Chapter 22. Shock

Shock is a clinical syndrome which is defined as ‘inadequate tissue perfusion resulting in hypoxia and ultimately in cell death’. Shock can be classified according to the mechanism by which it occurs:

Types of shock

• Hypovolaemic or haemorrhagic shock due to loss of circulating volume. Causes include: blood loss, burns and diarrhoea and vomiting

• Cardiogenic shock due to loss of normal cardiac function (‘pump failure’). Causes include: myocardial ischaemia, infarction, contusion, cardiac tamponade, massive pulmonary embolism

• Septic shock due to dilation of blood vessels by substances released in overwhelming infection. Causes include: bacterial viral or fungal infection

• Neurogenic shock due to dilation of blood vessels caused by spinal injury

• Anaphylactic shock due to dilation of blood vessels as part of a severe allergic reaction.

Hypovolaemic shock

The most common cause of shock in the prehospital environment is hypovolaemia (inadequate blood volume), usually related to blood or plasma loss from trauma, ruptured aortic aneurysm, ectopic pregnancy or gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

The priorities in the management of shock are:

• Identification of the patient at risk of significant bleeding

• Identification of shock

• Control of compressible haemorrhage

• Urgent transfer to hospital for surgical intervention.

• Tachycardia (arrhythmias may develop)

• Change in blood pressure (initially reduced pulse pressure, later lowered systolic and diastolic pressures)

• Altered mental state

• Tachypnoea

• Cool, clammy skin

• Cyanosis

• Oliguria

Compensatory mechanisms in hypovolaemic shock

• Tachycardia

• Peripheral vasoconstriction (with diversion of blood to vital organs)

• Increase in frequency and depth of respiration

• Diversion of blood within the lungs to areas of maximal gas exchange

• Increased release of oxygen from haemoglobin

• Reduced urine output.

Classification of haemorrhagic shock

Hypovolaemic shock can be divided into four grades depending on the extent of circulating volume lost.

Exact estimation of blood loss will almost never be possible and is usually overestimated. However, the following factors should be taken into consideration:

• Age (the elderly are less able to compensate for volume loss and have signs associated with a higher grade of shock but with lower blood loss)

• Fitness (athletes and fit individuals may compensate and hence have few signs or symptoms even with major losses): eventual decompensation may be very rapid

• Medications (drugs such as β-blockers, antihypertensives and antianginals may mask normal responses such as tachycardia)

• Pre-existing disease (patients with underlying conditions such as ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and pregnancy are less able to cope with the effects of shock).

A pulse of 95 bpm may be normal in an elderly patient, but can represent severe vascular compromise in a marathon runner whose resting pulse is 40 bpm.

All grades of shock will progress if the bleeding is not stopped, the only endpoint of uncontrolled bleeding is death.

Treatment principles

• The delivery of the patient to hospital must never be delayed by interventions such as intravenous access or volume replacement

• Catastrophic external haemorrhage should be addressed immediately

• The primary objective in the management of shock is to restore tissue perfusion, with the delivery of adequate oxygen and other metabolites. Only the start of this process will occur before the patient reaches hospital

• All shocked patients require the highest possible concentration of inspired oxygen delivered to the lungs

• Clearance and maintenance of a patent upper and lower airway are mandatory. This may require the patient to be intubated and positive pressure ventilation commenced

• Factors impeding ventilation, such as pneumothorax, haemothorax or gastric dilation, will require specific correction

• Identification of the patient who is at risk of injury likely to cause shock is the key first stage of the assessment of C

• Circulatory assessment includes a general assessment of the patient for:

• Coldness

• Clammy skin

• Sweating

• Mental state

• Pulse (rate and quality, presence or absence of a radial pulse)

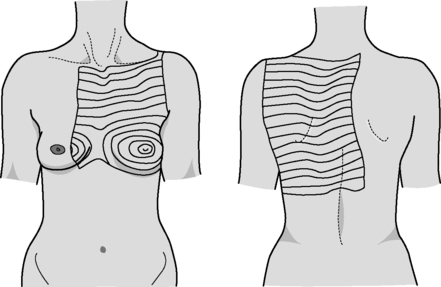

• Once external bleeding has been identified and controlled, a brief attempt should be made to identify sites of significant internal bleeding. Potential sites of bleeding are:

• Chest

• Abdomen (and retroperitoneum)

• Pelvis

• Long bones (usually from fractured femurs)

• External

• This is often referred to as ‘ blood on the floor and four more’.

Intravenous fluid therapy

• Aggressive administration of intravenous fluids is discouraged due to:

• Displacement of blood clot

• Dilution of clotting factors

• Promotion of hypothermia and secondary metabolic derangement

• Delay in reaching surgery whilst attempts to gain intravenous access are made

• If the patient is trapped or transfer times are likely to be prolonged, vascular access should be obtained.

Vascular access is often difficult because of the combination of hypovolaemia with collapsed veins and an adverse environment. If two attempts at venous access are unsuccessful then consideration should be given to the use of intraosseous access.

Once intravascular access has been achieved, crystalloid should be administered in aliquots of 250 mL to maintain the presence of a radial pulse. If the presence of a radial pulse cannot be achieved, in the circumstances of prolonged transfer or entrapment, survival is unlikely and vigorous fluid administration pending extrication and transfer to definitive care is the only option available.

Choice of fluid

• It is standard practice in the UK to start intravenous volume replacement with isotonic crystalloid solutions such as 0.9% (normal) saline or sodium lactate (Hartmann’s or Ringer lactate) solution

• Colloid solutions are significantly more expensive than crystalloids and have a small but recognised risk of anaphylactic reaction

• In the restoration of hypovolaemic shock, colloids are relatively more efficient volume for volume than crystalloid solutions. Colloid solutions may have a role in fluid therapy during prolonged transfers or in entrapment.

All fluid given should be warmed to 37°C to prevent the adverse effects of rapid infusion of cold fluid into a shocked patient.

Cardiogenic shock

Cardiogenic shock is inadequate tissue perfusion: caused by failure of the pump mechanism (the heart). It may be caused by failure of the heart muscle owing to ischaemia of the myocardium, myocardial infarction or contusion secondary to trauma. Rupture of the heart following ischaemia or penetrating trauma will also result in cardiogenic shock, exacerbated by compression of the heart caused by blood within the pericardium ( cardiac tamponade).

Massive pulmonary embolism prevents normal cardiac function and will also produce cardiogenic shock but the most common cause of cardiogenic shock is myocardial infarction producing cardiac muscle or valve rupture. This results in a mortality rate greater than 90%.

Cardiogenic shock due to tamponade may occur as a result of blunt or penetrating trauma. In blunt trauma the outlook is extremely poor however cardiac tamponade due to penetrating trauma may respond to aspiration of blood from the pericardium or thoracotomy, when the chest is opened and the hole in the heart is closed, either by the insertion of a finger, a catheter (with the balloon inflated) or a stitch.

The possibility of tamponade should be considered with any penetrating injury to the upper torso. Thoracotomy or pericardiocentesis must be performed by an experienced doctor and is best undertaken in the Emergency Department.

Other causes of cardiogenic shock require oxygen therapy, management of the underlying cause and immediate evacuation.

Causes of cardiogenic shock

Heart muscle (myocardial) dysfunction:

• Ischaemia

• Infarction

• Contusion (blunt trauma).

Cardiac tamponade:

• Trauma

• Post infarction

• Pulmonary embolism

• If the penetrating object is still in situ it must be left there and carefully protected from dislodgement or movement during a rapid transfer to hospital.

Septic shock

Septic shock results from the action of substances (mediators) released from cells as a consequence of severe infection (usually bacterial). Dilation of blood vessels, leakiness of tissue capillaries and a defect of oxygen utilisation by the tissues produce shock. The appropriate treatment for a patient with septic shock is investigation of the source of infection, intravenous antibiotics and intensive supportive care.

Septic shock usually takes some time to develop following the onset of infection. An exception is shock following suspected meningococcal infection when the patient may progress from health to death within a few hours. In this situation benzylpenicillin should be given intravenously or intramuscularly as soon as the diagnosis is made.

• All cases of septicaemic shock require oxygen and IV fluids should be started if the transfer is likely to be delayed.

Neurogenic shock

Neurogenic shock results from injury to the spinal cord, there is interruption of the nervous mechanism maintaining blood vessel wall tension; as a consequence vessels dilate, blood pressure falls and shock ensues. Neurogenic shock is therefore not associated with cold peripheries, which are instead warm and well perfused. In addition, the neurological interruption prevents a compensating tachycardia. Neurogenic shock is most commonly seen with lesions at the level of T6 and above.

The hallmarks of neurogenic shock are hypotension, warm peripheries and bradycardia.

Shock due to spinal injury is rare. Therefore shock in the trauma patient is far more likely to be due to unrecognised haemorrhage. Protect the spine, start IV fluids and transfer the patient for hospital assessment of their spinal injury.

Isolated head injury is not a cause of shock.

Clinical features of septic shock

• Low blood pressure

• Tachycardia

• Warm peripheries.

Anaphylactic shock

Anaphylactic shock results from an allergic reaction to a foreign protein such as nuts, bee stings or drugs.

The reaction is mediated by immunoglobulins and histamine and results in vasodilation and drop in blood pressure with a compensatory tachycardia.

For further information, see Ch. 22 in Emergency Care: A Textbook for Paramedics.