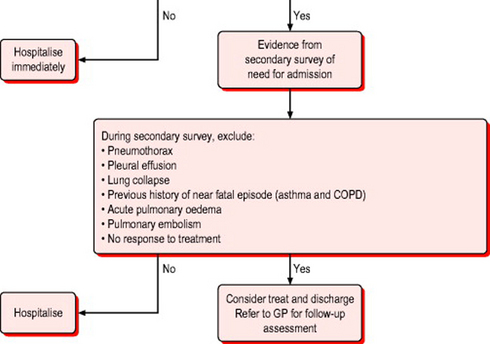

Secondary survey

The SOAPC system should be used to undertake a secondary survey (see Chapter 2). In primary survey positive patients, a secondary survey may not be completed in the pre-hospital phase of treatment as the focus must be on treatment of life threatening problems. For primary survey negative patients requiring hospital care the secondary survey may be undertaken during transportation. For the remaining patient population a secondary survey may be undertaken at the point of contact and will contribute to the decision to admit, treat and refer, or treat and leave.

Subjective assessment

Confirm that the chief complaint is shortness of breath. Remember that this may be a symptom of conditions affecting systems other than the chest (for example, hypovolaemia due to bleeding). Determine if this is a new problem or an exacerbation of a chronic condition. Ask what precipitated the problem and what, if anything, makes the patient feel more or less breathless. Ask about associated symptoms, such as chest pain, cough and sputum production, palpitations, fever and malaise, and leg pain or swelling. Has the patient been using inhalers or nebulisers more than normal? Have they recently sought other medical assistance?

Objective examination

Vital signs

The vital signs that should be recorded in a patient with shortness of breath are listed in Box 4.6.

Social context

In addition to the clinical assessment, it is important to consider the patient’s ability to care for themselves or whether suitable support mechanisms are available. If these are absent, can they be arranged? Can the patient perform the normal activities of daily living – feeding, washing and using the toilet – either with or without support? The time of day and day of the week may also influence the decision about whether to admit or refer the patient, as this may dictate how quickly a patient could be seen by their own GP or reviewed by the emergency care practitioner.

General examination

Look for signs of the ‘unwell’ patient (see Chapter 2). A detailed examination of the respiratory system is mandatory for patients with shortness of breath. Remember, however, that myocardial infarction, acute coronary syndromes and congestive cardiac failure can also result in respiratory distress, as may endocrine and neurological problems (for example Kussmaul’s and Cheyne–Stokes respiration in hyperglycaemia and raised intra-cranial pressure respectively). If a respiratory problem cannot be readily identified as the cause of the patient’s symptoms, undertake an examination of the other systems.

Elderly patients are likely to have multiple pathologies, so undertake a general systems examination

For details of the respiratory examination, refer to Boxes 4.3, 4.5, 4.6 and 4.7 and to Chapter 2. Note if the patient has excessive production of sputum. What colour is this? Yellow, green or brown sputum indicates a chest infection. White frothy sputum, which may also be tinged with pink, suggests pulmonary oedema.

Listen to the chest. Percuss the anterior and posterior chest wall bilaterally at the top, middle and bottom of the back. Is the percussion note normal, dull or hyper-resonant? Auscultate the chest at the same locations and in the axillae while the patient breathes in and out of an open mouth. Listen for the sounds of bronchial breathing, wheeze or crackles. Listen for vocal resonance and pleural rubs. Vocal resonance is assessed by asking the patient to whisper ‘one, two, three’ and listening with a stethoscope in the areas described for assessing TVF. Some resonance (although not the words themselves) should normally be detected and differences between areas should be noted as described above. Increased sound transmission, demonstrated by clear detection of words spoken by the patient and known as whispering pectoriloquy, is abnormal. Both TVF and vocal resonance are used to assess for the presence of consolidation (increased resonance) or pneumothorax or pleural effusion (decreased resonance).

In all patients with sudden onset of shortness of breath and in the absence of other findings strongly suggestive of a respiratory problem, undertake an examination of the cardiovascular system (see Chapters 2 and 3).

The pertinent features of the respiratory examination are summarised in Box 4.7.

Analysis (differential diagnosis)

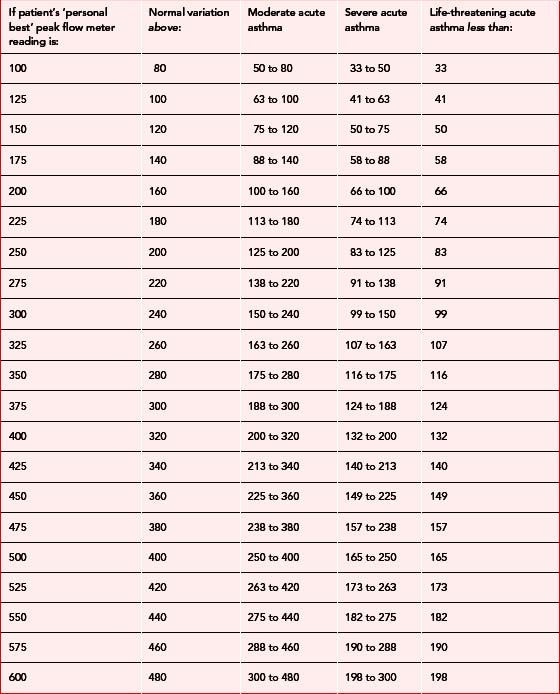

Diagnosis is often straightforward with a typical history and findings. For example the patient presenting with wheeze and tachypnoea may state that they have asthma. The skill is in determining the severity of the condition. Few patients die due to the misdiagnosis of asthma but significant numbers die because professionals or patients under-estimate the severity of an attack. Differential diagnosis can also be very difficult, classically in distinguishing between an exacerbation of COPD and cardiogenic pulmonary oedema. This may be made simpler by the use of b-naturetic peptide (BNP) estimations. This has recently been made available as a near-patient test and may become increasingly common in the out-of-hospital setting.

Asthma

The pointers in history and examination in patients with asthma that help to gauge the severity of an attack are summarised in Table 4.1. Patients with severe or life threatening asthma need calm reassurance (even if the healthcare provider is personally anxious), early treatment with beta-2 agonists, oxygen and immediate transfer to hospital. Patients with mild or moderate attacks who respond well to treatment may be suitable for home management with further inhaled beta-2 agonists, oral steroids and early review (Box 4.8 and Table 4.1).1

Box 4.8 Differential diagnosis of asthma

Subjective assessment

Decreasing wheeze in the absence of recovery is a serious finding suggesting grossly inadequate ventilation

Decreasing wheeze in the absence of recovery is a serious finding suggesting grossly inadequate ventilation History of previous hospital admission (particularly ICU)/need for ventilation is cause for significant concern, suggesting brittle asthma

History of previous hospital admission (particularly ICU)/need for ventilation is cause for significant concern, suggesting brittle asthmaCOPD

Oxygen treatment in these patients should be titrated against the SpO2 (controlled oxygen therapy – see the North-West Oxygen Group guidelines2). If the attack is not severe and the patient has adequate home support, then hospital admission may be avoided (Box 4.9).3

Acute cardiogenic pulmonary oedema

The onset is often sudden and severe. The patient is older and usually has a history of ischaemic heart disease although this may be the first indication of heart problems. Acute MI is often a precipitating factor. Severe shortness of breath, white frothy sputum, tachypnoea, tachycardia, pallor and sweating are common. Such patients need to be transported to hospital, sitting upright if possible. Immediate treatment consists of buccal nitrates (providing the blood pressure is not low), oxygen and intravenous opiates (Box 4.10).

Box 4.10 Differential diagnosis of acute pulmonary oedema (left ventricular failure/LVF)

Subjective assessment

Pneumonia

Pyrexia, malaise and purulent sputum suggest a diagnosis of pneumonia. The criteria for home treatment vary from country to country (Box 4.11).4

Box 4.11 Differential diagnosis of shortness of breath with pyrexia and malaise (pneumonia)

Subjective assessment

Predisposing factors, such as influenza, smoking, suppressed cough reflex (e.g. coma), pulmonary oedema, COPD, alcoholism, immunosuppression, long-term administration of broad spectrum antibiotics, general debility or immobility

Predisposing factors, such as influenza, smoking, suppressed cough reflex (e.g. coma), pulmonary oedema, COPD, alcoholism, immunosuppression, long-term administration of broad spectrum antibiotics, general debility or immobilityThere may be evidence of failure to cope with normal activities of daily living

Conditions for exclusion if hospital attendance is not considered appropriate

Box 4.5 lists the key findings that indicate the need for immediate hospital admission in primary survey negative patients. Table 4.2 describes additional findings determined from the secondary survey that will suggest the need for hospital admission. In asthma or COPD, failure to respond to the initial dose of a beta-2 agonist (e.g. nebulised salbutamol) is also an indication for considering hospitalisation, as is a history of a previous near-fatal attack – regardless of the severity of the current episode. All patients with a first episode of pulmonary oedema or an acute exacerbation of a chronic problem should be admitted to hospital for further investigation and treatment.

Pneumothorax

Spontaneous pneumothorax is most common in tall, thin, fit young men (Table 4.2). It is an uncommon complication of asthma and COPD. There are some rarer causes but these are very uncommon in the community setting. If a pneumothorax is suspected the patient will need to be referred to hospital for an X-ray and further evaluation.

Table 4.2 Findings from secondary survey suggesting need for hospital admission

| Condition | Key findings |

|---|---|

| Pleural effusion | History of cancer, cardiac failure or renal failure Limited chest expansion on the affected side Dull percussion note over the affected area Reduced breath sounds, TVF and vocal resonance over the affected area Possible pleuritic rub (infection) Tracheal shift away from the effusion (late sign) |

| Pneumothorax (most spontaneous pneumothoraces occur in tall, thin, fit young adults) | Sudden onset of dyspnoea and pleuritic chest pain (early sign) Development of tension pneumothorax may be identified by increasing dyspnoea, and: Reduced chest expansion on the affected side Hyper-inflated, fixed chest wall on the affected side Surgical emphysema (rare) Trachea deviated away from affected side Chest hyper-resonant to percussion Decreased or absent breath sounds on the affected side Raised JVP Deteriorating cardiovascular status (late sign) |

| Lung collapse (bronchial obstruction) | Dyspnoea Reduced chest expansion on affected side Tracheal deviation towards side of collapse Dull to percussion over non-inflated area Decreased TVF over affected area Breath sounds absent or decreased over affected area; increased bronchial breathing elsewhere |

| Pulmonary embolism (PE) | Clinical features compatible with PE: (a) Dyspnoea and/or (b) Tachypnoea (> 20 breaths per minute) and (c) Haemoptysis and/or (d) Pleuritic chest pain Major risk factors for PE: (a) Major abdominal or pelvic surgery (b) Hip or knee replacement (c) Post-operative intensive care (d) Late pregnancy (e) Caesarean section (f) Puerperium (g) Lower limb fracture (h) Varicose veins (i) Abdominal, pelvic, or metastatic malignancy (j) Reduced mobility due to hospitalisation or institutional care (k) Previous history of venous thromboembolism In the absence of another reasonable clinical explanation for the signs and symptoms: If (a), (b) and (c) are all confirmed the likelihood of PE is high; If (a) and (b) or (c) are present the likelihood of PE is intermediate; If (a) is present but (b) and (c) are both absent the likelihood of PE is low, especially in cases of pleuritic chest pain or haemoptysis not accompanied by breathlessness |

Pulmonary embolism

Half of all patients suffering pulmonary embolism will develop the condition whilst in hospital or long term care. The remainder will have an unknown aetiology or will have been exposed to a known risk factor (see Table 4.2). If a pulmonary embolism is suspected the patient will require urgent transfer to hospital for possible heparinisation or thrombolysis.5

Treatment and disposal (plan)

The initial out-of-hospital treatment of each of the four key conditions is given in Table 4.3 and Boxes 4.12 to 4.14. Interventions recommended in the JRCALC guidelines for paramedic use are asterisked.6

| Moderate acute asthma | Severe acute asthma (or no response to treatment in moderate asthma) | Life threatening acute asthma |

|---|---|---|

| Protect and maintain airway as necessary | Oxygen via non-rebreathing mask* | Oxygen via non-rebreathing mask* |

| Position for comfort (usually sitting upright) | Give salbutamol 5 mg nebuliser* | Give salbutamol 5 mg nebuliser mixed with ipratropium 0.5 mg* |

| Salbutamol 5 mg via oxygen driven nebuliser | Administer prednisolone 40–50 mg orally or hydrocortisone 100 mg IV* | Commence transportation to hospital |

| If PEFR >50–75% of normal, give prednisolone 40–50 mg orally | If no response, give salbutamol 5 mg nebuliser mixed with ipratropium 0.5 mg* | Administer prednisolone 40–50 mg orally or hydrocortisone 200 mg IV* |

| Treat and leave if patient responds to treatment | Give continuous salbutamol 5 mg nebulisers until symptoms are controlled | Give continuous salbutamol 5 mg nebulisers until symptoms are controlled |

| Arrange re-assessment, possibly by telephone, at a suitable time | Consider treat and leave if patient fully responds to treatment and has adequate carer support | Consider intravenous crystalloids in the presence of dehydration to limit mucous plugging |

| Consider referring to GP or specialist nurse for delayed follow-up if patient requires further support or review of treatment | If discharged, arrange re-assessment, possibly by telephone, at a suitable time | Refer to GP for immediate appointment |

Box 4.12 Treatment of COPD3

If no response to initial nebuliser, transport to hospital. On route:

Box 4.13 Treatment of acute pulmonary oedema

All patients with an acute exacerbation of pulmonary oedema require hospitalisation

Use Continuous Positive Airway Pressure ventilation (CPAP) if available; otherwise consider assisting ventilations with BVM if respiratory failure evident

Use Continuous Positive Airway Pressure ventilation (CPAP) if available; otherwise consider assisting ventilations with BVM if respiratory failure evidentBox 4.14 Treatment of pneumonia4

If no evidence of respiratory failure or severe respiratory distress, and the patient has adequate carer support and can manage normal daily activities of living (see Chapter 3):

Follow-up

Patients with an acute exacerbation of the conditions discussed in this paper but not requiring hospital admission should be advised to request further assistance if their condition deteriorates once the carer has left. Reassessment of the need for hospital admission is then mandatory.

1 BTS/SIGN. The BTS/SIGN British guideline on the management of asthma. Thorax. 2003;58(suppl 1):i1-i94.

2 Murphy R, Mackway-Jones K, Sammy I, et al. Emergency oxygen therapy for the breathless patient. Guidelines prepared by North West Oxygen Group. J Accid Emerg Med. 2001;18:420-423.

3 The British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee. Guidelines on the Management of COPD. Thorax. 1997;52(suppl 5):S1-S28.

4 The British Thoracic Society. Guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults. Thorax. 2001;56(suppl 4):iv1-iv64.

5 The British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee Pulmonary Embolism Guideline Development Group. BTS guidelines for the management of suspected acute pulmonary embolism. Thorax. 2003;58:470-484.

6 Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee. Pre-hospital Guidelines version 2.1. London: JRCALC/Ambulance Service Association, 2002.

7 National asthma campaign. How to use your inhaler, 2004. Available online: http://www.asthma.org.uk/using_your.html (5 Mar 2007)

Marsh J. Respiratory examination. In: Marsh J., editor. Crash course. History and examination. London: Mosby International, 1999.

O’Conner DJ, Jones BG. Pathology of the respiratory system. Crash course. Pathology, 2nd edn. Mosby International, London, 2002.

The British Thoracic Society website contains extensive information about respiratory illness and relevant guidelines. Available online: http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk (5 Mar 2007)

Wardle T. Respiratory emergencies. In: Greaves I, Porter K, editors. Pre-hospital medicine. The principles and practice of immediate care. London: Arnold, 1999.

25

25

110

110

2 years

2 years