Sexual Assault

Perspective

Sexual violence is a significant problem in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have defined it as sexual activity in which consent is not obtained or not freely given. It pertains to a wide variety of sexual conduct and may entail, but does not require, penetration, completion, or, in certain cases, physical contact (e.g., voyeurism).1 Referred to in statute as sexual assault, it is explicated more precisely by state and local governments. Emergency physicians should be aware of local, state, and federal laws because emergency physicians may be mandated reporters and involved in the evaluation, treatment, evidence collection, and documentation of sexual assault.

Major advances in the evaluation and management of sexual assault victims (SAVs) have occurred over the past 30 years. The formation of community-based multidisciplinary teams that first took hold in California is probably the most important. The development of a sexual assault response team (SART) with representatives from the district attorney’s office, law enforcement officials, crime laboratory personnel, medical personnel, including both physicians and nurses, social service agents, and victim advocates came together as a group. These major players have sought to solve the logistic, medical, psychological, legal, and social problems incurred by SAVs. The commitment and mutual cooperation of the SART led to the development of standardized protocols for the care and treatment of SAVs. These protocols specify the procedures for interviewing and examining the SAV and collecting, preserving, and storing evidentiary materials, and include the evidence kit and forms for documentation. Many jurisdictions have adopted this standardized system, and in 2004 the first national protocol was released by the U.S. Department of Justice.2 With a protocol in place, the necessity of having trained forensic examiners (FEs), irrespective of academic credentials, is evident.3,4 Currently, this role subsumes that of the sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE); the ubiquitous, mostly hospital-based SANE programs have contributed substantially to our knowledge and understanding of sexual assault and have improved the care of the victims.5,6 In addition, because of the use of special technologies, including colposcopy, digital photography and videography, and the alternate light source (ALS), the establishment of designated examination centers for sexual violence is increasingly prevalent.7 Much information about the characteristics, physical examination findings, and correlates of injury in SAVs is now available. This information facilitates the management of the SAV, improves the experience of the victim, and ultimately assists in the identification of the perpetrator.

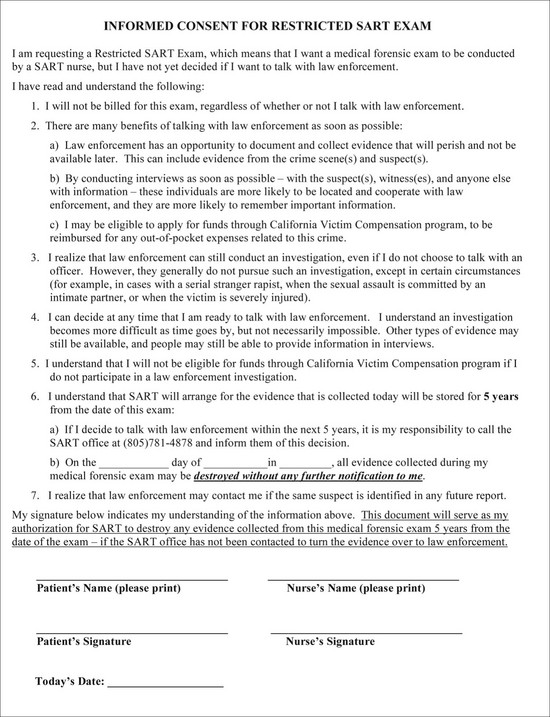

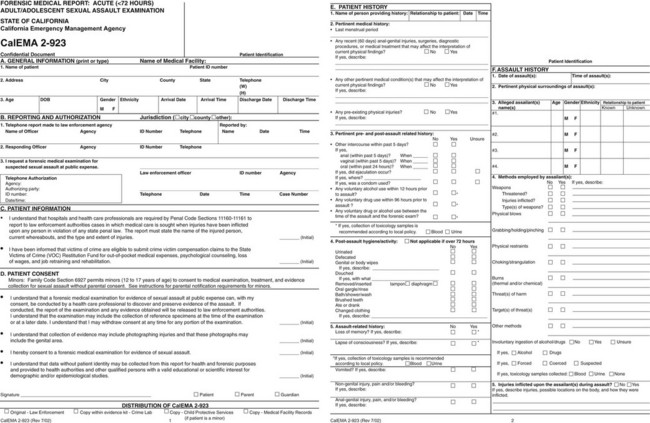

Although these changes began as a grassroots movement, a victim-centered, multidisciplinary team approach, including trained FEs, was codified by the federal government in the 1994 Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) and its subsequent iterations in 2000 and 2005. Forensic compliance issues for all states receiving grant monies from this bill began in 2009. Programs must now offer forensic examinations for all SAVs irrespective of whether they report or cooperate with law enforcement and with no out-of-pocket expenses to the SAV. This poses special problems for medical professionals practicing in states in which they are mandated reporters. As many as 18.5% of SAVs who delayed law enforcement involvement, changed their minds8; this raises multiple issues concerning evidence storage, as well as maintenance and chain of custody. Moreover, victim notification about the destruction of forensic evidence presents challenges in an anonymous system. Currently, health care facilities have no nationally regulated mandates, accreditation process, or quality assurance to address these specific problems. Allowing SAVs time to consider their options9–11 and providing them with high-quality health care12,13 have been shown to increase their cooperation with police investigations. (See Figure 67-1 for a sample of a form for special consent without law enforcement participation; also refer to www.ccfmtc.tv/pdfs/forms/CALEMA-924i.pdf for abbreviated examination form and protocol.)

Epidemiology

Based on national emergency department (ED) data, sexual assaults represented 10% of all assault-related injury visits to the ED by female patients in 2006. In 2007, for female individuals of all ages and for boys aged 1 to 9 years, sexual assault was the third leading cause of nonfatal violence-related injury.14 It is important to note that the cost of sexual violence to the health care system is high because it may include not only the initial visit for the crime but also subsequent visits for other health-related issues.7

Women remain the predominate victims (94%), although male victims tend to be victimized at an earlier age.15 Historically, sexual assault has been a largely unreported crime, with only about a third of SAVs coming forward. The major reasons for not reporting include not wanting the assailant to go to jail, having a prior relationship with the assailant, and feeling that the police would blame the victim or be insensitive. Some have sited fear of reprisal, including death, media attention, and shame, for their reluctance.16 The closer the relationship between the victim and offender, the less likely the SAV has been to report the crime17; the relationship between SAV and perpetrator is often absent in the medical record, yet it is critical for safety planning.18,19 A substantial number of SAVs report at or after 72 hours, and they are typically adolescents. There is a high positive correlation between reporting to the police and receiving medical treatment20; early intervention is key to diminishing adverse psychological and physical outcomes for the SAV.17,21

Sexual assault is an extremely common crime, with estimates of 1 in 6 females and 1 in 33 males being assaulted during their lifetime.15 The mean age of a female victim is approximately 20 years. She is most often single. Adolescents account for less than half of all victims seen, yet the incidence of sexual assault peaks in the age group of 16 to 19 years.22 For nearly 40% of victims, sexual assault is the first sexual experience.23 Eighty percent of the time, a person known to the victim perpetrates the assault.15 Former and current boyfriends are equally common as perpetrators, lending support to the position that leaving a violent partner does not always end the violence.19 The younger the victim, the more likely the perpetrator is to be a relative. The location of the sexual assault varies with the victim and the type of perpetrator. In general, adults are usually assaulted in their own home, whereas adolescents are more likely to be assaulted in the assailant’s residence.24 Stranger assaults are less common for both males and females15; they are more likely to involve adults, occur outdoors, and include the use of a weapon and have a greater likelihood of injury.25–27 Alcohol and drug use are common accompaniments to sexual assault.28 Other vulnerable populations include the mentally or physically disabled, the homeless, elderly individuals, sex trade workers, and those previously incarcerated.29,30 Higher rates of sexual assault also occur during college, military service, war, and natural disaster.31

Most assaults involve penile-vaginal penetration,32 and penile penetration is significantly associated with genital injury in females.33 Typically, digital-vaginal penetration is the second most common sexual act reported. Oral-genital contact occurs in less than 30%, with anal assault slightly less common.23,34–36 The use of a foreign object is unusual (10%) and associated with increased trauma.32,37 Anal assault is associated with increased violence,23,25,38,39 offender preference for anal sex,40 and offender problems with sexual dysfunction.41,42

Injury is not an inevitable consequence of sexual assault.4,43,44 Adolescent SAVs have been shown to sustain more anogenital injuries than their adult counterparts.26,32,45 Nongenital trauma occurs in 40 to 81% of SAVs, and its presence is associated with anogenital injury.39,45 For nongenital trauma, the extremities are the most commonly injured, followed by the head and neck.46 Serious injury involving hospitalization occurs in about 5%,7 and death associated with sexual assault is estimated at 1% or less, although this latter figure is probably a gross underestimate.38,47,48 Psychological distress and interpersonal difficulties are the major sequelae after sexual assault. These problems are exacerbated in SAVs with known attackers who delay reporting.21,49

Distinguishing Principles of Disease

Emergency Department Preparation

The ED should also be prepared for the unusual victim with significant or life-threatening injuries. In this instance the emergency physician needs to delegate the forensic responsibility to another forensically trained staff member whose sole purpose is to collect the evidence and, if required, follow the SAV to surgery. In cases in which there is substantial injury, following the patient from intake allows the examiner to understand better and document the nature and extent of the trauma and continue the forensic process with little further distress to the patient.50

Obtaining the History and Consent

Numerous consents should be obtained from the SAV, depending on state and local laws (Box 67-1). The FE should be knowledgeable about all statutes governing consent, including whether minors need parental consent. In some states, even if parental consent is not required, the FE may still be required to contact the parents and document the success or failure of this attempt. Most SAVs are concerned about access to the SART record and photographs, particularly when the SART examination facility is within the hospital setting. Keeping these records separate from the primary hospital chart system helps protect the privacy of the victim and has a precedent in the similar handling of psychiatric records. Surveys of SAVs have identified that they desire information about sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), pregnancy, emergency contraception, follow-up care, and physical and psychological health effects of sexual assault.51 Connecting the SAV to outside resources is critically important to care.52,53

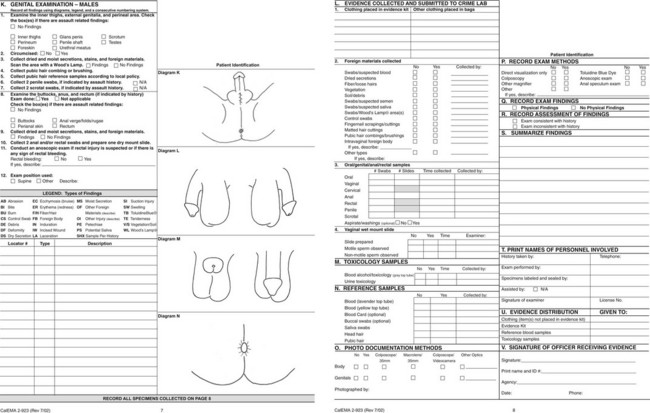

Providing written information on these topics to the patient and getting his or her signature in confirmation documents the patient’s receipt of follow-up recommendations. Before the history taking is begun, the SAV’s immediate privacy and personal needs should be addressed. Box 67-2 outlines some of the issues that may make the interview more comfortable for the patient and ensure receipt of reliable historical information from the patient. The group taking the history may include a law enforcement officer, patient advocate, medical assistant, and FE. A detailed history is important. California was the first state to mandate a uniform examination protocol and specific training for examiners (Fig. 67-2).54

Figure 67-2 Forensic Medical Report: Acute (<72 hours) Adult/Adolescent Sexual Assault CalEMA 2-923 from the State of California Emergency Management Agency. This form is available at http://www.calema.ca.gov/PublicSafetyandVictimServices/Documents/Forms%202011/Medical%20forms/Acute%20Adult%202-923.pdf. Accessed January 20, 2013.

History of Type of Sexual Assault

Questions about sexual acts need to be explicit and phrased in terms understandable to the SAV. Unless specifically asked, many victims will not disclose that injuries are a result of the assault.19 Language used by the SAV to describe sexual acts should be documented in the medical record. It is important for the FE to ascertain whether the victim voiced her lack of consent and whether that terminated the behavior. The victim’s own words should be used as often as possible and recorded in quotation marks to preserve the integrity of the interview; if the police record the interview, it may not be transcribed until weeks or months later. The experienced FE also gathers information about the sequence and type of sexual acts that occurred during an assault, including not only kissing, fondling, use of foreign objects, and digital manipulation, but also fetishism, voyeurism, or exhibitionism on the part of the suspect. Table 67-1 lists additional information, which may be useful for the investigation.

Table 67-1

Useful Information Not Routinely Found on the Sexual Assault Forms

| Positions used during the assault | Affects the location of injury |

| Positions used during the examination | Helps to orient pictures |

| Sexual dysfunction in the suspect | Associated with increased violence and anal attack |

| Repeated thrusting by suspect | May explain loss of seminal product |

| Victim assistance with insertion of penis | May explain lack of genital injury |

| Did penis remain in vagina after ejaculation? | May explain loss of seminal product |

| How do you know ejaculation occurred? | Helps determine where semen may be found |

| Prior sexual experience | Lack of sexual experience associated with increased hymenal trauma |

| Gravity and parity | May be a factor in genital injury |

| History of prior victimization | At increased risk for post-traumatic stress disorder; need triage for counseling |

| Mental health history, sex trade worker, previous incarceration, homeless, history of substance abuse | Increased severity of attack, worsening mental health problems, increased risk of revictimization, worsening drug use |

| Past medical history | May explain physical or laboratory findings |

| Sexual arousal and response | Need to assuage guilt, understand prevalence; may alter physical findings |

Use of Recording Devices by Suspect or Bystanders

The ubiquitous nature of recording devices means that an important, early question to ask of the victim is whether such devices were used by the suspect or bystanders; this may provide evidence of the assault.55

Drug and Alcohol Use

Inquiry about drug and alcohol usage is important and necessary.56–58 Like driving under the influence, a sexual assault may be the first indicator that the victim has a drug or alcohol problem.59 Recent data indicate that drug and alcohol abuse by the victim is associated with a concurrent increased risk of an additional assault in the next 2 years; assaulted drug users are at risk for an escalation of drug abuse after the assault60 and self-blame.61 These victims need prompt referral for counseling and drug rehabilitation programs, a service frequently overlooked by forensic teams.62 Furthermore, the use of drugs and alcohol are relevant to issues of consent, credibility, and corroboration.63,64 In the past, studies have not found a correlation between substance use and injury,65 but recent studies indicate an increase in nongenital26,43 and anogenital.33 trauma. The FE should order drug screening if the victim reports loss of consciousness or forced ingestion, appears confused, is amnesic, or has other changes in physical or vital signs that are suspicious for drug use.55 National drug screening data from SAVs show that the prevalence of drug use is higher among SAVs than the general population.66,67 Moreover, drugs are frequently used in combination. The two most popular combinations are alcohol and marijuana, followed by alcohol and benzodiazepines.68 Routine surveillance for drugs and alcohol is recommended because self-reporting is inaccurate69 and drug-facilitated sexual assault appears to be increasing worldwide.70,71 Screening should include blood, urine, and, with newer technology, samples of head hair.72 Special policies and procedures need to be developed for SAVs who are incapacitated or are otherwise incapable of giving consent.73,74 One should not forget to inquire whether the suspect used drugs or alcohol. Perpetrators who use drugs and alcohol are less likely to use condoms, and on apprehension, drug testing will be needed to confirm this information and should be routine.

History of Child Abuse

A history of childhood abuse increases the risk of repeat assault. Researchers now believe that identification of this vulnerable group is a prerequisite for prevention. The sexual assault examination may be the one time during which the question of prior abuse is raised; a positive answer provides additional justification for referral for psychological services.29

Mental Illness

About a quarter of the victims requiring sexual assault evaluation will have mental health problems. A history of mental illness has been shown to increase the severity of the sexual and physical attack. Moreover, the sexual assault often results in an exacerbation of the mental illness and a higher rate of post-traumatic stress disorder.75 Similar vulnerabilities accrue to sex trade workers and to women with a history of previous incarceration, current or past substance abuse, or homelessness.29

Prior Sexual Experience

Knowledge about the victim’s prior sexual experience is pertinent. New information has emerged that women without sexual experience are more likely to sustain genital trauma and specifically more likely to have hymenal tearing.76 Because hymenal and vaginal tears are usually associated with the dramatic presentation of bleeding, it is incumbent on the examiner to ascertain the source of hemorrhage. The lack of visible genital injury in the female who has not had prior sexual experience does not exclude the possibility of intercourse.

Methods of Controlling the Victim

Much can be gleaned about the suspect from a careful interview of the SAV. Areas of interest for the examiner include the methods of approach and control of the SAV, the offender’s reaction to resistance by the victim, and the occurrence of sexual dysfunction in the suspect. Although the approach to the victim is usually easy to obtain, understanding how the suspect controlled the victim may not be immediately clear, as the mere presence of the suspect may be perceived by the victim as a threat to life and may result in control of the victim’s actions. Most protocols inquire about verbal threats and weapons, but getting the exact context of these (verbatim if possible) and determining whether the threats were carried out are important. Few assaults are silent; one should inquire about demands, reassurance, compliments, questions, concern, or apologies by the perpetrator. Similarly, if a weapon was used, notation should be made regarding whether the victim saw the weapon or whether it remained a verbal threat only. Was it a weapon of choice (brought with the suspect) or one of opportunity? Did the suspect relinquish it at any time or use it? The examiner should inquire into the amount and timing of the force used by the assailant along with the use of any derogatory or profane language. The examiner should inquire about strangulation; SAVs typically do not volunteer this information. Strangulation tends to occur late in abusive relationships and has been associated with a higher risk for major morbidity and mortality.77,78 The FE should take special care to ask questions in a manner that does not imply that the victim should have done something to protect herself or to prevent the occurrence of the sexual assault. In some cases, resistance may provoke an alternative demand, compromise, negotiation, and threat of force or use of force. If force is threatened, the examiner should be clear about whether it was used and understand how much and how long it was applied. If a change of demeanor occurred, the FE should know what caused it and what was the change.79

Sexual Dysfunction in Offenders

Nearly 34% of convicted rapists have a sexual dysfunction, and this information is obtainable from the SAV. Sexual dysfunction includes impotence, premature ejaculation, retarded ejaculation, or conditioned ejaculation (Box 67-3). This knowledge improves the examiner’s ability to understand and collect the evidence. A premature ejaculator may have left semen on clothing or in the environment rather than intravaginally. Retarded ejaculation is associated with multiple sex acts, including anal intercourse, and a more violent attack, involving both genital and nongenital trauma.39,80 Serial rapists have been identified based on language and demand for a specific order of sexual acts from several SAVs. In addition, the SAV can be asked about any unique lesions or pathology of the perpetrator’s genitalia or other identifying characteristics.81

Use of Foreign Object

Penetration with a foreign object is associated with greater violence and an increased prevalence of genital and nongenital trauma, stranger assault, and multiple assailants.33,37 The FE should understand that the definition of a foreign object on the forensic medical form is not the same as the legal definition. The legal definition of foreign object is any substance, instrument, or device, including any body part other than a sexual organ.82

Methods Used by the Offender to Avoid Detection

The FE should inquire about the methods used to avoid detection and facilitate escape, such as wearing masks or gloves, blindfolding the victim, or disabling the phone. An experienced assailant may also attempt to destroy evidence, such as forcing the victim to shower. Lastly, the FE should ask about missing items. Valuables or personal items retained as souvenirs have evidentiary value. The FE should ask the victim if the assailant is known to him or her; even if the assailant is unknown, the victim may have a wealth of information about characteristics and behavior of the assailant.41

Performing the Physical Examination and Evidence Collection

The physical examination should be meticulous and include the collection of trace evidence and reference standards (see Fig. 67-2). There is a positive association between SAV injury and the filing of charges, successful prosecution, and sentencing.5,83 In general, the sequence of observation, photography in situ, collection of evidence, and written documentation should be followed (Box 67-4). All items should be dry and placed in paper containers (plastic is not used because it inhibits drying and degrades biologic evidence) that are labeled (Box 67-5) and sealed. Each container should be sealed securely with tape, and the examiner should initial or sign across the tape and onto the container or bag. For the integrity of the evidence to be preserved, the SAV should not be left alone in the room with it, and the FE should wear powder-free gloves to prevent contamination of the evidence. If the evidence is stored, a locked unit should be available. Methods for preserving the chain of custody, a fundamental principle in the criminal justice system, should be understood by all personnel (Box 67-6). A complete examination and historically relevant evidence collection should be performed, irrespective of the time between assault and examination. One investigator documents the retrieval of salivary DNA from a bite mark on a body even after the body had been submerged in water for more than 5 hours.84 The FE should not second-guess what the laboratory may or may not recover based on rigid time frames. If there is a history of loss of consciousness or significant memory impairment, then all specimens should be collected.

Examination of the Skin

The FE needs to describe the SAV’s demeanor and general appearance. The examiner should be especially careful to use specific terms and note responsiveness and ability to cooperate and give a history. All clothing worn during the assault should be inspected, collected, and photographed. A Wood’s lamp or ALS should be used to detect dried secretions and to document the findings (Box 67-7).

When the SAV is undressed, the FE uses the Wood’s lamp or ALS over the body and documents positive fluorescence. Dried secretions should be removed with a cotton swab moistened with sterile, distilled water. If one side of the swab is flattened and only that side is used to collect the specimen, the material is effectively concentrated. Conversely, wet secretions should be taken in the same manner with a dry swab. Swabs should be taken from areas of contact indicated by the SAV, even if there is no fluorescence or crusting seen. A double-swab technique is used to collect saliva from skin (Box 67-8).85 Bite marks need special attention (Box 67-9).86 Control swabs should be taken in areas adjacent to the material removed and labeled as such. All swabs should be dried in a stream of cool air at least 60 minutes before packaging. Swab-drying machines are available with locks to facilitate this process. To prevent contamination, only one person’s evidence should be in the dryer at a time, and the drying chamber should be cleaned after each use with a solution of 10% household bleach. The location of all foreign material should be documented on the body diagrams and packaged in the standard fashion. Fingernail clippings or scrapings should be collected according to local custom and only if there is historical relevancy. All preexisting injuries and acute trauma need to be documented in the report.

Diagrams of the body should be large enough to allow documentation to remain clear. If need be, copies of the state and local diagrams should be available in full-page format to accomplish this. The documentation process in some states is artistic, which means the FE draws the injury on the diagram. California has switched to a purely descriptive approach for uniformity and clarity (see Fig. 67-2).

Head, Neck, and Oral Cavity

In examining the head, neck, and oral cavity, special attention should be given to the integrity of the frenula, buccal surfaces, gums, and soft palate. The SAV should not be allowed to eat or drink before this examination. If the SAV gives a history of oral copulation with ejaculation, then the upper and lower lips should be wiped with two moistened swabs. Next, the examiner should swab from the gum to the tonsillar fossae, the upper first and second molars, behind the incisors, and in the fold of the cheek. If more than one swab is used to swab these areas, each should be labeled appropriately. Last, with a 16-inch piece of unwaxed floss, with two knots tied about 2 to 3 inches apart in the center of the floss, the SAV should floss her teeth, using only the section between the knots. While flossing, the patient should lean over a clean 8 × 10-inch piece of paper to catch any debris. The paper and floss are dried and bundled together. If the SAV is unable to use the floss, the examiner, wearing gloves and goggles, can perform this procedure.87

Hair matted with secretions or debris should be cut out and packaged. Additional hair might also be needed for drug analysis depending on the laboratory.72 Signs of manual or ligature strangulation may include neck injuries with petechiae of the skin and conjunctiva. Reference samples for head hair and saliva should be taken according to local custom, including buccal swabs made for DNA analysis. Reference standards are used to determine whether the evidence specimens are of victim origin or are foreign. In addition, they may help identify or eliminate potential suspects.

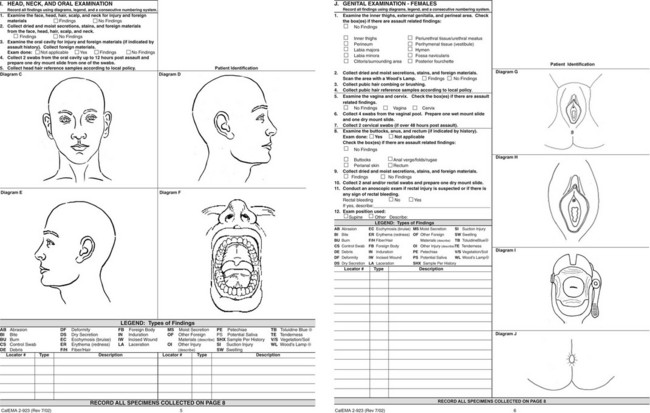

Anogenital Examination

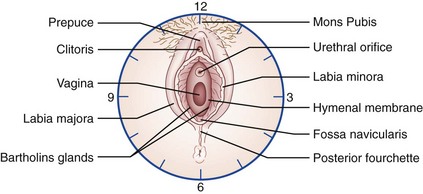

The anogenital examination should begin with gross visualization of the inner thighs, external genitalia, and perineal area and anus, followed by Wood’s lamp or ALS visualization of the area to identify secretions. All trauma, secretions, and foreign material should be noted and appropriately handled. Gross visualization yields positive findings in 20 to 30% of cases (range 5-65%).4,6,34,42,76 Genital trauma associated with sexual assault is considered to be a mounting injury because it occurs at the point of first contact of penis to vagina. This area, the posterior fourchette (soft tissue) or the perineal body (the juncture of the tendons of the superficial transverse perineal and the bulbocavernosus muscles), is inherently weak, and continued pressure will result in tearing.24,88 The position of restraint, male straddling female, will also effectively prevent the victim from accommodating the erect penis. The angle of the erect penis is not the same as the angle the vagina makes with the vestibule (approximately 45 degrees). Moreover, the vagina is considered a potential space. The lateral walls are more rigid than the anterior and posterior walls so that in its normal state, the anterior wall is collapsed onto the posterior wall; hence the need for a speculum to lift the anterior wall during the gynecologic examination.89 During voluntary intercourse, the changes that occur with sexual stimulation, the human sexual response, remove these normal anatomic barriers, and the female voluntarily tilts her pelvis.90,91 Sexual arousal and orgasm are now understood to be a reflex of the autonomic nervous system requiring an intact sacral arc.92,93 It is hypothesized that this response can be either facilitated or inhibited by cerebral input. It can occur in both males and females even when it is not wanted or the victim is unconscious. In women, vaginal wetness can occur subconsciously and is thought to be a protective mechanism. Some perpetrators have taunted victims about its occurrence, further increasing the shame and guilt of the victim. The FE should inquire and reassure the SAV that this reaction is neither abnormal nor evidence of consent. Approximately 4% of SAVs experience this phenomenon, although this is probably a gross underestimate as a result of embarrassment94,95 and lack of inquiry. The FE should not conflate sexual response, consent, and injury; genital injury is not an ineluctable consequence of sexual assault. Currently, there is still no finding or group of findings that can differentiate consensual from nonconsensual sex, and more research is underway.96,97

Typically, genital injury is located posteriorly among the 3, 6, and 9 o’clock positions (Fig. 67-3), with the posterior fourchette being the most common site of injury.23,32,34,39 Findings are the sequelae of blunt force trauma that produces tears, ecchymosis, abrasions, redness, and swelling. The last two may be difficult to recognize without a follow-up examination, and some investigators have suggested that redness or swelling not be reported if a second examination is not performed.23 Hymenal trauma is not the most common site of injury, as myth would have it. Hymenal trauma is more common in adolescents and those without sexual experience.23,76 Genital injury has consistent topologic features, now well documented in the literature; this pattern is consistent with an entry injury, occurring with insertion or attempts at insertion of the penis into the vagina.

Many factors affect the prevalence of genital injury, and the FE should be familiar with them (Box 67-10). Colposcopic magnification should be used to photographically document these areas and to better identify the type of trauma seen. Colposcopy has been the preferred and best method for determining genital injury.98,99 Currently, many centers are using digital photography and videography with excellent results and less cost. Certain environmental factors have been identified with colposcopically recognized genital changes; this is particularly true with intravaginal findings (Table 67-2).100 Frequently, trace evidence is seen only with the colposcope. We use adhesive note paper (Post-it notes) to capture such tiny particles while visualized under the scope. The Post-it is then folded and inserted into an envelope. Examiners should check with their local crime laboratory to see if this method is acceptable. Pubic hair brushings are collected by placing a sheet of paper under the patient’s buttocks and brushing the pubic hair downward. The paper and brush should be bundled together and packaged. A pubic hair standard may be obtained according to local forensic procedures.

Table 67-2

| FACTOR | FINDINGS |

| Smoking | Edema, erythema, petechiae, abrasion |

| Tampon use at the time of examination | Erythema, petechiae, abrasion |

| Speculum manipulation | Laceration |

| Consenting intercourse | Erythema, petechiae, abrasion, ecchymosis |

| Herpetic infection | Microulcerations |

A warm speculum moistened with water should then be inserted into the vagina. Inspection of the vagina and cervix should be performed first grossly, then with colposcopic photography. If the SAV reports bleeding, the source needs to be determined. Bleeding is commonly associated with hymenal, vaginal, or combined tears. In contrast, menstrual bleeding at the time of an assault has been shown to decrease physical findings.101 Swabs from the vagina and cervix should be obtained, air-dried for 60 minutes, and packaged. Cervical specimens augment those from the vaginal pool because the cervix acts as a reservoir and provides evidence of seminal products for longer periods of time (Table 67-3).102 The examiner should inspect the cervix carefully for injury, including patterns. Injury, seen in about 10% of cases, is related to penile, digital, or foreign object penetration, but ectropion, cervicitis, or hyperplasia can be confused with trauma and make the cervix more vulnerable to injury; a follow-up examination is necessary to prevent misdiagnosis.103 To check for motile sperm, the FE should inspect a wet mount slide. This method is useful because it gives a time frame for the assault, and sufficient numbers of sperm (60-100) allow for DNA identification of a suspect. Semen is found about 50% of the time. The FE should communicate this information to the investigator as soon as possible. The wet mount slide is then dried and prepared for deposit into the rape kit. Aside from time and site of deposition,104–106 female and male factors influence the ability to find semen (Table 67-4). Not all cases result in the deposition of semen. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is a sensitive and specific commercially available probe for detection of the Y chromosome in epithelial cells up to 7 days after penetration, ejaculation, or saliva deposition.107 Typically, a bimanual examination is not performed.

Table 67-3

Maximum Reported Time Intervals for Sperm Recovery

| BODY CAVITY | MOTILE SPERM | NONMOTILE SPERM |

| Vagina | 6-28 hr | 14 hr-10 days |

| Cervix | 3-7 days | 7.5-19 days |

| Mouth | — | 2-31 hr |

| Rectum | — | 4-113 hr |

| Anus | — | 2-44 hr |

Table 67-4

Factors Influencing Loss of Sperm and Seminal Fluid

| FEMALE FACTORS | MALE FACTORS |

| Prior trauma to birth canal | Condom use |

| Lost on withdrawal of penis | Vasectomy |

| Vaginal hygiene (e.g., douching, wiping) | Azoospermia |

| Repeated penile thrusting | Drug and alcohol abuse |

| Penis remains in the vagina after coitus | Sexual dysfunction |

| Change of posture | Failure to ejaculate |

Special Staining Techniques

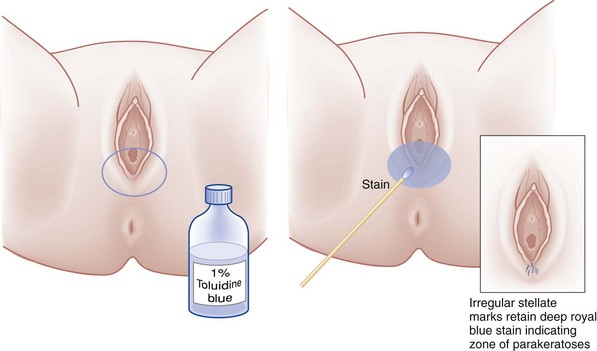

The use of special staining and lubrication techniques should be reserved until all photography has been completed and all specimens have been collected. On areas that are painful, 2% lidocaine gel can be used to obtain better visualization and pictures. Toluidine blue dye is a nuclear stain that has been shown to enhance gross visualization of external genital (vulvar) injuries (Fig. 67-4). Toluidine blue dye has some spermicidal activity108 but was shown in one small study not to influence DNA analysis.109 Stain results depend on the presence or absence of a nucleated cell population at the exposed surface. Positive stain results can be seen with trauma, cancer, and areas of inflammation with a nucleated cellular infiltrate. Acutely, with tissue swelling and transudation, the dye may lift off quickly. Twenty-three categories of benign disease, along with columnar epithelium, and mucus will take up this stain. Toluidine blue dye is nonspecific; it does not replace a clear photograph of the injury and should be used only to enhance trauma seen with the colposcope or as an adjunct for gross visualization. It should not be used to date injuries or on the deceased because postmortem artifact can take up the dye. Diffuse staining or patchy uptake should not be reported.110 Uptake should not be reported when no findings are seen with colposcopy.99

Photographic Documentation

Photographic documentation has become the standard of care. It eliminates the problem of hyperbole and understatement in the FE’s description and allows the court to see a visual representation of findings on examination. It is important to note that photographic documentation makes each case available for diagnosis, research, peer review, and consultation, alleviating the need for repeated examinations by defense experts.111,112 The entire examination should be photographically documented if at all possible, not just the positive findings. All photographs should be correctly labeled to show patient identification, date, time, and examiner. Frequently this information can be combined with a color guide and ruler. Jurors usually want to know how pictures are identified. The FE should develop a standard photographic technique, making certain that the plane of the film is parallel with the injury to minimize distortion. Photographs of skin are enhanced if the background is blue or green because the automatic lens adjusts according to the lightest part of the photograph. The examiner should take photographs of lesions first without magnification, then take closer views as needed. The full extent of the injury needs to be captured. Use of magnification usually necessitates more than one shot. The examiner should take many photographs because he or she has this opportunity only once (Box 67-11 outlines tips for performing photographic documentation in sexual assault cases). Photographs are also a concern for SAVs. Most SAVs worry about where the photographs are kept and whether their name will appear on the photographs. Keeping the SART record separate from the medical record is reassuring. Some groups go a step further and separate the photographs from the written reports.

Sexually Transmitted Diseases and Pregnancy

The risk of acquiring an STD after a sexual assault is small but will vary by region and number of assailants (Table 67-5). Testing for STDs is expensive, requires a reassessment of the patient, which is often difficult, and has no forensic value. Most protocols no longer require or pay for this type of assessment. In addition, many SAVs have preexisting STDs. Most providers prefer preventive therapy (Box 67-12), and it offers the SAV the psychological benefit of immediate protection from infection. For updated information and alternative therapies for patients who are pregnant or have specific allergies, the physician can consult www.cdc.gov and search for “std treatment.” FEs should also consult their state health departments for possible drug and dosage changes necessitated by local susceptibilities of these organisms. The efficacy of these regimens in preventing gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, bacterial vaginosis (BV), and Chlamydia trachomatis genitourinary infections after sexual assault has not been evaluated. If vaginal discharge, malodor, or itching is present, the wet mount slide should also be examined for BV and candidiasis. The FE should counsel patients about the possible toxicity of any regimen; gastrointestinal problems are especially common, and the FE should consider antiemetic medication, particularly if emergency contraception is also prescribed. All patients should be advised to abstain from alcohol for 24 hours after metronidazole use and from sexual intercourse until the treatment is completed.113

Table 67-5

Risk of Sexually Transmitted Disease after Sexual Assault

| Gonorrhea | 6-18% |

| Chlamydia | 4-17% |

| Syphilis | 0.5-3% |

| HIV infection | <1% |

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B vaccination, without hepatitis B immune globulin, is recommended for SAVs who are unimmunized (Box 67-13). Risk factors for hepatitis B virus include multiple sexual partners (more than one sex partner in a 6-month period), a recent history of an STD, men who have sex with men, correctional facility inmates, and intravenous drug users. Currently, testing to determine antibody levels in immunocompetent persons is not necessary because most fully vaccinated persons have long-lasting protection, and relatively high rates of protection are achieved after each vaccine dose. The FE should give the vaccination even if the completion of the series is not assured.113 In some protocols, this cost may not be covered.

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

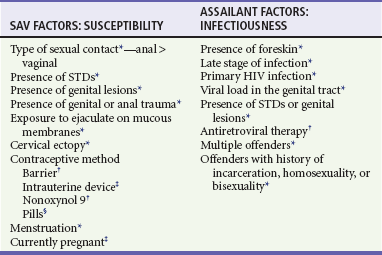

Although human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) exposure is of great concern to SAVs, the risk of seroconversion is low. The risk of HIV transmission from an HIV-positive male is 0.1 to 2% for consensual vaginal intercourse and 0.5 to 3% for receptive rectal intercourse, with transmission rates from oral sex substantially lower. The FE needs to be familiar with the local epidemiology of HIV and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; state guidelines for postexposure prophylaxis for SAVs, if any; the nature of the assault; and any HIV risk behaviors exhibited by the assailant, such as high-risk sexual practices or injection drug or crack cocaine use. Specific circumstances affecting the SAV and assailant, if known, can increase the probability of transmission (Table 67-6). The rate of HIV transmission in sexual assault is likely to be higher than in consensual intercourse because of the possible presence of genital trauma. The effectiveness of postexposure prophylaxis is based solely on the treatment results of health care workers who have had occupational exposure, and these data have been extrapolated to SAVs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that therapy be considered in cases in which the risk for HIV is likely high and that all such cases be referred for consultation with an HIV specialist. Costs may not be covered under local protocols, and postexposure prophylaxis needs to be provided in the context of a comprehensive counseling, treatment, and follow-up program. To maximize the likelihood of success, therapy should be initiated as soon as possible or up to 72 hours after the assault, so expeditious referral is prudent.113

Pregnancy Prophylaxis

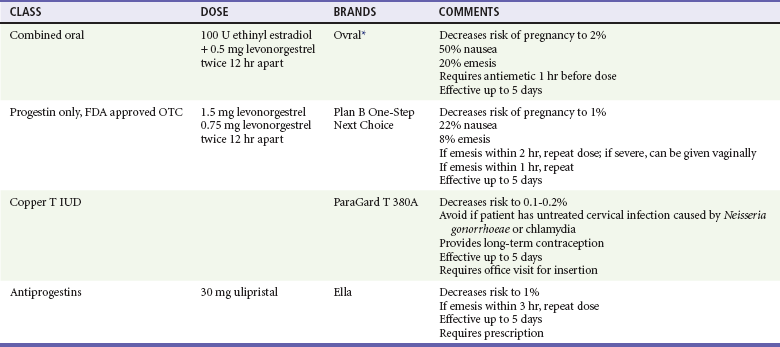

There is a 2 to 4% risk of pregnancy from random unprotected intercourse; this figure reaches nearly 50% in women 19 to 26 years old, who are at their most fertile period, when combined with midcycle exposure. The immediate use of an emergency contraceptive (EC) can reduce the risk of pregnancy to 1 to 2%. Its effectiveness depends on the regimen used and the time interval between exposure and treatment (Table 67-7). Data show that an EC should be offered up to 5 days after unprotected sex. There are no absolute contraindications to the use of hormonal EC, even for women who have contraindications to the long-term use of combination hormonal contraception. In those who have active migraine headaches with neurologic symptoms or a history of stroke, pulmonary embolus, or deep vein thrombosis, progestin-only EC or the insertion of an intrauterine device (IUD) should be considered first. The IUD offers the advantage of up to 10 years (depending on the device) of effective contraception. Evidence suggests that there is not an increase in ectopic pregnancy with EC use. Although there are no studies large enough to quantify the teratogenicity of hormonal ECs, no increase in birth defects has been detected in infants exposed in utero to daily oral contraceptive use. Pregnancy testing is not necessary before hormonal EC.114,115

Table 67-7

Types of Emergency Contraception

FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; IUD, intrauterine device; OTC, over the counter.

*Other hormonal contraceptives that are useful to make up this combination can be found at www.not-2-late.com.

As of June 2011, 17 states and the District of Columbia require hospital EDs to provide EC-related services to SAVs, and 12 states plus the District of Columbia require hospitals to dispense EC on request. Despite legal efforts and practice recommendations from the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP),116 the American Medical Association (AMA),117 the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP),118 and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG),119 EC remains underused, and patients are not informed about its availability.120,121

Debriefing

Regardless of any physical injury, psychological distress is typically present after sexual assault, and the FE needs to acknowledge that from the beginning of the examination. Establishing a quiet and calm place for the examination and evidence collection reassures the SAV and gives back to her a sense of control and safety. At the termination of the examination, the FE should spend time reviewing the physical and genital injuries and address modes of therapy as appropriate. The examiner should discuss any pending laboratory data and how results will be communicated (by phone, written, or both) with the SAV. The method of communication should be acceptable to the SAV. The examiner should review all medication and vaccinations (e.g., tetanus), discuss side effects, and provide contact phone numbers in case of problems or questions. The examiner should review the common psychological problems (Box 67-14) and reinforce the need for counseling. The advocate who has been present during the examination can be a personal contact already established with the SAV. Nonetheless, contact numbers for rape crisis services, local crisis intervention, social services, drug and alcohol services, HIV services, and emergency psychiatric services should be reviewed in detail, and all referrals should be discussed before departure (Box 67-15). Compensation for victims of crime should be discussed and appropriate referrals made.

A forensic follow-up examination of all patients should be scheduled. This examination is particularly important for SAVs with genital injury. It documents the healing of injury and differentiates findings that can be confused with trauma, such as hypervascularity, telangiectasis, and cherry red spots.39,103,111 Its utility extends to nonspecific injuries such as swelling or redness, which are difficult to detect and create frequent interobserver disagreements.23 This examination also gives the FE an opportunity to review any problems, encourage counseling if it has not already begun, and connect the SAV to outside resources. One should do drug and alcohol counseling when appropriate. All of these plans should be in written format. For the SAV’s needs to be met and for adverse medical or psychological outcomes to be prevented, follow-up is critical.21,30,52,53

Elderly Victims

Two percent to 6% of all SAVs are older than 50 years. The risk of being sexually assaulted or physically assaulted is further increased for homeless women in this age group.29,122 Older women are less likely to report sex crimes because of self-blame and humiliation. The asexual stereotype attributed to them by family, caretakers, and other professionals often prevents detection.123 Whereas most elderly SAVs are seen within 72 hours, delayed reporting also occurs. This is especially true when the perpetrator is a caregiver.124–126 In 2005, A Perfect Cause, advocates for disability and elder rights, documented that 795 registered sex offenders were living in long-term care facilities and five were employees.127 Elder SAVs present unique challenges to the FE. The history should be expanded to include medical problems, medications, surgical procedures, history of dementia, and neurologic problems. Obtaining the history may be difficult. Some patients may be in a disorganized state without a diagnosis of dementia. Others may have hearing impairment, cognitive disabilities, or psychiatric disturbances; these conditions, considered important vulnerabilities, often require special interviewing skills, and the examiner may need to obtain the history from other reliable sources.128 Positioning should be thoughtfully performed with regard to limitation of motion for both natural and artificial joints and the need to prevent cardiovascular problems that attend anxiety and stress in this frail population. Skin changes related to aging, infection, and trauma can be difficult to discern, and a follow-up examination, including photographic documentation, will help to resolve these important issues.129 Bruising not may be seen initially.130

Usually, the SAV lives alone and the assault occurs at her home; the assailant is almost always a stranger. Among those abused in facilities, the suspect is most often an employee or a resident. Sexual dysfunction, substance use, and a history of prior sexual assault or other criminal behavior are commonly seen in these perpetrators; robbery is often involved, and female assailants are not infrequent. The most common type of assault is penile-vaginal contact, and genital injury is more frequent and severe than in younger SAVs, necessitating hospitalization and even surgery. The localized pattern and type of physical injuries are similar to those seen in younger victims.131 Physical restraint is common and usually in excess of what is required for control.132 The aftermath of assault is particularly devastating for this age group. Older adults have high morbidity and mortality rates, even when they have sustained relatively minor injury; this may be attributed to concurrent medical conditions, decreased physiologic reserve, or adverse reactions to and between medications. Psychologically, post-traumatic stress with subsequent illness is more frequent and severe and leads to diminished functional capacity; this is devastating to this population, in which resources and support are limited.

Sexual abuse is the most under-reported form of elder abuse. A meaningful program addressing elderly SAVs should involve education and participation of adult protective services, in-home health care or nursing home providers, and other agencies representing the elderly or disabled, along with SART. Policies and procedures addressing elderly patients unable to give consent should be in place and in accordance with state laws.133

Male Victims

Male sexual assault is vastly under-reported. Overall, male rape accounts for 8% of all noninstitutional U.S. rapes.134 Certain special populations appear to be at increased risk for sexual assault: gay and bisexual men, veterans, prison inmates, and men from physical and mental health treatment facilities.135 Most victims seen come from institutional settings, with very few indeed from the nonincarcerated population. Factors that act as barriers to reporting this crime include societal beliefs that a man can defend himself and fear that his sexual orientation is suspect. The need to maintain emotional control makes disclosure very stressful. Men need to be accorded the same sensitivity and support as their female counterparts, yet most mental health centers neither have the male staff or volunteers nor offer full services for male SAVs.136 This is particularly troubling because depression and suicidal ideation are significantly associated with male sexual assault.134

Except for their anatomic differences, the procedures for the history, physical examination, evidence collection, and medical treatment are the same. Certainly, because of the typical location of injuries, some researchers have emphasized the increased risk of exposure to HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C.137 Some notable differences in the assault characteristics from those seen in female victims include a predilection for anal and oral sexual contact, with subsequent injury seen in 50 to 67%, more common use of the prone position during the assault, a higher incidence of nongenital trauma (80% in one study), use of a weapon, assault by a stranger or multiple assailants, and a history of abduction. Injuries to the penis and scrotum occur less often and may be the result of a nonsexually related injury (e.g., kicks).138 In one study the use of colposcopy, in addition to anoscopy, allowed the discovery of increased physical examination findings in men. As with female SAVs, colposcopy is recommended because of its additional utility for photodocumentation and collection of trace evidence.139

A different picture emerges from survey data taken from the community setting. Male SAVs reported no physical injury, penetration, weapon use, or substance use. The vast majority did not report to police or seek medical or mental health assistance. It is important to note that of those who did seek care, most did not reveal the actual reason for the visit.136,140

References

1. Basile, KC, Saltzman, LE, Sexual violence surveillance: uniform definitions and recommended data elements. Atlanta:National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2002. http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pub/sv_surveillance.html.

2. Office on Violence Against Women, A national protocol for sexual assault medical forensic examinations. 2004. http://www.ovw.usdoj.gov/publications.html.

3. Green, W, Panacek, E. Sexual assault forensic examinations in evolution. J Emerg Med. 2003;25:97–99.

4. Stene, L, Ormstad, K, Schei, B. Implementation of medical examination and forensic analyses in the investigation of sexual assaults against adult women: A retrospective study of police files and medical journals. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;199:79–84.

5. Campbell, R, Patterson, D, Lichty, L. The effectiveness of sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) programs. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2005;6:313–329.

6. Gilles, C, Van Loo, C, Rozenberg, S. Audit on the management of complainants of sexual assault at an emergency department. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;151:185–189.

7. Saltzman, L, et al. National estimates of sexual violence treated in the emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:210–217.

8. Ledray, L, Kraft, J. Evidentiary examination without a police report: Should it be done? Are delayed reporters and nonreporters unique? J Emerg Nursing. 2001;27:396–400.

9. Garcia, S, Henderson, M. Blind reporting of sexual violence. FBI Law Enforc Bull. 1999;68:13–16.

10. Boyko, EJ, et al, U.S. Department of Defense. Military services sexual assault report CY 2006. DoDSAPa Response. Washington, DC:U.S. Department of Defense; 2010.

11. Price, B. Receiving a forensic medical exam without participating in the criminal justice process: What will it mean? J Forensic Nurs. 2010;6:74–87.

12. Campbell, P, Greeson, M, Patterson, D. Defining the boundaries: How sexual assault nurse examiners (SANEs) balance patient care and law enforcement collaboration. J Forensic Nurs. 2011;7:17–26.

13. Campbell, P, et al. A Systems Change Analysis of SANE Programs: Identifying Mediating Mechanism of Criminal Justice System Impact. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice; 2009.

14. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Injury Prevention and Control: Data and Statistics (WISQARS). Atlanta, Ga:CDC; 2011. www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html.

15. Tjaden, P, Thhoennes, N, Extent, Nature, and Consequences of Rape Victimization: Findings from the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC:U.S. Department of Justice; 2006. www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/210346.pdf.

16. Jones, J, Alexander, C, Wynn, B, Rossmani, L, Dunnuck, C. Why women don’t report sexual assault to the police: The influence of psychosocial variables and traumatic injury. J Emerg Med. 2009;36:417–424.

17. McCall-Hosenfeld, JL, Freund, KM, Liebschutx, JM. Factors associated with sexual assault and time to presentation. Prev Med. 2009;48:593–595.

18. Campbell, J. Lethality assessment approaches: Reflections on their use and ways forward. Violence Against Women. 2005;11:1206–1213.

19. Biroscak, B, Smith, P, Roznowski, H, Tucker, J, Carlson, G. Intimate partner violence against women: Findings from one state’s ED surveillance system. J Emerg Nurs. 2006;32:12–16.

20. Rennison, C. Rape and sexual assault: Reporting to the police and medical attention, 1992-2000. In: Bureau of Justice Statistics Selected Findings. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice; 2002.

21. Anderson, T, Guajardo, J, Luthra, R, Edwards, K. Effects of clinician assisted emotional disclosure for sexual assault survivors: A pilot study. J Interpers Violence. 2010;25:1113–1131.

22. Poirier, M. Care of the female adolescent rape victim. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:53.

23. Adams, J, Girardin, B, Faugno, D. Adolescent sexual assault: Documentation of acute injuries using photo-colposcopy. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2001;14:175–180.

24. Jones, J, Rossman, L, Hartman, M, Alexander, C. Anogenital injuries in adolescents after consensual sexual intercourse. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:1378–1383.

25. Stermac, L, Du Mont, J, Kalemba, V. Comparison of sexual assaults by strangers and known assailants in an urban population of women. CMAJ. 1995;153:1089–1094.

26. Sugar, NF, Fine, DN, Eckert, LO. Physical injury after sexual assault: Findings of a large case series. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:71–76.

27. Jones, J. Comparison of sexual assaults by strangers versus known assailants in a community-based population. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:454–459.

28. Ullman, SE, Najdowski, CJ. Understanding alcohol-related sexual assaults: Characteristics and consequences. Violence Vict. 2010;25:29–44.

29. Hudson, A, et al. Correlates of adult assault among homeless women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:1250–1262.

30. Boykins, A, et al. Minority women victims of recent sexual violence: Disparities in recent incident history. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19:453–461.

31. Marsh, M, Purdin, S, Navani, S. Addressing sexual violence in humanitarian emergences. Glob. Public Health. 2006;1:133–146.

32. Jones, J, Rossman, L, Wynn, B, Dunnuck, C, Schwartz, N. Comparative analysis of adult versus adolescent sexual assault: Epidemiology and patterns of anogenital injury. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:872–877.

33. Drocton, P, Sachs, C, Chu, L, Wheeler, M. Validation set correlates of anogenital injury after sexual assault. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:231–238.

34. Riggs, N, Hourym, D, Long, G. Analysis of 1, 076 cases of sexual assault. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;34:358–362.

35. Eckert, LO, Sugar, N, Fine, D. Factors impacting injury documentation after sexual assault: Role of the examiner experience and gender. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1739–1746.

36. Grossin, C, et al. Analysis of 418 cases of sexual assault. Forensic Sci Int. 2003;131:125–130.

37. Sturgiss, EA, Tyson, A, Parekh, V. Characteristics of sexual assaults in which adult victims report penetration by a foreign object. J Forensic Leg Med. 2010;17:140–142.

38. Henry, T. Characteristics of sex related homicides in Alaska. J Forensic Nurs. 2010;6:57–65.

39. Slaughter, L, Brown, C, Shackleford, S, Peck, R. Patterns of genital injury in victims of sexual assault. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:609–616.

40. Hazelwood, R, Warren, J. The criminal behavior of the serial rapist. FBI Law Enforc Bull. 1990;59:11–16.

41. Hazelwood, R. The behavior-oriented interview of rape victims: The key to profiling. FBI Law Enforc. 1983;52:8–15.

42. Magid, D. Changes in sexual assault over time: A prospective comparison of 1974-1991. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:608.

43. Read, K. Population-based study of police-reported sexual assault in Baltimore, Maryland. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:273–278.

44. Maguire, W, Goodall, E, Moore, T. Injury in adult female sexual assault complainants and related factors. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;142:149–153.

45. Palmer, C, McNulty, A, D’Este, C, Donovan, B. Genital injuries in women reporting sexual assault. Sex Health. 2004;1:55–59.

46. Sheridan, D, Nash, K. Acute injury patterns of intimate partner violence victims. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8:281–289.

47. Choon, H, Myers, WC, Heide, KM. An empirical analysis of 30 years of U.S. juvenile and adult sexual homicide offender data: Race and age differences in the victim-offender relationship. J Forensic Sci. 2010;55:1282–1290.

48. Spehr, A, Hill, A, Habermann, N, Briken, P, Berner, W. Sexual murderers with adult or child victims: Are they different? Sex Abuse. 2010;22:290–314.

49. Millar, G, Stermac, L, Addison, M. Immediate and delayed treatment seeking among adult sexual assault victims. Women Health. 2002;35:53–64.

50. Gibbon, C. Sexual assault and rape. Curr Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;14:356–362.

51. Campbell, R, Bybee, D. Emergency medical services for rape victims: Detecting the cracks in service delivery. Womens Health. 1997;3:75–101.

52. Ellison, SR, Subramanian, S, Underwood, R. The general approach and management of the sexual assault patient. Mo Med. 2008;105:435–440.

53. McGregor, MJ, du Mont, J, White, D, Coombes, M. Examination for sexual assault: Evaluating the literature for indicators of women centered care. Health Care Women Int. 2009;30:22–40.

54. California Emergency Management Agency. Forensic Medical Report: Acute (<72 hours) Adult/Adolescent Sexual Assault Examination. Sacramento, Calif: California Emergency Management Agency; 2001.

55. Slaughter, L, Henry, T. Rape: When the exam is normal. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22:7–10.

56. Ullman, S. A critical review of field studies on the link of alcohol and adult sexual assault in women. Aggress Violent Behav. 2003;8:471–486.

57. Scott, H, Beaman, R. Demographic and situational factors affecting injury, resistance, completion, and charges brought in sexual assault cases: What is best for arrest? Violence Vict. 2004;19:479–494.

58. Testa, M, Vanzile-Tamsen, C, Livingston, J. The role of victim and perpetrator intoxication on sexual assault outcomes. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:320–329.

59. O’Connor, PG, Schottenfeld, RS. Patients with alcohol problems. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:592–600.

60. Kilpatrick, DG, Acinero, R, Resnick, HS, Saunders, BE, Best, CL. A 2-year longitudinal analysis of the relationships between violent assault and substance use in women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:834–847.

61. Littleton, H, Grills-Taquechel, A, Axson, D. Impaired and incapacitated rape victims: Assault characteristics and postassault experiences. Violence Vict. 2009;24:439–457.

62. Cole, J, Logan, T. Sexual assault response teams’ responses to alcohol using victims. J Forensic Nurs. 2008;4:174–181.

63. Hammock, GS, Richardson, DR. Perceptions of rape: The influence of closeness of relationship, intoxication and sex of participant. Violence Vict. 1997;12:237–246.

64. Scully, D, Marolla, J. Convicted rapists’ vocabulary of motive: Excuses and justifications. Soc Probl. 1984;31:530–544.

65. Sachs, C, Chu, L. Predictors of genitorectal injury in female victims of sexual assault. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1146–1151.

66. Johnston, L. Contributions of drug epidemiology to the field of drug abuse prevention. Subst Use Misuse. 1997;32:1637–1642.

67. Johnston, LD, O’Malley, PM, Bachman, JG. National Survey Results on Drug Use: College Students and Young Adults from the Monitoring the Future Study, 1975-92. Washington, DC: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1993.

68. Slaughter, L. Involvement of drugs in sexual assault. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:425–430.

69. Juhascik, M, et al. An estimate of the proportion of drug-facilitation of sexual assault in four U.S. localities. J Forensic Sci. 2007;52:1396–1400.

70. Du Mont, J, Macdonald, S, Rotbard, N, Asllani, E, Bainbridge, D. Factors associated with suspected drug facilitated sexual assault. CMAJ. 2009;180:513–519.

71. Du Mont, J, et al. Drug facilitated sexual assault in Ontario, Canada: Toxicological and DNA findings. J Forensic Leg Med. 2010;17:333–338.

72. Parkin, MC, Brailsford, AD. Retrospective drug detection in cases of drug facilitated sexual assault: Challenges and perspectives for the forensic toxicologist. Bioanalysis. 2009;1:1001–1013.

73. Carr, M, Moettus, A. Developing a policy for sexual assault examinations on incapacitated patients and patients unable to consent. J Law Med Ethics. 2010;38:647–653.

74. Pierce-Weeks, J, Campbell, P. The challenges forensic nurses face when their patient is comatose: Addressing the needs of our most vulnerable patient population. J Forensic Nurs. 2008;4:104–110.

75. Eckert, LO, Sugar, N, Fine, D. Characteristics of sexual assault in women with a major psychiatric diagnosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1284–1291.

76. White, C, McLean, I. Adolescent complainants of sexual assault; injury patterns in virgin and non-virgin groups. J Clin Forensic Med. 2006;13:172–180.

77. Funk, M, Schuppel, J. Strangulation injuries. Wis Med J. 2003;102:41–45.

78. Wilbur, L, et al. Survey results of women who have been strangled while in an abusive relationship. J Emerg Med. 2001;21:297–302.

79. Prodan, M. Special Topics in Sexual Assault Investigations: Victim and Offender Relationship. Calif: Irvine; 2009.

80. Jones, JS, Rossman, L, Wynn, B, Ostovar, H. Assailants sexual dysfunction during rape: Prevalence and relationship to genital trauma in female victims. J Emerg Med. 2008;38:529–535.

81. Reznic, M, Nachman, R, Hiss, J. Penile lesions-reinforcing the case against suspects of sexual assault. J Clin Forensic Med. 2004;11:78–81.

82. State of California. California Penal Code. Section 222, Sacramento, CA.

83. Gray-Eurom, K, Seaberg, D, Wears, R. The prosecution of sexual assault cases: Correlation with forensic evidence. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:39–46.

84. Sweet, D, Shutler, G. Analysis of salivary DNA evidence from a bite mark on a body submerged in water. J Forensic Sci. 1999;44:1069.

85. Sweet, D, Lorente, M, Lorente, J, Valenzula, A, Villanueva, E. An improved method to recover saliva from human skin: The double swab technique. J Forensic Sci. 1997;42:320–322.

86. Crowley, S. The Medical Legal Examination. Stamford, Conn: Appleton & Lange; 1999.

87. Henry, T. Lip swabs, floss effective for collecting DNA evidence. On the Edge. 2003;9:7.

88. Giest, R. Sexually related trauma. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1988;6:439.

89. Kaufman, R, Faro, S. Benign Diseases of the Vulva and Vagina. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1994.

90. Masters, W, Johnson, V. Human Sexual Response. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1966.

91. Levin, R. The ins and outs of vaginal lubrication. Sex Relatsh Ther. 2003;18:509–513.

92. Sipski, M. Sexual response in women with spinal cord injury: Neurologic pathways and recommendations for the use of electrical stimulation. J Spinal Cord Med. 2001;24:155–158.

93. Sipski, M, Arenas, A. Female sexual function after spinal cord injury. Prog Brain Res. 2006;152:441–447.

94. Suschinsky, KD, Lalumière, ML. Prepared for anything? An investigation of female genital arousal in response to rape cues. Psychol Sci. 2011;22:159–165.

95. Levin, R, Van Berlo, W. Sexual arousal and orgasm in subjects who experience forced or non-consensual sexual stimulation. J Clin Forensic Med. 2004;11:82–88.

96. McLean, I, Roberts, SA, White, C, Paul, S. Female genital injuries resulting from consensual and non-consensual vaginal intercourse. Forensic Sci Int. 2011;204:27–33.

97. Zink, T, et al. Comparison of methods for identifying ano-genital injury after consensual intercourse. J Emerg Med. 2008;39:113–118.

98. Mancino, P, Parlavecchio, E, Melluso, J, Monti, M, Russo, P. Introducing colposcopy and vulvovaginoscopy as routine examinations for victims of sexual assault. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2003;30:40.

99. Slaughter, L, Brown, C. Colposcopy to establish physical findings in rape victims. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:83–86.

100. Fraser, I, et al. Variations in vaginal epithelial surface appearance determined by colposcopic inspection in healthy, sexually active women. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1974–1978.

101. Stevens, J, Rossman, L, Jones, J, Wynn, B. Effect of menstrual bleeding on the detection of anogenital injuries in sexual assault victims. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:134.

102. Morgan, J. Comparison of cervical os versus vaginal evidentiary findings during sexual assault exam. J Emerg Nurs. 2008;34:102–105.

103. Keller, P, Lechner, M. Injuries to the cervix in sexual assault victims. J Forensic Nurs. 2010;6:196–202.

104. Allard, J. The collection of data from findings in cases of sexual assault and the significance of spermatozoa on vaginal, anal, and oral swabs. Sci Justice. 1997;37:99.

105. Collins, KA, Bennett, AT. Persistence of spermatozoa and prostatic acid phosphatase in specimens form deceased individuals during varied postmortem intervals. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2001;22:228–232.

106. Young, KL, Jones, JG, Worthington, T, Simpson, P, Casey, PH. Forensic laboratory evidence in sexually abused children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:585–588.

107. Stefanidou, M, Alevisopoulos, G, Spiliopoulou, C. Fundamental issues in forensic semen detection. West Indian Med J. 2010;59:280–283.

108. Lauber, A, Souma, M. Use of toluidine blue for documentation of traumatic intercourse. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;60:644–648.

109. Hochmeister, M, et al. Effects of toluidine blue and destaining reagents used in sexual assault examinations on the ability to obtain DNA profiles from postcoital vaginal swabs. J Forensic Sci. 1997;42:316–319.

110. McCauley, J, Guzinski, G, Welch, R, Gorman, R, Osmens, F. Toluidine blue in the corroboration of rape in the adult victim. Am J Emerg Med. 1987;5:105–108.

111. Heger, A. Evaluation of sexual assault in the emergency department. Top Emerg Med. 1999;21:46–57.

112. Brennan, P. The medical and ethical aspects of photography in the sexual assault examination: Why does it offend? J Clin Forensic Med. 2006;13:194–202.

113. Workowski, KA, Berman, S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1–109.

114. Grimes, D, Raymond, E. Emergency contraception. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:180–189.

115. Langston, A. Emergency contraception: Update and review. Semin Reprod Med. 2010;28:95–102.

116. American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), Policy Statement: Emergency Contraception for Women at Risk of Unintended and Preventable Pregnancy. Irving, Texas:ACEP; 2010. www.acep.org/content.aspx?id=29200.

117. American Medical Association: Access to emergency contraception. Policy of the House of Delegates. H-75-985; 2011.

118. Kaplan, DW, et al. American Academy of Pediatrics. Care of the adolescent sexual assault victim. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1476–1479.

119. American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Emergency contraception. Practice Bulletin. 112, 2010.

120. Cremer, M, Masch, R. Emergency contraception: Past, present and future. Minerva Ginecol. 2010;62:361–371.

121. Espey, E, et al. Compliance with mandated emergency contraception in New Mexico emergency departments. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2009;18:619–623.

122. Dietz, T, Wright, J. Age and gender differences and predictors of victimization of the older homeless. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2005;17:37–60.

123. Poulos, CA, Sheridan, D. Genital injuries in postmenopausal women after sexual assault. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2008;24:323–335.

124. Burgess, A, Brown, K, Ledray, L. Sexual abuse of older adults. Am J Nurs. 2005;105:66–71.

125. Hanrahan, N, Burgess, A, Gerolamo, A. Core data elements tracking elder sexual abuse. Clin Geriatr Med. 2005;21:413–427.

126. Chihowski, K, Hughes, S. Clinical issues in responding to alleged elder sexual abuse. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2008;20:377–400.

127. Cooper, G, King, M. Interviewing the incarcerated offender convicted of sexually assaulting the elderly. J Forensic Nurs. 2006;2:130–133.

128. Burgess, A, Hanrahan, N, Baker, T. Forensic markers in elder female sexual abuse cases. Clin Geriatr Med. 2005;21:399–412.

129. Collins, K, Presnell, S. Elder homicide: A 20-year study. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2006;27:183–187.

130. Templeton, D. Sexual assault of a postmenopausal woman. J Clin Forensic Med. 2005;12:98–100.

131. Jones, JS, Rossman, L, Diegel, R, Van Order, P, Wynn, B. Sexual assault in postmenopausal women: Epidemiology and patterns of genital injury. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:922–929.

132. Del Bove, G, Stermac, L, Bainbridge, D. Comparisons of sexual assault among older and younger women. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2005;17:1–18.

133. Martin, S, Housley, C, Raup, G. Determining competency in sexually assaulted patient: A decision algorithm. J Forensic Leg Med. 2010;17:275–279.

134. Masho, SW, Anderson, L. Sexual assault in men: A population-based study of Virginia. Violence Vict. 2009;24:98–110.

135. Peterson, Z, Voller, EK, Polusny, M, Maureen, M. Prevalence and consequences of adult sexual assault of men: Review of empirical findings and state of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:1–24.

136. Monk-Turner, E, Light, D. Male sexual assault and rape: Who seeks counseling? Sex Abuse. 2010;22:255–265.

137. Pesola, G, Westfal, R, Kuffner, C. Emergency department characteristics of male sexual assault. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:792–798.

138. Lipscomb, GH, Muram, D, Speck, PM, Mercer, BM. Male victims of sexual assault. JAMA. 1992;267:3064.

139. Ernst, AA, Green, E, Ferguson, MT, Weiss, SJ, Green, WM. The utility of anoscopy and colposcopy in the evaluation of male sexual assault victims. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36:432.

140. Light, D, Monk-Turner, E. Circumstances surrounding male sexual assault and rape. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24:1849–1858.