Chapter 31 Sexual Dysfunction and Disability

Sexual Response and Behavior

Human Sexual Response

The classic model of human sexual response was formulated by Masters and Johnson146 in the 1960s based on a study of 600 able-bodied men and women. The model depicts women and men as having similar sexual responses throughout four phases: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution (Table 31-1).148 In the Masters and Johnson model, men tend to pass through each phase faster than women and achieve only one orgasm per cycle, often with a very short plateau phase. Women can achieve multiple orgasms in the same sexual response cycle. Masters and Johnson146 also noted that women could also become “stalled” at the plateau phase and then pass straight to resolution without achieving orgasm.

| Excitement |

Modified from Masters WH, Johnson VE: Human sexual response, Boston, 1980, Bantam Books.

There have been many critics of the Masters and Johnson sexual response model, primarily because it places too much emphasis on genital responses and does not acknowledge the role of central neurophysiologic control.19,136,188,236 In the late 1970s, Kaplan devised a new model of sexual response with three phases: desire, excitement, and orgasm.119 In the Kaplan model, desire always precedes arousal, and is described as “the specific sensations that motivate the individual to initiate or become responsive to sexual stimulation.”119,125,188 The Kaplan model, like that of Masters and Johnson, proposes that human sexual response is linear and basically invariant between men and women.125

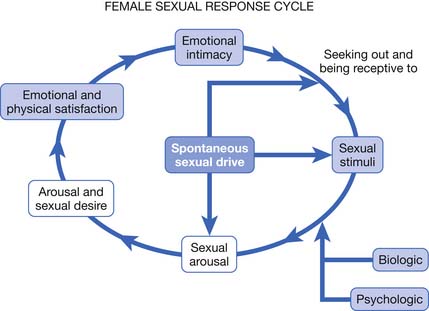

More recent research has furthered our understanding of human sexual response, particularly in regard to the ways in which the sexual response cycle is different in women and men. The Masters and Johnson, and Kaplan models ignore major components of women’s sexual satisfaction, such as the importance of trust, intimacy, affection, respect, and communication.19 Basson19–22 proposed a new model for the female sexual response to address these gender differences in 2000 to 2001 (Figure 31-1).125

FIGURE 31-1 Female sexual response cycle.

(Redrawn from Kingsberg SA, Janata JW. Female sexual disorders: assessment, diagnosis, and treatment, Urol Clin North Am 34:497-506, 2007.)

Basson’s circular model emphasizes that sexual response in women is much more complex than in men. In women a sexual encounter does not necessarily start from a place of spontaneous sexual drive or desire. Women often approach becoming intimate from a point of sexual neutrality, and the decision to become sexually engaged can result from numerous and varied factors, including a wish to emotionally connect with their partner.19,125 Sexual arousal and sexual satisfaction often do not occur solely through physical means such as clitoral stimulation and orgasm, but can also be dependent on intangible factors such as the ability to focus the mind on the present moment and a feeling of security or psychologic well-being.25 The circular sexual response cycle might be repeated many times within the same sexual encounter.25 Janssen et al.112 have also proposed a circular model of human sexual response that is similar to that of Basson, but that might be more applicable to both genders.

Sexual Behavior and Aging

The frequency of sexual activity has been well documented to decline with age.116 Recent research has shown that the degree of decline is much less than was previously thought and that sexuality remains an important contributor to quality of life throughout the entire lifespan.44,116 An important reason for the discrepancy is that older studies tended to quantify sexual activity only as intercourse, but more modern research looks at all aspects of sexuality.116 One study of men and women aged 80 to 102 years found that 63% of men and 30% of women continued to engage in sexual intercourse, whereas 83% of men and 64% of women participated in touching and caressing activities without intercourse, and 72% of men and 40% of women engaged in masturbation.44

Many medical factors influence sexual activity in the elderly, including sexual dysfunction caused by medical illness, increasing frailty, and the side effects of medications. Postmenopausal women tend to experience vulvovaginal atrophy and vaginal dryness, which causes pain with vaginal penetration.118 Men have decreased testosterone with advancing age, which contributes to diminished sexual drive and also has physical effects that contribute to increased frailty.117 Psychosocial barriers to sexual activity in the elderly are numerous, including decreased partner availability, alterations in body image and change in self-perception, cognitive decline, and environmental issues such as the loss of privacy experienced in many residential settings.79,117

Types of Sexual Dysfunction

Classification Systems

Sexual dysfunction is most frequently classified according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR).10 To qualify as a sexual dysfunction, a person’s sexual problem must cause “marked distress or interpersonal difficulty.” This distinction is important to remember for patients with disabilities, because they might experience altered sexual response but not have a sexual dysfunction in need of further workup or treatment.219 In the same way that spasticity after stroke or phantom sensations after amputation are not always problems that need to be addressed by the physician, a patient’s sexual difficulties only need to be treated when the patient’s quality of life is adversely affected.

The DSM-IV-TR allows for three subtypes to be applied to all primary diagnoses to further clarify the nature of the sexual dysfunction. The first subtype describes the onset of the disorder—lifelong or acquired (which means it developed after a period of normal functioning). The second subtype is used to designate the context in which the dysfunction occurs—generalized or situational (meaning limited to certain types of stimulation, situations, or partners). The third subtype delineates the etiologic factors associated with the sexual dysfunction—the practitioner must decide whether the problem is due to psychologic factors alone, or due to a combination of psychologic factors and the pathologic effects of a general medical condition. If the sexual disorder is fully explained by a general medical condition or substance abuse, without psychogenic factors, then it is coded separately. The DSM-IV-TR sexual dysfunctions are summarized in Table 31-2.10 There has been recent scholarly debate about the clinical usefulness of the DSM-IV-TR system of classification.13,27,28 It is based on the Masters and Johnson, and Kaplan linear models of human sexual response, and therefore often criticized as not being representative of the true nature of human sexual response, particularly for female sexual dysfunction.19 Another problem with the DSM-IV-TR criteria is that sexual disorders, particularly erectile dysfunction and dyspareunia, are typically diagnosed independent of etiology. Sexual disorders are difficult to fully classify according to criteria which mandate that the etiology is known before diagnosis.27 In addition, research has shown that there is often a high degree of overlap or comorbidity among the sexual disorders, particularly in women, and the DSM-IV-TR classification system does not allow for these findings.27,135,190,206

| Sexual Desire Disorders | |

| 302.71 | Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder |

| 302.79 | Sexual Aversion Disorder |

| Sexual Arousal Disorders | |

| 302.72 | Female Sexual Arousal Disorder |

| 302.72 | Male Erectile Disorder |

| Orgasmic Disorders | |

| 302.73 | Female Orgasmic Disorder |

| 302.74 | Male Orgasmic Disorder |

| 302.75 | Premature Ejaculation |

| Sexual Pain Disorders | |

| 302.76 | Dyspareunia (not due to a general medical condition) |

| 306.51 | Vaginismus (not due to a general medical condition |

| Sexual Dysfunction Due to a General Medical Condition | |

| 625.8 | Female Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder due to a general medical condition |

| 608.89 | Male Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder due to a general medical condition |

| 607.84 | Male Erectile Disorder due to a general medical condition |

| 625.0 | Female Dyspareunia due to a general medical condition |

| 608.89 | Male Dyspareunia due to a general medical condition |

| 625.8 | Other Female Sexual Dysfunction due to a general medical condition |

| 608.89 | Other Male Sexual Dysfunction due to a general medical condition |

| ___.__ | Substance-Induced Sexual Dysfunction (coding is substance-specific) |

| 302.70 | Sexual Dysfunction Not Otherwise Specified |

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR), Washington, DC 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

A number of international consensus conferences have been held to address these concerns.26,27,140,141 Their guidelines follow the same general format as the DSV-IV-TR (primarily to retain consistency for research purposes), but they introduced updated definitions of the disorders. The DSM-V is set to be published in 2012, but until that time the reports of these consensus conferences contain the current best set of definitions of sexual dysfunction, and are summarized and expanded on below.11

Male Sexual Dysfunction

The main focus of both clinical care and research for men with sexual dysfunction has traditionally been centered on performance problems, particularly erectile dysfunction and premature ejaculation. There has been a major paradigm shift in the past two decades away from the psychiatric understanding of most sexual disorders in men and toward a medicalization of male sexuality (particularly with the advent of proerection medications).150,156,192 Purely psychogenic male sexual disorders are much more underrepresented in the medical literature and are often misdiagnosed as erectile dysfunction by health practitioners.157 Types of male sexual dysfunction include the following:

Female Sexual Dysfunction

Female sexual dysfunction is very common, with a reported prevalence of 40% to 50% in multiple population-based studies.13,135 Sexual dysfunction in women has become a focus of renewed research interest in the past decade, in part based on the new understanding of the female sexual response cycle proposed by Basson,19 and the implications of that understanding toward diagnosis and treatment.150 In contrast to sexual dysfunction in men, the psychologic aspect of women’s sexual functioning typically receives far more attention than organic etiologies of dysfunction. This discrepancy is partially because of institutional bias, but it is also based on a growing body of data suggesting that psychologic factors correlate more strongly with sexual dysfunction in women than do medical problems.26,135 It is especially important to remember that personal distress is necessary to make a diagnosis of sexual dysfunction when dealing with female patients. Up to 50% of women who report a problem with sexual functioning do not have any associated personal distress, and so they cannot be classified as having a sexual dysfunction.207 Types of female sexual dysfunction include the following:

Sexual Dysfunction in Disability and Chronic Disease

Spinal Cord Injury

In contrast to many of the other disabilities discussed in this chapter, sexual dysfunction in patients with spinal cord injury (SCI) has been well studied in both genders (see Chapter 55). The type of sexual dysfunction the patient will ultimately experience depends in large part on the spinal cord level and the degree of completeness of the injury.162 Multiple studies have shown that the frequency of sexual activity and the level of sexual satisfaction decrease in both men and women after sustaining an SCI.5,53,221

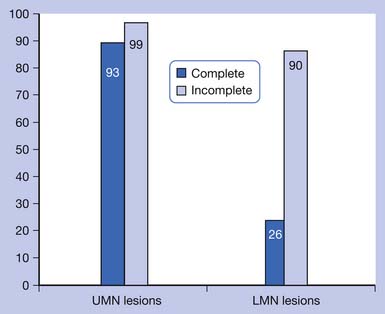

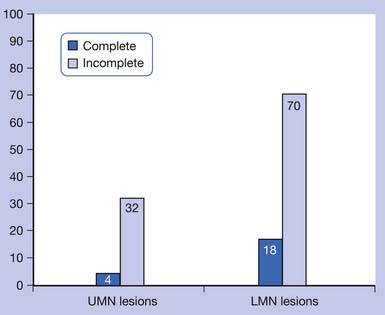

Bors and Comarr41 conducted a pivotal study in 1960 detailing the prevalence of erectile and orgasmic dysfunction in 529 men with SCI. They found that in men with complete UMN lesions, 93% of patients were able to achieve reflexogenic erections, and none were able to attain psychogenic erections. Anterograde ejaculation in complete UMN SCI was seen in 4% of patients. Men with incomplete UMN SCI achieved erections 99% of the time, with 80% of men having only reflexogenic erections and 19% having combined reflex and psychogenic erections. Ejaculation was possible in 32% of patients with incomplete UMN SCI, with 72% of those occurring after reflexogenic erection and 26% occurring after psychogenic erection. Complete LMN lesions showed a very different picture, with 26% of patients able to achieve psychogenic erections and none attaining reflexogenic ones. Ejaculation was possible in 18% of these men. Incomplete LMN lesions fared far better, with 90% of men retaining the ability to achieve erection and 70% the ability to ejaculate. The results of the Bors and Comarr study are summarized in Figures 31-2 and 31-3.

FIGURE 31-2 Percentage of men with spinal cord injury able to achieve erection.

(Data from Bors E, Comarr AE: Neurological disturbances of sexual function with special reference to 529 patients with spinal cord injury, Urol Surv 110:191-221, 1960.)

FIGURE 31-3 Percentage of men with spinal cord injury able to achieve anterograde ejaculation.

(Data from Bors E, Comarr AE: Neurological disturbances of sexual function with special reference to 529 patients with spinal cord injury, Urol Surv 110:191-221, 1960.)

Orgasmic ability has been shown to be preserved in 38% to 50% of men with complete UMN SCI, 78% to 84% of men with incomplete UMN injury, and 0% of men with complete LMN injury.5,6,178,218 It should be noted, however, that most studies of men have focused on the ability to ejaculate instead of the ability to have an orgasm, which have more recently been noted to be separate occurrences.6 Some men are also occasionally able to achieve orgasm without anterograde ejaculation, possibly indicating either anejaculation or retrograde ejaculation into the bladder.218

Women with SCI have more recently been shown to have sexual responses that are similar to those of men, with arousal and vaginal lubrication as the female correlate to penile erection.222,223 In women with complete UMN injuries, reflexogenic but not psychogenic lubrication is preserved.223 Sensation to light touch and pinprick in the T11–L2 dermatomes was found to be predictive of the ability for psychogenic vaginal lubrication (which is thought to be sympathetically mediated).222 From 44% to 54% of women with SCI have been shown to be able to achieve orgasm, although orgasm is much less likely in women with LMN injuries affecting the S3–S5 segments.53,110,221,222

Fertility in men with SCI is impaired, in part because of a decreased ability to ejaculate.181 Semen quality has also been found to be poor in men with SCI, with decreased sperm motility, decreased mitochondrial activity, and increased sperm DNA fragmentation.183 Reasons for altered semen quality have been postulated to include seminal fluid stasis, testicular hyperthermia, recurrent genitourinary tract infections, and hormonal dysfunction.183 Fertility in women with SCI is preserved once menstruation resumes, on average about 5 months postinjury.15

Stroke

Stroke is the world’s second leading cause of death and the leading cause of adult disability.54 Sexual dysfunction is a common finding after stroke in both men and women (see Chapter 50). The most common findings for men are erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction (in 40% to 50%) and decreased sexual drive.115,127,145,233 Women tend to experience decreased sexual drive, decreased vaginal lubrication (in approximately 50%), decreased orgasm (in about 20% to 30%), and decreased overall sexual satisfaction.123,127,145,233 The prevalence of decreased sexual drive has been reported to be between about 25% and 60% in both genders after stroke.123,127 Stroke also leads to significantly decreased frequency of sexual activity in both genders, and in one study, approximately 50% of stroke survivors reported no sexual activity whatsoever by 1 year poststroke.86,127,233

The physical effects of stroke that contribute to sexual dysfunction include hemiparesis with its effect on body positioning and movement, hemineglect, hemianopsia, neurogenic bowel and bladder, and spasticity.163,181 Not much is known about the functional neuroanatomy of sexual behavior and control, but some studies have indicated that the right cerebral hemisphere might play a more important role in sexual functioning than the left side.57,83,115 Many studies have suggested that sexual dysfunction after stroke is related to the presence of medical comorbidities (cardiac disease, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, depression), medications, and psychosocial factors (inability to discuss sexuality with the partner, unwillingness for sexual activity, fear of another stroke, sexuality being unimportant) rather than the direct effect of stroke.∗

Traumatic Brain Injury

The prevalence of sexual dysfunction after traumatic brain injury has been reported at 4% to 71%, a wide range that likely represents the limited number of quality studies and the varied types and severities of injury that are possible201 (see Chapter 49). Types of sexual dysfunction reported have been similar to those seen in patients with stroke, including reduced sexual desire and frequency of sexual activity in both genders, ED and ejaculatory dysfunction in men, and dyspareunia, anorgasmia, and reduced lubrication in women.104,128,181,201 In addition, brain injury can cause hypersexual behavior such as excessive masturbation. This can occur in particular with injury to the limbic system or prefrontal regions, which can cause disinhibition; or to bilateral temporal poles, which produces the Klüver-Bucy syndrome of hypersexuality and hyperorality.46,137,217 The prevalence and type of sexual dysfunction can be associated with both the global amount of brain tissue destroyed and the focality of injuries.181 Sexual dysfunction does not seem to correlate with the amount of cognitive impairment, the length of posttraumatic amnesia, or the burden of neurologic disability.40,181,201 Medications, particularly anticonvulsants, can greatly contribute to the sexual dysfunction witnessed after brain injury.89 Psychosocial factors seems to play a major role in sexual functioning after brain injury, with the presence of depression being the most sensitive indicator for sexual dysfunction.104 Other important psychologic factors include perceived health status and quality of life, low self-esteem, anxiety, and perceived decline in personal sex appeal.104,129

Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS)-induced sexual dysfunction is present in 40% to 80% of women and 50% to 90% of men66 (see Chapter 52). Women tend to have decreased sexual desire, anorgasmia, decreased vaginal lubrication, and increased spasticity with sexual activity.61,107,181 Many of these symptoms are thought to be related to the decreased genital sensitivity experienced by 62% of women with advanced MS.107 Men with MS have ED, ejaculatory dysfunction (premature, delayed, or absent), orgasmic dysfunction, decreased genital sensation, and decreased sexual drive.61,181

The sexual disorders have historically been attributed directly to the location and duration of the spinal cord or brain lesion, but more recent research tends to describe a multitude of other factors that also contribute to the development of sexual dysfunction in MS. These include secondary physical limitations, psychologic factors, and the side effects of MS medications.134,227 In one study, sexual dysfunction in men with MS was found to be positively correlated with lower-limb disability and bladder dysfunction, but in women the sexual disorders were most strongly correlated with fatigue.80 Secondary physical limitations include fatigue, bowel and bladder dysfunction, muscle weakness, spasticity, poor coordination, inability to properly position oneself for an enjoyable sexual encounter, numbness, paresthesias, pain, and cognitive impairment.134,227 Psychosocial factors that significantly contribute to MS-related sexual dysfunction include poor self-image, poor self-esteem, fear of isolation and abandonment, shame, dependency on one’s partner to provide for one’s basic needs, and depression.204,227

Other Neurologic Disorders

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is often associated with low testosterone levels, and therefore decreased sexual drive163 (see Chapter 51). In one study of young men with PD (ages 36 to 56 years), up to 40% had low sexual desire. Men with PD also can experience ED and PE.181 Treatment with dopamine and dopamine agonist medications, on the other hand, has been documented to cause hypersexual behavior, which often accompanies mania.238 Hypersexuality has also been described with deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus.185

Patients with epilepsy can exhibit involuntary sexual gestures, erotic feelings, and orgasm during seizure activity.181 These dysfunctions are most commonly seen with complex partial seizures arising from the temporolimbic or frontolimbic circuitry.181 Ictal genital automatisms (such as self-fondling or pelvic thrusting) were reported in one study to occur in 11% of patients observed with video electroencephalographic monitoring.69 Ictal orgasm has been reported much more frequently in women than in men.181

Peripheral neuropathy can cause sexual dysfunction, particularly when the etiology is diabetes, amyloid, and some of the inherited neuropathies with urogenital symptoms as prominent early features.181 Guillain-Barré syndrome has been linked to ED when there is residual neurologic deficit or disability after recovery.50

Chronic Pain

The reasons for sexual dysfunction in patients with chronic pain are multifactorial, often related to physiologic, pharmacologic, and psychologic factors173 (see Chapter 42). In one study, 73% of patients with chronic pain had pain-related difficulty with sexual activity. The reasons for this included decreased arousal, positioning issues, exacerbations of pain, low confidence, performance worries, and relationship issues.9 In another study, sexual problems were reported in 46% of patients with low back pain.71 Women with low back pain have been shown to have decreased frequency of sexual activity, more pain during sexual intercourse, and decreased sexual desire compared with men with low back pain or patients of either gender with neck pain.143 Sexual dysfunction in patients with chronic pain has been correlated most strongly with the presence of depression, poor coping skills, and shorter pain duration.130 Many of the medications used to treat chronic pain (including opioids, antidepressants, and anticonvulsants) can independently contribute to sexual dysfunction.235 Chronic pelvic pain in women, which frequently causes dyspareunia and other sexual dysfunctions, can be related to childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, and emotional neglect. It can also have an organic etiology (as detailed previously in this chapter).133

Rheumatologic Disease

Osteoarthritis affects sexual function primarily through associated joint pain, stiffness, and fatigue, and the hip joint is the most often implicated in leading to sexual difficulties38,60,163 (see Chapter 36). Total hip replacement often significantly improves sexual functioning; in one study, 65% of patients found relief from sexual difficulties after the surgery.231 It is important to instruct patients in proper positioning after joint replacement to reduce the risk of dislocation, and many surgeons instruct patients to refrain from sexual intercourse for 1 to 2 months after hip replacement for this reason.220

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA), like osteoarthritis, can cause problems in sexual functioning through joint pain, stiffness, and fatigue.166 RA in men has also been shown to be associated with decreased sexual desire and ED during periods of active inflammation.93 One recent study of women with RA identified 62% with difficulties in sexual performance caused by joint pain and stiffness, and 92% with diminished sexual desire or satisfaction.2 Difficulties in sexual performance were related to the overall level of disability and hip involvement, whereas decreased sexual desire and satisfaction were correlated more with perceived pain, age, and depression.

The effect of fibromyalgia on sexual dysfunction in women has been looked at in one recent study,172 which found that 97% of women with fibromyalgia reported sexual dysfunction, including decreased sexual desire, arousal, and orgasm. The degree of sexual difficulty was found to be very strongly correlated with the degree of depression. Other correlates included level of anxiety, age, pain intensity, and marital and work status.

Amputation

Patients with limb amputation usually have preserved sexual genital functioning (unless there is a comorbid condition such as diabetes or cardiac disease, or the side effects of their medications play a significant detrimental role)108 (see Chapters 12 and 13). But their sexual life can be significantly affected by a variety of factors associated with their amputation, including depression, poor self-esteem and body image, phantom sensations and pain, problems with balance and movement, and difficulties with body positioning during sexual activity.212 Preservation of the knee joint can be helpful for maintaining balance during sexual intercourse, although transfemoral amputees can use pillows to aid in positioning.48 Upper limb amputees would benefit from side-lying or supine positioning to allow for free movement of both the intact arm and the residual limb.220

Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the major comorbidities affecting people with disabilities, because its presence is a significant risk factor for subsequent stroke and amputation. DM plays a clear role in the development of sexual dysfunction in men. ED is three times more common in men with DM than in the general population, with prevalence estimates ranging from 35% to 75%.30,144,227 PE has also been documented in 40% and hypoactive sexual desire in 25% of men with diabetes.144 Diabetes-related sexual dysfunction in men is strongly correlated with glycemic control, duration of disease, and burden of diabetic complications.30 The pathogenesis of sexual dysfunction in DM is likely multifactorial, including vasculopathy, autonomic neuropathy, and diminished nitric oxide production, which leads to decreased neurogenic vasodilation.13,227

Diabetes in women has a much less clear effect on sexual functioning, as research is limited and at times contradictory.163 The most commonly reported condition is sexual arousal disorder, with its accompanying decreased vaginal lubrication.13 Low sexual desire, decreased clitoral sensation, orgasmic dysfunction, and dyspareunia have also been infrequently reported.51 Factors for the development of sexual dysfunction in women with diabetes have been analyzed, and a far different picture has emerged than for men with diabetes. There has been no documented correlation to body mass index, presence of diabetic complications, length of disability, or level of glycemic control.13,72,73 Associations have been shown for cardiovascular comorbidity, depression, and age.240

Cardiac Disease

Cardiovascular disease is another common comorbidity in patients with disabilities (see Chapter 33). Hypertension, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure have all been associated with an increased prevalence of sexual dysfunction.34,39,227 Hypertension is the most prevalent comorbidity among men with ED.49,227 ED has been noted in 40% to 95% of hypertensive men and is correlated with duration of hypertensive disease.75,159 Control of blood pressure often leads to restoration of erectile function.163 ED is also common in cardiac disease, with a prevalence of 42% to 75%.180 ED is often one of the earliest indicators of cardiovascular disease, and men (with or without disabilities) who have ED with no obvious cause should be worked up for this potentially deadly comorbidity.227 It has been reported that 25% to 63% of women with cardiac disease experience sexual dysfunction, including decreased sexual desire, vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, decreased genital sensation, and decreased orgasmic ability.3,34,227

Cardiac disease, especially after myocardial infarction has been sustained, is often associated with depression and anxiety, which can contribute to sexual dysfunction.82,92,186 Other psychologic factors that likely play a role include a fear of recurrence of cardiac symptoms or a fear of death with resumption of sexual activity.103 Cardiovascular deaths during sexual intercourse are actually very rare, with the rate in men estimated to be 0.2 per 100,000 and the risk in women 12 times lower than in men.177

Many cardiovascular medications (including antihypertensives and digoxin) have been known to contribute to the sexual dysfunction seen in cardiac disease.235

Depression

Depression is one of the most common comorbidities in patients with all types of disabilities, and it has been shown to contribute to sexual dysfunction in a variety of ways, including medical, pharmacologic, and psychosocial57 There has been intense research and publicity about the sexual side effects of antidepressant medications, but untreated depression has also been strongly correlated with sexual dysfunction.210 In one study of 134 patients with major depressive disorder who were not taking any medication to treat their illness, hypoactive sexual desire was seen in 40% to 50% of men and women, decreased arousal was observed in 40% of women, ED was seen in 50% of depressed men, and ejaculatory or orgasm difficulties were seen in 15% to 20% of men and women.121 Psychosocial factors in depressed patients that likely play a role in the development of sexual dysfunction include interpersonal relationship difficulties and poor body image and self-esteem.56

Sexual Dysfunction and Medications

Sexual dysfunction is a common side effect of many medications used routinely in patients with disabilities. It is important for the practitioner to maintain open communication with patients, understand these sexual side effects, and explain the risks to patients before prescribing these drugs. If sexual dysfunction occurs secondary to the use of a medication, it is often necessary to switch to a different class of medications to regain the function that has been lost or altered. Another alternative, especially in men, is to use a medication such as a phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitor to counteract the sexual side effects of the initial medication. Table 31-3 presents an overview of the sexual dysfunctions associated with various classes of medications commonly encountered in a physiatry practice. It should be noted that a majority of the research in this area has been focused on male sexual dysfunction, so less is known about the effects of these medications on sexuality in women.

| Drug Class | Impact on Sexual Function |

|---|---|

| Diuretics (thiazides, spironolactone, loop diuretics, chlorthalidone) | Erectile dysfunction, decreased sexual desire, impaired ejaculation, retrograde ejaculation |

| Centrally acting sympatholytics (clonidine, α-methyldopa) | Erectile dysfunction, decreased sexual desire |

| β-Blockers | Erectile dysfunction, decreased sexual desire (men and women) |

| α-Blockers (prazosin, terazosin) | Erectile dysfunction, priapism (rare), retrograde ejaculation |

| Vasodilators (hydralazine) | Priapism (rare) |

| Antiarrhythmics (digoxin, disopyramide) | Erectile dysfunction, decreased sexual desire |

| Anticholesterolemics | Erectile dysfunction, decreased sexual desire |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | Ejaculatory dysfunction, anorgasmia (men and women), decreased sexual desire (men and women), erectile dysfunction |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Decreased sexual desire, erectile dysfunction |

| Trazodone | Priapism |

| Antipsychotics | Decreased sexual drive (men and women), ejaculatory dysfunction, erectile dysfunction, priapism |

| H2-Blockers (especially cimetidine) | Erectile dysfunction, decreased sexual desire, painful erections, gynecomastia |

| Baclofen | Ejaculatory and erectile dysfunction, decreased orgasmic function (men and women) |

| Gabapentin | Ejaculatory dysfunction, anorgasmia (men and women), and decreased sexual desire (men and women) |

| Opioids | Decreased sexual desire, anorgasmia, erectile dysfunction |

| Benzodiazepines | Orgasmic dysfunction (women), delayed ejaculation, decreased sexual desire |

| Neurostimulants (methylphenidate, amantadine) | Hypersexual behavior |

Antihypertensive and Cardiovascular Medications

Sexual side effects are one of the main reasons for noncompliance with antihypertensive drugs.43 Diuretics have been linked to ED, impaired ejaculation, and diminished sexual desire, particularly with spironolactone, thiazides, chlorthalidone, and loop diuretics. The frequency of reported sexual dysfunction with diuretics averages about 5%.235 Thiazides can also cause retrograde ejaculation. Sympatholytic agents have also been implicated, particularly with centrally acting medications such as α-methyldopa and clonidine, which cause ED or decreased sexual drive in up to 20% to 30% of patients.158,235 β-Blockers produce sexual dysfunction (primarily ED in men and decreased sexual desire in both men and women) through their effect on the sympatholytic and vascular system. This effect is worse with nonselective agents and is thought to be dose related.77,158,235 These medications caused significant sexual dysfunction in the past when complete β-blockade was achieved through very high doses of these medications, but recent studies have shown that the sexual side effects of these medications at modern dosages are much more limited and comparable to those of other antihypertensive classes.31,111,126,230 α-Blockers such as prazosin and terazosin have been implicated in ED, retrograde ejaculation, and priapism in a few case reports.29,235 There have been no significant reports of sexual dysfunction with calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blockers. Hydralazine, which is a vasodilator, has been linked to rare cases of priapism.235

Digoxin has been shown to cause decreased desire and ED in up to 36% of patients.165 It is has a chemical structure similar to that of the sex hormones and has been associated with decreased testosterone and luteinizing hormone levels, increased estrogen levels, and gynecomastia.82,235 The antiarrythmic drug disopyramide has been associated with ED.7,152

Several medications used to treat hypercholesterolemia have been implicated in ED and decreased sexual drive. These include statins, fibrates, and niacin.158,184 The mechanism for this effect is unclear, but these drugs likely affect the substrates for sex hormones. 235

Antidepressant Medications

Many different classes of antidepressant medications can cause sexual dysfunction. It can be difficult to distinguish whether a patient’s sexual dysfunction is secondary to the depression itself or to the antidepressant medication.17

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) tend to cause ejaculatory dysfunction in men (delayed or absent ejaculation and orgasm) and delayed or absent orgasm in women.29,209 Low sexual desire is another significant sexual dysfunction reported in patients of both genders taking SSRIs.29 SSRIs can also cause ED, but it is usually to a much lesser extent than ejaculatory dysfunction.235,239 Prevalence estimates for sexual dysfunction in patients taking SSRIs range from 16% to 73%, with a higher prevalence in men than in women.12,209 There does not appear to be significant differences among individual drugs of this class, as the rate of ejaculatory dysfunction has been reported to be 20% to 75% for fluoxetine, 20% to 67% for sertraline, and 20% to 30% for paroxetine.208

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), used for the treatment of depression and neuropathic pain, can cause ED as well as low desire.158 The effect is mediated through anticholinergic mechanisms.235 Of all the TCAs, desipramine seems to have the lowest incidence of sexual side effects.208 Trazodone, which has a heterocyclic structure similar to TCAs, has been associated with priapism.235 Heterocyclic monoamine oxidase inhibitors have been associated with the highest incidence of sexual dysfunction of all the antidepressants.235 Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors also can cause sexual dysfunction, particularly ED and low desire, although venlafaxine has significantly more sexual side effects than duloxetine.242 Lithium has been shown to cause sexual dysfunction in 14% of patients when administered alone, but in 49% of patients who were also given benzodiazepines.84 Bupropion and mirtazapine seem to have the least effect on sexual functioning of all the antidepressants.56,160

Antipsychotic Medications

Neuroleptic drugs have been reported to cause significant sexual dysfunction because of the increased prolactin levels caused by dopamine antagonism.235 Both conventional and atypical antipsychotic medications have been implicated, and the most common side effect is decreased sexual desire, which occurs in 20% to 73% of patients.14,142 Ejaculatory dysfunction, ED, and priapism have been reported with most of the antipsychotic drugs, including haloperidol, risperidone, chlorpromazine, and thioridazine.29,45,232,235 Retrograde ejaculation in men and delayed or absent orgasm in women are also concerns with these medications.29 For the atypical antipsychotics, the risk of sexual dysfunction has been reported to be between 18% and 96%, and risperidone seems to be associated with the most sexual dysfunction and quetiapine the least.97

Gastrointestinal Medications

The histamine-2 (H2) blocker cimetidine has been reported to cause ED, painful erections, low sexual desire, gynecomastia, and decreased sperm count.168,235,243 The mechanism is thought to be through its antiandrogen effect.235 Other H2-blockers such as ranitidine and famotidine have also been implicated in ED, but to a lesser extent.235 The proton pump inhibitor omeprazole can cause gynecomastia and ED, but the mechanism is unknown.52,138 Metoclopramide can lead to decreased sexual drive and ED in men, with a presumed mechanism of inducement of hyperprolactinemia.235

Other Medications Used in Physiatry Practice

Baclofen, particularly with intrathecal administration, has been shown to be associated with erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction.67,113,203 There have been case reports of oral baclofen administration associated with decreased orgasmic function in men and women, which could be related to its negative effect on pelvic floor contraction, given that it acts as a true muscle relaxant.151

Anticonvulsant medications induce the cytochrome P450 pathway, which increases the metabolism of androgens and can lead to sexual dysfunction.235 Primidone, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, and phenytoin have all been associated with ED and decreased sexual drive.29,158,235 Gabapentin, an anticonvulsant used more frequently for the treatment of neuropathic pain, has been reported to cause decreased sexual desire and anorgasmia in men and women, and ejaculatory dysfunction in men.62,94,132 Pregabalin was linked to ED in a case series of five patients.105

Opioids decrease sexual drive and cause anorgasmia in men and women, and can also cause ED and decreased sexual desire and subjective arousal.29,235 The mechanism is thought to be related to a decrease in testosterone levels and hypogonadism seen with long-term opiate administration.63,235 These effects have also been seen with intrathecal opioid administration, and in men receiving methadone and buprenorphine maintenance treatment for drug addiction.47,98,174 Tramadol has been associated with delayed ejaculation and anejaculation.200 Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs have been linked to ED.215

Benzodiazepines, including alprazolam, diazepam, and clonazepam, have been noted to cause delayed orgasm and anorgasmia in women and delayed ejaculation in men.12,170,202 They have also been associated with decreased sexual desire and arousal.237

The neurostimulants methylphenidate and amantadine have both been reported to cause hypersexual behavior.35,76,229

Corticosteroids have been reported to cause low sexual desire.158 Methotrexate has been implicated in ED, decreased sexual drive, and gynecomastia.4

Evaluation of Sexual Dysfunction

Sexual History Taking

The idea of obtaining a sexual history can be a daunting one to some practitioners. The most important thing to remember is that patients’ quality of life can be significantly improved if their physician is unafraid to discuss this topic with them. Because sexuality is a sensitive topic, it is best to maintain an attitude of openness and flexibility throughout the interview. The “ALLOW,” “PLISSIT,” and “BETTER” models are three different approaches for facilitating such a conversation (Box 31-1).79,100,106

BOX 31-1 ALLOW, PLISSIT, and BETTER Models for Facilitating Communication About Sexuality

Data from Frank JE, Mistretta P, Will J: Diagnosis and treatment of female sexual dysfunction, Am Fam Physician 77:635-645, 2008; Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzichristou DG, et al: Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study, J Urol 151:54-61, 1994 and Hordern A. Intimacy and sexuality after cancer: a critical review of the literature, Cancer Nurs 31:E9-E17, 2008.

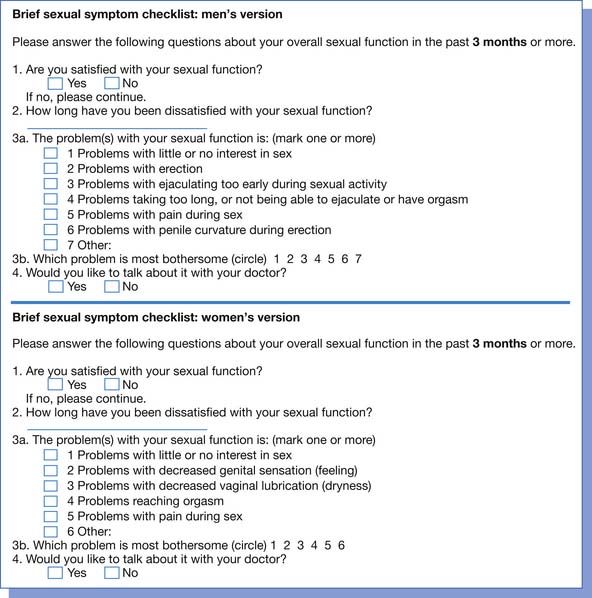

When asking a patient about sexual dysfunction, it is important to assess the nature of the problem and the time course of the complaint (including whether it started in relation to a certain disability, medical comorbidity, or medication administration). It is equally vital to learn whether the patient is experiencing dissatisfaction or disruption of quality of life as a result of the sexual dysfunction. The Brief Sexual Symptom Checklist is a self-report tool that can be a useful adjunct to the practitioner’s comprehensive sexual history (Figure 31-4).100

FIGURE 31-4 The Brief Sexual Symptom Checklist for men and women.

(Redrawn from Hatzichristou D, Rosen RC, Broderick G, et al. Clinical evaluation and management strategy for sexual dysfunction in men and women, J Sex Med 1:49-57, 2004.)

A thorough inquiry into the patient’s sexual dysfunction also includes obtaining information about the medical, sexual, and psychosocial history of the patient.100,118 The basic medical history includes both medical and surgical history, medication use (including over-the-counter and herbal medications), substance use (smoking, alcohol abuse, and recreational drug use), and family medical history.80 Important medical conditions to inquire about include cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, cancer, benign prostatic hyperplasia or the presence of lower urinary tract symptoms, neurologic diseases (SCI, MS, traumatic brain injury, stroke), thyroid conditions, and endocrine deficiencies (such as hypogonadism, androgen insufficiency, or estrogen deficiency).31,100,124,205 In women, it is also necessary to ask about reproductive history, history of gynecologic diseases such as fibroids or endometriosis, and current menstrual status.124

The basic sexual history includes age of first sexual experience, types of sexual practices, gender of partners, history of sexually transmitted diseases, inquiry into safe sex practices, and type of birth control used.18 It should never be assumed that the patient is heterosexual, and gender-neutral terms (such as “partner” instead of “boyfriend” or “wife”) are preferable until the issue has been clarified by the patient.18,118

The psychosocial history relevant to sexual dysfunction includes a history of depression, anxiety, disordered sleep, or other psychiatric illness.31 Major life stressors and relationship dynamics should be discussed.102,124 Any history of abuse (physical, sexual, verbal, or emotional), sexual trauma, or domestic violence should also be sensitively explored.118

Physical Examination

Although physical examination findings can be normal in patients with sexual dysfunction, it is important to do a thorough evaluation to identify pathologic conditions as well as to educate patients about what is normal for their disability or disease state.79 A comprehensive examination includes determination of height, weight, and vital signs; auscultation of the heart and lungs; examination of the thyroid, lymph nodes, breasts, and abdomen; a check of peripheral pulses; evaluation for lower extremity edema; a neurologic examination; and a thorough genital examination.205,244 In particular, it is important to look for signs of cardiovascular disease (obesity, hypertension, diminished peripheral pulses, lower extremity edema) and endocrinopathies (thyromegaly, gynecomastia).31

The neurologic examination should include mental status, motor, and sensory testing; measurement of the range of motion of joints; and evaluation of muscle tone and reflexes.244 Range-of-motion measurements of the hips, knees, shoulders, and hands are particularly important. It is necessary to note whether the patient has UMN or LMN findings. Sensory testing should include light touch, pinprick, and proprioception in the lower limbs.244 Paying particular attention to the sensory evaluation of T11–L2 and S2–S5 is especially important because they represent the sympathetic and parasympathetic outflow tracts.222,244 Reflexes should be checked in the upper and lower limbs. The anal wink and bulbocavernosus reflexes both evaluate the integrity of the pudendal nerve and should be performed in both men and women.175,205

In men the genital examination consists of examining the penis for lesions and urethral position.205 The penis should also be palpated in the stretched position to detect fibrous plaques consistent with Peyronie’s disease.31 The testes should be checked for size, masses, and position, and the rectum evaluated for sphincter tone, pelvic floor muscle tenderness and strength, prostate size, masses, and lesions.205,244

In the genital examination of women, it is important to check for the appearance of the external genitalia, inflammation or atrophy of the vulva, episiotomy or childbirth laceration scarring or strictures, and external dermatologic lesions.118,124 A vaginal examination with one or two fingers inserted into the vagina is a good way to assess many of the common problems associated with female sexual dysfunction.244 Vaginismus can be appreciated by resistance or inability to insert a finger into the vagina.118 Tenderness of the levator ani and obturator internus muscles can be assessed, as well as pelvic floor muscle strength, coordination, and hypotonicity or hypertonicity.79,244 The presence of pelvic organ prolapse should be noted.119 Bimanual examination can be performed to assess for uterine and adnexal abnormalities, including tenderness and masses.118,124 Rectal examination should also be performed to assess for anal sphincter muscle tone, pelvic floor muscle tenderness, and voluntary and involuntary pelvic floor muscle contraction and relaxation ability.244

In both women and men the practitioner should check for signs of infection or sexually transmitted diseases, including discharge, rashes, or ulcerations.118

Diagnostic Evaluation

A large number of laboratory tests, as well as specialized diagnostic procedures, can be used to determine the pathologic origin of a patient’s sexual dysfunction. In general, however, the selection of treatment options is based on the presenting complaint and not the etiology behind the sexual dysfunction. Consequently complicated diagnostic testing is usually unnecessary. Recommended laboratory testing for all men and women with sexual dysfunction includes a complete blood cell count, chemistry panel, fasting blood glucose level, and fasting lipid profile.100,118 Other laboratory testing can be warranted based on the history and physical examination findings, including thyroid studies and serum free testosterone, prolactin, and prostate-specific antigen levels.8,31,100,164,205 Measurement of other sex hormones such as estrogen, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, or total testosterone has been shown to have far less utility in a majority of cases.8,164 Vaginal wet mount testing or screens for gonorrhea, chlamydia, or human immunodeficiency virus can be done if infection is clinically suspicted.118

For men with ED, a variety of specialized diagnostic procedures are used to determine the specific etiology of disease, usually in preparation for surgical treatment.100 The utilization of these tests has declined since the advent of oral PDE-5 inhibitor medications, with their ease of use, high level of effectiveness, and low side effect profile. The procedures include penile color duplex ultrasound, nocturnal penile tumescence monitoring, pharmacoarteriography, pharmacocavernosometry or pharmacocavernosography (PHCAS or PHCAG), and electrodiagnostic testing.86 Penile color duplex ultrasound is the most practical and commonly used diagnostic modality. It is a good tool to diagnose vasculogenic ED and is minimally invasive.86 Nocturnal penile tumescence measures sleep-related erections and has traditionally been used to distinguish psychogenic and organic ED.85,100 Penile pharmacoarteriography, PHCAS or PHCAG, and electrodiagnostic testing such as dorsal nerve stimulation or somatosensory evoked potentials are more invasive and time-consuming and are rarely used.85,225

In women, pelvic ultrasound can be indicated if uterine or adnexal pathologic disorders are suspected. The use of objective measures of genital blood flow, as measured by vaginal photoplethysmography, and advanced imaging techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging are currently primarily limited to the research setting.8,131

Treatment of Sexual Dysfunction

Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder in Men

Very little research has been done about HSDD in men, so little is known about treatment options. Secondary HSDD in men is thought to develop most frequently in response to another type of sexual dysfunction, usually ED or PE.150 It follows that treatment of the primary sexual dysfunction would improve desire. Secondary HSDD is also often related to medication side effects, so changing the drug dose or category will often improve the patient’s sexual drive. Primary HSDD is thought to relate to a “sexual secret” such as a variant arousal pattern (e.g., a man who is aroused by Internet pornography but not by his partner), a preference for masturbatory sex over partner sex, a history of poorly processed sexual trauma, or conflict about sexual orientation.150 Treating these psychosocial factors and getting the patient to be honest with himself and his partner about his true motivations will be helpful.

Hypogonadism and low testosterone levels certainly contribute to HSDD in men, and treatment with testosterone supplementation is beneficial.157 It is less clear whether treatment with testosterone in eugonadal men with HSDD can improve their sexual drive, but at least two studies have shown this to be the case.16,171

Erectile Dysfunction

The treatment of ED was revolutionized in 1998 with Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of sildenafil, the first of the now ubiquitous PDE-5 inhibitors, which have low side effect profiles and excellent efficacy across the spectrum of disease states that cause ED.141 Three PDE-5 inhibitors are currently approved for use: sildenafil (Viagra), vardenafil (Levitra), and tadalafil (Cialis). Sil-denafil and vardenafil have similar pharmacokinetics, with an onset of action within 30 to 120 minutes and a duration of efficacy of 4 to 5 hours.71 Tadalafil has an onset of action of 30 to 60 minutes and a duration of efficacy of 12 to 36 hours.71 Tadalafil has been approved for on-demand or daily dosing.71 PDE-5 inhibitors have been studied and proven effective in patients with cardiovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, SCI, MS, and depression.71 PDE-5 inhibitors have been reported to significantly improve erectile function in 60% to 70% of patients.101 Men with SCI achieve 80% success rates.65,88 Side effects reported with PDE-5 inhibitors include headache, flushing, rhinitis, back pain, hearing loss, and visual loss in the form of nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy.71 These medications are strictly contraindicated in patients taking nitrates for chest pain.141 New PDE-5 inhibitors such as avanafil, udenafil, and mirodenafil are currently undergoing clinical trials.101

PDE-5 inhibitors are known to be less effective in patients with very severe ED, uncontrolled diabetes with neuropathy, and severe vascular disease, and in those who have undergone radical prostatectomy. Currently few other oral agents show treatment benefit. The ones currently available include sublingual apomorphine and yohimbine.141 Bremelanotide, a melanocortin receptor agonist, was efficacious in multiple clinical trials, including in patients who had been unsuccessfully treated with sildenafil.198,211 Development of this drug was halted in 2008 after concerns arose over the side effect of increased blood pressure. Future oral therapies potentially include other melanocortin receptor agonists, dopamine receptor agonists, and Rho-kinase inhibitors.101

Second-line treatments after PDE-5 inhibitor treatment failure include intracavernosal injection therapy, intraurethral alprostadil (medicated urethral system for erection [MUSE]) therapy, topical alprostadil, and vacuum constriction devices.

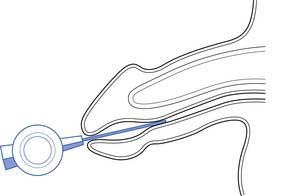

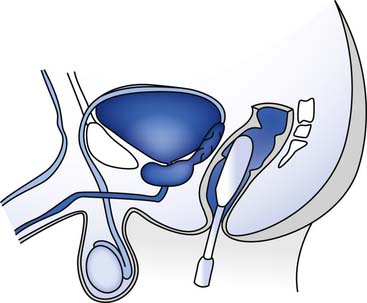

Intracavernosal penile injections have been used for decades, with treatment satisfaction rates of 87% to 93.5%, relatively few adverse effects, and a rapid onset of action (Figure 31-5).71,141 High discontinuation rates have been noted, and the complications that can occur include priapism and Peyronie’s disease.71 The most commonly injected medications are alprostadil, papaverine, and phentolamine in various combinations.141

Intraurethral treatment of alprostadil with the MUSE system can be an alternative in patients who cannot take PDE-5 inhibitors and who do not want to try intracavernosal injection therapy (Figure 31-6). Its efficacy is only 30%, and it rarely has been associated with hypotension and syncope.71,141 Topical alprostadil formulations are currently undergoing clinical trials with modest efficacy results, but with side effects of penile burning and partner vaginal pain.101

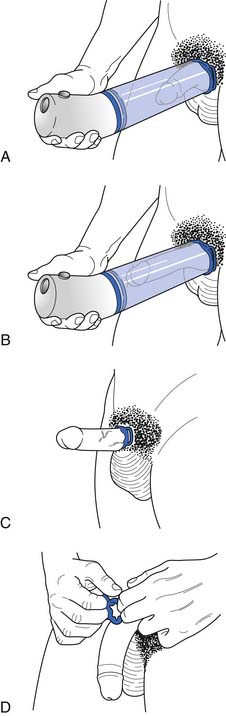

Vacuum constriction devices apply a negative pressure to draw blood into the corpora cavernosa, which is then retained by the application of a constriction band at the base of the penis (Figure 31-7).141 Efficacy rates are as high as 90%, but satisfaction rates tend to be lower because of penile pain and trapped ejaculate.71 Anticoagulant therapy is a relative contraindication.141 These devices are often preferred in men who do not want to take medications. The constriction band cannot be left in place longer than 30 minutes because of the risk for ischemia, especially in patients who are insensate such as those with SCI.71

Third-line treatments for ED include surgical options such as penile prostheses (Figure 31-8). Penile prostheses come in two types: semirigid (malleable) and inflatable. Semirigid prostheses have malleable silicone elastomer rods with central metal cables that can be bent or straightened to produce an erection.71 Inflatable prostheses have cylinders that are implanted into the corpora cavernosa, a reservoir with fluid, and a pump that is placed in the scrotum.71 Erection is achieved by compressing the scrotal pump to transfer fluid from the reservoir to the cylinders.71 Infection rates have been reduced to approximately 1% because of antibiotic and hydrophilic coatings that are now available on the prostheses.71 Mechanical failure rates are 5% at 1 year, 20% by 5 years, and 50% at 10 years.141

Premature Ejaculation

The mainstay of treatment until recently for PE was cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and psychologic counseling. Various CBT approaches include the start-pause and frenulum squeeze techniques, as well as experimentation with positioning, rhythm, speed, breathing, and depth of penile penetration.176,193 These strategies have success rates of up to 70% in the short-term, but long-term treatment satisfaction has only been reported at 25% to 60%.193 Cognitive-behavioral approaches to treatment are often very time-consuming, expensive, and perceived as intrusive and mechanistic, affecting intimacy and spontaneity during a sexual encounter.176,193

Although no medications are FDA approved for the treatment of PE, many pharmacologic approaches have been well studied and show significant benefit. (It should be noted that the following medications are “off-label” for the treatment of PE.) SSRIs are the most commonly used medications for PE, with paroxetine being the most effective, followed by fluoxetine and sertraline.195 The TCA clomipramine has also been used successfully, but anticholinergic side effects limit its tolerance.176 Both SSRIs and clomipramine are usually given daily because of their slow onset of action (5 hours), long half-lives, and long treatment time (up to 4 weeks) to achieve a steady-state.176,195

On-demand treatment for PE has been the holy grail of research into this disorder, and some recent advances have been promising. Conventional SSRIs have been studied for “as-needed” use, and results have been mixed.195 Dapoxetine is a new, short-acting SSRI developed specifically for as-needed use for PE. It achieves a peak plasma concentration within 1 hour and has a half-life of 1.5 hours.176 It has been shown to significantly increase the time to ejaculation and improve patient satisfaction.120,176 Dapoxetine has been approved for use in some European countries, but is not yet available in the United States. Tramadol has also been shown to be an excellent on-demand treatment for PE, with one study showing a 13-fold increase in mean time to ejaculation.195,197 Topical agents such as lidocaine or EMLA cream can be helpful by decreasing sensory perception in the penis, thereby prolonging ejaculation.195

Anejaculation and Anorgasmia in Men

Assisted ejaculation methods that have been proven effective for fertility treatment in men with SCI, MS, and other disabilities include penile vibratory stimulation (PVS) and rectal probe electroejaculation (EEJ) (Figures 31-9 and 31-10).228 PVS is the most commonly used technique because it is able produces superior sperm quality, is more comfortable and preferable to patients, and can be used in a home setting.58,183 PVS only produces ejaculation in 60% to 80% of cases, whereas EEJ is 80% to 100% successful.183 EEJ is usually only used in patients in whom PVS has been unsuccessful, because it produces lower quality semen, must be conducted in a physician’s office setting, and often requires the use of anesthesia to perform the procedure and retrieve ejaculate.58,183 Chemically assisted ejaculation is also a possibility, particularly with the use of midodrine to improve ejaculation success rates in combination with PVS.59 A recent study showed that vardenafil can improve the ejaculation rate in men with SCI.87 Care must be taken to monitor blood pressure and look for signs of autonomic dysreflexia in spinal cord–injured men undergoing assisted ejaculation.2

FIGURE 31-9 Vibrator disc position during penile vibratory stimulation.

(Redrawn from Sonksen J, Ohl DA: Penile vibratory stimulation and electro-ejaculation in the treatment of ejaculatory dysfunction, Int J Androl 25:324, 2002.)

FIGURE 31-10 Rectal probe position during an electroejaculation procedure.

(Redrawn from Sonksen J, Ohl DA. Penile vibratory stimulation and electroejaculation in the treatment of ejaculatory dysfunction, Int J Androl 25:324, 2002.)

Ejaculatory and orgasmic dysfunction in men is much harder to treat when the goal is enhanced sexual function as opposed to fertility. Pharmacologic treatment for ejaculatory and orgasmic dysfunction in men is still largely unproven, although there have been some case series and small controlled trials with sildenafil, bupropion, amantadine, buspirone, cyproheptadine, and yohimbine that showed modest benefits.153,161 Cognitive-behavioral modification and psychotherapy are indicated in men with psychogenic (situational or relational) orgasmic dysfunction.141

Priapism

Low-flow (or ischemic) priapism is a medical emergency, and patients with an erection lasting greater than 4 hours should be directed to go to the nearest hospital without delay. Treatment is usually through decompression of the corpora by the slow aspiration of blood over a 1-hour period, followed by injection of an α-adrenergic agonist to cause contraction of the smooth muscle.141 High-flow and stuttering priapism are usually benign conditions that are self-limiting and do not require treatment.141

Peyronie’s Disease

Surgical excision of fibrous plaque and correction of penile curvature is the criterion standard for treatment of Peyronie’s disease, but should only be undertaken once the disease has been stable for more than 6 months to ensure long-term efficacy.234 Intralesional injection of verapamil has been proven beneficial in multiple randomized controlled trials.226 Other therapies with less proven success records include oral medication administration (including colchicines and aminobenzoate potassium [Potaba]), intralesional injections of varied medications, iontophoresis, and extracorporeal shock wave therapy.226,234

Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder in Women

When considering treatment for women with low sexual desire, it is important to remember that the sexual desire of women is very different from that of men and is also very different from what is often portrayed in the medical literature. Many women experience only responsive, as opposed to spontaneous, sexual desire.22 The first step in treating a woman with a complaint of low sexual desire is educating her as to what is normal for women, because there are many misconceptions fueled by popular culture about what a woman should feel.79 Referring the patient to the work of Dr. Rosemary Basson is often very enlightening.19,21,22

The major pharmacologic treatment for HSDD in women is testosterone therapy. Many treatment preparations are available, but a transdermal patch is the most commonly studied and prescribed.1 Many studies have confirmed the effectiveness of transdermal testosterone for increasing sexual desire and satisfaction in postmenopausal women or “surgically menopausal” women who have had bilateral oophorectomies. Few studies, however, have been conducted in those who are premenopausal.42,74,214 Side effects are usually related to masculinization, such as with hirsutism and acne. The FDA has not approved the use of testosterone to treat HSDD in women despite its effectiveness and relatively low side effect profile, largely because long-term safety data have not been established.74 Theoretically testosterone administration might increase the risk for breast cancer, and a recent study that monitored women for 52 weeks of continuous use of a testosterone patch did find a possible slight increased risk for breast cancer in the treatment population.64 Other concerns with long-term use include the effect on lipid profiles and cardiovascular health.1 Further research on the use of testosterone in women is necessary.

Other medications that show promise for treating HSDD in women include tibolone (a synthetic steroid) and melanocortins.68,149,211

Female Arousal Disorder

Lack of subjective feelings of arousal and inadequate vaginal lubrication during sexual activity have traditionally been linked more with psychosocial factors than with organic etiologies. Sexual behavioral techniques, sex therapy, and couple’s counseling (originally conceived by Masters and Johnson147) have proven benefit by helping to reduce anxiety and exaggerated sexual expectations.149

Pharmacologic interventions for female arousal disorders have been increasingly studied in recent years, with mixed results. Given that the physiology of female arousal should theoretically parallel that of male erectile function, there was much anticipation that sildenafil would prove to be a promising treatment option. Research trials have been largely disappointing, however, especially compared with the effectiveness of PDE-5 inhibitors in men with ED. The medication has been well tolerated, but the overall summation of research conducted to date does not show a benefit for sildenafil in most women with generalized arousal disorder without a known organic cause.149,213 In women with disabilities, however, PDE-5 inhibitors remain a viable treatment option, because trials have been positive in limited, small populations of women with acquired genital arousal disorder of an organic nature (premenopausal type 1 diabetics, spinal cord–injured women, patients with MS, and women taking SSRIs).51,149,169,224 More research is needed on PDE-5 inhibitors in women, both with and without acquired disabilities.

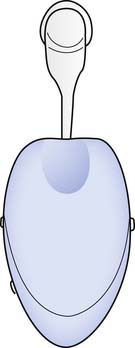

Other medications have shown more promise than sildenafil for female arousal disorder in the general population, particularly in postmenopausal women. These include melanocortins, phentolamine, L-arginine, and alprostadil.∗ Acquired arousal disorder in postmenopausal women is often treated with systemic or local estrogen therapy to improve vaginal lubrication and blood flow.125 Mechanical devices can also aid in increasing arousal, including vibratory stimulators and the Eros Clitoral Therapy Device, a clitoral vacuum that has been approved by the FDA to augment female arousal and orgasm (Figure 31-11).36

Female Orgasmic Dysfunction

Female orgasmic dysfunction in the absence of a concomitant arousal disorder is usually considered to be a psychogenic problem. Beneficial treatments include CBT (to focus on decreasing anxiety and promoting changes in attitudes and sexual thoughts), sensate focus therapy (which guides a woman and her partner through a series of exercises with increasing levels of sexual intimacy), and directed masturbation (educating a woman that masturbation is healthy and normal, and having her use self-stimulation to discover what is effective for her).79,125 These behavioral treatments have been shown to be effective in 60% of women.155 Bupropion has been shown in at least one study to help orgasmic dysfunction in women.161 As with decreased arousal, mechanical devices can help with attainment of orgasm.36

Dyspareunia

Vulvodynia and vestibulodynia (formerly known as vulvar vestibulitis syndrome) can be treated through a variety of treatment modalities. Topical 5% lidocaine ointment has been proven effective to provide symptomatic relief in up to 57% of patients, and is especially useful if applied overnight or 30 minutes before sexual intercourse.91,245 Oral medications such as tricyclic and other antidepressants, and gabapentin have all been demonstrated to be similarly successful in treating women with vulvar pain, with improvement in 47% to 54%.91,179 Pelvic floor physical therapy, vaginal surface electromyographic biofeedback, or a combination of these treatments has been shown to be successful in 35% to 86% of patients (Figure 31-12).32,33,81,90,100 Trigger point and botulinum toxin type A (Botox) injections have been reported to provide modest benefits, but are poorly tolerated by the patients.91 Surgical vestibulectomy has high rates of treatment success for vestibulodynia, with an average reported response rate of at least 80%, but should only be reserved for chronic cases in which conservative treatment has been unsuccessful.91 Five percent of surgical patients have worsened pain after vestibulectomy, particularly when they have levator ani hypertonia present on physical examination before surgery.91,179

Vaginismus

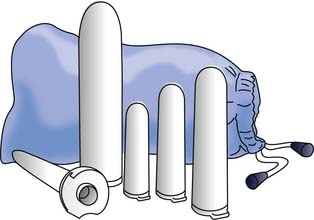

The treatment of choice for vaginismus has traditionally been one of systematic desensitization to the fear of vaginal penetration.125 In this approach the patient slowly progresses from self-touch at the introitus to insertion of a finger into the vagina, and then uses various-sized vaginal dilator inserts to progressively increase the diameter of her vagina (Figure 31-13).241 The eventual easing of vaginal tightness is thought to be the result of the gradual reduction in reflex protective involuntary pelvic floor muscle contractions.241 As patients with vaginismus often have accompanying pelvic floor myofascial pain and levatorani hypertonia, physical therapists can also employ myofascial release techniques and pelvic surface electromyographic biofeedback to help the patient learn to release levator ani tightness.81,95 Adjunctive psychotherapy is often useful to help the patient overcome her fears and deal with any past psychologic trauma such as a history of abuse.79,133

1. Abdallah R.T., Simon J.A. Testosterone therapy in women: its role in the management of hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Int J Impot Res. 2007;19(5):458-463.

2. Abdel-Nasser A.M., Ali E.I. Determinants of sexual disability and dissatisfaction in female patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25(6):822-830.

3. Addis I.B., Ireland C.C., Vittinghoff E., et al. Sexual activity and function in postmenopausal women with heart disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:121-127.

4. Aguirre M.A., Velez A., Romero M., et al. Gynecomastia and sexual impotence associated with methotrexate treatment. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(8):1793-1794.

5. Alexander C.J., Sipski M.L., Findley T.W. Sexual activities, desire, and satisfaction in males pre- and post-spinal cord injury. Arch Sex Behav. 1993;22(3):217-228.

6. Alexander M., Rosen R.C. Spinal cord injuries and orgasm: a review. J Sex Marital Ther. 2008;34(4):308-324.

7. Amahd S. Disopyramide and impotence [letter to the editor]. South Med J. 1980;73:958.

8. Amato P. Categories of female sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2006;33(4):527-534.

9. Ambler N., Williams A.C., Hill P., et al. Sexual difficulties of chronic pain patients. Clin J Pain. 2001;17(2):138-145.

10. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

11. American Psychiatric Association. DSM-V: the future manual. http://www.psych.org/dsmv.asp. AvailableAccessed April 19, 2009

12. Ashton A.K., Hamer R., Rosen R.C. SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction and its treatment: a large-scale retrospective study of 596 psychiatric outpatients. J Sex Marital Ther. 1997;23(3):165-175.

13. Aslan E., Fynes M. Female sexual dysfunction. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(2):293-305.

14. Atmaca M., Kuloglu M., Tezcan E. A new atypical antipsychotic: quetiapine-induced sexual dysfunctions. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17(2):201-203.

15. Axel S.J. Spinal cord injured women’s concerns: menstruation and pregnancy. Rehabil Nurs. 1982;7(5):10-15.

16. Bagatell C.J., Heiman J.R., Matsumoto A.M., et al. Metabolic and behavioral effects of high-dose testosterone in healthy men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:561-567.

17. Bartlik B., Kocsis J.H., Legere R., et al. Sexual dysfunction secondary to depressive disorders. J Gend Specif Med. 1999;2:52-60.

18. Bartlik B.D., Rosenfeld S., Beaton C. Assessment of sexual functioning: sexual history taking for health care practitioners. Epilepsy Behav. 2005;7(suppl 2):S15-S21.

19. Basson R. The female sexual response: a different model. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:51-65.

20. Basson R. Female sexual response: the role of drugs in the management of sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(2):350-353.

21. Basson R. Human sex-response cycles. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27:33-43.

22. Basson R. Using a different model for female sexual response to address women’s problematic low sexual desire. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27(5):395-403.

23. Basson R. Women’s sexual dysfunction: revised and expanded definitions. CMAJ. 2005;172:1327-1333.

24. Basson R. Testosterone supplementation to improve women’s sexual satisfaction: complexities and unknowns [comment]. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(8):620-621.

25. Basson R. Women’s sexual function and dysfunction: current uncertainties, future directions. Int J Impot Res. 2008;20(5):466-478.

26. Basson R., Althof S., Davis S., et al. Summary of the recommendations on sexual dysfunctions in women. J Sex Med. 2004;1(1):24-34.

27. Basson R., Berman J., Burnett A., et al. Report of the International Consensus Development Conference on Female Sexual Dysfunction: definitions and classifications. J Urol. 2000;163(3):888-893.

28. Basson R., Leiblum S., Brotto L., et al. Revised definitions of women’s sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2004;1(1):40-48.

29. Basson R., Weijmar Schultz W. Sexual sequelae of general medical disorders. Lancet. 2007;369(9559):409-424.

30. Basu A., Ryder R.E.J. New treatment options for erectile dysfunction in patients with diabetes mellitus. Drugs. 2004;64(23):2667-2688.

31. Beckman T.J., Abu-Lebdeh H.S., Mynderse L.A. Evaluation and medical management of erectile dysfunction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:385-390.

32. Bergeron S., Binik Y.M., Khalife S., et al. A randomized comparison of group cognitive-behavioral therapy, surface electromyographic biofeedback, and vestibulectomy in the treatment of dyspareunia resulting from vulvar vestibulitis. Pain. 2001;91(3):297-306.

33. Bergeron S., Brown C., Lord M.J., et al. Physical therapy for vulvar vestibulitis syndrome: a retrospective study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28:183-192.

34. Bernardo A. Sexuality in patients with coronary artery disease and heart failure. Herz. 2001;26:353-359.

35. Bilgic A., Gurkan K., Turkoglu S. Excessive masturbation and hypersexual behavior associated with methylphenidate. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(7):789-790.

36. Billups K.L. The role of mechanical devices in treating female sexual dysfunction and enhancing the female sexual response. World J Urol. 2002;20(2):137-141.

37. Binik Y.M., Reissing E., Pukall C., et al. The female sexual pain disorders: genital pain or sexual dysfunction? Arch Sex Behav. 2002;31(5):425-429.

38. Blake D.J., Maisiak R., Alarcon G.S., et al. Sexual quality-of-life of patients with arthritis compared to arthritis-free controls. J Rheumatol. 1987;14(3):570-576.

39. Blocker W.P. Coronary heart disease and sexuality. Phys Med Rehabil State Art Rev. 1995;9:387-399.

40. Bond M.R. Assessment of the psychosocial outcome of severe head injury. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1976;34:57-70.

41. Bors E., Comarr A.E. Neurological disturbances of sexual function with special reference to 529 patients with spinal cord injury. Urol Surv. 110(191-221), 1960.

42. Braunstein G.D., Sundwall D.A., Katz M., et al. Safety and efficacy of a testosterone patch for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in surgically menopausal women: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial [see comment]. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(14):1582-1589.

43. Breckinridge A. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and quality of life. Am J Hypertens. 1991;4:79S-82S.

44. Bretschneider J.G., McCoy N.L. Sexual interest and behavior in healthy 80- to 102-year-olds. Arch Sex Behav. 1988;17(2):109-129.

45. Brichart N., Delavierre D., Peneau M., et al. [Priapism associated with antipsychotic medications: a series of four patients]. Prog Urol. 2008;18(10):669-673. (French)

46. Britton K.R. Case study medroxyprogesterone in the treatment of aggressive hypersexual behaviour in traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 1998;12:703-707.

47. Brown R., Balousek S., Mundt M., et al. Methadone maintenance and male sexual dysfunction. J Addict Dis. 2005;24(2):91-106.

48. Buckwalter K.C., Wernimont T., Buckwalter J.A. Musculoskeletal conditions and sexuality (part I). Sex Disabil. 1982;4(3):131-142.

49. Burchardt M., Burchardt T., Baer L., et al. Hypertension is associated with severe erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2000;164:1188-1191.

50. Burk K., Weiss A. Impotence after recovery from Guillain-Barré syndrome. N J Med. 1998;95:31-34.

51. Caruso S., Rugolo S., Agnello C., et al. Sildenafil improves sexual functioning in premenopausal women with type 1 diabetes who are affected by sexual arousal disorder: a double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1496-1501.

52. Carvajal A., Martin Arias L.H. Gynecomastia and sexual disorders after the administration of omeprazole. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90(6):1028-1029.

53. Charlifue S., Gerhart K.A., Menter R.R., et al. Sexual issues of women with spinal cord injuries. Paraplegia. 1992;30:192-199.

54. Cheung R.T. Update on medical and surgical management of intracerebral hemorrhage. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2007;2:174-181.

55. Cheung R.T. Sexual dysfunction after stroke: a need for more study. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15(7):641.

56. Clayton A. Recognition and assessment of sexual dysfunction associated with depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 3):5-9.

57. Coslett H.B., Heilman K.M. Male sexual function. Impairment after right hemisphere stroke. Arch Neurol. 1986;43:1036-1039.

58. Courtois F.J., Charvier K.F., Leriche A., et al. Blood pressure changes during sexual stimulation, ejaculation and midodrine treatment in men with spinal cord injury. BJU Int. 2008;101(3):331-337.

59. Crenshaw T.L. The sexual aversion syndrome. J Sex Marital Ther. 1985;11:285-292.

60. Currey H.L. Osteoarthrosis of the hip joint and sexual activity. Ann Rheum Dis. 1970;29(5):488-493.

61. Dachille G., Ludovico G.M., Pagliarulo G., et al. Sexual dysfunctions in multiple sclerosis. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 2008;60(2):77-79.

62. Dalal A., Zhou L. Gabapentin and sexual dysfunction: report of two cases. Neurologist. 2008;14(1):50-51.

63. Daniell H.W. Hypogonadism in men consuming sustained-action oral opioids. J Pain. 2002;3(5):377-384.

64. Davis S.R., Moreau M., Kroll R., et al. Testosterone for low libido in postmenopausal women not taking estrogen [see comment]. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(19):2005-2017.