Chapter 36 Short vertical scar medial thigh lift

Introduction

Lax tissues in the upper thigh can be a concern to many people, particularly where there has been significant weight loss.1 Rubbing inner thighs can cause sores and hygiene problems. The esthetic consequences of redundant skin can be a major psychological disability and destroy interpersonal relationships.

In my experience, there is an inevitable gravitational drag on tissue that is undergoing repair and if the holding suture fails and an excessive amount of “thigh lift” has been performed, then the labia majora is pulled down, causing an open introitus and a severe problem with underwear and hygiene.2 Whilst there may be a good initial result, it becomes certain that an undesirable scar occurs below the bikini line. The presence of labial skin in the inner thigh is a major disaster.

Applied Anatomy

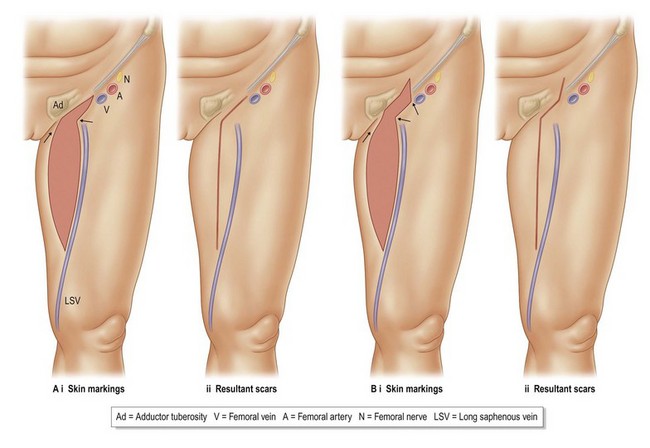

The mons pubis is held in an elevated position by fibrous suspensory attachments, but these generally loosen off with ageing and weight loss. The descent of the mons and tissues immediately above the inguinal ligament starts the cascade that results in soft tissue redundancy at a level usually at the apex of the femoral triangle. Simply lifting the mons, as occurs in some forms of abdominoplasty, can improve the appearance of the inner thigh. For a long-lasting effect though, a vertical narrowing of the base of the cone is required and this can be achieved in a number of ways (Fig. 36.1). In the tissues over the femoral triangle there are a significant number of important structures that should be maintained if possible.

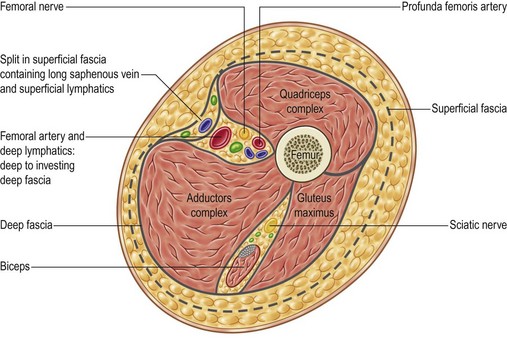

The long saphenous vein passes upwards from a point one hand’s breadth behind the medial border of the patella, to a point two fingers breadth below and two fingers breadth lateral to the pubic tubercle. The vein then turns 90° through the cribriform fascia, so joining the femoral vein at the saphenofemoral junction. The vein passes beneath the Scarpa’s fascia in its vertical ascent and is superficial to deep fascia (Fig. 36.2).

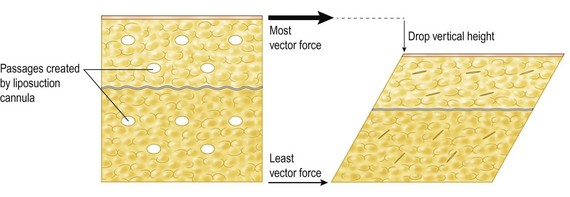

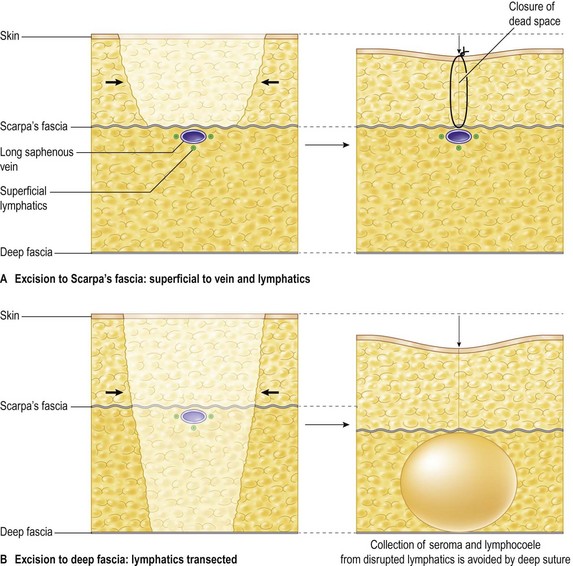

Superficial lymphatics in the thigh travel alongside the saphenous vein as trunks, before separating from the vein to enter the femoral ring and passing through a complex of lymph nodes, the most well known being Cloquet’s gland. Superficial lower leg lymph vessels follow the long saphenous vein medially and are larger and more numerous than the lower leg lateral lymphatics that pass deeply into the popliteal fossa. The medial thigh lymphatics ascend to the lower group of inguinal lymph nodes. Superficial lymphatics around the posterior thigh and buttocks pass medially and anteriorly to the front of the thigh and terminate in the upper group of inguinal nodes. By restricting the depth of resection, the undermining of tissues and the extent of the wound, there is less likelihood of lymphatic damage and subsequent collection of lymph with subsequent morbidity. The excisional plane, therefore, must be superficial to the long saphenous vein. Contrary to common procedure, it is important to preserve bulk to the thigh whilst performing the lift. For example, in the Brazilian abdominoplasty3 there is preservation of all tissues above Scarpa’s fascia and there is no incidence of seroma or lymphocele. Similarly, in the groin, if lymphatics are preserved by using lipomobilization techniques, there is no dead space available to create a problem with fluid collections in the thigh (Fig. 36.3).

If there is a minimal undermining of tissue there is no possibility of wound edge necrosis as was commonly seen after groin dissection without a 2 cm skin edge resection for malignancy.4 As the skin is approximated, the deeper tissues tighten under compression (Fig. 36.4). This will loosen eventually but still leave a better result than after a major debulking of the medial thigh tissues.

Surgical Technique

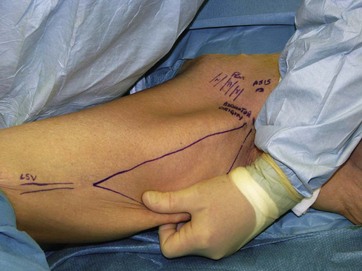

Immediately prior to surgery the patient is marked in a standing position and the problem area is addressed (Figs 36.5 and 36.6). Scars are limited in vertical length within the medial aspect of the thigh then curve anteriorly to follow the groin crease for a few centimeters, before ascending vertically again into the mons pubis in cases where there is significant mons ptosis and redundancy, the skin markings are as in Fig. 36.1. The surface marking of the long saphenous vein is noted and the proposed skin excision is marked accordingly. In the short vertical scar inner thigh lift the skin paddle excision will extend to a thigh level just distal to the apex of the femoral triangle. Variances to the scar are created by several choices of design in the skin paddle excisions. In general, a horizontal groin crease scar will drop and widen unless there is a vertical element above it, or if the horizontal scar can be restricted. Not all vertical scar thigh lifts require an extension into the mons pubis.

Skin Marking: Erect and Supine Positions

1. Mark from the adductor tuberosity to the medial condyle of the knee, vertically.

2. Surface mark the course of the long saphenous vein.

3. Using the palm of the hand, slide the soft tissue situated posterior to this line anteriorly and re-mark the vertical. The apex of the marked triangle should only extend 1.5 hand’s breadth below the adductor tuberosity.

4. Using the palm of the hand, slide the tissues anterior to this vertical line posteriorly with a slight upward elevation. Re-mark the vertical.

5. The patient lies supine. The breadth of the skin ellipse marked is equalized and made symmetrical to the opposite side.

6. An oblique line is drawn along the groin crease and the potential dog-ear is marked for excision. In cases of excessive skin redundancy a vertical line continues into and lateral to the pubic hairline of the mons. Further skin markings to plan the excision of redundant skin, the sliding advancement of the skin edges with no undermining, and comfortable skin closure are added.

The patient is supine on the operating table with full exposure of groins and thighs to knees; skin preparation is with BetadineTM and spirit. A “frog-leg” position (Fig. 36.7) is adopted for the surgery but both thighs are kept potentially mobile to assess symmetry of scars. Thromboembolic stockings, warming blankets and FlotronsTM are used. The original skin markings, from the erect position, may be modified in the GA supine frog leg position (Figs 36.8–36.10). Incisions are made in the skin to mid-dermal level, closely following the skin marking. Angles and junctions are marked to align the wound edges symmetrically. The dermis and underlying fat in the layers superficial to Scarpa’s fascia are elevated and put under traction, thence dissecting with electrocautery. Using traction and counter-traction forces, the dissection is easy and leaves the intact long saphenous vein and lymphatics. After reflecting the composite tissues, the wound is repaired by closing the space superficial to Scarpa’s fascia, using 2-0 and 4-0 Vicryl PlusTM (Fig. 36.11). By catching (quilting) the Scarpa’s layer in the wound depths, all dead spaces are closed (Fig. 36.4). Tissues are therefore bulked, effectively causing a skin tightening maneuver. In the event of excessive tightness in closure, gentle lipomobilization techniques, using PAL technology, can help mobilize the tissues and aid in closure. Eventually all the premarked areas are excised. Except in very thin-skinned people, where staples may help, all wounds are carefully closed in layers, and dead spaces eradicated. To achieve and maintain a vertical lift, in addition to the circumferential tightening, it is important to “hitch stitch” the Scarpa’s fascia to the fascia immediately over the proximal adductor origin. The adductor tubercle must not be caught by the stitch and the adductor muscle must be unviolated. Exposure to the adductor fascia is via a small pocket direct dissection, breaking open the Scarpa’s fascia to allow a 2-0 ProleneTM, or 2-0 EthibondTM, suture to grip and maintain the lift. An intradermal subcuticular 5-0 Vicryl PlusTM closes the skin edges (Figs 36.12 and 36.13), and DermabondTM or PrineoTM tape (EthiconTM), with or without Steri-stripsTM and loose dressings (i.e., not taped), are used to occlude the sutured wound. Local anesthetic may be used for postoperative pain relief but the experienced anesthetist is invaluable in providing the correct environment for patient safety and comfort postoperatively. Blood loss should be minimal and the excision is continued as the wound is closed. The emphasis is on closing and plicating the spaces above Scarpa’s fascia. No drains are required. Even at 3 months some scars can be very acceptable (Figs 36.14–36.16) and complications are rare.

Optimizing Outcomes

2. Mark standing and lying supine, with full exposure of external genitalia and nurse chaperone.

3. Starting distally, excise redundant tissue and suture the wounds as the operation proceeds in a proximal direction.

4. At the apex of the excision go slightly deeper and excise a subcutaneous “cuff” to avoid a “dog-ear” in closing.

5. Excise only to Scarpa’s fascia and excise by the “traction and counter-traction” technique.

6. Close the dead space by deep quilt suturing and inverted knots. Use monofilament ProleneTM or braided EthibondTM. If any infection risks, use Vicryl-PlusTM 2-0 or 4-0 or 5-0.

7. Hitch the Scarpa’s fascia to the fascia below the adductor origin.

8. If there is significant skin redundancy elect to use a short horizontal scar and advance the wounds vertically to excise tissue within the mons pubis.

9. Antithrombotic therapy, early mobilization, pressure garment support.

12. Scar control measures: Topical silicone gel therapy; suggest optional manual lymphatic drainage techniques.

Complications and Their Management

Infection

Superficial cellulitis – Antibiotics. Metronidazole and cefuroxime until microbiology is known. The most likely organism, within the first week, is Staphylococcus aureus, but thereafter mixed flora and later Gram-negative bacteria are the main culprits. The area is potentially heavily contaminated. BetadineTM applied topically to the wounds assists in the control of superficial sepsis.

Deeper tissue infection – An abscess requires drainage via a reasonably generous incision through the healing wound, or simply blunt penetration of the thinning tissue over the abscess will give early relief of symptoms, and reduce the risk of septicaemia and venous thrombosis.

Wound Dehiscence

Minor – This is usually secondary to poor surgical technique, with comparative tissue hypoxia encouraging sepsis and tissue breakdown. Suture knot infection does occur, particularly with braided sutures. These may settle with the use of antibiotics and topical BetadineTM or InadineTM dressings. Twice daily showers and “drying” of the wound using a hairdryer, followed by InadineTM or an absorbent dressing will be needed for some weeks.

Major – This is a disaster and is often accompanied by a state of relative malnutrition, with poor wound healing. Initially, the large wounds should be managed conservatively until the edges of the wound show re-epithialization, and then an attempt at closure, using excision and local flap or partial thickness skin graft, may speed up the healing process.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful to David Head for his invaluable assistance in preparing this chapter.

1 Hurwitz DJ. Approach to the medial thigh after weight loss. In: Rubin PJ, Matarasso A. Aesthetic Surgery after Massive Weight Loss. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:113–130.

2 Heden P. Plastic Surgery and You. Stockholm: Silander and Fromholtz Forlags; 2003. p. 219–22

3 Graf R, de Araujo LR, Rippel R, et al. Lipoabdominoplasty: Liposuction with reduced undermining and traditional abdominal skin flap resection. Aesth Plast Surg. 2006;30(1):1–8.

4 Vordermark JS, Jones BM, Harrison DH. Surgical approaches to block dissection of the inguinal lymph nodes. JPRAS. 1985;37(3):321–325.