Chapter 2 Setting Up an Endoscopy Facility

Introduction

The safe and efficient performance of gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy has the following requirements:1

A properly trained endoscopist2 with appropriate privileges to perform specific GI endoscopic procedures3,4

A properly trained endoscopist2 with appropriate privileges to perform specific GI endoscopic procedures3,4 Adequately designed and equipped space for patient preparation, performance of procedures, and patient recovery

Adequately designed and equipped space for patient preparation, performance of procedures, and patient recoveryMany of the above-listed requirements for safe and efficient GI endoscopy depend on the careful development of endoscopy areas—specifically the setting up or planning and design of an endoscopy facility. This chapter describes that process, beginning with laying the groundwork, including the development of a business plan and review of regulatory issues; site selection; facility planning and design, including patient flow and space needs; equipment requirements; staffing needs; and scheduling considerations. Some additional issues, such as endoscope cleaning and storage, tissue specimen processing and handling, record keeping and documentation, and quality assurance and improvement, are discussed briefly but are covered in more detail in subsequent chapters of this book (see Chapters 4, 5, and 9).

Exploring Possibilities

Type of Facility

The decision regarding which type of facility to establish is affected by the practice environment (solo practitioner, small or large group, single-specialty or multispecialty group, independent or hospital-based) and local economics and politics. Regardless of the service location, high quality must be maintained. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) has stated that the “standards for out-of-hospital endoscopic practice should be identical to those recognized guidelines followed in the hospital.”1 In an insurance-based environment, the hospital-based unit poses the fewest financial risks and demands for the endoscopist during the early phases of operation, and its use avoids alienating hospital administration by preserving hospital case volume. The hospital-based unit affords the endoscopist little control over operations, however, and offers him or her the lowest total financial return. Office endoscopy offers control and convenience with better financial return for the physician, but it poses some safety and liability concerns.8,9 A single-specialty endoscopic ambulatory surgery center (EASC) provides the best of control, efficiency, convenience, and reimbursement for the physician owners and is extremely popular with patients, referring physicians, and payers.10,11 At the time of this writing, a major ASC payment reform is being implemented by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which is resulting in drastic cuts of facility payments for endoscopic services. How this reform will affect efforts to provide beneficial GI services to patients at a reasonable cost remains to be seen. More information about this payment reform is available elsewhere.12 Regardless of the type of facility being developed, formulating a business plan and understanding various regulatory issues are usually the first steps in the process.

Business Plan

The decision to set up an endoscopy facility should be made only after detailed data gathering and the formulation of a business plan (e.g., market analysis, financial pro forma, implementation time line).13–15 For a hospital-based unit or academic medical center, facility planners and accountants often perform these functions. For an office-based suite or an EASC, the tasks fall to the physician owners, aided by numerous consultants, contractors, or corporate partners. Even with skilled help, however, development of an accurate and reliable business plan and pro forma are highly dependent on physician estimates, insights, and work habits. Physician input into the business plan makes the difference between a perfunctory exercise and an accurate predictor of future performance. Endoscopy facilities represent small to medium-sized investments requiring substantial financial resources and staff. Procedure volume must be sufficient to produce adequate revenue to cover the costs of building and running the facility and to generate a profit on investment. Generally, three or four busy endoscopists performing 1200 to 1800 total procedures per year are required to offset the financial risk of the facility.16

Many factors influence the financial performance of an endoscopy facility, including initial investment, expected volumes of service, revenue per unit of service, fixed operating costs, and variable costs per unit of service. The initial investment includes the cost of construction, equipment, and working capital for the first few months of operation. Strategic planning is important to anticipate group growth and demand for services in the coming 5 to 10 years.13,15 The impact of managed care plans or other major health plans on the practice must also be anticipated. In addition, competition, new technology, population changes, and demographics might affect case volume for the practice and the endoscopy facility.

A pro forma is a calculation examining the financial feasibility of a project based on anticipated investment and operating costs and revenues. The purpose of the pro forma is to predict reliably cash flows and profitability for the project. Initial investment costs have been defined previously. Also incorporated in the pro forma are estimated total costs per case based on estimated fixed and variable costs and expected case volume. Fixed costs are costs that remain constant regardless of the number of procedures performed and include rent, interest, depreciation, taxes, insurance, amortization, and management fees. Variable costs, which account for the largest component of the average cost per case, include salaries and benefits, medical supplies, medications, equipment, maintenance and repair, administrative supplies, utilities, and accounting and legal fees. Break-even volumes can be determined by subtracting the variable expense per procedure from the average payment per procedure to indicate the contribution available to be used for overhead and profit. Dividing fixed costs by the contribution margin per procedure indicates the number of procedures needed to pay the fixed costs, also known as the break-even point. Additional service units above that level constitute profit. Vicari and Garry13 provided a simple example of a pro forma. The business plan and pro forma are mandatory in assessing the financial feasibility of the proposed endoscopy unit before construction. They further aid discussions in obtaining financing and help the architect design the unit for anticipated volumes.

Regulatory and Certification Issues

Before planning and designing the facility, one must understand the relevant regulatory and certification issues. As with the business plan, units developed in a hospital or academic medical center usually benefit from administrators and planners familiar with these complex issues. Physician owners of an office endoscopy suite or EASC must gain their own understanding. Various agencies provide myriad rules and regulations concerning endoscopy facilities.17–23 Legislation can come from federal, state, or local authorities. Regulations may come from federal agencies, state departments of health, and third-party accreditation organizations and private payers. Although these rules and regulations can seem excessive and needlessly costly, their intent is to ensure safe and successful outcomes for patients. Regulations and certification issues for endoscopy facilities can be divided into six main categories, as follows:17

Medicare Certification

Medicare certification is usually sought after obtaining state licensure and is required for any facility seeking reimbursement for Medicare and Medicaid work. Medicare regulations and requirements are usually more extensive than regulations of the state and address governance of the facility, transfer agreements with a nearby hospital, continuous quality improvement activities, Medicare architectural requirements, and medical records. Additional standards concern organization and staffing, administration of drugs, and procurement of laboratory and radiology services. Two other requirements warrant special attention as they relate to EASCs. First, the facility must be used exclusively for providing “surgical” services, a definition that includes GI endoscopies. This requirement mandates a separation from other health care activities, separate staffing, and maintenance of special medical and financial records. Finally, the facility must comply with state licensure laws,20 which is potentially difficult in some states because of restrictive CON requirements.

Payer Requirements

Individual health plans or insurers may have their own requirements, and these may vary significantly from payer to payer. Careful attention to local payer mix and any special requirements is necessary before designing and building an endoscopy facility to ensure qualification for payment. As outlined previously, the regulatory and certification issues for endoscopy facilities are “complex, detailed, and broad.”17 Any physician wishing to develop an endoscopy facility must understand these rules of regulation and certification. Appropriate legal counsel should be considered essential.

Facility Planning and Design

After forming a realistic business plan and acquiring an understanding of relevant regulatory and certification issues, attention turns to the planning and design of the facility. Although the remainder of this chapter includes some remarks about issues specifically related to hospital units, the main focus of the discussion is on the development of an outpatient endoscopy facility, details of which are equally applicable to hospital units. Objectives must be articulated to the design professionals to ensure that the facility meets the needs of patients, endoscopists, and staff. Some points to keep in mind are the following:24

If questions arise about the size or shape of a space, lay it out with tape on the floor and simulate work practices.

If questions arise about the size or shape of a space, lay it out with tape on the floor and simulate work practices.Although the physician representative, designated staff persons, architect, and contractor compose the major elements of the planning and design team, additional input may be needed from a mechanical engineer, electrical engineer, telephone contractor, information technology expert, and attorney.25 Consideration might also be given to involving a layperson or “patient” to ensure sufficient attention to issues of patient comfort, dignity, and privacy.

Planning

Scope of Activities

The first consideration is which endoscopic procedures and other services will be performed in the facility.19 The type of facility will, to a great extent, answer this question. For a hospital unit that must provide a wide range of endoscopic services, one or more rooms must be large enough and appropriately equipped to accommodate the special equipment required for complex procedures (e.g., endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography [ERCP], endoscopic ultrasound [EUS], balloon enteroscopy, laparoscopy, anesthesia cart). In some community hospitals, endoscopy units are shared with other specialties, such as cardiology or pulmonology, and have to accommodate procedures such as transesophageal echocardiography or bronchoscopy. If the hospital is part of an academic medical center, the unit may serve additional purposes, including teaching and research, requiring further modifications in space, equipment, and staffing.

The question sometimes arises whether it is better to have a multispecialty or single-specialty ASC. From the standpoint of services offered and equipment, a single-specialty EASC has the advantage of being the “focus factory.”27,28 In this environment, endoscopists, skilled GI nurses, and administrative staff maximally use equipment of relatively low cost, performing predictably timed procedures with a rapid turnaround. A single-specialty EASC avoids the problem of a multispecialty facility in which highly specialized equipment lies idle much of the time while physicians from differing specialties are performing their individual procedures.

Equipment

The greatest capital expense after the basic construction is equipment. Some tabulation of the equipment needed is necessary in the early planning stages and facility design. The basic equipment needed for an endoscopy unit is listed in Box 2.1.1,26,29 A detailed discussion of individual items is not presented here, but a few points are useful in integrating the equipment needs into planning and design. Generally, examining or procedure tables have been replaced by height-adjustable, rolling procedural stretcher carts that allow patients, once properly gowned for endoscopy, to mount the movable cart and not leave it until ready to leave the facility. These useful carts allow patients to be shuttled from preparation areas to procedure rooms and back to recovery areas and serve as procedure tables. This capability is very important to overall system efficiency and adds to patient safety by avoiding transfer to and from a procedure table.

Box 2.1

Endoscopy Facility Equipment List

Another major determinant of overall system speed and efficiency is the availability of endoscopes. Adequate numbers of endoscopes, high-level disinfection systems (“scope washers”), and adequate storage for extra endoscopes are required. Adequate numbers of endoscopes must be available to prevent inefficient downtime in the unit. In most endoscopy suites, variable costs account for 80% or more of the total costs of providing endoscopic services, and 50% to 60% of this is attributable to staff salaries, wages, and benefits.14 It is inefficient and fiscally unwise to have highly paid physicians and staff waiting for endoscopes. One of the most efficient scenarios is for one endoscopist to work out of two rooms so that he or she can move from room to room without major downtime. This scenario typically requires that each unit have three colonoscopes and three upper endoscopes for every two rooms in the facility. This allows two rooms always to be equipped for either upper endoscopy or colonoscopy with one endoscope always available to restock the next room during turnaround.

The luxury of additional endoscopes per two rooms allows for the inevitable loss of an endoscope resulting from breakage and repair time. A high-volume, efficient endoscopy unit cannot afford to be penny wise and endoscope foolish when it comes to the number of endoscopes available. Regarding esophageal dilators, the decision of whether to use a Savary or American dilator system versus balloons can have major economic consequences. This is less of an issue in the hospital where some device costs can be separately billed. However, in an office suite or an EASC, use of balloons and other expensive accessories such as hemoclips may be problematic, particularly with Medicare or Medicaid patients, for whom the facility fee is set by regulation and extra costs for accessories cannot be passed on. Finally, with the growing use of propofol or anesthesia services for endoscopic procedures, additional medications and equipment are often required for this service.30,31

Physical Environment

If the first two components operate properly, the number of procedure rooms available is not as important as the practice habits of the physician in performing procedures, talking to patients and their families, completing medical records, and returning to the procedure room.30 In an efficient facility, physician discipline is needed because room turnover and equipment reprocessing time can be rapid. Scheduled times for one physician operating out of two rooms with adequate staff and equipment can be easily allotted at 30 minutes for colonoscopies and 20 minutes for upper GI endoscopies (Rockford Gastroenterology Associates, Ltd., Rockford, IL, unpublished data).

Flow

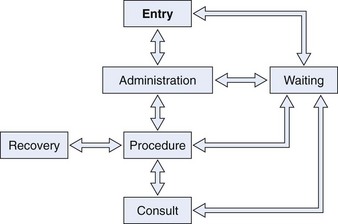

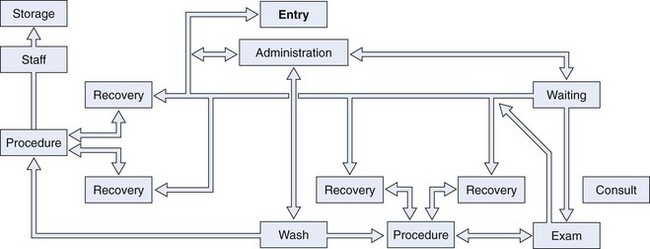

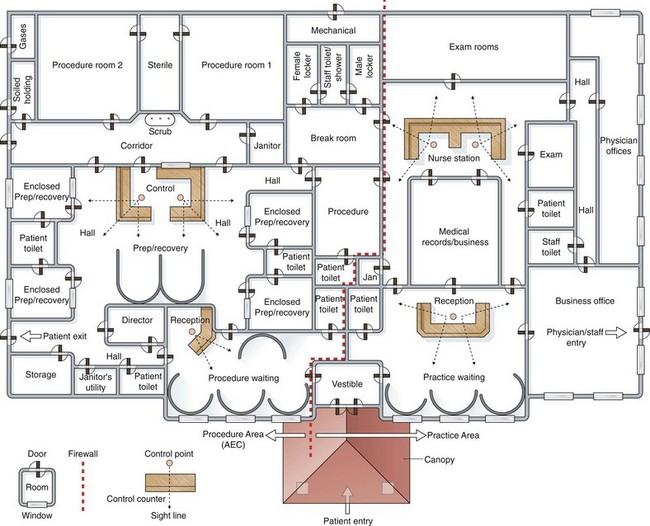

Architects use flow diagrams to plan movement patterns in arranging space before actual design plans. Physician and nurse input is crucial in arranging the flow relationships within the endoscopy facility to maximize efficiency, minimize travel distance, and achieve economy of movement. A basic flow diagram showing the components for a simple endoscopy unit is shown in Fig. 2.1. The patterns of movement in a more complicated facility are conceptualized in Fig. 2.2. Simple flow diagrams such as these can be elaborated into a functional relationship diagram as shown in Fig. 2.3. Although this diagram suggests a floor plan, it is not a true floor plan. The sizes of the areas within the diagram are not proportional to the actual relative sizes of the rooms they represent. This type of functional relationship diagram shows the way that patients, staff, physicians, and equipment move through the facility.

Fig. 2.1 Flow diagram for simple endoscopy unit.

(From Rich ME: Office layout and design. In Overholt BF, Chobanian SJ, editors: Office endoscopy, Baltimore, 1990, Williams & Wilkins.)

Fig. 2.2 Flow diagram for larger endoscopy unit.

(From Rich ME: Office layout and design. In Overholt BF, Chobanian SJ, editors: Office endoscopy, Baltimore, 1990, Williams & Wilkins.)

Fig. 2.3 Functional relationship diagram of ambulatory endoscopy center.

(From Marasco JA, Marasco RF: Designing the ambulatory endoscopy center. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 12:193, 2002.)

For hospital-based units, specific patient flow issues must be considered. Separate entrances for sick, bedridden patients and ambulatory individuals should be considered. The monitoring and treatment requirements for sick inpatients must be taken into consideration. Separation of inpatients and outpatients in waiting or holding areas, preparation areas, and recovery areas may also be helpful. In the example of an ambulatory endoscopy center shown in Fig. 2.3, an endoscopy facility and an adjacent clinic facility are shown. The endoscopy facility on one side of the firewall can qualify as an ASC if the rules and regulations are followed and the endoscopy facility is separated from the clinic building by a required 1-hour fire rated wall-door construction system. This construction is usually achieved by using a wall with two layers of fire-rated gypsum board on either side of the structural wall supports and having the wall extend through the ceiling to the roof of the structure above.32

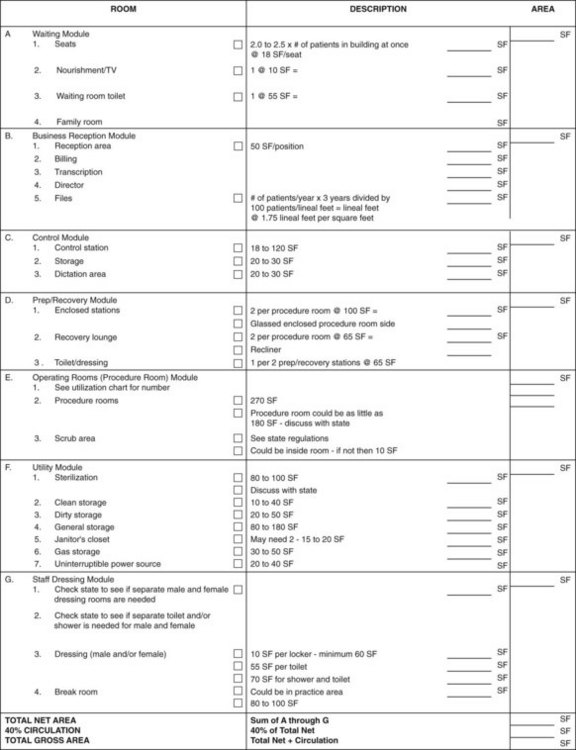

A functional relationship diagram can be turned into a floor plan by assigning actual space requirements to the rooms that are represented. Fig. 2.4 shows a sample architectural space program worksheet that can be used to turn a functional relationship diagram into a floor plan. A 40% circulation allowance must be added at the end of the tabulation to account for wall thicknesses, corridors, and so forth.32,33

Designing the Endoscopy Facility

The Guidelines for Design and Construction of Health Care Facilities (AIA Guideline), published by the American Institute of Architects (AIA) and the Academy of Architecture for Health, includes a section on the design and construction of GI endoscopy facilities. The document is updated on a 4- to 5-year revision cycle with the latest edition published in 2006 and a new version anticipated for 2010. The AIA Guideline, which is referenced by many federal and state jurisdictions, was originally conceived as minimum construction requirements for hospitals. Over time, the document has evolved to include engineering systems, infection control, and safety and architectural guidelines for design and construction of hospitals and other types of health care facilities. It provides an invaluable resource for the construction of a new ambulatory endoscopy center, the construction of a hospital-based endoscopy unit, or the renovation of existing units. The AIA Guideline can be purchased through the Facility Guidelines Institute (FGI) at http://www.fgiguidelines.org/about. For existing hospital facilities, many considerations are subject to limited space and resources and require a compromise between optimal choices and the realities of the existing building. Marasco and Marasco32,33 suggested designing the endoscopy facility in modules. The modules to be designed include the following:

Waiting Module

There has been a marked shift toward outpatient-based endoscopy since the mid-1980s. This shift has major implications for the design and operation of the endoscopy facility. The patient’s experience of the endoscopy facility often begins outside of the building in the parking lot. Patients arriving for endoscopy are often anxious and sometimes frightened. Maps with careful driving instructions and signs posted in the vicinity of the endoscopy facility can minimize confusion and offer reassurance. An all-weather canopy and automatic opening doors are helpful to elderly, ill, or disabled patients. The reception and waiting room area provides an early impression of the endoscopy facility and should project efficiency and friendliness. Wheelchair storage should be available in this area, with wheelchairs stored out of sight. There must be adequate room for patients’ escorts because one or two people usually accompany each patient scheduled for endoscopy. It is good to have a sub-waiting room for the endoscopy facility if there is an adjacent clinic area. A separate waiting area might be required under rules and regulations; even if not required, it might prove useful because waiting times for the clinic may be quite different from waiting times for patients undergoing endoscopy. The waiting areas should be well appointed and equipped with a television set, DVD player, and reading material. A toilet should be available near, but not directly off of, the waiting room. A small refreshment station near the reception area is also appreciated by escorts. The number of seats required is generally 2.5 times the number of patients in the building at any given time. The general waiting area for Rockford Endoscopy Center, Rockford Gastroenterology Associates, Ltd., Rockford, Illinois, is shown in Fig. 2.5.

Preparation-Recovery Module

The preparation-recovery area of the endoscopy facility requires constant patient surveillance from the nursing staff. This area usually contains a nursing control station (Fig. 2.6), which allows unobstructed viewing of patients during the preparation and recovery stages of their visit. The most efficient arrangement for preparation and recovery is to have them occur in the same place. Patient clothing can be stored in a locked cabinet in the preparation-recovery area or can accompany the patient during transport to the procedure room and back, stored underneath the rolling procedural stretcher cart. Patients can be rolled into procedure rooms on properly designed rolling carts that are also used as procedure tables. In this way, patients can move from preparation to procedure and back to recovery requiring no mounting or dismounting from wheelchairs or carts.

Procedure Room Module

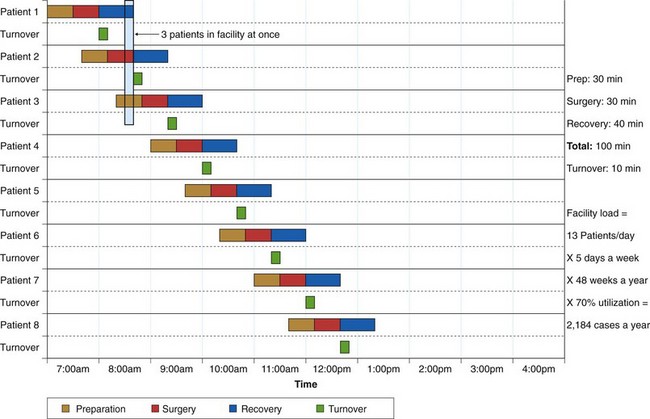

The number of procedure rooms is determined by the caseload of the endoscopy facility. This number is often overestimated. Much more important than the number of procedure rooms is the amount of recovery space available. In an efficient facility where turnaround time is quick, the number of procedure rooms can be minimized. It is most efficient for one endoscopist to have two rooms available so that turnaround between cases can be very rapid. Using procedure rooms for recovery compromises efficiency by tying up a specialized procedure room. Block scheduling of a single endoscopist with two rooms offers maximum efficiency. To determine the required number of procedure rooms, Marasco and Marasco32 recommended using a utilization chart, an example of which is shown in Fig. 2.7. By filling in the time of each of the time segments required in the endoscopy facility and adding the anticipated patient load, the number of procedure rooms needed can be estimated. Allowances should be made for growth in numbers of physicians and patients over the subsequent 5 years. Generally, annual caseloads increase 10% to 15% per year. By using the patient load anticipated 5 years hence and dividing this load by the number of procedures per room per year, the number of required rooms can be calculated. By examining vertically on the utilization chart, one can estimate the number of patients who will be in various stages within the endoscopy facility. This information can help predict the number of seats needed in the waiting room, the number of necessary procedure rooms, and the number of preparation-recovery bays and recliner chairs needed.

Fig. 2.7 Sample procedure room utilization analysis.

(From Marasco JA, Marasco RF: Designing the ambulatory endoscopy center. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 12:199, 2002.)

The minimum size for an endoscopy room is probably 200 square feet,1,24 but this is often inadequate to accommodate newer, larger videoendoscopy equipment, video monitors, and additional equipment for anesthesia services, if used. Approximately 300 square feet is more appropriate for the modern endoscopy room.1,32 Sometimes state licensing departments or Medicare mandates a minimum size for an “operating room” that is inappropriately large for an endoscopy room. In that instance, a variance can be requested, but it is not automatically granted.

In an endoscopy procedure room layout, placement of the light source, videoprocessor, dual video monitors, and electrocautery must be considered carefully. Many variations are possible to fit the preferences of the endoscopists and nursing staff. Rooms should be planned with equipment and supplies integrated into the layout and positioned strategically around the site of the patient on the procedural stretcher cart. The floor should be free of cables and wiring; these can be arranged along the perimeter of the room or preferably above a dropped ceiling or in the walls. This arrangement allows physicians, staff, and equipment to move unfettered by cords and cables and avoids damaging these sensitive components. All endoscopic accessories, suction, oxygen, supplies, and all resuscitation equipment should be at hand. An emergency call button should be included in each procedure room, and an emergency (crash) cart should be stored nearby. A typical endoscopy procedure room (Rockford Endoscopy Center) is shown in Fig. 2.8. A more detailed discussion of basic clearances and human dimensional requirements is provided by Waye and Rich.34

Utility Module

Efficient equipment turnover time can be achieved by having appropriate equipment for rapid cleaning and high-level disinfection. In this scenario, the speed of the endoscopy facility is determined by the efficiency of the physician between procedures rather than by the number of procedure rooms.32 Instrument cleaning and high-level disinfection can be accomplished by strategically placing the cleaning area between two procedure rooms or having an efficient large cleaning area within a short distance of several procedure rooms. Adequate numbers of endoscopes stored properly and reprocessed efficiently ensure that the most expensive cost elements of the endoscopy facility—the physicians and nursing staff—are not kept waiting for equipment.

Cleaning rooms should be large and adequately ventilated with ample plumbing and power provisions for future changes. Oversized sinks are required, and there should be a place for soiled instruments to hang while waiting to be cleaned. Automated endoscope washers with multiple scope compartments, such as that shown in Fig. 2.9, provide an efficient way of reprocessing endoscopes. Different instrument reprocessing units vary in their cleaning time, which has an impact on the number of scopes required by a busy unit. A “pass through” window from soiled to clean utility areas should be available to maintain separation of “clean” and “dirty” areas.

A closed cabinet for the storage of clean endoscopes is preferred to open storage to protect instruments and to prevent inadvertent sightings of instruments by anxious patients. Endoscope storage cabinets that circulate air through the endoscope channels provide added protection against moisture and bacterial growth within channels. A storage unit with channel air circulation is shown in Fig. 2.10. Exhaust fans in the cleaning area are a must, as are provisions for disposal of toxic chemicals. Also included in the utility module are storage areas. General storage for supplies must be readily accessible to the preparation-recovery areas and the procedure rooms. There must be locked cabinets for storage of drugs. Biohazardous waste and gases such as oxygen must also be stored. An alternative power source, such as a battery backup system or generator, is necessary to ensure uninterrupted power.

Staffing and Scheduling

Staffing

Decisions regarding staffing hinge on regulatory requirements, volumes of procedures, and case mix (disease acuity). Numerous federal and state regulations affect staffing decisions, and a thorough knowledge of these requirements is necessary to ensure compliance with state licensing requirements, Medicare certification regulations, and third-party accreditation standards.35,36

Medicare guidelines stipulate that a registered nurse (RN) must be available on site during all hours of operation of a hospital or ASC endoscopy facility. The nurse practice act of each individual state also affects staffing decisions. A state nurse practice act defines the scope of practice for RNs, licensed practical nurses (LPNs), and other assistants or technicians. These nurse practice acts may limit who can start intravenous (IV) lines, administer IV medications, or provide other clinical services. To determine the number of full-time equivalents (FTEs) needed for staffing, one must quantify the time needed to care for a single patient, multiply this by the number of procedures scheduled daily, and divide by the work hours per day of a full-time employee. One current industry standard suggests an average time of 3 hours per procedure to admit, treat, and discharge a patient in an endoscopy facility (AMSURG Corporation, unpublished data).35 Some factors that influence the decision to use RNs versus LPNs versus technicians include scope-of-practice regulations, salary costs, and availability. Regardless of the mix, care should always be directly supervised by an on-site RN.37

A typical two-room endoscopy facility might be staffed as follows:35

Scheduling

Most facilities use block scheduling to maximize efficiency and convenience.35,36 Block scheduling of one physician with two endoscopy rooms allows efficient movement of the endoscopist from one room to the next without delays caused by other endoscopists. It is possible for that individual to intermingle daily tasks such as telephone calls or chart review during any downtime. Block scheduling also allows for time allotments based on the performance characteristics of individual endoscopists. Examples of block scheduling and tools for use in block scheduling have been published by McMillan.35 Equipment availability can affect scheduling. An ample number of endoscopes and rapid, efficient cleaning and high-level disinfection facilitate a more efficient schedule.

The first patient of the day can be prepared in the procedure room if an additional procedural stretcher cart is available for each procedure room at the beginning of the day. Time allotments for procedures vary from facility to facility. Reportedly, most facilities allow 45 minutes for colonoscopy and 30 minutes for upper GI endoscopy.35 Other facilities schedule more tightly, allowing 30 minutes for colonoscopy and 20 minutes for upper GI endoscopy, including procedures with dilations (Rockford Gastroenterology Associates, Ltd., Rockford, IL, unpublished data). The tighter scheduling can be accommodated by efficient endoscopists, good staffing, adequate equipment, rapid turnaround time, and ample preparation-recovery space (two to three preparation-recovery bays per procedure room). Careful staffing and scheduling are imperative to ensure high-quality care, good patient outcomes, and optimal fiscal performance of the endoscopy facility.

Documentation and Information Technology

An accurate and complete medical record for each patient and a log of the unit’s overall activities must be kept (see Chapter 9).1 The endoscopy report and nursing notes should include date, patient identification data, endoscopist, specific instruments used, endoscopic procedure, indications, informed consent, extent of examination, duration of procedure, findings, notation of tissue sampling, therapeutic interventions, complications, and limitations of the examination. Photographs, electronic images, and biopsy reports should also be part of the record. Quality indicators and patient outcomes should be tabulated, and a method of regular peer review should be developed.7 Information management in an endoscopy facility affects all aspects of the operation, including scheduling, billing and reimbursement, patient medical record, procedure reports, clinical laboratory and anatomic pathology reports, imaging, pharmacy, patient education, performance improvement data, financial management, materials management and inventory, budgeting and forecasting, payroll and personnel, and staffing and scheduling.38 Modern information technology may allow more efficient and effective operations within the facility. Information technology is changing medical practice at a rapid pace and may allow more efficient and effective operations within the endoscopy facility.

Quality Measurement and Improvement

Increasing health care costs, constrained resources, and evidence of variations in the quality of care rendered have triggered a renewed emphasis on quality measurement and improvement. Two reports by the Institute of Medicine advocate widespread changes in health care, including paying for performance as a means of achieving the delivery of high-quality care.39,40 Medicare regulations and third-party accreditors require endoscopy facilities to engage in an ongoing comprehensive self-assessment of the quality of care provided. This process includes quality improvement efforts directed toward numerous facets of the operation of the facility. Reasons for quality improvement activities include ensuring that patients receive the highest quality of care possible; providing a competitive edge when seeking contracts; and addressing the recent emphasis of legislators and regulators on quality improvement activities as part of the licensure, certification, and accreditation process. Johanson41,42 described continuous quality improvement in the ambulatory endoscopy center. The philosophies and tools presented in this article provide a framework for quality improvement activities in all endoscopic facilities. A 2006 publication by a joint task force from the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and the ASGE provides an excellent resource with recommendations and ranking of quality indicators that can be used as a starting point in quality measurement and improvement efforts.7

1 American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Establishment of gastrointestinal endoscopy areas. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:910-912.

2 American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Principles of training in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:845-853.

3 American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Methods of granting hospital privileges to perform gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:780-783.

4 Petrini JL. Credentialing and privileging. In: Frakes JT, editor. Ambulatory endoscopy centers: a primer. Oak Brook, IL: American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy; 2006:49-51.

5 American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Quality improvement of gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:842-844.

6 American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Quality and outcomes assessment in gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:827-830.

7 American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy. Measuring the quality of endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;58:S1-S38.

8 Pike IM. Outpatient endoscopy: Possibilities for the office. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:247-261.

9 Pike IM. The office-based endoscopy unit: An alternative to an ambulatory surgery center. Ambulatory endoscopy centers: a primer. 2006:17-22.

10 Frakes JT. The ambulatory endoscopy center (AEC): What it can do for your gastroenterology practice, 16. Gastrointest Endoscopy Clin N Am. 2006.

11 Frakes JT. The importance of the ambulatory endoscopy center to the gastroenterology practice. Ambulatory endoscopy centers: a primer. 2006:3-6.

12 Center for medicare and medicaid services. ASC payment. Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/ASCpayment/ Accessed September 18, 2009

13 Vicari JJ, Garry N. Exploring possibilities: Types of facilities and business plan. In: Frakes JT, editor. Ambulatory endoscopy centers: a primer. Oak Brook, IL: American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; 2006:23-27.

14 Deas TM. Assessing the financial health of the endoscopy facility. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:229-244.

15 Deas TMJr. Assessing financial performance. In: Frakes JT, editor. Ambulatory endoscopy centers: a primer. Oak Brook, IL: American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy; 2006:73-77.

16 Overholt BF. Office endoscopy or an endoscopic ambulatory surgery center? Gastroenterologist. 1993;1:99-106.

17 Ganz RA. Regulation and certification issues. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:205-214.

18 Feninger RB. Regulatory issues. In: Frakes JT, editor. Ambulatory endoscopy centers: a primer. Oak Brook, IL: American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy; 2006:33-36.

19 Knox C, Mellow MH. Functional plan and architectural issues. In: Baerg RD, Frakes JT, Mellow MH, et al, editors. The development of an ambulatory endoscopy center: a primer. Manchester, MA: American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy; 1998:6-11.

20 Romansky M. Medicare certification of ambulatory surgical centers. In: Baerg RD, Frakes JT, Mellow MH, et al, editors. The development of an ambulatory endoscopy center: a primer. Manchester, MA: American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy; 1998:12-13.

21 Joint commission on accreditation of healthcare organizations. Ambulatory care accreditation. Available at http://www.jcaho.org Accessed April 19, 2003

22 Accreditation association of ambulatory health care. Products, resources. Available at http://www.aaahc.org Accessed April 19, 2003

23 Safdi MA. Accreditation and Medicare certification. In: Frakes JT, editor. Ambulatory endoscopy centers: a primer. Oak Brook, IL: American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy; 2006:69-71.

24 Rich ME. Office layout and design. In: Overholt BF, Chobanian SJ, editors. Office endoscopy. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1990:31-50.

25 Waye JD, Rich ME. Constructing the unit: Plans and problems. In: Planning an endoscopy suite for office and hospital. New York: Igaku-Shoin; 1990:129-145.

26 Schapiro M. Office design and planning: The physician’s viewpoint. In: Overholt BF, Chobanian SJ, editors. Office endoscopy. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1990:9-29.

27 Herzlinger R. Market driven health care: who wins, who loses in the transformation of america’s largest service industry. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1997.

28 Deas TMJr, Drerup DM. Endoscopic ambulatory surgery centers: Demise, service or thrive? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:253-256.

29 Waye JD, Rich ME. Program. In: Planning an endoscopy suite for office and hospital. New York: Igaku-Shoin; 1990:33-45.

30 Weinstein ML, Vargo JJ. Anesthesia services in the ambulatory endoscopy center. Ambulatory endoscopy centers: a primer. 2006:135-141.

31 Aisenberg J, Cohen LB. Sedation in endoscopic practice. Gastrointest Endoscopy Clin N Am. 2006;16:695-708.

32 Marasco JA, Marasco RF. Designing the ambulatory endoscopy center. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:185-204.

33 Marasco JA. Ambulatory endoscopy centers: facility planning and design. In: Frakes JT, editor. Ambulatory endoscopy centers: a primer. Oak Brook, IL: American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy; 2006:37-43.

34 Waye JD, Rich ME. The procedure zone. In: Planning an endoscopy suite for office and hospital. New York: Igaku-Shoin; 1990:73-101.

35 McMillin DF. Staffing and scheduling in the endoscopy center. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:285-296.

36 Winker CK. Staffing and scheduling in the endoscopic ambulatory surgical center. Ambulatory endoscopy: a primer. 2006:45-48.

37 Society of gastroenterology nurses and associates (SGNA). Role delineation of assistive personnel. Position statement. 2001. Chicago: SGNA. 2001.

38 Weinstein ML, Korman LY. Information management. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:313-324.

39 Institute of Medicine. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999.

40 Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

41 Johanson JF. Continuous quality improvement in the ambulatory endoscopy center. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:351-365.

42 Johanson JF. Quality assurance and quality improvement. In: Frakes JT, editor. Ambulatory endoscopy centers: a primer. Oak Brook, IL: American society for gastrointestinal endoscopy; 2006:95-103.