Sexual and reproductive health

Contraception and termination of pregnancy

Artificial methods of contraception act predominantly by the following pathways:

• prevention of implantation of the fertilized ovum

• barrier methods of contraception, whereby the spermatozoa are physically prevented from gaining access to the cervix.

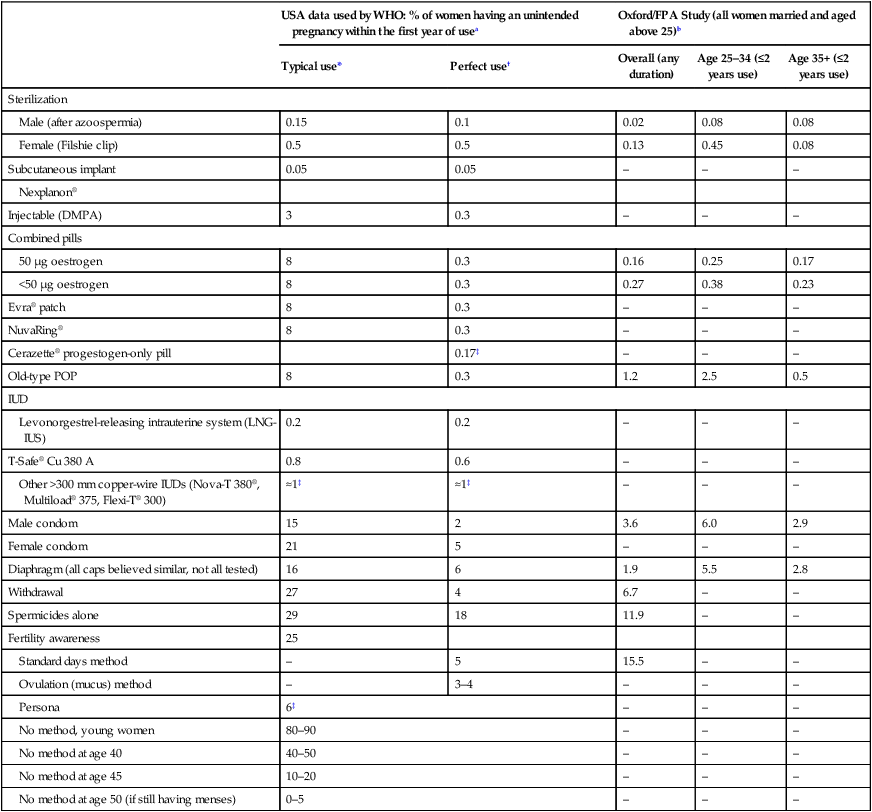

The effectiveness of any method of contraception is measured by the number of unwanted pregnancies that occur during 100 women years of exposure, i.e. during 1 year in 100 women who are normally fertile and are having regular coitus. This is known as the ‘Pearl index’ (Table 19.1).

Table 19.1

Failure rates per 100 women for different methods of contraception

| USA data used by WHO: % of women having an unintended pregnancy within the first year of usea | Oxford/FPA Study (all women married and aged above 25)b | ||||

| Typical use* | Perfect use† | Overall (any duration) | Age 25–34 (≤2 years use) | Age 35+ (≤2 years use) | |

| Sterilization | |||||

| Male (after azoospermia) | 0.15 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Female (Filshie clip) | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.13 | 0.45 | 0.08 |

| Subcutaneous implant | 0.05 | 0.05 | – | – | – |

| Nexplanon® | |||||

| Injectable (DMPA) | 3 | 0.3 | – | – | – |

| Combined pills | |||||

| 50 µg oestrogen | 8 | 0.3 | 0.16 | 0.25 | 0.17 |

| <50 µg oestrogen | 8 | 0.3 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.23 |

| Evra® patch | 8 | 0.3 | – | – | – |

| NuvaRing® | 8 | 0.3 | – | – | – |

| Cerazette® progestogen-only pill | 0.17‡ | – | – | – | |

| Old-type POP | 8 | 0.3 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 0.5 |

| IUD | |||||

| Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) | 0.2 | 0.2 | – | – | – |

| T-Safe® Cu 380 A | 0.8 | 0.6 | – | – | – |

| Other >300 mm copper-wire IUDs (Nova-T 380®, Multiload® 375, Flexi-T® 300) | ≈1‡ | ≈1‡ | – | – | – |

| Male condom | 15 | 2 | 3.6 | 6.0 | 2.9 |

| Female condom | 21 | 5 | – | – | – |

| Diaphragm (all caps believed similar, not all tested) | 16 | 6 | 1.9 | 5.5 | 2.8 |

| Withdrawal | 27 | 4 | 6.7 | – | – |

| Spermicides alone | 29 | 18 | 11.9 | – | – |

| Fertility awareness | 25 | ||||

| Standard days method | – | 5 | 15.5 | – | – |

| Ovulation (mucus) method | – | 3–4 | – | – | – |

| Persona | 6‡ | – | – | – | |

| No method, young women | 80–90 | – | – | – | |

| No method at age 40 | 40–50 | – | – | – | |

| No method at age 45 | 10–20 | – | – | – | |

| No method at age 50 (if still having menses) | 0–5 | – | – | – | |

Other Notes (1) Note influence of age: all the rates in the fifth column being lower than those in the fourth column. Lower rates still may be expected above age 45. (2) Much better results also obtainable in other states of relative infertility, such as lactation. (3) Oxford/fpa users were established users at recruitment – greatly improving results for barrier methods (Qs 1.19, 4.9). (4) The Nexplanon, Cerazette and Persona results come from pre-marketing studies by the manufacturer, giving an estimate of the Pearl ‘method-failure’ rate.

bVessey M, Lawless M, Yeates D (1982) Efficacy of different contraceptive methods. Lancet 1(8276):841–842.

*Typical use: Among typical couples who initiate use of the method (not necessarily for the first time), the percentage who experience an accidental pregnancy during the first year if they do not stop use for any other reason.

†Perfect use: Among typical couples who initiate use of the method (not necessarily for the first time), and who then use it perfectly (both consistently and correctly), the percentage who experience an accidental pregnancy during the first year if they do not stop use for any other reason.

‡Data not available from Trussell, so best alternative data given, e.g. from manufacturer’s studies.

(This Table was published in Guillebaud J, MacGregor A (2013) Contraception 6e. ©Elsevier. Reproduced from Trussell J, Wyn LL (2008) Reducing unintended pregnancy in the United States. Contraception 77(1): 1–5, with permission.)

Barrier methods of contraception

Diaphragms and cervical caps

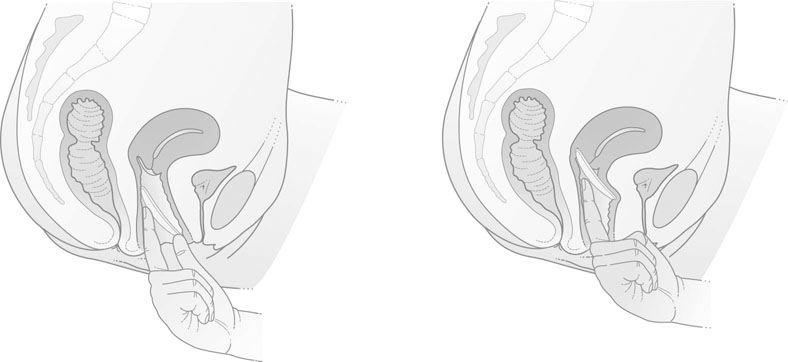

The modern vaginal diaphragm consists of a thin latex rubber dome attached to a circular metal spring. These diaphragms vary in size from 45–100 mm in diameter. The size of the diaphragm required is ascertained by examination of the woman. The size and position of the uterus are determined by vaginal examination and the distance from the posterior vaginal fornix to the pubic symphysis is noted. The appropriate measuring ring, usually between 70 mm and 80 mm, is inserted. When in the correct position the anterior edge of the ring or diaphragm should lie behind the pubic symphysis and the lower posterior edge should lie comfortably in the posterior fornix (Fig. 19.1).

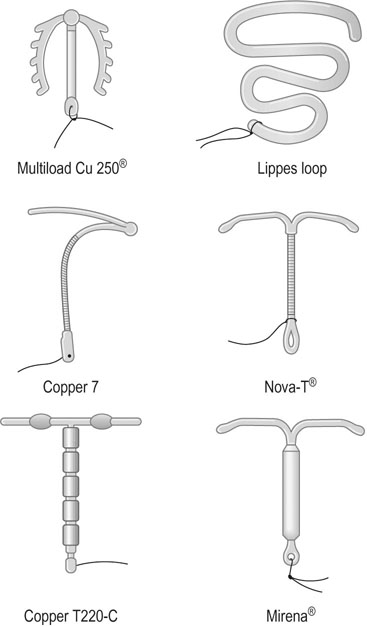

Intrauterine contraceptive devices

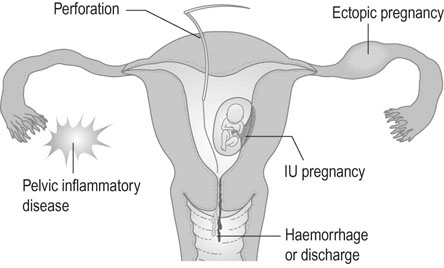

Intrauterine contraception is used by 6–8% of women in the UK. A wide variety of intrauterine devices (IUDs) have been designed for insertion into the uterine cavity (Fig. 19.2). These devices have the advantage that, once inserted, they are retained without the need to take alternative contraceptive precautions. It seems likely that they act mainly by preventing fertilization. This is a result of a reduction in the viability of ova and the number of viable sperm reaching the tube.

Types of devices

The devices are either inert or pharmacologically active.

Devices containing progestogen

The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system or Mirena® contains 52 mg of levonorgestrel (Fig. 19.2) which suppresses the normal build up of the endometrium so that, unlike most IUDs, it causes a reduction in menstrual blood loss. However, there is a high incidence of irregular scanty bleeding in the first 3 months after insertion of the device. Unlike previous progestogen-containing devices it does not appear to be associated with a higher risk of ectopic pregnancy. The superior efficacy of third-generation copper IUDs and the levonorgestrel-releasing system means that these are now considered the devices of choice.

Complications

The complications of IUDs are summarized in Figure 19.3.

Perforation of the uterus

• The device has been expelled.

• The device has turned in the uterine cavity and drawn up the strings.

• The device has perforated the uterus and lies either partly or completely in the peritoneal cavity.

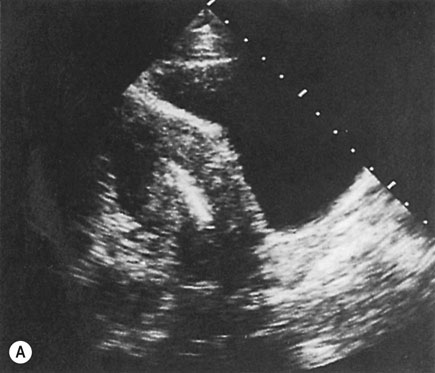

If there is no evidence of pregnancy, an ultrasound examination of the uterus should be performed. If the device is located within the uterine cavity (Fig. 19.4A), unless part of the loop or strings is visible, it will generally be necessary to remove the device with formal dilatation of the cervix under general or local anaesthesia. If the device is not found in the uterus, a radiograph of the abdomen will reveal the site in the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 19.4B). It is advisable to remove all extrauterine devices by either laparoscopy or laparotomy. Inert devices can probably be left with impunity, but copper devices promote considerable peritoneal irritation and should certainly be removed.

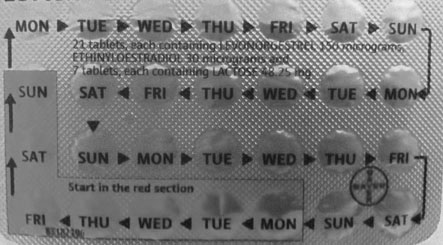

Hormonal contraception

Contraindications

There are various contraindications to the pill, some being more absolute than others.

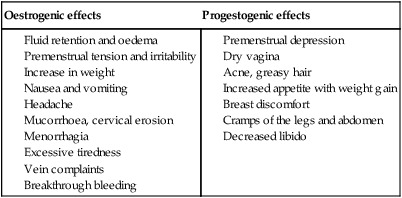

The occurrence of migraine for the first time, severe headaches or visual disturbances, or transient neurological changes are indications for immediate cessation of the pill. There are a series of minor side effects that may sometimes be used to advantage or may be offset by using a pill with a different combination of steroids (Table 19.2).

Table 19.2

Minor side effects of combined oral contraception

| Oestrogenic effects | Progestogenic effects |

Interaction between drugs and contraceptive steroids

Many drugs affect the contraceptive efficacy of the pill, and therefore additional precautions should be taken (Table 19.3). Vomiting and diarrhoea also result in loss of the pill and hence the return of fertility – particularly with the low-dose pills now widely in use. Progestogen-only pills must be taken every day if they are to be effective.

Table 19.3

Interaction of various drugs with oral contraceptives

| Interacting drug | Effects of interaction |

| Analgesics | Possible increased sensitivity to pethidine |

| Anticoagulants | Possible reduction of effect of anticoagulant – increased dosage of anticoagulant may be necessary |

| Anticonvulsants | Possible decrease in contraceptive reliability |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Reduced antidepressant response; increase in antidepressant toxicity |

| Antihistamines | Possible decrease in contraceptive reliability |

| Antibiotics | Possible decrease in contraceptive reliability Possibility of breakthrough bleeding (this is most likely with rifampicin) |

| Hypoglycaemic agents | Control of diabetes may be reduced |

| Antiasthmatics | Asthmatic condition may be exacerbated by concomitant oral contraceptive |

| Systemic corticosteroids | Increased dosage of steroids may be necessary |

Emergency contraception

• Her next period might be early or late.

• She needs to use barrier contraception until then.

• She needs to return if she has any abdominal pain or if the next period is absent or abnormal.

If the next period is more than 5 days overdue, pregnancy should be excluded. Emergency contraception prevents 85% of expected pregnancies. Efficacy decreases with time from intercourse.

Non-medical methods of contraception

Natural methods of family planning include the following:

• The rhythm method: Avoiding intercourse mid-cycle and for 6 days before ovulation and 2 days after it. The efficacy of this method depends on being able to predict the time of ovulation. If a regular 28 day cycle occurs, ovulation is predicted for day 14, and abstinence should be from days 8 to 16. If the cycles are very variable, varying between 24 and 32 days, the earliest ovulation would be on day 10 and the latest on day 18, so abstinence would be required between days 4 and 20.

• The ovulation method: This method takes into account the ability of a woman to recognize the increase in vaginal wetness due to cervical mucus productionin the phase before ovulation, and abstaining from sex during that time and for 2 days after the peak wetness has been observed. This method is much better than the rhythm method, but many women only get 4 days advanced warning of the time of ovulation, so intercourse on the preceding 2 days can result in a pregnancy.

• Coitus interruptus (withdrawal): A traditional and still widely used method of contraception that relies on withdrawal of the penis before ejaculation. It is not a particularly reliable method of contraception, because the best sperm often reach the tip of the penis before the male experiences the imminent ejaculation, or he forgets in the ‘heat’ of the moment.

• Lactational amenorrhoea method: Breastfeeding has historically been the most important means of family ‘spacing’. Ovulation resumes on average 4–6 months later in women who continue to breastfeed. During the first 6 months after birth this is an effective method of contraception in mothers providing they are fully breastfeeding, not giving the baby any non-breast milk or other food, AND have remained amenorrhoeic, with failure rates as low as 1/100 women being seen.

Sterilization

Counselling

With the improvements brought about by microsurgery, it is no longer acceptable to say that sterilization is irreversible and the patient should be counselled according to the technique to be used. The partner to be sterilized will be a matter of choice and motivation. If one partner has a reduced life expectancy from chronic illness, then that partner should be sterilized.

Techniques

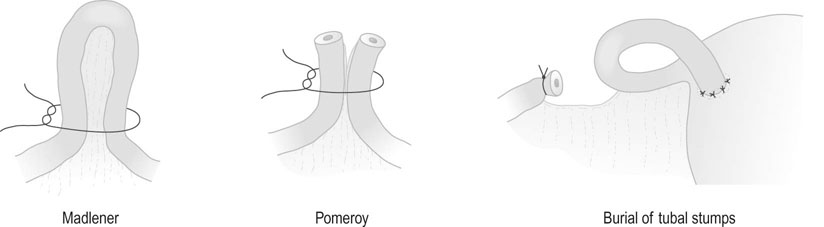

Female sterilization

• Tubal clips. This is the most widely used method of sterilization in the UK and Australia. The clips are made of plastic and inert metals and are locked on to the tube (Fig. 19.6). They have the advantage of causing minimal damage to the tube, but their disadvantage is a higher failure rate. Failures may be due to application on the wrong structure, extrusion of the tube from the clip, recanalization or fracture of the clip so that it falls off the tube. The Filshie clip, which has a titanium frame lined by silicone rubber, has the lowest failure rate (0.5%) and is easier to apply. Yoon or Fallope rings are applied over a loop of tube and are similar to a Madlener procedure (see below). This technique is associated with considerably greater abdominal pain postoperatively, and the failure rates vary between 0.3% and 4%. The rings are not suitable for application to the tubes in the puerperium when the tube is swollen and oedematous.

• Tubal coagulation and division. Sterilization is effected by either unipolar or bipolar diathermy of the tubes in two sites 1–2 cm from the uterotubal junction. A considerable amount of tube can be destroyed with this technique. Division of the diathermied tube is said to reduce the risk of ectopic pregnancy. The failure rate depends on the length of tube destroyed. Because of the risk of thermal bowel injury with subsequent leakage and faecal peritonitis, diathermy should not be used as the primary method of sterilization unless mechanical methods of tubal occlusion are technically difficult or fail at the time of the procedure.

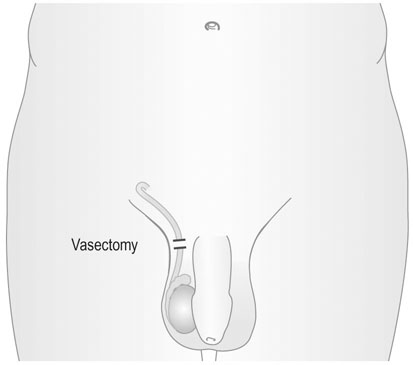

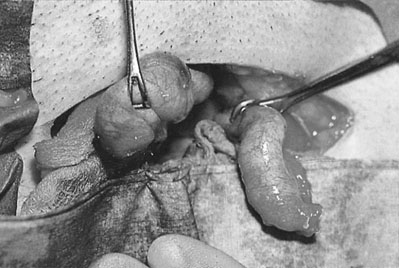

Vasectomy

This procedure is generally performed under local anaesthesia. Two small incisions are made over the spermatic cord and 3–4 cm of the vas deferens is excised (Fig. 19.8). The advantage of the technique is its simplicity. The disadvantages are that sterility is not immediate and should not be assumed until all spermatozoa have disappeared from the ejaculate. On average, this takes at least 10 ejaculations.

Termination of pregnancy

In the UK this is carried out in approved centres under the provisions of the Abortion Act 1967. This requires that two doctors agree that either continuation of the pregnancy would involve greater risk to the physical or mental health of the mother or her other children than termination, or that the fetus is at risk of an abnormality likely to result in it being seriously handicapped (Box 19.2). The most recent amendment to the Act (1991) set a limit for termination under the first of these categories at 24 weeks, although in practice the majority of terminations are carried out prior to 20 weeks.

Genital tract infections

There are other natural barriers to infection:

• The physical apposition of the pudendal cleft and the vaginal walls.

• Vaginal acidity – the low pH of the vagina in the sexually mature female provides a hostile environment for most bacteria; this resistance is weakened in the prepubertal and postmenopausal female.

• Cervical mucus that acts as a barrier in preventing the ascent of infection.

Lower genital tract infections

Common organisms causing lower genital tract infections

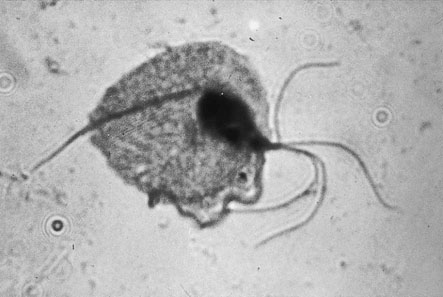

Trichomoniasis

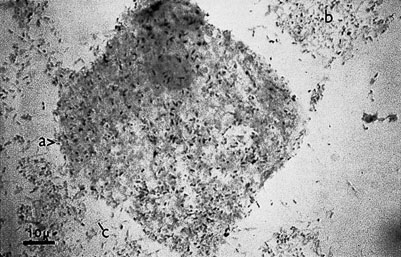

Trichomonas vaginalis is a flagellated single-celled protozoal organism that may infect the cervix, urethra and vagina. In the male the organism is carried in the urethra or prostate and infection is sexually transmitted. The organisms are often seen on the Pap smear even in the absence of symptoms. The commonest presentation is with abnormal vaginal bleeding, but other symptoms include vaginal soreness and pruritus. The vaginal pH is usually raised above 4.5. A fresh wet preparation in saline of vaginal discharge will show motile trichomonads (Fig. 19.9). The characteristic flagellate motion is easily recognized and the organism can be cultured.

Genital herpes

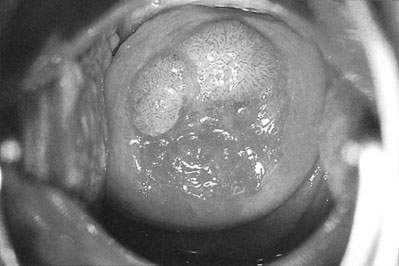

The condition is caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 2 and, less commonly, type 1. It is a sexually transmitted disease. Primary HSV infection is usually a systemic infection with fever, myalgia and occasionally meningism. The local symptoms include vaginal discharge, vulval pain, dysuria and inguinal lymphadenopathy. The discomfort may be severe enough to cause urinary retention. Vulval lesions include skin vesicles and multiple shallow skin ulcers (Fig. 19.10). The infection is also associated with an increased risk of cervical dysplasia. Partners may be asymptomatic and the incubation period is 2–14 days.

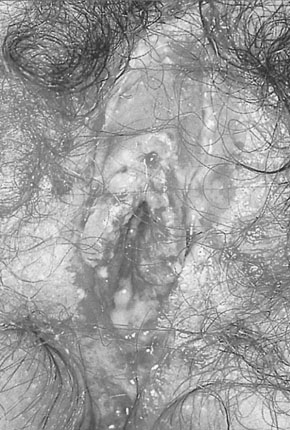

Genital warts (condylomata acuminata)

Vulval and cervical warts (Fig. 19.12) are caused by a human papilloma virus (HPV). The condition is commonly, although by no means invariably, transmitted by sexual contact. The incubation period is up to 6 months. The incidence has risen significantly over the last 15 years, particularly in women aged 16–25 years.

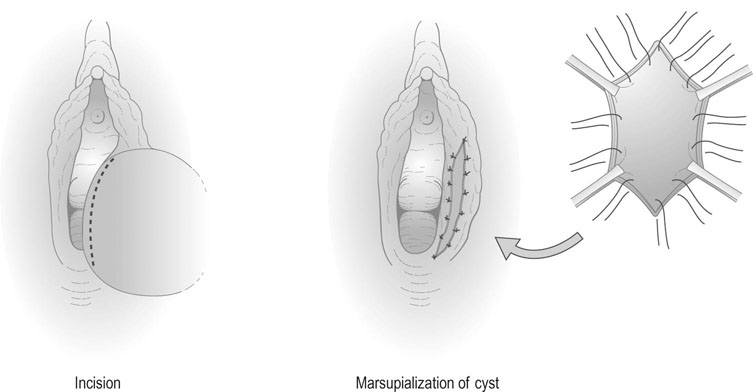

Treatment of lower genital tract infections

Infections of Bartholin’s gland are treated with the antibiotic appropriate to the organism. If abscess formation has occurred, the abscess should be ‘marsupialized’ by excising an ellipse of skin and sewing the skin edges to result in continued open drainage of the abscess cavity (Fig. 19.13). This reduces the likelihood of recurrence of the abscess.

Upper genital tract infections

Symptoms and signs

The symptoms of acute salpingitis include:

• Acute bilateral lower abdominal pain: Salpingitis is almost invariably bilateral; where the symptoms are unilateral, an alternative diagnosis should be considered

The signs include:

• Signs of systemic illness with pyrexia and tachycardia.

• Signs of peritonitis with guarding, rebound tenderness and often localized rigidity. (It should be noted that guarding and rigidity rarely are seen if blood is in the peritoneal cavity, such as due to an ectopic pregnancy, whereas tenderness and release tenderness are seen even in the absence of peritonitis.)

• On pelvic examination, acute pain on cervical excitation and thickening in the vaginal fornices, which may be associated with the presence of cystic tubal swellings due to pyosalpinges or pus-filled tubes; fullness in the pouch of Douglas suggests the presence of a pelvic abscess (Fig. 19.14).

• An acute perihepatitis occurs in 10–25% of women with chlamydial PID, which may cause right upper quadrant abdominal pain, deranged liver function tests and multiple filmy adhesions between the liver surface and the parietal peritoneum, and is known as the Fitz–Hugh–Curtis syndrome.

• A pyrexia of 38°C or more, sometimes associated with rigors.

Common organisms

Gonorrhoea

N. gonorrhoeae is a Gram-negative intracellular diplococcus (Fig. 19.15). Infection is commonly asymptomatic or associated with vaginal discharge. In cases of PID it spreads across the surface of the cervix and endometrium and causes tubal infection within 1–3 days of contact. It is the principal cause for 14% of cases of PID and occurs in combination with Chlamydia in a further 8%.

Differential diagnosis

• Tubal ectopic pregnancy: Initially pain is unilateral in most cases. There may be syncopal episodes and signs of diaphragmatic irritation with shoulder tip pain. The white cell count is normal or slightly raised but the haemoglobin level is likely to be low depending on the amount of blood lost, whereas in acute salpingitis the white cell count is raised and the haemoglobin concentration is normal.

• Acute appendicitis: The most important difference in the history lies in the unilateral nature of this condition. Pelvic examination does not usually reveal as much pain and tenderness but it must be remembered that the two conditions sometimes coexist, particularly where the infected appendix lies adjacent to the right Fallopian tube.

• Acute urinary tract infections: These may produce similar symptoms but rarely produce signs of peritonism and are commonly associated with urinary symptoms.

Management

• Fluid replacement by intravenous therapy – vomiting and pain often result in dehydration.

• When PID is clinically suspected, antibiotic therapy should be commenced. Antibiotic therapy initially prescribed for clinically diagnosed PID should be effective against C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae and the anaerobes characterizing bacterial vaginosis. If the woman is acutely unwell, treatment should be started with an antibiotic such as cefuroxime and metronidazole given intravenously with oral doxycycline until the acute phase of the infection begins to resolve. Treatment with oral metronidazole and doxycycline should then be continued for 7 and 14 days, respectively.

• Pain relief with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

• If the uterus contains an intrauterine device, it should be removed as soon as antibiotic therapy has been commenced.

• Bed rest – immobilization is essential until the pain subsides.

Patients who are systemically well can be treated as outpatients, with a single dose of azithromycin and a 7-day course of doxycycline, reviewed after 48 hours.

Chronic pelvic infection

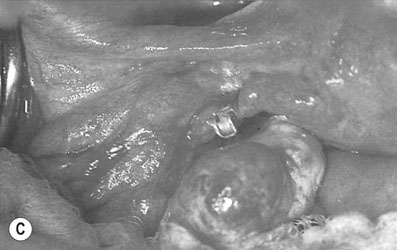

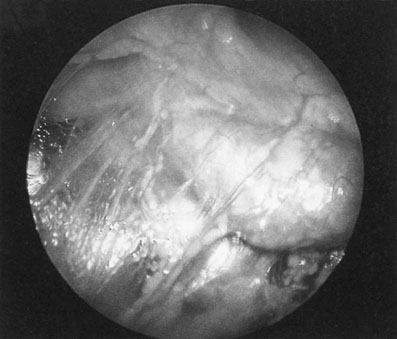

Acute pelvic infections may progress to a chronic state with dilatation and obstruction of the tubes forming bilateral hydrosalpinges with multiple pelvic adhesions (Fig.19.16).

Human immunodeficiency virus

The main clinical states can be identified as:

• a ‘flu-like’ illness 3–6 months after infection, associated with seroconversion

• asymptomatic impaired immunity

• persistent generalized lymphadenopathy

• AIDS-related complex with pathognomonic infections or tumours.

Common opportunistic infections include Candida, HSV, HPV, Mycobacterium spp., Cryptosporidium spp., Pneumocystis carinii and cytomegalovirus. Non-infective manifestations include weight loss, diarrhoea, fever, dementia, Kaposi’s sarcoma and an increased risk of cervical cancer.

Disorders of female sexual function

Dyspareunia

Superficial dyspareunia

• Infection: Local infections of the vulva and vagina commonly include monilial and trichomonal vulvovaginitis. Infections involving Bartholin’s glands also cause dyspareunia.

• Narrowing of the introitus may be congenital, with a narrow hymenal ring or vaginal stenosis. It may sometimes be associated with a vaginal septum. The commonest cause of narrowing of the introitus is the over-vigorous suturing of an episiotomy wound or vulval laceration or following vaginal repair of a prolapse.

• Menopausal changes: Atrophic vaginitis or the narrowing of the introitus and the vagina from the effects of oestrogen deprivation may cause dyspareunia. Atrophic vulval conditions such as lichen sclerosus can also cause pain.

• Vulvodynia: This is a condition of unknown aetiology characterized by persisting pain over the vulva.

• Functional changes: Lack of lubrication associated with inadequate sexual stimulation and emotional problems will result in dyspareunia.

Deep dyspareunia

• Acute or chronic pelvic inflammatory disease: including cervicitis, pyosalpinx and salpingo-oophoritis (Fig. 19.16). The uterus may become fixed. Ectopic pregnancy must also be considered in the differential diagnosis in this group.

• Retroverted uterus and prolapsed ovaries: If the ovaries prolapse into the pouch of Douglas and become fixed in that position, intercourse is painful on deep penetration.

• Endometriosis: Both the active lesions and the chronic scarring of endometriosis may cause pain.

• Neoplastic disease of the cervix and vagina: At least part of the pain in this situation is related to secondary infection.

• Postoperative scarring: This may result in narrowing of the vaginal vault and loss of mobility of the uterus. The stenosis commonly occurs following vaginal repair and, less often, following repair of a high vaginal tear. Vaginal scarring may also be caused by chemical agents such as rock salt, which, in some countries, is put into the vagina in order to produce contracture.

• Foreign bodies: Occasionally, a foreign body in the vagina or uterus may cause pain in either the male or female partner. For example, the remnants of a broken needle or partial extrusion of an intrauterine device may cause severe pain in the male partner.

Treatment

Medical treatment for deep dyspareunia includes the use of antibiotics and antifungal agents for pelvic infection, and the use of local or oral hormone therapy for post-menopausal atrophic vaginitis. Treatment for endometriosis is discussed in Chapter 17. Surgical treatment includes correction of any stenosis, excision of painful scars where appropriate, and reassurance and sexual counselling is necessary in functional disorders.

Disorders of male sexual function

The principal features of sexual dysfunction in men are:

All or any of these may be present from adolescence or have their onset at any time of life after a period of healthy sexuality. The causes of loss of libido have been previously described above under female sexual dysfunction.