18.1 Sexual assault

Introduction

Assessment of child sexual assault (CSA) requires a dedicated, well-trained and experienced doctor who is able to spend a significant amount of time making an unhurried and thorough assessment and detailed documentation of history and examination findings. The doctor must have an accurate knowledge of genital anatomy, and experience in performing gynaecological examinations. Skills and experience in this field are developed through postgraduate studies, significant case numbers, a knowledge of current literature and involvement in peer-review practices.3

Inexpert assessment of such cases may have a profound negative influence on the child and family. It may potentially lead to inappropriate removal of the child from the family or wrongful imprisonment.4

Definitions

CSA is the use of a child for sexual gratification by an adult or significantly older child/adolescent.5 It may involve a range of activities that vary from exposing the child to sexually explicit materials to anal or vaginal penetration of the child. Central to the definition is the limitation of the child to provide truly informed consent for sexual activity with adults.

Sexual play between children of similar age does not fit into this description.

Epidemiology of CSA

There has been a significant increase in the recognition of CSA,3,11,12 which has been reflected by a substantial increase in the number of reports made to child protection services across Australia and overseas, particularly in the last 5 years.

Sexual assault has been documented as occurring on children of all ages and both sexes, and is committed predominantly by men, who are commonly members of the child’s family, family friends or other trusted adults in positions of authority.11

The estimated proportion of children exposed to some form of sexual assault varies depending on the definition of sexual abuse and methodology used. In the United States, literature surveys provide estimates of 9–52% for females and 3–10% for males.6 There is no comprehensive comparative Australian literature.

CSA and emergency medicine

Children who are victims of sexual assault may present to EDs in a variety of circumstances:

They may be seen for an unrelated matter when routine history and physical examination produce information where sexual assault forms part of the differential diagnosis.

They may be seen for an unrelated matter when routine history and physical examination produce information where sexual assault forms part of the differential diagnosis.Recognition of CSA

History from the child remains the single most important diagnostic feature in coming to the conclusion that a child has been sexually abused.13

Genitoanal injury

Only 4% of all children referred for medical evaluation of sexual abuse have abnormal examinations at the time of evaluation. Even with a history of severe abuse, such as vaginal or anal penetration, the rate of abnormal medical findings is only 5.5%.13

When the alleged sexual abuse has occurred within 72 hours, or there is bleeding or acute injury, the examination should be performed immediately. In this situation, protocols for CSA victims should be followed to secure biological trace evidence such as epithelial cells, semen, and blood, as well as to maintain a ‘chain of evidence’. When more than 72 hours has passed and no acute injuries are present, an emergency examination usually is not necessary. An evaluation, therefore, should be scheduled at the earliest convenient time for the child, physician, and investigative team.17

Genital findings in children are difficult to interpret. Such interpretation is generally beyond the expertise of most emergency physicians.14 Whilst acute trauma may be easily recognised, interpretation of such findings may be problematic for the occasional examiner.14

Sexually transmitted diseases

The diagnosis of a sexually transmitted disease in a child may be highly suggestive but is not diagnostic of sexual contact. Rectal and genital Chlamydia infections in young children may be due to a persistent perinatally-acquired infection, which may last for up to 3 years.15,16

Diagnostic considerations

On examination, findings which are suggestive, but not diagnostic, of CSA include:

Role of the emergency physician

Mandatory reporting legislation

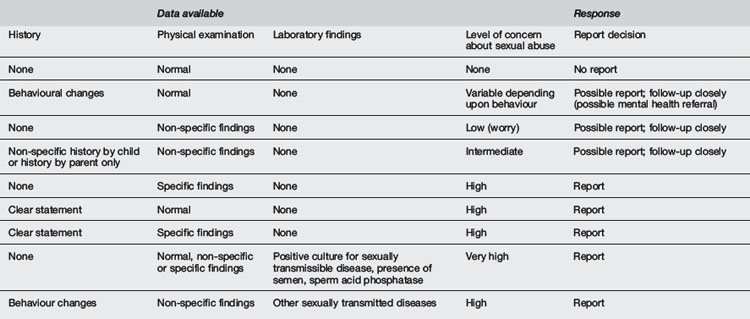

Some form of mandatory reporting legislation exists in all Australian jurisdictions. Although this legislation varies from state to state, the basic principles are similar. Doctors are mandated to report cases where there is reasonable suspicion that CSA will occur, or is occurring, and the guardian is unlikely to prevent such acts (Table 18.1.1). The reporting practitioner has statutory protection from prosecution if a report is made in good faith.

1 American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Adolescence. Sexual assault and the adolescent. Paediatrics. 1994;94:761-765.

2 American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameters for the forensic evaluation of children and adolescents who may have been physically or sexually abused. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:423-442.

3 Donald T., Wells D. Graduate Diploma in Forensic Medicine, Subject guide. Melbourne: Monash University Centre for Learning and Teaching Support. 2000:253.

4 Butler-Sloss E. Report of the Enquiry into Child Abuse in Cleveland 1987. London: HMSO; 1988.

5 Kempe C.H. Sexual abuse, another hidden paediatric problem: The 1977 C. Anderson Aldrich lecture. Paediatrics. 1978;62:382-389.

6 Tomison A. Update on child sexual abuse. National Child Protection Clearinghouse; 1995. Issues in child abuse prevention number 5. Available from http://www.aifs.gov.au/nch/pubs/issues/issues5/issues5.html [accessed 26.10.10]

7 Adams J.A., Harper K., Knudson S., Revilla J. Examination findings in legally confirmed child sexual abuse: It’s normal to be normal. Paediatrics. 1994;94:310-317.

8 Finkel M.A. Anogenital trauma in sexually abused children. Paediatrics. 1989;84:317-322.

9 McCann J., Voris J., Simon M. Genital injuries resulting from sexual abuse: A longitudinal study. Paediatrics. 1992;89:307-317.

10 McCann J., Voris J. Perianal injuries resulting from sexual abuse: A longitudinal study. Paediatrics. 1993;91:390-397.

11 Finkelhor D. The international epidemiology of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 1994;18(5):409-417.

12 Leventhal J.M. Epidemiology of child sexual abuse. In: Oates R.K., editor. Understanding and managing child sexual abuse. Sydney: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1990.

13 Heger A., Ticson L., Velasquez O., Bernier R. Children referred for possible sexual abuse: Medical findings in 2384 children. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26(6–7):645-659.

14 Makoroff K.L., Brauley J.L., Brandner A.M., et al. Genital examinations for alleged sexual abuse of prepubertal girls: Findings by pediatric emergency medicine physicians compared with child abuse trained physicians. Child Abuse Negl. 2002;26(12):1235-1242.

15 Hammerschlag M.R. Sexually transmitted diseases in sexually abused children. Adv Pediatr Infect Dis. 1988;3:1-18.

16 Hammerschlag M.R., Doraiswamy B., Alexander E.R., et al. Are rectogenital chlamydial infections a marker of sexual abuse in children? Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1984;3:100-104.

17 American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children. Guidelines for psychosocial evaluation of suspected sexual abuse in young children. Chicago, IL: American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children; 1990.