60 Severe Asthma Exacerbation

Magnitude of the Problem

Magnitude of the Problem

Each year in the United States, acute asthma accounts for approximately 1.8 million emergency department visits, 497,000 hospitalizations, and 3800 deaths.1 All too commonly, failure to achieve adequate outpatient control lies at the crux of the problem. Asthma control is achieved in a minority of patients, largely due to the underuse of antiinflammatory agents, and poor control is a risk factor for asthma exacerbation.2 More than half of current asthmatics had one or more attacks during the preceding year, and there appears to be a subset of patients who are prone to exacerbations. Factors underlying the exacerbation-prone phenotype include cigarette smoking, medication nonadherence, psychosocial factors, poverty, obesity, and alterations in host cytokine response to viral infections.3 The rate of asthma death is higher in blacks than whites and in patients aged 65 and older. Patients who require mechanical ventilation for asthma have a mortality rate of less than 10% and are most likely to die of tension pneumothorax or nosocomial infection.4 Fortunately, the rate of asthma death (which had increased from 1980 to 1995) has decreased each year since 2000. Risk factors for fatal or near-fatal asthma are listed in Table 60-1.

Pathophysiology of Acute Airflow Obstruction

Pathophysiology of Acute Airflow Obstruction

Regardless of the tempo of the attack, acutely ill asthmatics develop critical airflow obstruction. The time available for expiration (less than 2 seconds in a patient breathing 30/min) is insufficient for full exhalation, resulting in gas trapping and dynamic lung hyperinflation (DHI). Trapped gas elevates alveolar volume and pressure relative to mouth pressure at end-expiration, a state referred to as auto-PEEP.5 Auto-PEEP must be overcome by forcefully lowering pleural pressure during spontaneous inspiration, which increases the inspiratory work of breathing. At the same time, dynamic hyperinflation increases elastic work of breathing. Dynamic hyperinflation also decreases diaphragm force generation by placing the diaphragm in a mechanically disadvantageous position. Dynamic hyperinflation may be self-limiting because increases in lung volume increase lung elastic recoil pressure and airway diameter to augment expiratory flow. In the end, an imbalance between increased respiratory system load (both resistive and elastic) and decreased respiratory muscle strength may result in respiratory failure.6

Clinical Features

Clinical Features

Dyspnea, cough, wheeze, and increased work of breathing are the hallmarks of acute asthma. Patients with moderate to moderately severe attacks are tachypneic and in mild to moderate respiratory distress. They have expiratory phase prolongation, difficulty speaking in long sentences, and audible wheezes. Arterial blood gases commonly reveal hypoxemia and acute respiratory alkalosis. A more severe attack leads to upright positioning, diaphoresis, monosyllabic speech, respiratory rate above 30/min, accessory muscle use, pulse above 120/min, pulsus paradoxus greater than 25 mm Hg, hypoxemia, and normo- or hypercapnia. Depressed mental status, paradoxical respiration, bradycardia, absence of pulsus paradoxus from respiratory muscle fatigue, and a quiet chest signal an impending arrest. The emergence of wheezes in these patients is generally a good marker that airflow has improved. Thus posture, speech, and mental status allow for a quick appraisal of severity, response to therapy, and need for intubation.7

Emergency Department Disposition

Emergency Department Disposition

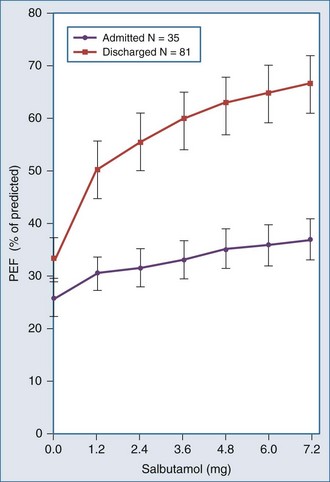

Asthmatic patients with inadequate response to albuterol in the ED invariably require hospital admission or prolonged treatment in an ED holding area (see later).8 Approximately one-third of patients are nonresponders to albuterol (Figure 60-1), which is not necessarily explained by prior heavy use of this medication. Rather, nonresponsiveness suggests a significant component of airway wall inflammation and the presence of intraluminal mucus. Albuterol nonresponders have negligible (i.e., <10%) changes in their PEFR after 30 to 60 minutes of therapy. These patients should be admitted to the hospital, as should patients with other markers of a severe attack such as a PEFR less than 40% of predicted or personal best PEFR, or deterioration despite ED treatment. Patients with respiratory failure, need for frequent albuterol treatments, fatigue, altered mental status, and cardiac arrhythmias require intensive care unit admission. Patients with an incomplete response to treatment in the ED, defined by improved but persistent symptoms and a PEFR or FEV1 between 40% and 69% of predicted, should be considered for admission, although selected patients safely return home with appropriate treatment and follow-up. Patients with a good response to treatment may be discharged home with appropriate instructions for anti-inflammatory therapy. These patients have a PEFR ≥ 70% an hour after their last treatment, a clear chest, and are in no distress.

Pharmacologic Management

Pharmacologic Management

Selected drugs used in the treatment of acute asthma are presented in Table 60-2. Brief discussions of a few of the more common therapeutic agents employed to treat severe asthma exacerbation follow.

TABLE60-2 Selected Drugs Used in the Treatment of Acute Asthma

| Albuterol | 2.5 mg in 2.5 mL normal saline by nebulization every 15-20 min × 3 in the first hour or 4-8 puffs by MDI with spacer every 10-20 min for 1 hour, then as required; for intubated patients, titrate to physiologic effect and side effects. |

| Levalbuterol | 1.25 mg by nebulization every 15-20 min × 3 in the first hour, then as required. |

| Epinephrine | 0.3 mL of a 1 : 1000 solution subcutaneously every 20 min × 3. Terbutaline is favored in pregnancy when parenteral therapy is indicated. Use with caution in patients older than age 40 and in patients with coronary artery disease. |

| Corticosteroids | Methylprednisolone IV or prednisone PO 40-80 mg/d in 1 or 2 divided doses until PEFR reaches 70% of predicted or personal best. |

| Anticholinergics | Ipratropium bromide 0.5 mg (with albuterol) by nebulization every 20 min, or 8 puffs by MDI with spacer (with albuterol) every 20 min. |

| Magnesium sulfate | 2 g IV over 20 minutes, repeat once as required (total dose 4 g, unless hypomagnesemic). |

IV, intravenous; MDI, metered-dose inhaler; PEFR, peak expiratory flow rate; PO, per os (oral).

Noninvasive Ventilation

Noninvasive Ventilation

Noninvasive ventilation includes the use of low levels of nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) of 5 to 7.5 cm H2O or, more commonly, bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP). One approach to BiPAP use is to start with 8 cm H2O inspiratory pressure support and 3 cm H2O of expiratory positive airway pressure. These pressures can be adjusted as required to 15 cm H2O for inspiration and 5 cm H2O during expiration to achieve common endpoints of improved patient comfort, RR below 25 and tidal volume above 7 mL/kg.9 Noninvasive ventilation should only be used in alert, cooperative, and hemodynamically stable patients who do not need an endotracheal tube for airway protection or secretion clearance.

Intubation and Mechanical Ventilation

Intubation and Mechanical Ventilation

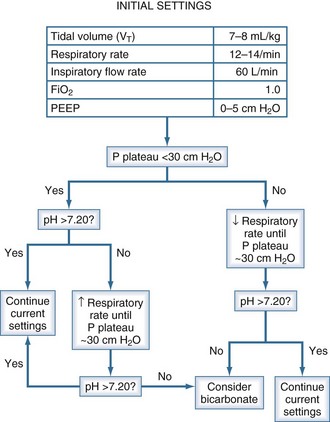

Initial Ventilator Settings

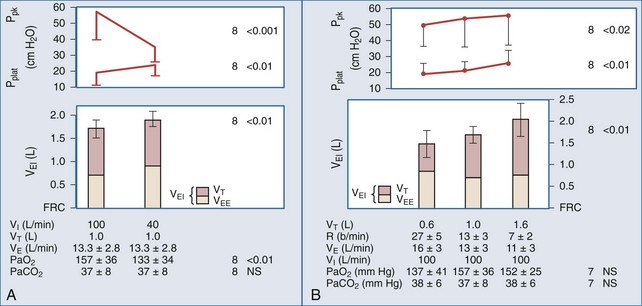

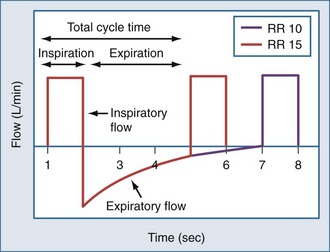

Expiratory time (Te), tidal volume (VT), and the severity of airway obstruction determine the level of dynamic hyperinflation during mechanical ventilation (Figure 60-2).10,11 Expiratory time is determined by minute ventilation (RR × VT) and the inspiratory flow rate. To illustrate this point, consider the following hypothetical ventilator settings: RR 15/min; VT 1000 mL, and an inspiratory flow rate of 60 LPM (or 1 LPS). In this example, the respiratory cycle time (the total amount of time allowed for one complete breath) is 4 seconds (Figure 60-3). Inspiratory time (Ti) is 1 second, and Te is 3 seconds, resulting in an I : E of 1 : 3. If these settings caused critical dynamic hyperinflation, lowering RR to 10/min would prolong respiratory cycle time to 6 seconds and Te to 5 seconds (I : E of 1 : 5), thus providing additional exhalation time. Granted, the additional volume of gas emptied by this strategy may be small because of low expiratory flow rates, but even small changes in lung volume may be clinically relevant. Now consider the effect of increasing inspiratory flow. If inspiratory flow is increased from 60 LPM to 120 LPM, then Ti would decrease to 0.5 seconds, and with a RR of 15/min, Te would increase from 3 seconds to 3.5 seconds. High inspiratory flow rates, however, increase peak airway pressures, and though high peak airway pressures themselves do not correlate with outcome, they might worsen patient-machine synchrony. Furthermore, high inspiratory flow rates may have the untoward effect of increasing respiratory rate in spontaneously breathing patients, thereby decreasing Te. On the other hand, if too low an inspiratory flow is used, Te falls and dynamic hyperinflation increases.

A reasonable compromise is to choose an inspiratory flow rate of 60 LPM and an initial minute ventilation of 7 to 8 L/min in a 70-kg patient to avoid dangerous levels of dynamic hyperinflation.12 This can be achieved by setting the RR between 12 and 14/min and VT between 7 and 8 mL/kg. In spontaneously breathing patients, low levels of machine-set PEEP (e.g., 5 cm H2O) decrease inspiratory work of breathing by decreasing the pressure gradient required to overcome auto-PEEP, without aggravating lung inflation. There are no randomized trials of ventilator mode in acute asthma. In paralyzed patients and other patients not breathing above the set respiratory rate, synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation (SIMV) and assist-controlled ventilation (AC) are identical. In patients triggering the ventilator, AC may increase Ve more than SIMV, but SIMV may increase work of breathing. Depending on the institution, volume-controlled ventilation (VC) may be recommended over pressure-controlled ventilation (PC) because of greater staff familiarity with its use. Pressure control offers the advantage of limiting peak airway pressure to a predetermined set value (e.g., 30 cm H2O) and has been used successfully in children with severe asthma exacerbation. During PC, VT is inversely related to auto-PEEP, and Ve is not guaranteed, requiring appropriate use of minute ventilation/tidal volume alarms.

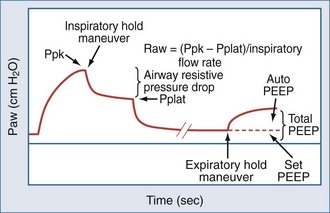

Assessing Lung Inflation

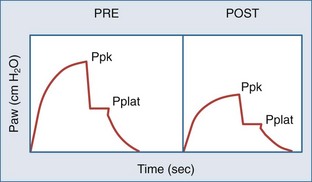

In concept, the degree of dynamic hyperinflation is central to ventilator adjustments, but there are inherent problems with measuring the degree of hyperinflation in clinical practice. The only validated method is to measure the volume gas at end-inspiration, termed Vei, by collecting expired gas from total lung capacity (TLC) to functional residual capacity (FRC) during 40 to 60 seconds of apnea. Although Vei may underestimate air trapping in the presence of slowly emptying lung units, a Vei greater than 20 mL/kg correlates with barotrauma. The utility of this measure is limited by the need for paralysis and staff expertise with expiratory gas collection. Alternate measures of lung inflation include the single-breath plateau pressure (Pplat) and auto-PEEP. Accurate measurements of Pplat and auto-PEEP require patient-ventilator synchrony and the absence of patient interference. Paralysis is generally not required. However, neither pressure has been validated as a predictor of outcome. Pplat (or lung distension pressure) is an estimate of average end-inspiratory alveolar pressure that is determined by briefly stopping flow at end-inspiration (Figure 60-4), but Pplat is also affected by properties of the chest wall and abdomen. For example, Pplat will be higher in a patient with abdominal distension or obesity for the same degree of hyperinflation. Nevertheless, experience suggests that a Pplat less than 30 cm H2O generally correlates with favorable outcomes.

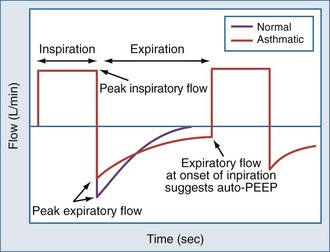

Auto-PEEP is the lowest average alveolar pressure achieved during the respiratory cycle. It is obtained by measuring airway opening pressure during an end-expiratory hold maneuver (Figure 4) and does not estimate end-inhalation volume or pressure. Persistence of expiratory gas flow at the beginning of inspiration (which can be detected by auscultation or flow tracings) also suggests auto-PEEP (Figure 60-5). As with Vei, auto-PEEP may underestimate the severity of dynamic hyperinflation when there is poor communication between the alveoli and airway opening. In general, however, auto-PEEP less than 15 cm H2O is likely acceptable.

Ventilator Adjustments

We offer the following approach to ventilator adjustments in severe asthma (Figure 60-6). This approach relies on Pplat as the measure of dynamic hyperinflation and arterial pH as a surrogate marker of ventilation. If initial ventilator settings result in Pplat above 30 cm H2O, RR should be reduced to decrease Pplat below 30 cm H2O. Decreasing RR may cause hypercapnia. Fortunately, hypercapnia is generally well tolerated in this patient population. Anoxic brain injury and myocardial dysfunction are contraindications to permissive hypercapnia because of the potential for hypercapnia to dilate cerebral vessels, decrease myocardial contractility, and constrict pulmonary vasculature. Lowering RR may not increase PaCO2 as much as expected if it decreases the degree of hyperinflation and thereby lowers dead space. If hypercapnia results in a blood pH of less than 7.20, and RR cannot be increased because Pplat is at its limit, we consider an infusion of sodium bicarbonate, although bicarbonate has not been shown to improve outcome. If Pplat is less than 30 cm H2O and pH is less than 7.20, RR can be safely increased until Pplat nears the 30 cm H2O limit.

Use of Bronchodilators During Mechanical Ventilation

Regardless of whether an MDI with spacer or nebulizer is used, higher drug dosages are required, and the dosage should be titrated to achieve a fall in the peak-to-pause airway pressure gradient (Figure 60-7). When no measurable drop in airway resistance occurs, other causes of elevated airway resistance such as a kinked or plugged endotracheal tube should be excluded. Moreover, it may be reasonable to consider a drug holiday in patients who do not demonstrate a physiologic response to appropriately delivered medications.

Postexacerbation Management

Postexacerbation Management

The importance of patient education, adherence to daily antiinflammatory controller medications, environmental control, and close follow-up cannot be overstated. Patients who have experienced severe asthma exacerbations are at risk for subsequent attacks and asthma-related death. In this regard, a recent tri-society task force report provides recommendations for antiinflammatory treatment after discharge and follow-up after acute asthma episodes.13,14

Key Points

1 Moorman JE, Rudd RA, Johnson CA, et al. National surveillance for asthma—United States, 1980-2004. MMWR Surveill Sum. 2007;56(8):1-54.

2 Bateman ED, Reddel HK, Eriksson G, et al. Overall asthma control: the relationship between current control and future risk. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(3):600-608.

3 Dougherty RH, Fahy JV. Acute exacerbations of asthma: epidemiology, biology and the exacerbation-prone phenotype. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39(2):193-202.

4 Afessa B, Morales I, Cury JD. Clinical course and outcome of patients admitted to an ICU for status asthmaticus. Chest. 2001;120(5):1616-1621.

5 Pepe PE, Marini JJ. Occult positive end-expiratory pressure in mechanically ventilated patients with airflow obstruction: the auto-PEEP effect. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;126(1):166-170.

6 Corbridge T, Hall JB. The assessment and management of status asthmaticus in adults. State-of-the-art. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1995;151:1296-1316.

7 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Expert Panel Report 3. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. Available at. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/asthma/asthgdln.pdf, 2007.

8 McFadden ERJr. Acute severe asthma: state of the art. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2003;168(7):740-759.

9 Nowak R, Corbridge T, Brenner B. Noninvasive ventilation. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6(4):367-370.

10 Tuxen DV, Lane S. The effects of ventilatory pattern on hyperinflation, airway pressures, and circulation in mechanical ventilation of patients with severe air-flow obstruction. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;136(4):872-879.

11 Brenner B, Corbridge T, Kazzi A. Intubation and mechanical ventilation in the asthmatic patient in respiratory failure. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:371-379.

12 Williams TJ, Tuxen DV, Scheinkestel CD, Czarny D, Bowes G. Risk factors for morbidity in mechanically ventilated patients with acute severe asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146(3):607-615.

13 Krishnan JA, Nowak R, Davis SQ, Schatz M. Anti-inflammatory treatment after discharge home from the emergency department in adults with acute asthma. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6:380-385.

14 Schatz M, Rachelefsky G, Krishnan JA. Follow up-after acute asthma episodes: what improves outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(2 Suppl):S35-S42.

) to perfused (

) to perfused ( ) alveolar-capillary units. The severity of hypoxemia roughly tracks the severity of obstruction, but in recovering patients, airflow rates may improve faster than Pa

) alveolar-capillary units. The severity of hypoxemia roughly tracks the severity of obstruction, but in recovering patients, airflow rates may improve faster than Pa inequality, indicating that larger airways recover faster than smaller airways. Multiple inert gas elimination technique (MIGET) analysis also demonstrates small areas of high

inequality, indicating that larger airways recover faster than smaller airways. Multiple inert gas elimination technique (MIGET) analysis also demonstrates small areas of high  relative to

relative to  and slightly increased physiologic dead space in acute asthma. This may result from decreased blood flow to hyperinflated lung units. Elevated dead space and decreased minute ventilation in the critically hyperinflated and fatiguing patient underlie the development of hypercapnia in severe exacerbations.

and slightly increased physiologic dead space in acute asthma. This may result from decreased blood flow to hyperinflated lung units. Elevated dead space and decreased minute ventilation in the critically hyperinflated and fatiguing patient underlie the development of hypercapnia in severe exacerbations.

units. Oxygen saturation should be monitored until there is clear clinical progress, remembering that improved oxygenation may lag behind improved airflow rates.

units. Oxygen saturation should be monitored until there is clear clinical progress, remembering that improved oxygenation may lag behind improved airflow rates.