Problem 48 Severe dehydration in a young woman

There are a number of possible causes for this woman’s comatose state.

You have a working diagnosis for this patient who is critically ill.

The patient decides to curtail her backpacking holiday and return home.

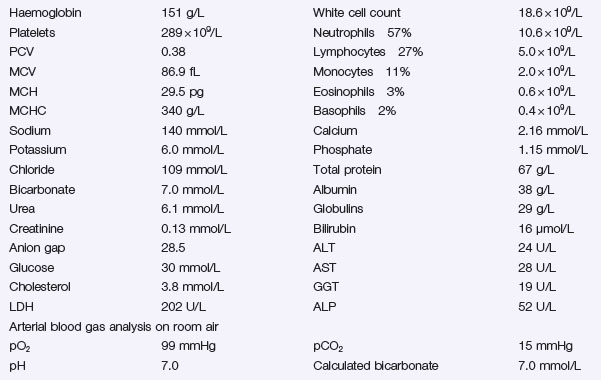

Answers

A.1 Her Glasgow coma score is 11 (E4, V2, M5).

A.3 As part of the immediate management, the following must be undertaken:

Metabolic acidosis can be divided into:

Fluid and Sodium Replacement

Correction of Acidosis and Hyperglycaemia with Insulin

Insulin therapy will correct both the acidosis and hyperglycaemia.

Potassium Replacement

Prevention of the Complications of Ketoacidosis

Insulin infusion is ceased 1 hour after the first dose of subcutaneous insulin is given.

In Hospital:

As an Outpatient

Revision Points

Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Treatment

Intravenous insulin infusion allows a gradual and steady correction of the metabolic abnormalities.