Short Face Growth Patterns

Maxillomandibular Deficiency

• Treatment Indications and Objectives

• The Role of Growth Modification in the Preadolescent Patient

• Postsurgical Orthodontic Maintenance and Detailing

• Complications, Informed Consent, and Patient Education

• Malocclusion after Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

• Temporomandibular Disorders: The Effects of Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

A frequently seen pattern of facial disharmony has the common denominator of a significant degree of vertical and horizontal (sagittal) deficiency in the maxilla and mandible. Measuring the ratio of the lower facial height (i.e., the subnasion to the menton) to the upper facial height (i.e., the glabella to the subnasion) will confirm that the lower height is diminished. The height of the alveolar process in both jaws is reduced.23 The visual presentation of the face includes an apparent redundancy of the soft-tissue envelope of the lower face, thereby creating “chubby cheeks” in the adolescent and a prematurely aged look by early adulthood.

Clinical examination of the individual with a short face growth pattern will generally confirm a pseudoprominence of the nose; an acute nasolabial angle; a measurable and visually perceived short lower facial height with a disproportionate facial width-to-height ratio; and either a prominent pogonion (more frequent with a Class I deep bite) or a weak chin (more common with a Class II excess overjet).3,10,11,20,21,35,39,40 Normally, there is a 1 : 2 relationship between the distance from the base of the nose to the upper lip and the distance from the lower lip to the chin. In the individual with a short face growth pattern, the relationship is closer to 1 : 1.15,42,43,56 The labiomental sulcus is deep and the lower lip is everted, thereby further confirming the degree of mandibular deficiency. The maxillary incisors are often completely covered by the upper lip, which creates an edentulous appearance in repose and an unfavorable “no gingiva” smile. With the teeth in occlusion, the oral aperture appears closed and the upper lip projects forward, often in front of procumbent incisors. Individuals are frequently described as having a sad or unhappy look in repose as a result of the downturned oral commissures and the closed aperture. The reduced lower facial height causes the everted and prominent lips that would otherwise have appropriate shape and volume if the facial height and horizontal projection of the jaws were restored. In the profile view, the nose appears long and prominent. There is often a lateral flaring of the nostrils with a “hanging columella.”

Classically, there is a deep bite with either marked anterior crowding or excessive flaring with less dental crowding.34 There may be a Class II malocclusion with greater than average overjet.50,51 If so, the mandible has greater deficiency than the maxilla, and the pogonion will lack prominence. Individuals with Class I deep bite without excess overjet are more likely to have a retropositioned A-point as compared with the B-point (i.e., a counterclockwise rotated maxillomandibular complex) and a prominent pogonion. The maxillary and mandibular planes are often nearly horizontal, which results in a “square jaw” facial appearance.

Functional Aspects

• Articulation errors in speech and altered swallowing mechanisms that result from the small jaws, the Class II deep-bite malocclusion, and the limited intraoral volume for the tongue are expected (see Chapter 8).

• Difficulties with chewing and with lateral and protrusive mandibular movements as a result of the Class II deep-bite malocclusion are expected (see Chapter 8).

• A spectrum of upper airway sites of obstruction often exists with the short face growth pattern. This includes obstructions at the intranasal, palatopharyngeal (retropalatal), and glossopharyngeal (retroglossal) locations. The incidence of obstructive sleep apnea is increased in this patient population and should be ruled out (see Chapter 10 & 26).

• Detrimental long-term effects on the dentition and the periodontium as a result of any traumatic malocclusion, the crowding of the teeth in the limited alveolar housing, and previous camouflage orthodontic treatment may be seen (see Chapter 5 & 6).

• A higher incidence of temporomandibular disorders in the form of masticatory muscle discomfort as a result of the short facial height and the deep-bite malocclusion has been reported (see Chapter 9).

Clinical Characteristics

• Absence of maxillary tooth show beneath a relaxed upper lip

• Limited tooth and no gingiva show with broad smile

• An apparent fullness of the cheeks and a squareness of the overall face

• An apparent prominent and elongated nose when viewed in profile

• Procumbent everted lips, turned down corners of the mouth, and a closed aperture

• An excessively deepened and elongated labiomental fold

• Soft-tissue bunching that eventually results in perioral creases (i.e., marionette lines)

• Early and deep jowl formation by middle age

• Premature loss of any semblance of an attractive neck–jaw angle

Radiographic Findings

• The total anterior facial height is decreased (i.e., from the nasion to the menton).

• The lower anterior facial height is short (i.e., from the subnasion to the menton).

• Horizontal retrusion is measurable at the A-point and the B-point in both jaws.

• Disproportion in the ratio of the facial width to the facial height is measurable on an anteroposterior cephalometric radiograph or a computed tomography scan.

• Excessive procumbency of the maxillary and mandibular incisors is frequently measurable.

• Excessive flattening (i.e., counterclockwise rotation) of the maxillary and mandibular planes is frequently measurable.

• Decreased alveolar bone height associated with the maxillary incisors is measurable (i.e., the distance from the floor of the nose to the incisal edge).

• Decreased alveolar bone height associated with the mandibular incisors is measurable (i.e., the distance from the short menton to the incisal edge).

Treatment Indications and Objectives

The indications for treatment in a patient with a short face growth pattern may be to improve function (e.g., occlusion, chewing, swallowing, speech, breathing, lip posture), but another compelling aspect is typically the enhancement of facial aesthetics. The visually aesthetic advantages of the surgical lengthening and projection of the short and retrusive lower face toward Euclidian proportions are immediately apparent and do not require quantification.32,33,58

To restore facial proportions and preferred facial aesthetics, there must be both vertical and horizontal expansion of the maxillomandibular complex.54 Accomplishing these objectives will eliminate cheek and lip region bunching and distortion and restore a pleasing soft-tissue envelope. When this is done, a youthful oral aperture is restored. The corners of the mouth are no longer downturned, and the lips will be separated when they are at rest. The upper vermillion increases in volume, and the labiomental fold flattens. The maxillary incisors can be seen in repose, and the gingiva is visible with smile. The nose no longer appears excessively prominent, and the nasolabial angle improves. The jowls diminish, and the length-to-width ratio of the face is restored. The shape of the face changes from square to oval with the restoration of the natural contours and attractive ogee curves. The overall facial aesthetic changes from sad and older appearing to younger looking and more attractive (Figs. 23-1 through 23-7).

Figure 23-1 A 28-year-old woman arrived for a third surgical opinion regarding a reduction rhinoplasty and reduction genioplasty. The diagnosis of a short face growth pattern was made. Maxillomandibular advancement and vertical lengthening were recommended. The patient agreed to a surgical approach with perioperative orthodontics. Her surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (vertical lengthening, horizontal advancement, arch expansion and clockwise rotation) with interpositional grafting; sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and clockwise rotation); and osseous genioplasty (vertical lengthening) with interpositional grafting. A, Frontal views in repose before and after reconstruction. B, Frontal views with smile before and after reconstruction. C, Oblique facial views before and after reconstruction. D, Profile views before and after reconstruction. E, Occlusal views before and after treatment. Only minimal change in the occlusion was required. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

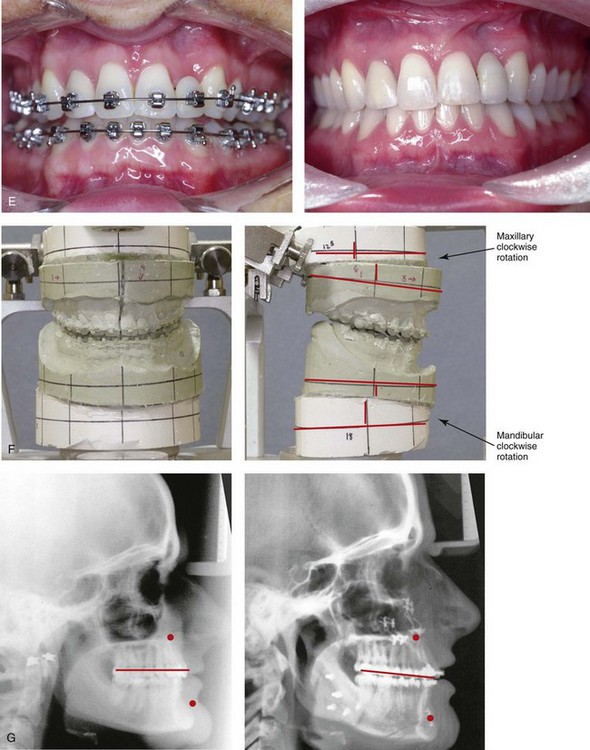

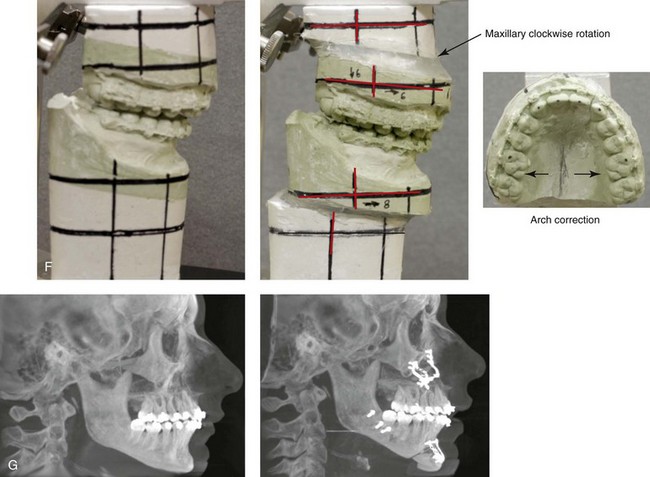

Figure 23-2 A 16-year-old girl arrived with her parents for surgical evaluation. She requested a reduction rhinoplasty and a chin implant. A diagnosis of maxillomandibular deficiency with a Class II excess overjet malocclusion was made. She agreed to a surgical and (redo) orthodontic approach. No extractions were carried out, and a degree of incisor proclination was tolerated. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement, vertical lengthening, and clockwise rotation) with interpositional grafting; sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and clockwise rotation); and osseous genioplasty (vertical lengthening) with interpositional grafting. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before and after treatment. Only minimal change in the occlusion was required. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

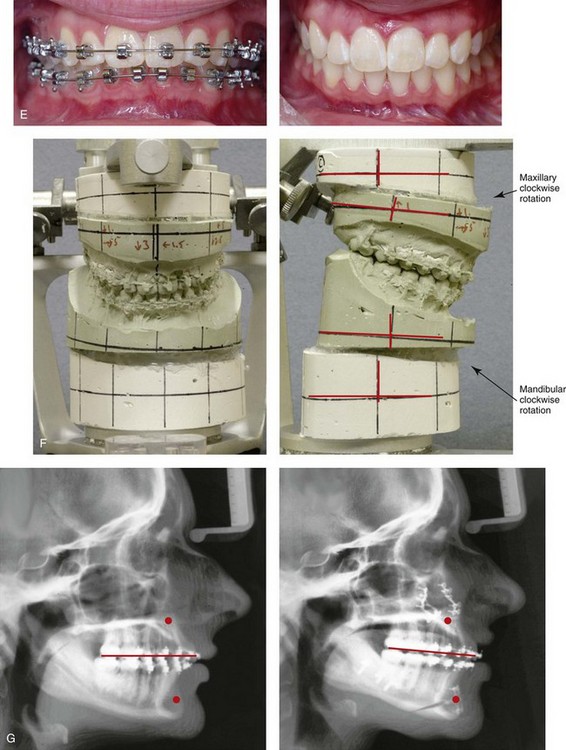

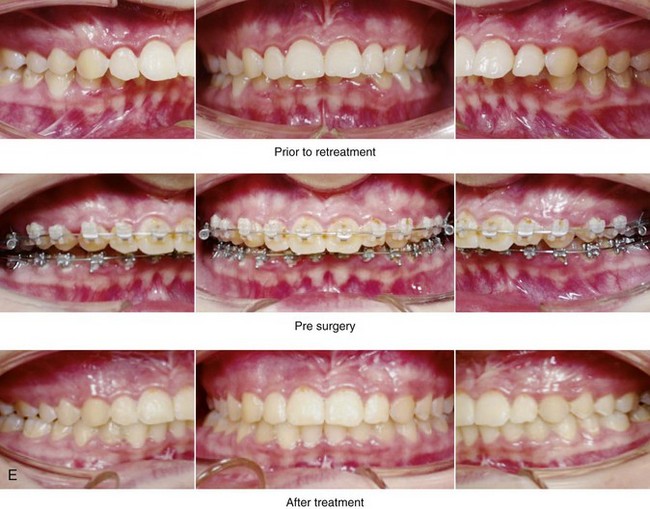

Figure 23-3 A 24-year-old woman arrived for evaluation. She had previously undergone four bicuspid extractions and orthodontics to neutralize her occlusion during her high school years. Analysis confirmed a short face growth pattern that accounted for the apparent large nose, weak profile, obtuse neck–chin angle, and edentulous look. She agreed to a combined (redo) orthodontic and surgical approach. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement, vertical lengthening, and clockwise rotation) with interpositional grafting; sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and clockwise rotation); and osseous genioplasty (vertical lengthening and minimal horizontal advancement) with interpositional grafting. Minimal change in the occlusion was required. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, with orthodontics in progress, and after reconstruction. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

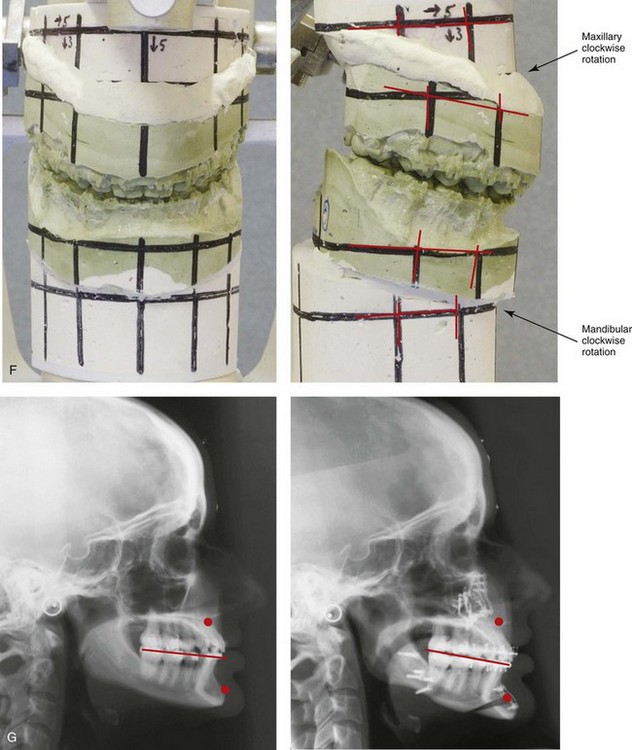

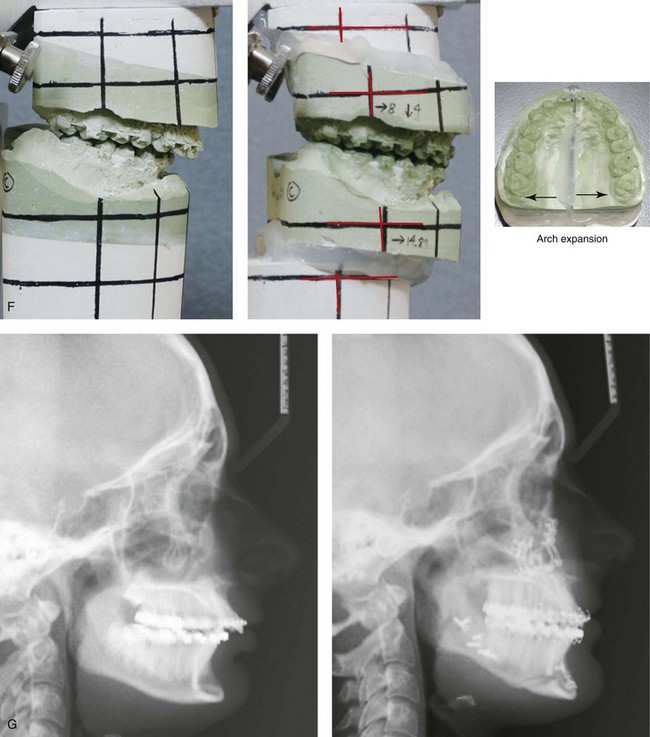

Figure 23-4 A woman in her late 20s arrived for the evaluation of her edentulous look. She had previously undergone orthodontic neutralization of her occlusion during her high school years. Analysis suggested a short face growth pattern that accounted for her apparent large nose, protrusive chin, and edentulous look. The patient also complained of nasal obstruction, restless sleeping, and daytime fatigue. Examination confirmed septal deviation and enlarged inferior turbinates, and an attended polysomnograph documented mild obstructive sleep apnea. She underwent a combined (redo) orthodontic and surgical approach. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, vertical lengthening, arch expansion and clockwise rotation) with interpositional grafting sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and clockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical lengthening and minimal horizontal advancement) with interpositional grafting; and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, with orthodontics in progress, and 1 year after reconstruction. Minimal change in the occlusion was required. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

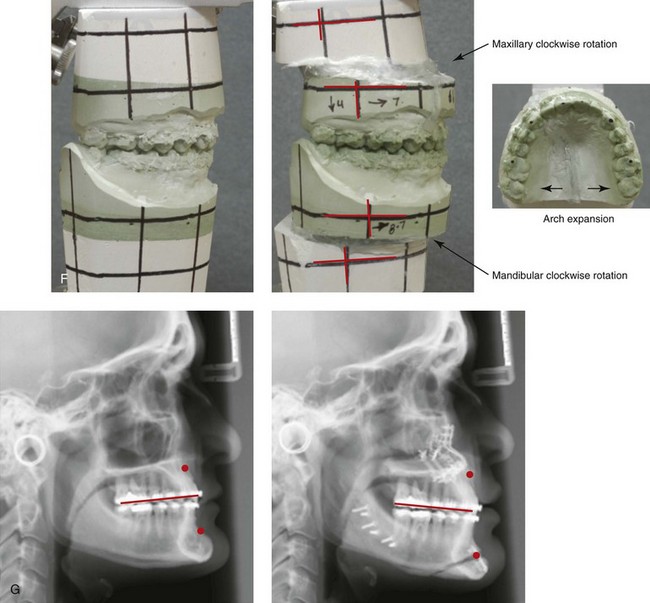

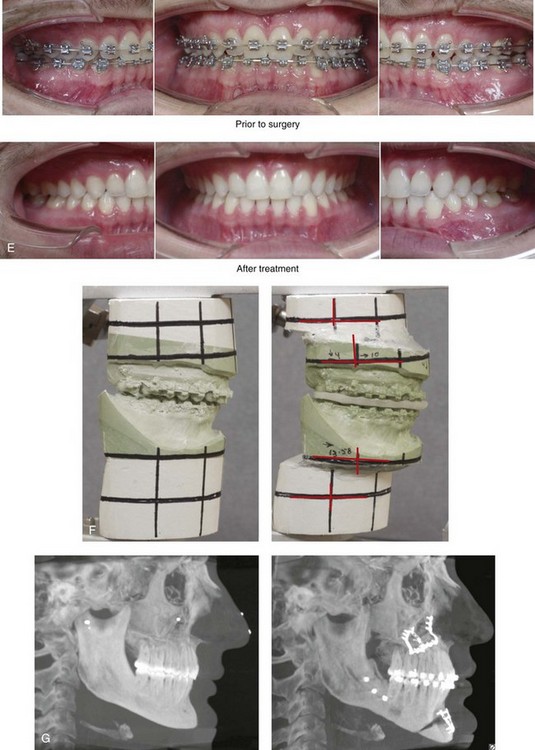

Figure 23-5 A 16-year-old girl was referred by her orthodontist, primarily for the evaluation of malocclusion. She underwent attempts at growth modification and then orthodontic treatment when she was between 10 and 12 years old. The examination confirmed maxillomandibular deficiency with a Class II excess overjet malocclusion. She had chronic nasal obstruction, and she was also found to have a deviated septum and hypertrophic inferior turbinates. A surgical and (redo) orthodontic approach was recommended. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, vertical lengthening, and arch expansion) with interpositional grafting; sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement) osseous genioplasty (vertical lengthening) with interpositional grafting; and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, with orthodontics in progress, and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

Figure 23-6 A man in his mid 20s arrived for the surgical evaluation of an edentulous look and difficulty breathing. He was found to have a short face growth pattern, nasal obstruction, and mild obstructive sleep apnea. A surgical approach with (redo) orthodontics was recommended. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy (horizontal advancement, vertical lengthening, and clockwise rotation) with interpositional grafting; sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement and clockwise rotation); osseous genioplasty (vertical lengthening) with interpositional grafting; and septoplasty and inferior turbinate reduction. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before and after treatment. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

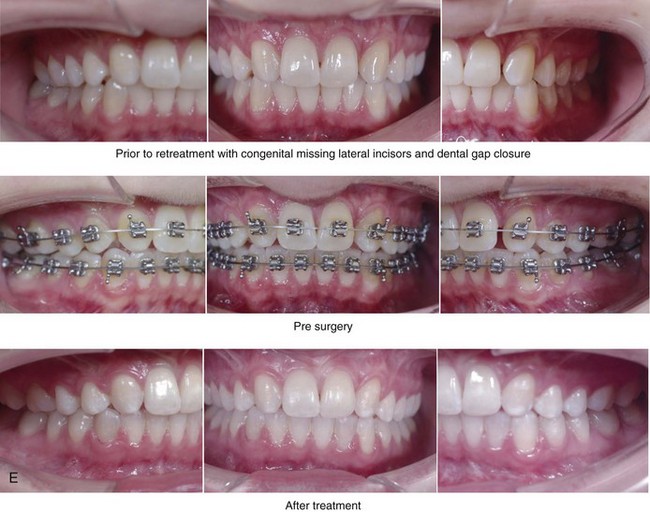

Figure 23-7 A 26-year-old woman with a short face growth pattern arrived to discuss her maxillofacial issues. During her early teenage years, she underwent a full course of orthodontics. Her maxillary lateral incisors were congenitally absent, and the spaces were orthodontically closed, partially by tipping the canines forward. The maxillary incisor root resorption was significant. There was crowding in the mandibular arch with a degree of procumbency. The patient had an interest in improving her weak profile and her edentulous look. The patient’s history confirmed heavy snoring, restless sleeping, and daytime fatigue. Examination confirmed a deviated septum and hypertrophic inferior turbinates. Maxillary retrusion resulted in the close proximity of the soft palate to the pharyngeal wall. A retrusive mandible resulted in the close proximity of the tongue to the posterior pharyngeal wall. An attended polysomnogram confirmed mild obstructive sleep apnea. Evaluation by a periodontist and an orthodontist confirmed the advantage of a comprehensive approach to improve the airway, to achieve a more balanced facial appearance, and to improve long-term periodontal health. A trial of continuous positive airway pressure improved daytime alertness, but the patient’s feelings of claustrophobia prevented its use. Periodontal evaluation with gingival grafting and maintenance was carried out. Orthodontic appliances were placed with limited dental repositioning of the maxillary incisors as a result of baseline root resorption. The patient’s surgery included maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy in segments (horizontal advancement, vertical lengthening, arch form correction, and clockwise rotation) with interpositional graft; bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies (horizontal advancement); and osseous genioplasty (vertical lengthening) and limited horizontal advancement) with interpositional bonegraft. As a result of treatment, the patient has had a relief of her snoring, more restful sleeping, and improved alertness during the day. A, Frontal views in repose before and after treatment. B, Frontal views with smile before and after treatment. C, Oblique facial views before and after treatment. D, Profile views before and after treatment. E, Occlusal views before retreatment, with orthodontics in progress, and 1 year after reconstruction. Minimal change in occlusion was required. F, Articulated dental casts that indicate analytic model planning. G, Lateral cephalometric radiographs before and after treatment.

The Role of Growth Modification in the Preadolescent Patient

Individuals with lower anterior facial height deficiency can frequently be identified at an early age. They tend to have an acute (flat) mandibular plane angle with a deep bite.25 This is accompanied by an upward (counterclockwise) rotated anterior mandible that results in a prominent-appearing pogonion.

Orthodontic growth modification treatment during preadolescence attempts to increase the eruption of the posterior teeth.19,31,44 If this is successful, while lengthening the anterior facial height, this will cause the mandible to rotate clockwise, thereby resulting in a downward and backward shift at the pogonion. Unfortunately, this backward rotation of the mandible is not favorable to the profile unless it is also accompanied by horizontal advancement. For the preadolescent with a Class II excess overjet and a short face growth pattern, cervical headgear has been used to apply extrusion forces to the posterior maxillary dentition; however, this tends to simultaneously “set back” the already retrusive maxilla. As an alternative, functional intraoral appliances have also been tried in an attempt to erupt the posterior dentition. These orthopedic maneuvers, when followed by orthodontic mechanics, may achieve a neutralized occlusion in the child with maxillomandibular deficiency. However, this treatment cannot achieve the vertical height and the horizontal projection required to normalize the facial proportions and improve the airway.4,7,22,52,59

Since the late 1970s, Delaire and colleagues have attempted to achieve horizontal advancement and vertical lengthening of the maxilla with a face mask apparatus.6 The best data indicate that use of the Delaire mask to increase maxillary projection is only effective for young children who are less than 8 to 10 years old, when the sutures remain open.48,49 Unfortunately, with the short face growth pattern, Delaire face mask therapy is simultaneously counterproductive on the baseline deficient mandible, even if it effectively projects the maxilla.

Definitive Reconstruction

Timing of Orthognathic Surgery

The best evidence available indicates that, when orthognathic surgery is performed on a patient with a short face growth pattern (i.e., maxillomandibular deficiency) as early as the completion of the adolescent growth spurt, the result will be stable from a growth perspective. Further sagittal growth of either the maxilla or the mandible almost never occurs.45 Vertical growth in both the mandible and the maxilla is also not likely to continue, but, if it does, it should be proportionate. Therefore, proceeding with orthognathic surgery in the individual with maxillomandibular deficiency as early as the age of 13 or 14 years—but only after the eruption and orthodontic alignment of the teeth—is generally safe from a growth perspective.

Orthodontic Preparation for Orthognathic Surgery

Class II, Division I

• Compatible intercanine widths either through orthodontics alone or with the help of maxillary segmental osteotomies

• Bonding or banding and leveling of the first and second molars

• Anticipating similar maxillary and mandibular arch forms either through orthodontics alone or with the help of maxillary segmental osteotomies

Basic Surgical Approach

By definition, for the patient with a moderate to severe short face growth pattern, there will be a need to simultaneously surgically reposition the maxilla, the mandible, and the chin region if the normalization of both the facial height and the facial projection is desired.1,2,5,8,9,27–30,36–41,53,58 For the patient with a Class I short face growth pattern, simply lengthening the maxilla to improve the upper lip to tooth relationship through Le Fort I osteotomy with maintenance of the occlusion will cause an undesirable backward rotation of the mandible. This “single jaw” approach prevents the necessary horizontal advancement of the maxillomandibular complex. Unfortunately, the inability to achieve adequate sagittal (horizontal) projection of the maxillomandibular complex is likely to result in aesthetic disappointment. For this reason, bimaxillary surgery (i.e., Le Fort I and bilateral sagittal split ramus osteotomies) is required for the correction of a short face growth pattern. In borderline cases, a limited camouflage approach involving an osseous genioplasty with significant vertical lengthening and a degree of horizontal advancement may at least provide some aesthetic enhancement without introducing surgical deformity (see Chapters 37 and 40).

Orthognathic planning begins with the making of decisions about the magnitude of vertical lengthening, horizontal advancement, and clockwise rotation required in the maxilla. These decisions are primarily based on aesthetic judgments that are made when examining the patient in the natural head position (see Chapter 12). A common mistake is to err on the side of insufficient lengthening of the midface out of a belief that the short upper lip will not accommodate the skeletal lengthening. Experience has shown that the hypotonic (short) upper lip will stretch and gain function when the maxilla is surgically expanded (i.e., horizontal advancement and vertical lengthening). In addition, as the maxilla is surgically lengthened and simultaneously advanced and clockwise rotated, the pyriform rims and the anterior nasal spine are thrust forward and inferiorly, thus further stretching and filling out the soft tissues of the lower aspect of the nose and the upper lip. When the anterior floor of the nose (i.e., the alveolar bone height above the incisors) is short, consideration should also be given to graft augmentation of the anterior floor at the rim just above the incisors to further improve nasal base aesthetics. The need for this should be definitively reassessed during the operation, after the maxilla is stabilized with plate and screw fixation in its new location. In addition to maxillary reconstruction, the mandible requires horizontal advancement and often clockwise rotation. This is accomplished through sagittal split ramus osteotomies. In most cases, an osseous genioplasty provides access to vertically lengthen the deficient anterior mandibular alveolar height and interpositional grafting is required. Horizontal advancement of the chin is not generally beneficial.

The previous line of thinking was that vertical lengthening, especially in combination with horizontal advancement of the maxilla, is unstable and inadvisable.5,13,14,17,18,24,46,57 We now know that, with full mobilization of the down-fractured maxilla, lengthening and advancement can be carried out with occlusal stability and the routine achievement of improved facial aesthetics. This requires the following: 1) well-designed and executed osteotomies; 2) the full mobilization of the down-fractured maxilla; 3) rigid plate and screw fixation; 4) the placement of an interpositional graft (e.g., autogenous or allogenic corticocancellous iliac bloc graft) into the gaps between the zygomatic buttress and the pyriform rim on each side; 5) additional rigid plate and screw fixation to secure each graft; and 6) appropriate postoperative management to control bite forces during the early healing phase at the Le Fort I osteotomy sites (see Chapter 15). Kretschmer and colleagues studied the incidence of relapse after Le Fort I osteotomy with vertical lengthening with both single piece and segmental Le Fort I osteotomies (see Chapter 17).16 The authors’ data confirms that, when significant advancement and lengthening at the Le Fort I osteotomy site are carried out, key factors to achieve postoperative stability include the interpositional bone grafting of defects and rigid plate and screw fixation. Interestingly, the researchers did not find segmentation of the maxilla during bimaxillary procedures to be a significant cause of either skeletal or dental relapse.

Immediate Presurgical Planning

The patient’s specific medical and dental records are reviewed, including radiographs (e.g., computed tomography scans; panoramic, lateral, and posteroanterior cephalometric radiographs; periapical images); photographs (facial and occlusal); and dental models. Immediate presurgical records (i.e., within 2 to 6 weeks of surgery) will most importantly include facial measurements obtained from direct visual examination; alginate impressions of the maxilla and mandible; an accurate centric relation bite registration; and face-bow registration. First, broad-stroke decisions are made regarding the preferred vector changes for each jaw; only then can the precise millimeter distances and angular changes required for each jaw to achieve the desired result be determined (see Chapter 12). Analytic model planning is carried out on the articulated dental casts with use of the Erickson Model Table. Splints are constructed to assist with the achievement of the precise occlusion and preferred facial aesthetics in the operating room (see Chapter 13).

Complications, Informed Consent, and Patient Education

The orthodontist and the surgeon are asked to evaluate the individual with maxillomandibular deficiency and to then attempt to alter nature’s events. By understanding the expected effects of the uncorrected short face growth pattern (i.e., airway, aesthetics, long-term dental health) and with knowledge of how specific orthodontic and orthognathic interventions will alter head and neck function and enhance facial aesthetics, a successful outcome is expected in most cases. An understanding of the potential risks in comparison with the anticipated benefits of each intervention is taken into account, because complications and dissatisfaction will always occur in a small percentage of individuals. The clinician’s ability to communicate the potential risks, complications, alternative approaches, and benefits of the recommended treatment to the patient and their family is essential. The patient’s informed decision to proceed provides the basis for shared responsibility of the expected convalescence and long-term outcome (see Chapter 16).

Malocclusion after Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

There are inherent biologic challenges to the orthodontic movement of teeth within the alveolar process and the surgical repositioning of the jaws or jaw segments after osteotomies in a patient with a short face growth pattern. This includes the technical aspects of the repositioning; the initial healing requirements; and the difficulties associated with the long-term maintenance of the relocated teeth, jaws, and jaw segments. When following sound biomechanical and aesthetic principles, clinicians carry out orthodontic treatment and surgical procedures that involve correction and then successful maintenance of the result in most cases. Potential intraoperative technical difficulties associated with sagittal split ramus osteotomies of the mandible and with maxillary Le Fort I osteotomy can result in immediate (early) malocclusion, but this is preventable in most cases. Ongoing growth after surgery is rarely an issue with a short face growth pattern. Although condylar resorption after orthognathic surgery is not entirely predictable, it is uncommon (see Chapter 36). The orthodontic removal of dental compensations and the placement of the teeth solidly in the alveolar housing will best ensure a long-term stable occlusion and periodontal health. All of these factors are taken into account to achieve and then maintain a favorable result (see Chapter 17).

Temporomandibular Disorders: The Effects of Orthodontics and Orthognathic Surgery

It is estimated that an average of 32% of the population reports at least one symptom of temporomandibular disorder, whereas an average of 55% demonstrate at least one clinical sign. Temporomandibular disorder includes various symptoms and signs of the temporomandibular joints, the masticatory muscles, and the related structures. The symptoms and signs may include a spectrum of referred head and neck pain; joint noise (e.g., popping, clicking, crepitus); reduced or altered mandibular movements (i.e., muscle spasm or disc displacement with or without reduction); condylar head erosion; and pain on direct palpation of either temporomandibular joint or of the masticatory muscles. Occlusal factors (i.e., degrees of malocclusion) are often claimed to be associated with temporomandibular disorders. Interestingly, patients with maxillomandibular deficiency (i.e., the short face growth pattern) tend to have higher maximum biting forces than those with normal or long vertical facial dimensions.12,26,47,55 This has been documented to be statistically significant during swallowing, simulated chewing, and maximum biting.31 Affected patients often claim to have difficulty chewing through foods and also experience masseter muscle discomfort. The individual with a short face growth pattern and a Class II significant overjet malocclusion is likely to have an uncomfortable dual bite, whereas the patient with a Class I deep bite is more likely to have temporomandibular joint clicking; in the latter case, there is no reason to believe that progressive temporomandibular joint pathology will occur (see Chapter 9).

References

1. Bell, WH. Correction of the short-face syndrome-vertical maxillary deficiency: A preliminary report. J Oral Surg. 1977; 35:110.

2. Bell, WH, Jacobs, JD, Legan, HL. Treatment of Class II deep bite by orthodontic and surgical means. Am J Orthod. 1984; 85:1–20.

3. Blanchette, M, Nanda, R, Currier, G, et al. A longitudinal cephalometric study of the soft tissue profile of short- and long-face syndromes from 7 to 17 years. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1996; 109:116–131.

4. Burstone, CR. Deep overbite correction by intrusion. Am J Orthod. 1977; 72:1–22.

5. de Mol van Otterloo, JJ, Tuinzing, DB, Kostense, P. Inferior positioning of the maxilla by a Le Fort I osteotomy: A review of 25 patients with vertical maxillary deficiency. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1996; 24:69.

6. Delaire, J, Verdon, P, Lumineau, J, et al. Quelques resultats des tractions extra-orales B appui fronto-mentonnier dans le traitement orthopedique des malformations maxillomandibulaires de classe III et des sequelles osseuses des fentes labio-maxillaires. Rev Stomatol (Paris). 1972; 73:633.

7. Engel, G, Cornforth, G, Damerell, JM, et al. Treatment of deep-bite cases. Am J Orthod. 1980; 77:1–13.

8. Epker, BN, Fish, LC, Paulus, PJ. The surgical–orthodontic correction of maxillary deficiency. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1978; 46:171.

9. Epker, BN, Turvey, TA, Fish, LC. Indications for simultaneous mobilization of the maxilla and mandible for the correction of dentofacial deformities. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982; 54:369.

10. Farkas, LG, Sohm, P, Kolar, JC, et al. Inclinations of the facial profile: Art versus reality. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985; 75:509.

11. Freudenthaler, JW, Celar, AG, Schneider, B. Overbite depth and anteroposterior dysplasia indicators: The relationship between occlusal and skeletal patterns using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis. Eur J Orthod. 2000; 22:75–83.

12. Hart, DL, Lundquist, DO, Davis, HC. The effect of vertical dimension on muscular strength. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1981; 3:57–61.

13. Hedemark, A, Freihofer, HP, Jr. The behaviour of the maxilla in vertical movements after Le Fort I osteotomy. J Maxillofac Surg. 1978; 6:244.

14. Hirdnaka, D, Kelly, J. Stability of simultaneous orthognathic surgery on the maxilla and mandible: A computer-assisted cephalometric study. Int J Adult Orthod Orthognath Surg. 1987; 2:193.

15. Isaacson, J. Extreme variation in vertical facial growth and associated variation in skeletal and dental relations. Angle Orthod. 1970; 71(40–41):219–229.

16. Kretschmer, WB, Baciut, G, Baciut, M, et al. Stability of Le Fort I osteotomy in bimaxillary osteotomies: Single-piece versus 3-piece maxilla. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010; 68:372–380.

17. LaBlanc, JP, Turvey, TA, Epker, BN. Results following simultaneous mobilization of the maxilla and mandible for the correction of dentofacial deformities: Analysis of 100 consecutive patients. J Oral Surg. 1982; 54:607.

18. Moser, K, Freihofer, HP. Long-term experience with simultaneous movement of the upper and lower jaw. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1980; 8:271.

19. Moss, M, Salentijn, L. Differences between the functional matrices in anterior open-bite and in deep-bite. Am J Orthod. 1971; 60:264–280.

20. Nanda, SK. Patterns of vertical growth in the face. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1988; 93:103–116.

21. Nanda, RS. Growth patterns in subjects with long and short faces. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1990; 98:247–258.

22. Nemeth, RB, Isaacson, RJ. Vertical anterior relapse. Am J Orthod. 1974; 65:565–585.

23. Nielsen, IL. Vertical malocclusions: Etiology, development, diagnosis and some aspects of treatment. Angle Orthod. 1991; 61:247–260.

24. Norholt, SE, Sindet-Pedersen, S, Jensen, J. An extended Le Fort I osteotomy for correction of midface hypoplasia: A modified technique and results in 35 patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996; 54:1297.

25. Opdebeeck, H, Bell, W. The short face syndrome. Am J Orthod. 1978; 73:499–511.

26. Piecuch, J, Tideman, H, DeKoomen, H. Short-face syndrome: Treatment of myofascial pain dysfunction by maxillary disimpaction. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1980; 49:112–116.

27. Posnick, JC, Fantuzzo, J, Orchin, J. Deliberate operative rotation of the maxillomandibular complex to alter the A-point to B-point relationship for enhanced facial esthetics. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 64:1687–1695.

28. Posnick, JC, Fantuzzo, JJ, Troost, T. Simultaneous intranasal procedures to improve chronic obstructive nasal breathing in patients undergoing maxillary (Le Fort I) osteotomy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 65:2273–2281.

29. Posnick, JC, Agnihotri, N. Managing chronic nasal airway obstruction at the time of orthognathic surgery: A twofer. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:695–701.

30. Poulton, DR. Correction of extreme deep overbite with orthodontics and orthognathic surgery. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1989; 96:275–280.

31. Proffit, WR, Sellers, KT. The effect of intermittent forces on eruption of the rabbit incisor. J Dent Res. 1986; 65:118–122.

32. Proffit, WR, Phillips, C, Dann, CIV. Who seeks surgical orthodontic treatment? Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1990; 3:153.

33. Proffit, WR, Phillips, C, Douvartzidis, N. A comparison of outcomes of orthodontic and surgical-orthodontic treatment of Class II malocclusion in adults. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1992; 101:556–565.

34. Proffit, WR, Fields, HW, Moray, LJ. Prevalence of malocclusion and orthodontic treatment need in the United States: estimates from the N-HANES III survey. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1998; 13:97–106.

35. Proffit, WR, Fields, HW, Sarver, DM. Contemporary orthodontics, ed 4. St. Louis: Mosby; 2007.

36. Reyneke, JP, Evans, WG. Surgical manipulation of the occlusal plane. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1990; 5:99–110.

37. Rosen, HM. Definitive surgical correction of vertical maxillary deficiency. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990; 85:215.

38. Rosen, HM, Ackerman, JL. Porous block hydroxyapatite in orthognathic surgery. Angle Orthod. 1991; 61:185.

39. Rosen, HM. Facial skeletal expansion: Treatment strategies and rationale. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992; 89:798.

40. Rosen, H. Aesthetics in facial skeletal surgery. Perspectives in Plastic. Surgery. 1993; 6:1.

41. Rosen, HM. Occlusal plane rotation: Aesthetic enhancement in mandibular micrognathia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993; 91:1231.

42. Sassouni, V, Nanda, S. Analysis of dentofacial vertical proportions. Am J Orthod. 1964; 50:801–823.

43. Sassouni, V. A classification of skeletal facial types. Am J Orthod. 1969; 55:109–122.

44. Schudy, FF. Vertical growth versus anteroposterior growth as related to function and treatment. Angle Orthod. 1964; 34:75–93.

45. Stahl, F, Baccetti, T, Franchi, L, McNamara, JA. Longitudinal growth changes in untreated subjects with class II division malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008; 134:125–137.

46. Stella, JP, Streater, MR, Epker, BN, Sinn, DP. Predictability of upper lip soft tissue changes with maxillary advancement. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989; 47:697.

47. Throckmorton, G, Finn, R, Bell, W. Biomechanics of differences in lower face height. Am J Orthod. 1980; 77:410–420.

48. Tollaro, I, Baccetti, T, Franchi, L. Class III malocclusion in the deciduous dentition: A morphological and correlation study. Eur J Orthod. 1994; 16:401–408.

49. Tollaro, I, Baccetti, T, Franchi, L, Tanasescu, CD. Role of posterior transverse interarch discrepancy in class II, division 1 malocclusion during the mixed dentition phase. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1996; 110:417–422.

50. Trouten, JC, Enlow, DH, Rabine, M, et al. Morphologic factors in open-bite and deep-bite. Angle Orthod. 1983; 53:192–211.

51. Tsai, H-H. Cephalometric studies of children with long and short faces. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2000; 25:23–28.

52. Turley, PK. Orthodontic management of the short face patient. Semin Orthod. 1996; 2:138–153.

53. Turvey, TA, Hall, DJ, Fish, LC, Epker, BN. Surgical orthodontic treatment planning for simultaneous mobilization of the maxilla and mandible in the correction of dentofacial deformities. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1982; 54:491.

54. Van der Dussen, FN, Egyedi, P. Premature aging of the face after orthognathic surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 1990; 18:335.

55. Van Sickels, JE, Ivey, DW. Myofacial pain dysfunction: A manifestation of the short-face syndrome. J Prosthet Dent. 1979; 42:547–550.

56. Vanarsdale, R, White, R. Three-dimensional analysis for skeletal problems. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1994; 9:159.

57. Wardrop, RW, Wolford, LM. Maxillary stability following downgraft and/or advancement procedures with stabilization using rigid fixation and porous block hydroxyapatite implants. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1989; 47:336.

58. Watted, N, Bill, JS, Witt, E. A therapeutic concept for the combined orthodontic surgical correction of Angle Class II deformities with short-face syndrome: Surgical lengthening of the lower face. Clin Orthod Res. 2000; 3:78–93.

59. Weinberg, H, Kronman, JH. Orthodontic influence upon anterior face height. Angle Orthod. 1966; 36:80–88.