7 Settings of Care

In thinking about where your child will die, at home or in the hospital, you have to contemplate something that is utterly heartbreaking. Recognize that you are doing the hardest, most selfless, and most loving work a parent ever could do. Take credit for that.1

—Joanne Hilden and Daniel Tobben

This chapter explores the settings in which children with life-threatening conditions and their families receive palliative care. It is not uncommon that at different points in the illness trajectory, patients may be treated at different sites such as hospitals, home care facilities and agencies, chronic care facilities, with different teams of clinicians in each setting. Care also extends to respite, schools and other community venues where the children continue to live their lives. The medical home, as described by the American Academy of Pediatrics2 has particular relevance for these children. It is a model of delivering primary care that is accessible, continuous, comprehensive, family-centered, coordinated, compassionate, and culturally effective. The aim of the medical home is to support the needs of children in the home through collaboration among families, clinicians, and community providers. There are statewide initiatives for developing and implementing the medical home model throughout the country.

Epidemiological Factors in Death in Childhood

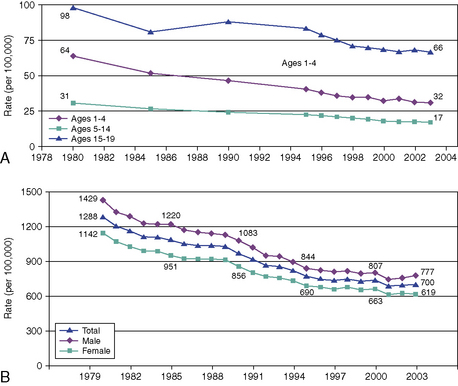

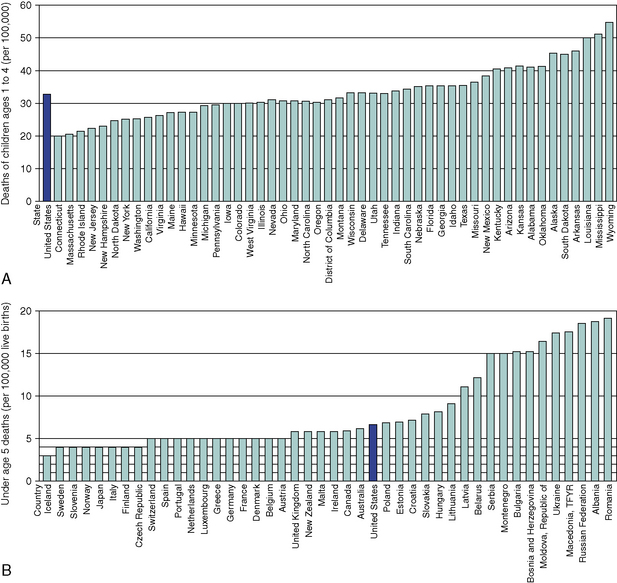

Despite significant advances in medicine, and the ensuing reduction in mortality rates in children over the past 25 years, children still die (Figs. 7-1 and 7-2). This is attributed to a number of improvements and advances in pediatric health care, including:

Fig. 7-2 A, Deaths of children, ages 1-4, by state. B, Under age 5 deaths, (by country, per 100,000).

(Data adapted from Field MJ and Behrman RE, eds. “Patterns of Childhood Deaths in America,” Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Press:2003, pp 41-71.)

A 2003 Institute of Medicine report3 estimates that there are approximately 55,000 deaths of children younger than 18 years per year, compared to more than 2 million adult deaths per year in the United States. Approximately, 51 percent of those children die in the first year of life (34 percent in the neonatal period and 17 percent from one month to 12 months of age), 10 percent from 1 year to 4 years of age, 14 percent from 5 years of age to 14 years, and 25 percent from 15 to 19 years of age. In addition there is a large group of young adults (ages 20 to 24), who succumb to chronic debilitating pediatric diseases.

The causes of death vary and are age-dependent: birth defects, low birth weight, maternal complications, respiratory distress, and sepsis account for the majority of deaths in the first year of life. Unintentional injuries, homicide, suicide, cancer, heart disease, and sudden infant death syndrome account for more than 51 percent of pediatric deaths. There still remains a large category of other causes, accounting for 18 percent of pediatric deaths.3

Conditions appropriate for pediatric palliative care fall into one of the following groups:

The Hospital

As children live for longer periods, the need for complex services also escalates.3,6–9 In addition to multiple visits to sub-specialty clinics, many of these children have prolonged and repeated hospital admissions. Whatever the nature and duration of the admission, hospitalization exerts extraordinary psychological demands. The child’s physical distress, and the parents’ witnessing of that distress, is compounded by the implications of the illness that necessitate hospitalization, and by the separation from normal life and from other family members, especially siblings or other children.10 Counterbalancing these stressors, particularly for children with illnesses who have required frequent and prolonged admissions, is the sense that the hospital clinicians become a second family who understand and share in the family’s experiences. Hospitals are a place where many children with life-threatening illnesses and families live, often for prolonged periods.

The Intensive Care Unit

The majority of children (more than 56 percent) die in hospitals and more than 85 percent of these deaths occur in the ICU.3,7 These ICU settings include neonatal (NICU), pediatric (PICU) and more recently created cardiovascular (CVICU) units. Exceptions include tertiary children’s hospitals with end-of-life programs that work collaboratively with community resources.11 A retrospective analysis of deaths in a Canadian tertiary care children’s hospital over a 21/2 year period studied children who were hospitalized for at least 24 hours prior to their deaths and those who were hospitalized for at least 7 days prior to their deaths.12 Acutely ill children who were previously healthy were excluded. Demographic data included age, gender, primary diagnosis, location of death, pain and symptom management, communication at end of life including CODE status, family preference for location of death, and the child’s involvement. Of the 236 deaths, only 86 met study criteria. Neonates accounted for 56 percent of the deaths; in 8, death was unexpected. The ICU saw 83 percent of the deaths and 78 percent of those children were intubated at the time of death. More than half, 57 percent, were medically paralyzed and 3 were on extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Opioids were administered, mostly by continuous infusion, in 84 percent of the children for pain, dyspnea, discomfort related to mechanical ventilation, or post-operative pain. Acetaminophen, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and complementary medications were also used, as well as non-pharmacologic therapy, including relaxation and imagery.

A retrospective analysis reviewed the hospital care required for 9000 children and young adults with complex chronic conditions (CCCs) during their last year.8 Children with these conditions accounted for one-fourth of all pediatric deaths. More than 84 percent were hospitalized at death and 50 percent received mechanical ventilation during their terminal admission. Neonates who were less than 7 days of age spent 92 percent of their lives in the hospital; those aged 7 to 28 days spent 85 percent; and infants between one month and 1 year of age spent 41 percent of their lives in the hospital. In the non-neonates, 55 percent were hospitalized at death, with 19 percent mechanically ventilated. The rate of hospital use increased overall as death approached.

This study8 also found variability as to whether children’s code and resuscitation status had been addressed. Discussion about code status was documented only for 79 percent of patients. Results demonstrated that multiple discussions with families were required regarding resuscitation and an actual Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order. Once a DNR decision was obtained, the majority of children died within one day, although some children lived as long as 30 days. In charts without documentation of DNR status, cardiopulmonary resuscitation was initiated but was unsuccessful.

The mode of death in a number of PICUs has been well described.13–18 A decision to forgo life-sustaining treatments was made in only 20 to 55 percent of critically ill children who eventually died. Diverse cultural, religious, philosophical, legal, and professional attitudes often affect these decisions. Despite the children’s grave prognoses, CPR was initiated and had a failure rate that varied from 16 percent to as high as 73 percent. Full life support at the time of death varied from 18 to 55 percent of the patients. A DNR order was found in less than 25 percent of the patient’s charts. Withdrawal or limitation of life-sustaining therapy, including extubation, occurred in 43 percent of the patients. More than 90 percent of these children died within 24 hours; the rest died on the second day.

The Intensivist’s Role

The intensivist must engage the family in ongoing discussions about end-of-life issues and repeatedly address and evaluate the goals of care.5 This role continues long after decisions to forgo life-sustaining treatments have occurred, as families look to the attending intensivist throughout the dying process. The ICU team assures the family that the child’s care is undertaken with a focus on quality of life, dignity, and comfort.19,20 The ICU nurses play a central role; at the bedside, families often call upon them for explanations of the child’s care and the existing options as well for emotional sharing.21 This is also where the social workers, psychologists, child life specialists, and chaplains of the interdisciplinary team can play pivotal roles. Studies have shown that when the ICU staff spends time conversing and providing bereavement resources, the families experience less stress, anxiety, and depression after the child’s death.22

Decision-Making in the ICU Setting

The decision-making process is often extremely difficult and may require many meetings and interdisciplinary care conferences with the family. The process may be divided into three steps: deliberation, eventually leading to the decision and goal setting; implementation; and evaluation of the decision and its application.23–25 During the deliberation, the family’s decision makers and the clinical teams must weigh the benefits and burdens of various options in terms of survival, long-term outcomes, and quality of life for the child. The concept of shared decision making allows for a consensus to be reached by all active participants once the pertinent information has been shared. It should enable the family to make a truly informed consent.

Cardio-pulmonary resuscitation

The use of cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) has had enormous impact on children’s care. Unfortunately, providing CPR for both acutely and terminally ill patients is not as beneficial as had been hoped, because less than 27 percent of children who arrest in the hospital survive to discharge. Some advocate CPR should be reserved only for those children with truly reversible medical conditions.26 Nonetheless, with the use of more invasive procedures in critical care, more children may be resuscitated onto an ECMO circuit following a cardio-pulmonary arrest. This intervention may indeed improve survival, but is associated with the high risk of neurologic injury.27,28 Clinicians should inform families about the risks and benefits of CPR. It is also crucial that the family be reassured that a Do Not Resuscitate order does not mean the cessation of care for the child. Rather, it indicates a shift in priorities, toward the implementation of more comfort interventions for the child.29–31

Withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining support

The decision to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment is always difficult. While they are considered to be ethically equivalent, physicians seem to be more comfortable with withholding; withdrawing may increase a sense of responsibility for a patient’s death. The minimizing and eventual withdrawal of technology increases opportunities for the family to hold the child. Parents may hold and cuddle their child, or lie in bed and comfort the child during this transitional period. The process of withdrawal of technological intervention requires a team effort and an environment that is supportive for the family. A room that provides privacy for the family, while also shielding other patients and families in the intensive care unit, is beneficial.5,13,32,33

Compassionate extubation

Families’ questions about what to expect when a terminal, or compassionate, extubation is planned revolve around whether the child will feel pain or suffer, be conscious, or breathe. Liberal use of sedatives, analgesics, and anxiolytics should prevent most negative symptoms. Families must be prepared for different scenarios that could unfold; however, no sure predictions can nor should be made regarding when their child will die. Certain children will die shortly after extubation, including those who are brain dead, in severe refractory shock, or in severe respiratory failure with refractory hypercarbia and hypoxia. Children who are not brain dead may linger for hours, days or longer, with variable respiratory patterns. If the parents or nurses perceive the child to be uncomfortable, then opioids and/or benzodiazepines should be given; for children who are difficult to sedate, propofol or pentobarbital may be used. Pain and suffering should be treated aggressively, even if this results in a foreseen unintended hastening of death. This principle is referred to as the “doctrine of double effect.”33–35

Withholding or withdrawing medically provided nutrition and hydration

Although not a frequent issue in the ICU, pediatricians often have a difficult time with this aspect of terminal care and benefit from team discussion. Arguments that have been made for continued hydration and nutritional support are that children have a remarkable ability to recover, infants need assistance with feedings, and very little is known about whether or not a child at the end of life willfully refuses food and water. The American Academy of Pediatrics concluded in 2009 that the withdrawal of medically administered fluids and nutrition for pediatric patients is ethically acceptable in certain circumstances.19

Autopsy

Although it is often difficult to request an autopsy, it may provide the parents and clinicians with more information about the child’s illness and death. An autopsy may be all-inclusive or limited to those organs most involved in the disease process. Many clinicians have found the request for autopsy to be more successful if the subject is broached during end-of-life discussions with the family before the child has died. Parents may be too distraught to consent if they are approached for the first time in the immediate aftermath of the child’s death. When an autopsy is performed, it is imperative that one of the physicians who cared for the child review the results with the parents when they feel emotionally ready.36 In addition to providing information, this meeting provides a valuable opportunity for follow-up with the family. If the death is a coroner’s case, then the coroner will make the determination about the post-mortem exam and the potential for organ and tissue donation.

Organ and tissue donation

Most ICUs work closely with an Organ Procurement Organization (OPO), whose professionals are trained to counsel families. In the past, brain death criteria had to be met in order to be a donor. Now, all hospitals must have a Donation after Cardiac Death (DCD) policy. This allows organs to be donated after life-sustaining interventions are discontinued, even when criteria for brain death have not been met. In these instances, it is anticipated that the patient will have a cardiac death within 2 hours in the operating room, and then have the appropriate organs retrieved for transplantation. Although the procedure is designed to increase the number of organs available, it is a cumbersome process and involves many additional steps and significant waiting times. If the patient does not sustain a cardiac death in the requisite time for donation, the child must be returned to the ICU or another in-patient area for ongoing care.32–34

Emergency Medical Services

Unintentional injury remains the leading cause of mortality among children age 1 to 19 years, accounting for 44 percent of deaths.40,41 Thus, from an epidemiologic perspective, the dominant trajectory of childhood death is sudden and unexpected.42 An estimated 20 percent of childhood deaths actually occur in the emergency medical services (EMS) environment.43,44 Myriad pediatric palliative care issues face clinicians in the EMS, a setting where all trajectories of pediatric life-threatening conditions may intersect. As a result of biomedical, procedural and technologic advances, many children with complications of prematurity, congenital malformations, complex chronic, and life-threatening diseases are surviving longer and living in community-based settings such as sub-acute care facilities or at home. Physiologic exacerbation of an underlying disease state, intermittent infection risk and/or mechanical complications of technology dependence all require immediate attention, and present a spectrum of palliative care challenges to staff. This section will focus on sudden and unexpected death in childhood, and elucidate:

Organization of emergency medical services for children

EMSC are organized around the premise that childhood is a relatively healthy time of life and that the death of a child is a relatively rare event. The overwhelming majority of children who present for emergency care are initially seen close to home at community hospital emergency departments (EDs). Only 3 percent of seriously ill or injured children initially present to pediatric tertiary, critical care, or trauma centers.45,46 More so than for adults, EMSC are highly regionalized, with scarce subspecialty and multidisciplinary services strategically concentrated in a hub-and-spoke wheel model in population centers. The more extensive the anatomic or physiologic derangement and the higher the clinical acuity, the greater is the need for care of the child to flow centrally to the hub. Especially for life- or limb-threatening conditions of sudden and unexpected onset, the goal is to get the right patient to the right place in the right time. This often necessitates bypassing local community resources to access more sophisticated levels of care. The EMSC system is an integrated continuum of care model, such that patient care flows seamlessly from the local community response through pre-hospital transport and on to hospital-based definitive care (Fig. 7-3). Implementation of this model necessitates a minimum level of expertise and readiness by multiple professionals, including basic emergency medical technicians, paramedics, nurses, and physicians at every step to ensure that timely and appropriate care is rendered.

Among the unique challenges of such an approach are:

Family-centered care

A growing body of evidence attests to the benefits of family-centered care in the ED. Such an approach focuses on effective, culturally sensitive communication and close interaction with parents.47 A number of institutions have formally incorporated practices for parental presence during invasive procedures, even when a child is in full arrest and requires resuscitation in a code room or trauma bay. Family presence involves their attendance in a location that affords visual or physical contact with the patient. This topic has generated strong debate. The most compelling and frequently cited argument against family presence is based on surveys that presented a hypothetical situation. Respondents thought that the event might be so traumatic that families could lose emotional control, and as a result compromise the functioning of the medical team and the care of the child. Another issue that emerged is providers’ fears that family presence could intensify the risk of litigation, unsettle clinicians such that their technical skills would decline, and infringe upon the patient’s confidentiality and privacy rights. However, no evidence exists to support any of those arguments.48 Thus the time-honored practice of banning families from the bedside during resuscitation and other emergency procedures appears to be grounded in tradition, rather than in evidence of beneficial or adverse outcomes.

The Community

Transitioning the child from the acute care setting to the community involves challenges not only for the child and family, but also for the clinical team and the institution. The decision to leave the hospital and receive care at home usually reflects a shift in treatment from life-prolonging therapy to comfort measures and quality of life.1 This change requires advanced planning and coordination of care amongst many stakeholders: the family, the hospital team, the hospice home care team, and the third-party payer. It is essential that one member of the team be identified as a coordinator, that a social worker or case manager participate in the discussion, and that a well-organized plan for care and communication be in place.49 Additionally, in finalizing the discharge plans, it is extremely beneficial to have representation from the community-based agency and, when possible, the third-party payer. The effort to include these stakeholders upfront is well worth the end result of smooth coordination. The team must advocate that:

The team must facilitate conversation with the family to dispel their fears and misconceptions about hospice, particularly their sense of taking their child home to die and giving up hope.1 While their child may ultimately die at home, families need reassurance that the focus is to maximize the quality of their child’s life and provide all possible comfort measures. They also need to know that returning to the hospital is always an option. This entails having a plan for a seamless transition back to the hospital should that become preferable or advisable.

Home-Based Hospice Services

In the United States, the most common setting for providing palliative care to children in the community occurs through hospice-based home-care programs. The majority of children die in hospitals, except where tertiary children’s hospitals have palliative care programs that work collaboratively with community resources.11 Although some adult hospices and programs have an interest and willingness to care for pediatric patients, adult-focused programs and staff are typically unprepared to respond to infrequent pediatric referrals and also lack connections to pediatric providers to assist them in providing safe, appropriate hospice care.50

Adult hospices vary in the amount of experience staff has had with children.1 One study indicated that of the palliative and hospice programs in the United States that admit children, 40 percent care for an average of 3 or fewer children per year.51 The Children’s Project on Palliative/Hospice Services (ChiPPS) conducted a survey of the more than 3,000 hospice programs in the United States in 2001. These results showed that only 450, or 15 percent, of those hospices surveyed indicated that they were prepared to offer hospice services to children.52 In a 2005 report from The National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO), it is noted that of the 4,100 hospice and palliative care programs in the United States that year, only about 738, or 18 percent, provided any pediatric services.53

Many physicians are unaware of or uncomfortable with the specialized services that pediatric hospice and palliative care programs can provide and thus are reluctant to make referrals.54,55 Inadequate training in pediatric palliative care56–59 can in turn have clinical ramifications in the children and may not receive services that would enhance their quality of life. Parents whose child had died at home with palliative or hospice care reported a calm and peaceful last month of life.58

There are practical steps to facilitate the process of transitioning the child to the home. Acquiring information about the hospice home care agencies in the family’s area is essential prior to the transition (Box 7-1, 7-2).

BOX 7-1 Evaluating Home Hospice Agencies

Carroll JM, Torkildson C, Winsness JS. Issues related to providing quality pediatric palliative care in the community. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007 Oct;54(5):813-827, xiii.

Information to obtain from home hospice agencies when considering referral of a child

BOX 7-2 Guidelines for Coordinating Community-Based Palliative and Hospice Services

Free-Standing Palliative and Respite Care Facilities

The concept of respite care59 is to provide temporary relief or rest to the caregivers of the seriously ill child, either in or outside the home, whether for hours or weeks at a time. Respite care is designed to give parents and other caregivers the opportunity to recharge their batteries so that they can better manage the challenges of caring for the child. Respite care may be offered voluntarily or on a fee-for-service basis, as a benefit with some insurance plans. A case manager or care coordinator can assist the family in accessing this essential service.

School

Appreciating the context of the child’s life, understanding what makes it meaningful, and respecting the relationships that are central to it are essential.60 For the child who wishes to attend school, many crucial issues must be considered in preparation. Does the school have a nurse or other designated personnel available to accommodate the child’s medical needs? Is there a need for an out-of-hospital DNR order? What is the plan for managing issues in the child’s care that might arise during the school day? What is the responsibility of the administration to the other students regarding the possibility of a child dying at school? Frequently parents decide that it is easier to have their child home-schooled rather than deal with these many and often controversial issues. However, under the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (Public Law 94-142), all children are guaranteed the right to be in the classroom. The question of “What is in the best interest of the individual child?” must be balanced against the interests of others in the situation, such as the school community.

In 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Committees on Bioethics and School Health issued the policy statement that “parents have a legal right to forego cardiopulmonary resuscitation and to ask the school to respect that decision.” Rushton60 says DNR orders are simply an extension of the right of families to make decisions about medical treatment or non-treatment. However, school officials argue that medically untrained staff may misinterpret a DNR order, thereby doing more harm than good for the child. Administrators are concerned that failing to act could make the school and/or school district liable.

The DNR order is usually honored without reservation in the hospital or hospice setting, but is rarely supported for children in school or other community settings. Although 43 out of 50 states and the District of Columbia have enacted out-of-hospital DNR orders, only five would extend legal protection to school personnel for honoring such decisions.61 Only 17 of these states and D.C. permit advance healthcare decisions for minors. These ill-defined laws obviously create problems for parents and legal guardians of children who choose to attend school.

Reimbursement Issues

The reasons for woeful treatment of dying children and grieving families is due in large part to the healthcare system’s inability to recognize the need for palliative care even when children are receiving curative care.62

A significant barrier is that state Medicaid hospice benefits are based on the federal Medicare model. Hospice eligibility criteria restrict care to individuals who will die within six months. Furthermore, concurrent treatment to prolong life cannot be pursued while receiving palliative care. Additionally, within the 2010 regulations and reimbursement structure, families risk the loss of benefits such as dietary supplements or skilled home nursing care if they accept hospice. These criteria prevent families and clinicians from integrating both aspects of care.63 It is also important to note that private insurers model their hospice benefits along Medicare guidelines. There are multiple payers and financial sources for pediatric palliative care, versus one payer source, Medicare, for adult palliative care.

The Institute of Medicine report1 states: “Approximately two-thirds of children are covered by employment-based or other private health insurance; about one-fifth are covered by state Medicaid or other public programs, but some 14 to 15 percent of children under age 19 have no health insurance.” Some of these uninsured children receive services based on safety-net providers, grants, or private donations. However, there remain children who do not receive necessary services. The IOM report further states that “for insured children and families, coverage limitations, provider payment methods and rules, and administrative practices can discourage timely and full communication between clinicians and families and restrict access to effective palliative and end-of-life care.”

The IOM also warns that the hospice healthcare delivery model for adults and children in 2010 can create “incentives for under treatment, overtreatment, inappropriate transitions between settings of care, inadequate coordination of care, and poor overall quality of care.”3

In an effort to counterbalance the inequities created by the Medicare hospice model, Children’s Hospice International (CHI) developed the Program for All-Inclusive Care for Children (PACC) and their Families. This program provides an alternative to the existing barriers regarding referral and reimbursement to obtaining palliative care for children. The PACC model is an innovative program, which provides access to care for all children diagnosed with life-threatening conditions. It allows for reimbursement by all payers including private insurance, workplace coverage, managed care, and Medicaid. CHI PACC permits states to receive federal reimbursement for more coordinated services than are usually provided under Medicaid.64

Congressional appropriations through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) initially funded pilot programs in Colorado, Florida, Kentucky, New York, New England, Utah, and Virginia.64,65 Florida and Colorado have been fully approved for CMS waivers.65–67 Florida received its waiver approval in July 2005 for a 5-year, statewide demonstration project of the PACC program.66 In January 2007, Colorado received approval of their request for a CMS waiver. They will implement a 3-year renewable demonstration project for pediatric palliative care.67 Based on legislation mandated in the fall of 2006, California began a 3-year pilot program in 2009 under the Children’s Hospice and Palliative Care waiver.68 Other states interested in implementing CHI PACC and are submitting requests for waivers include Arkansas, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia.64 The myriad issues that surround reimbursement for palliative and end-of-life care, both for adults and children, are trigger topics for challenge and reform.

Summary

At the diagnosis of a life-threatening condition, it is important to offer an integrated model of palliative care that continues throughout the course of illness, regardless of outcome.63

1 Hilden J., Tobin D. Shelter from the storm: caring for a child with a life-threatening condition. Cambridge: Perseus, 2003;164.

2 American Academy of Pediatrics. AAP National Center of Medical Home Initiatives for Children with Special Needs. 2010. www.medicalhomeinfo.org/. Accessed January 19

3 Field M.J., Behrman R.E., editors. Patterns of childhood death in America, Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003. the National Academy of Press. 41-71.

4 ACT (Association for Children with Life-threatening and Terminal Conditions and their Families), National Council for Hospice and Specialist Palliative Care Services and SPAPCC (Scottish Partnership Agency for Palliative and Cancer Care). Palliative care for young people: ages 13–24. 2001. London

5 Frankel L.R. Pediatric palliative care: the role of the intensivist, current concepts in pediatric critical care. Soc Crit Care Med. 2007:103-110.

6 Sourkes B., Frankel L.R., Brown M., et al. Food, toys, and love: pediatric palliative care. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2005;35:350-386.

7 Feudtner C., Feinstein J.A., Satchell M., et al. Shifting place of death among children with complex chronic conditions in the United States, 1989–2003. JAMA. 2007;297:2725-2732.

8 Feudtner C., DiGiuseppe D.L., Neff J.M. Hospital care for children and young adults in the last year of life: a population-based study. BMC Med. 2003;1:1-9.

9 Liben S., Lissauer T. Intensive care units. In: Goldman A., Hain R., Liben S., editors. Oxford textbook for palliative care for children. Oxford University Press; 2006:549-556.

10 Sourkes B. Armfuls of time: the psychological experience of the child with a life-threatening illness. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995.

11 National Center for Health Statistics: www.cdc.gov/nchs/. Accessed May 4, 2010.

12 McCallum D.E., Byrne P., Bruera E. How children die in hospital. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;20:417-423.

13 Devictor D., Latour J.M., Tissieres P. Forgoing life-sustaining or death-prolonging therapy in the pediatric ICU. Pediatr Clin North Am. 55:3; 2008: 791-804.

14 Burns J.P., Mitchell C., Outwater K.M., et al. End-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit after the forgoing of life-sustaining treatment. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(8):3060-3066.

15 Devictor D.J., Nguyen D.T. Forgoing life-sustaining treatments; how the decision is made in French pediatric intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1356-1359.

16 Garros D., Rosychuk R.J., Cox P.N. Circumstances surrounding end of life in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2003;112(5):e371.

17 Althabe M., Cardigni G., Vassallo J.C., et al. Dying in the intensive care unit: collaborative multicenter study about forgoing life-sustaining treatments in Argentine pediatric intensive care units. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2003;4(2):163-169.

18 Zawistowski C.A., DeVita M.A. A descriptive study of children dying in the pediatric intensive care unit after withdrawal of life sustaining treatment. Pediat Crit Care Med. 2004;6(3):258-263.

19 Diekema D.S., Botkin J.R. Clinical report: forgoing medically provided nutrition and hydration in children. Pediatrics. 2009;124:813-822.

20 Riling D.A., Hofmann K.H., Deshler J. Family-centered care in the pediatric intensive care unit. ed 3. In Fuhrman B., Zimmeran J., editors. Pediatric critical care. 2006. Mosby Elsevier: Philadelphia: 106–116

21 Latour J.M., Haines C. Families in the ICU: do we truly consider their needs, experiences and satisfaction? Nurs Crit Care. 2007;12(4):173-174.

22 Hov R., Hedelin B., Athlin E. Being an intensive care nurse related to questions of withholding or withdrawing curative treatment. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16(1):203-211.

23 Burns J.P., Rushton C.H. End-of-life in the pediatric intensive care unit: research review and recommendations. Crit Care Clin. 2004;20(3):467-485.

24 Solomon M.Z., Sellers D.E., Heller K.S., et al. New and lingering controversies in pediatric end-of-life care. Pediatrics. 2005;116(4):872-883.

25 Sharman M., Meert K., Sarnaik A. What influences parents’ decisions to limit or withdraw life support? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(5):513-518.

26 Ralston M., Hazinski M.F., Zaritsky A.L., et al. PALS Provider Manual. American Heart Association. 2006:3.

27 Tajik M., Cardarelli M.G. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation after cardiac arrest in children: what do we know? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:409-417.

28 Barrett C.S., Bratton S.L., Salvin J.W., et al. Neurological injury after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation use to aid pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10(4):445-451.

29 Levy M., Curtis R. Improving end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(Suppl):S301.

30 Truog R.D., Meyer E.D. Toward interventions to improve end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(Suppl):S3739.

31 Morrison W., Berkowitz I. Do not attempt resuscitation orders in pediatrics. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(5):757-771.

32 Mathers L.H., Whitney S.N. Letting go: a study in pediatric life-and-death decision-making. In: Frankel L.R., Goldwirth A., Rorty M.V., Silverman W.A., editors. Ethical dilemmas in pediatrics. Cambridge: Cambridge Univeristy Press; 2005:89-112.

33 Munson D. Withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in pediatric and neonatal intensive care units. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(5):773-785.

34 Frankel L.R., Randle C.J., Goldwirth A. Complexities in the management of a brain-dead child. In: Frankel L.R., Goldwirth A., Rorty M.V., Silverman W.A., editors. Ethical dilemmas in pediatrics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005:135-155.

35 Davidson J.E., Powers K., Hedayat K.M., et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(2):605-622.

36 Riggs D., Weibley R.E. Autopsies and the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1994;41(6):1383-1393.

37 Antommaria A.H., Trotochaud K., Kinlaw K., et al. Policies on donation after cardiac death at children’s hospitals: a mixed-methods analysis of variation. JAMA. 2009;301(18):1902-1908.

38 Pleacher K.M., Roach E.S., Van der Werf W., et al. Impact of a pediatric donation after cardiac death program. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10(2):166-170.

39 Hamilton T.E. Improving organ transplantation in the United States: a regulatory perspective. Am J Transplant. 2008;8:2503-2505.

40 Heron M., Sutton P.D., Xu J., et al. Annual summary of vital statistics. Pediatrics. 2010;125:4-15.

41 Michelson K.N., Steinhorn D.M. Pediatric end-of-life issues and palliative care. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2007;8:212-219.

42 Lunney J.R., Lynn J., Foley D.J., et al. Patterns of functional death at the end of life. JAMA. 2003;289:2387-2392.

43 Wright J., Johns C., Joseph J. End-of-life care in EMS for children. In: Field M., et al, editors. When children die, Institute of Medicine. Washington: National Academy Press; 2003:580-589.

44 Knapp J., Mulligan-Smith D., the Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Death of a child in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1432-1437.

45 Wright J., Krug S. Emergency Medical services for children. In Kliegman R., et al, editors: Nelson textbook of pediatrics, ed 19, Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2010. (in press).

46 Gausche-Hill M., Krug S., the AAP ED Preparedness Guidelines Advisory Council. Guidelines for Care of Children in the ED—Policy Statement. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1233-1243.

47 O’Malley P.J., Brown K., the Committee on Pediatric Emergency Medicine. Patient and family-centered care of children in the emergency department: technical report. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e511-e521.

48 Guzzetta C., Clark A., Wright J. Family presence in emergency medical services for children. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2006;7:15-24.

49 Kang T., Hoehn S., Licht D., et al. Pediatric palliative, end-of-life and bereavement care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:1029-1046.

50 Sumner L. Pediatric care: the hospice perspective. In: Ferrell B., Coyle N., editors. Textbook of Palliative Nursing. ed 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006:916.

51 Maxwell T., Reifsnyder J., Davis C., et al. Our littlest patients: a national description of pediatric hospice patients. 2006. Paper presented at the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine annual assembly. Nashville, Tenn,

52 Levetown M., Barnard M., Hellston M., et al. A call for change: recommendations to improve the care of children living with life-threatening conditions. Alexandria, Va: NHPCO, 2001. A white paper produced by the Children’s International Project on Palliative/Hospice Services (ChIPPS) Administrative/Policy workgroup of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization

53 National data set—NHPCO’s facts and figures 2005 findings. NHPCO, 2006.

54 Carroll J.M., Torkildson C., Winsness J.S. Issues related to providing quality pediatric palliative care in the community. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(5):813-827.

55 Armstrong-Daily A, Zarbock S, editors. Hospice care for children, ed 3 New York, 2008, Oxford University.

56 Contro N.A., Larson J., Scofield S., et al. Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1248-1252.

57 Drake R., Frost J., Collins J.J. The symptoms of dying children. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;26(1):594-603.

58 Wolfe J., Grier H.E., Klar N., et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):326-333.

59 American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on bioethics and committee on hospital care: palliative care for children. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2 Pt 1):351-357.

60 Rushton C.H., Will J.C., Murray M.G. To honor and obey: DNR orders and the school. Pediatr Nurs. 1994;20(6):581-585.

61 Kimberly M.B., Forte A.L., Carroll J.M., Feudtner C. Pediatric do-not-attempt-resuscitation orders and public schools: a national assessment of policies and laws. Am J Bioeth. 2005.

62 Texas Cancer Council. End-of-life care for children. Houston: Texas Children’s Cancer Center, Texas Children’s Hospital, 2000.

63 AAP. Palliative care for children. Pediatrics. 2000;106(2):351-357.

64 Children’s Hospice International program for all-inclusive care for children and their families (CHI PACC). 2009. www.chionline.org/programs/.. Accessed July 30

65 CHI. CHI PACC model: The Colorado, Florida, Kentucky, Utah and New York experience. Children’s Hospice International. 2010. www.chionline.org/programs/. Accessed May 4

66 The Florida CHI PACC model: partners in care, together for kids. 2010. www.chionline.org/states/fl.php. Accessed May 4

67 The butterfly program: a Children’s Hospice International program for all-inclusive care for children and their families (CHI PACC). www.chionline.org/states/co, 2010. Accessed May 4.

68 The Nick Snow Children’s Hospice & Palliative Care Act of 2006— Assembly Bill 1745. 2010. http://childrenshospice.org/coalition/ab-1745-the- nick-snow-childrens-hospice-palliative-care-act-of-2006/. Accessed May 4