Chapter 16 Sexuality and Contraception

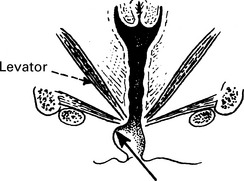

Physiology of coitus

Excitement phase

| Female | Male |

|---|---|

| Vasodilatation and vasocongestion of all erectile tissue. Breasts enlarge, the vaginal ostium opens and secretion from the vestibular glands and vaginal exudations cause ‘moistening’ | Penile erection occurs and may be transient and recur if this stage is prolonged. Scrotal skin and dartos muscle contract and draw testes towards the perineum |

Plateau phase

| Female | Male |

|---|---|

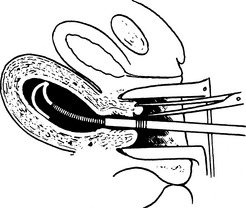

| Vasocongestion increases, and contraction of the uterine ligaments (which contain muscle) lift the uterus and move it more into alignment with the axis of the pelvis. The cervix dilates. There is engorgement of the lower third of the vagina and ballooning of the upper two thirds | The intensity of penile erection increases and the testes are enlarged by congestion. Seminal fluid arrives at the urethra as a result of sympathetic nervous stimulation of the vas deferens, seminal vesicles and the prostate. There is some pre-ejaculatory penile discharge which may contain sperm |

Orgasm

| Female | Male |

|---|---|

| Climactic sensations appear to be caused by spasmodic contractions of vaginal muscles and uterus. The female is potentially capable of repeated orgasm | Strong contractions pass along the penis causing ejaculation of seminal fluid. The greater the volume of ejaculate (after several days’ abstinence) the more intense the sensations of orgasm |

Dyspareunia

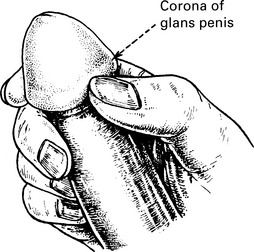

Sexual problems affecting the male

Premature ejaculation

The male ejaculates with minimal sexual stimulation or before he wishes it to occur.

Treatment options for erectile dysfunction

Papaverine

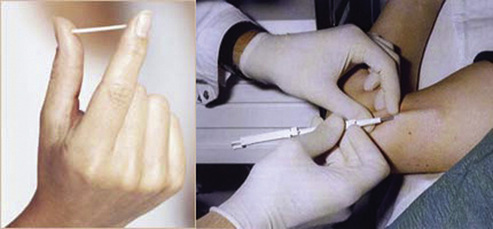

This is a smooth muscle relaxant. Intracavernosal injection is an effective treatment for impotence.

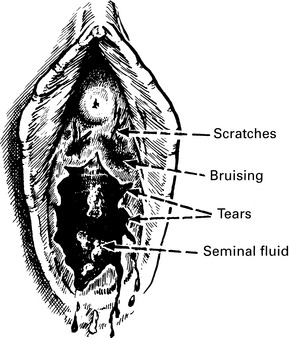

Medico-legal problems

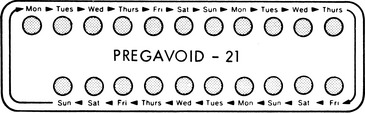

Methods of contraception

| Natural methods | Rhythm or Billings Breastfeeding (while baby is totally breast fed) | |

| Barrier methods | Diaphragm Cervical cap Condoms male and female | |

| Spermicides (usually used in conjunction with barrier methods) | Creams, films, foams, jellies, pessaries, sponges | (These are mainly Nonoxynol based) |

| Hormonal methods | Oral contraceptive Depot progestogens Vaginal | Combined oestrogen/progestogen Progestogen only Injections Subcutaneous silicone implants Silicone rings releasing oestrogen and progestogen |

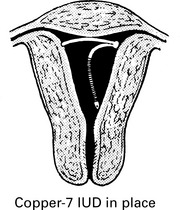

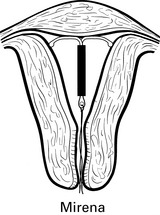

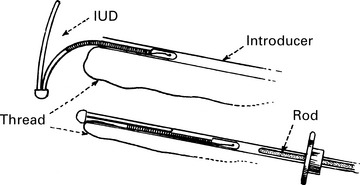

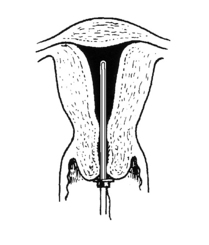

| Intrauterine devices | Inert Copper bearing Progestogen releasing (Mirena). | |

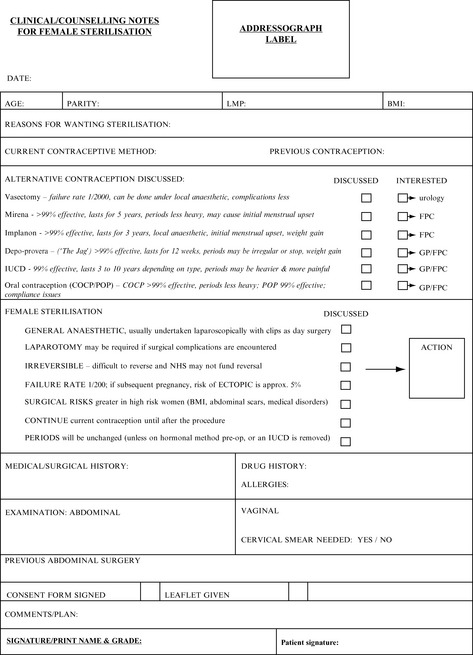

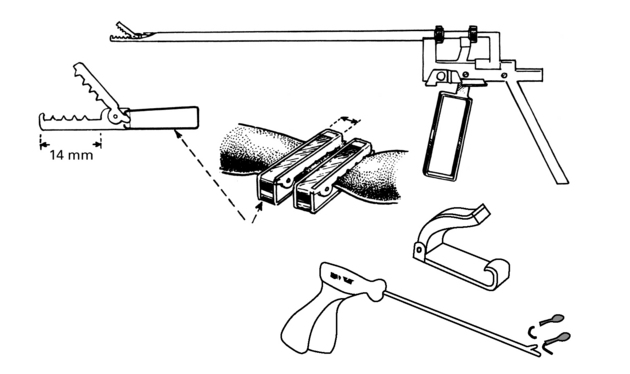

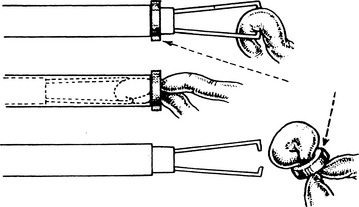

| Surgical methods | Laparoscopic sterilisation | |

| Hysteroscopic tubal occlusion (Essure) | ||

| Intrauterine quinacrine producing tubal fibrosis, in developing countries | ||

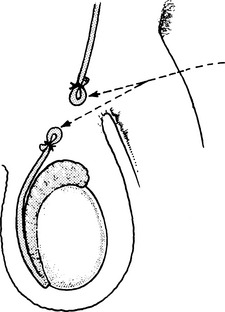

| Vasectomy |

Failure rates in contraception

There are four factors that affect the failure rate of any method of contraception:

Patient suitability for contraception

Many factors need to be taken into consideration when choosing an appropriate contraceptive method. These include age, parity, recent pregnancy, smoking, body mass index, medical history and concomitant medication. The Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare provides evidence-based guidance on its website www.fsrh.org.uk

| UKMEC categories | Definition |

|---|---|

| UKMEC 1 | A condition for which there is no restriction for the use of the contraceptive method |

| UKMEC 2 | A condition for which the advantages of using the method generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risk |

| UKMEC 3 | A condition where the theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh the advantages of using the method. The provision of a method required expert clinical judgement and/or referral to a specialist contraceptive provider since the use of this method is not generally recommended, unless other more appropriate methods are not available or are unacceptable |

| UKMEC 4 | A condition which represents an unacceptable health risk if the contraceptive method is used |

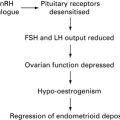

Hormonal contraception

Combined oral contraception

The pill is a mixture of oestrogen and progestogen, the combined oral contraceptive pill (COCP)

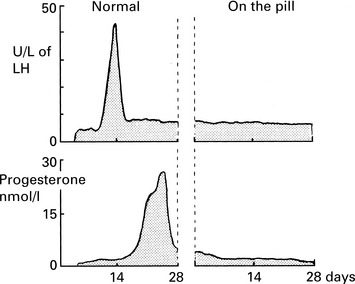

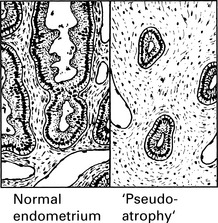

Mode of Action

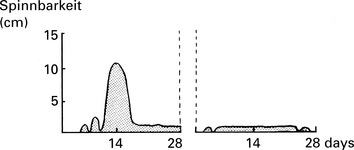

Changes in cervical mucus make sperm penetration less likely.

All these effects are the result of a synergistic action between oestrogen and progestogen.

Constituents

| Oestrogens (O) | Progestogens (P) |

| Ethinyloestradiol | Levonorgestrel |

| Norethisterone | |

| Mestranol (ethinyloestradiol-3-methyl-ether) | Ethynodiol diacetate |

| Desogestrel | |

| Gestodene | |

| Norgestimate | |

| Drospirenone |

Choice of Pill

There are over 30 brands available, using different drugs in different proportions.

| Risk of venous thromboembolic disease | |

| Non-pregnant, not on the pill | 5–10 women per 100,000 per year |

| Levonorgestrel-and norethisterone-containing pills | 15 women per 100,000 per year |

| Desogestrel and gestodene | 25 women per 100,000 per year |

| Pregnancy | 60 women per 100,000 per year |

Minor side-effects of OCs

| Oestrogen | Oestrogen and progestogen | Progestogen |

|---|---|---|

| Breakthrough bleeding | Weight gain | Acne |

| Nausea | Post-pill amenorrhoea | Depression |

| Painful breasts | Dry vagina | |

| Headache | Loss of libido |

Failure of the pill

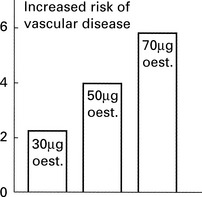

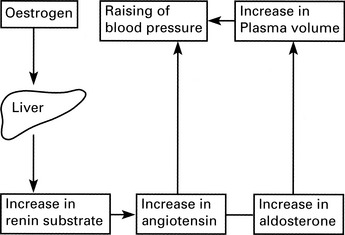

Oral contraception: risks

Conditions where COCP is contraindicated or special precaution is required:

| History of cardiovascular disease | Collagen diseases |

| Hypertension | Otosclerosis |

| Smoking | Diabetes mellitus |

| Obesity | Sickle cell anaemia |

| Chronic hepatitis | Severe varicose veins |

| Depression | Migraine |

| Acute porphyria | Arterial or venous thrombosis |

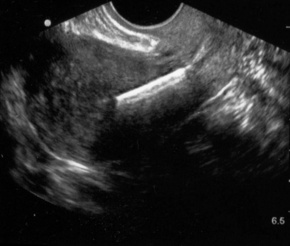

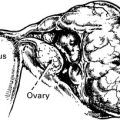

Intrauterine devices (IUDs)

Intrauterine devices (IUDs)

Complications of intrauterine devices

The chances of pregnancy are about 1–1.5 per 100 woman years and it is most likely to occur in the first 2 years. It is lower with copper-bearing coils and may be as low as 0.1 per 100 with the Mirena.† The risk of ectopic pregnancy is lower in IUD users as the risk of pregnancy is very low, but in those women who become pregnant with a coil in situ, the risk of ectopic pregnancy is higher.

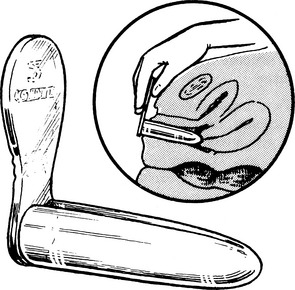

Diaphragms and caps

Caps act in a similar way but are designed to fit over the cervix.

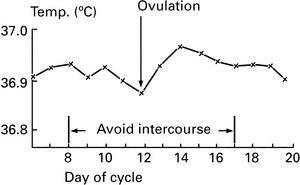

Contraception based on time of ovulation

The Ovulation Method (The Billings’ Method)

The woman is taught to identify the peri-ovulatory phase by noting the changes in cervical mucus.

| Say 5 days | Menstruation | |

| 2–3 days | ‘Early safe days’ | Sensation of vaginal dryness |

| 4–5 days | Moist days – not safe | Increasing amounts of sticky mucus |

| 2 days | Ovulation peak – not safe | Copious, clear ‘slippery’ mucus |

| 3 days | Post-ovulation Peak – not safe | Gradual decrease in secretion |

| 11 days | ‘Late safe days’ | Minimal secretion |