CHAPTER 15 Setting Up a Sclerotherapy Practice

Providers

Before proceeding with the practical aspects of establishing a practice, one must decide who will deliver patient care. Most physicians agree that a physician should perform the sclerotherapy procedure; however, some clinics use nurses to treat spider telangiectasias. A survey of the membership of the North American Society of Phlebology (NASP) (now the American College of Phlebology (ACP)) found that approximately 25% of the members would allow a registered nurse and 20% would allow a nurse practitioner to perform sclerotherapy on spider veins.1 Of NASP members surveyed, 10% would allow a registered nurse to perform sclerotherapy on varicose veins versus 7% who would allow nurse practitioners to perform this procedure. Registered nurses can legally perform intravenous therapeutic injections in most states. Physicians should check with the state licensing board for nursing for the specific requirements.

Because the cannulation of a blood vessel is relatively easy to perform and few serious or life-threatening complications can arise from sclerotherapy treatment of spider telangiectasias, an argument can be made for using nonphysicians as sclerotherapists. On the other hand, although rare, serious complications can result from injection of spider telangiectasias. Anaphylactic allergic reactions have occurred with many sclerosing agents; a fatality was reported after a ‘trial’ injection of sodium tetradecyl sulfate.2 Pulmonary emboli also have occurred from the injection of leg telangiectasias (see Chapter 8). Injection into an arteriovenous anastomosis usually produces a cutaneous ulceration, and cutaneous ulceration from sclerotherapy injection (extravasation or arteriolar injection) is the most common reason (in sclerotherapy) for medical malpractice litigation. Injection into a superficial artery, especially around the malleoli, can lead to arterial emboli and pedal gangrene. Duplex-guided injections into deep perforating veins can cause significant muscular necrosis requiring leg amputation. Thus, as with most of medicine, sclerotherapy is not entirely risk-free. The physician is ultimately responsible for ensuring that the nurse is properly trained both in performing sclerotherapy and in recognizing adverse sequelae. The physician, not the nurse, will be the one sued for malpractice.

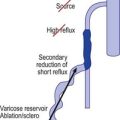

In addition to being skilled at sclerotherapy technique, the sclerotherapist must have a thorough knowledge of the anatomy and pathophysiology of venous disease and of the mechanism of action of the procedure, including its potential complications. The ability to appreciate these mechanisms and immediately recognize potential complications and render preventive treatment is critical to maintaining optimal patient care. Furthermore, a thorough understanding of vascular hemodynamics, including the relationship between deep and superficial venous insufficiency, is imperative to those practicing sclerotherapy. For example, venous segments with a certain degree of incompetence are best initially treated with endovenous ablation, which removes the source of venous hypertension, thus reducing or eliminating progression of reflux to other surrounding veins.3,4 Not being trained to recognize when endovenous ablation is a necessary portion of the overall treatment approach results in inadequate improvement following sclerotherapy. Thus, clinical judgment as well as technical skill are both essential attributes in an effective sclerotherapist.

Hallgren et al5 defined basic nursing assessment skills and the requirements for transfer of function of the nurse in a sclerotherapy–phlebology practice. In short, for a nurse to function as a sclerotherapist, the following must be known:

This knowledge base should also include instruction so that the nurse can do the following:

In conclusion, nurses who practice phlebology must be actively involved in the practice of nursing when delivering care. They should be able to prepare not only the operating room for the procedure, but also the patient for the procedure by answering questions, allaying fears, and documenting pretreatment disease. In addition, follow-up treatments allow the nurse the opportunity to reinforce patient teaching so that preventive measures can be emphasized. For an excellent demonstration of lower extremity superficial venous examination techniques, the reader is encouraged to refer to an educational DVD provided by the American College of Phlebology partnered with the Society of Vascular Ultrasound.6 Various other comprehensive textbooks on sclerotherapy, phlebectomy, and venous ultrasound techniques are available; we have referenced those textbooks that we feel are the most useful at the end of this chapter.7–10

Facility

Endovenous laser ablation of leg veins is best performed in a non-facility setting, as this eliminates additional facility fees associated with procedures performed in a hospital or ambulatory care facility. By having his/her procedure performed in an outpatient setting, patients save money by not having to pay facility fees, and practitioners generate more revenue by not having to split reimbursement payments with a facility.11

Equipment

Relatively little specialized equipment is required to perform successful sclerotherapy. Various types of lasers may also be required for treating specific types of leg veins (see Chapter 13). For now, all that is required is a needle, syringe, sclerosing solution, binocular loupe, foam pads, tape, graduated support stockings, and camera. (![]() See online Appendix C for information on manufacturers.) Although serious adverse events are rarely encountered during the treatment of leg veins, appropriate resuscitation equipment must be readily accessible throughout the procedure. Patients occasionally experience vasovagal reactions during the treatment of leg veins; ammonium capsules as well as oxygen can help mitigate these reactions. Other equipment, including an emergency resuscitation (crash) cart as well as an electrocardiograph, should remain readily accessible throughout the procedures.12

See online Appendix C for information on manufacturers.) Although serious adverse events are rarely encountered during the treatment of leg veins, appropriate resuscitation equipment must be readily accessible throughout the procedure. Patients occasionally experience vasovagal reactions during the treatment of leg veins; ammonium capsules as well as oxygen can help mitigate these reactions. Other equipment, including an emergency resuscitation (crash) cart as well as an electrocardiograph, should remain readily accessible throughout the procedures.12

Ultrasound devices

A duplex ultrasound device is essential for both diagnosis and treatment of venous disease. It can help discern superficial and deep venous insufficiency, allow for pretreatment vein mapping, provide imaging and guidance during the procedure, and allow for postoperative assessment of therapeutic efficacy.13

Needles

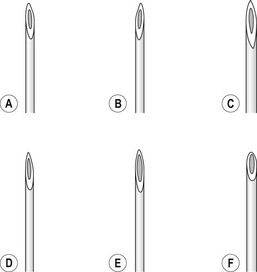

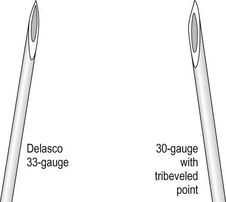

The injection of telangiectasias requires a fine-gauge needle. A needle with a clear plastic hub instead of a metal hub is useful to allow visualization with aspiration. Although some physicians prefer to use a 32- to 33-gauge or 26- to 27-gauge needle, we prefer the 30-gauge needle. There are two types of 30-gauge needles. One is the Becton-Dickinson (B-D) Precision Glide needle (Becton, Dickinson & Co, Rutherford, N.J.), which has an elongated bevel on a ½-inch needle with a 45-degree angle at the tip. The needle can be easily bent at varying angles to penetrate telangiectasias. In addition, it is relatively sharp and holds up well when used for multiple punctures of the skin. The second type is a tribevel tipped needle. The Acuderm (Acuderm, Ft Lauderdale, Fla.) and Delasco (Dermatologic Lab & Supply, Council Bluffs, Iowa) 30-gauge needles have a  -inch metal hub and a silicone-coated tribevel point. This type is preferred because its silicone coating and more acute angle at the tip allow it to pierce the skin with less pain. In addition, the length of the bevel is shorter than that of the B-D needle. Accordingly, extravasation of solution perivascularly while the needle is in the vessel lumen is less likely. Tribeveling of the tip also makes it harder, so it retains its sharpness with multiple injections. A comparison of the bevels of all of the recommended needles is shown in Figure 15.1. However, even with this magnified comparison, the differences between the needle tips cannot be fully appreciated. Clinical trials using each needle type are necessary to discern the subtle differences.

-inch metal hub and a silicone-coated tribevel point. This type is preferred because its silicone coating and more acute angle at the tip allow it to pierce the skin with less pain. In addition, the length of the bevel is shorter than that of the B-D needle. Accordingly, extravasation of solution perivascularly while the needle is in the vessel lumen is less likely. Tribeveling of the tip also makes it harder, so it retains its sharpness with multiple injections. A comparison of the bevels of all of the recommended needles is shown in Figure 15.1. However, even with this magnified comparison, the differences between the needle tips cannot be fully appreciated. Clinical trials using each needle type are necessary to discern the subtle differences.

Some sclerotherapists advise the use of a 33-gauge needle to cannulate the smallest diameter telangiectasia. Multiple 31- to 33-gauge  -inch needles are available (Fig. 15.2). These needles have several drawbacks. They are more expensive than 30-gauge needles and must be cleaned and sterilized between patients if they are not disposed of (this is of concern to patients who fear inadequate sterilization with the subsequent risk of blood-borne pathogens). Repetitive sterilization also dulls the needle point. In addition, the tips of these needles bend and dull more quickly than those of the 30-gauge needles, and the needle shafts are thinner and thus less stable during injections through tough skin. John Phiffer (personal communication, 1992) reported on the construction of a rigid shaft used to support the 32-gauge needle tip to help stabilize it. However, as mentioned previously (Chapter 12), we find these needles of little use.

-inch needles are available (Fig. 15.2). These needles have several drawbacks. They are more expensive than 30-gauge needles and must be cleaned and sterilized between patients if they are not disposed of (this is of concern to patients who fear inadequate sterilization with the subsequent risk of blood-borne pathogens). Repetitive sterilization also dulls the needle point. In addition, the tips of these needles bend and dull more quickly than those of the 30-gauge needles, and the needle shafts are thinner and thus less stable during injections through tough skin. John Phiffer (personal communication, 1992) reported on the construction of a rigid shaft used to support the 32-gauge needle tip to help stabilize it. However, as mentioned previously (Chapter 12), we find these needles of little use.

Syringes

The 3-mL plastic syringe, Luer-Lok (Becton, Dickinson), is used exclusively in our practice. This syringe allows the use of an ideal quantity of solution, and when filled to a 2-mL capacity, it fits easily in the palm of the hand. However, a non-Luer-Lok syringe has the advantage of possessing a needle hub that is able to separate from the syringe if resistance, which indicates noncannulation of a vessel, is encountered. Each syringe manufacturer coats the inner portion of the syringe with silicone to allow smooth action by the plunger. The addition of silicone to coat the barrel of the syringe has also been shown to decrease the half-life of bubbles when foam is generated in the syringe (see Chapter 9). If using foam, one may wish to use a syringe with the least amount of silicone coating. The physician should evaluate different types of syringes to determine which has the best feel for his or her use.

If one does not bend the needle to facilitate penetration of the vein, the Plastipak eccentric syringe (Fig. 15.3) is useful. With this syringe, the hub is eccentrically placed at the syringe tip so that it abuts the skin surface. It is available in sizes of 1, 2, 5, and 10 mL.

Sclerosing solutions

The various sclerosing solutions available are discussed in detail in Chapter 7. Addresses of the manufacturers and distributors of these solutions are listed online in Appendix B![]() .

.

Binocular loupes

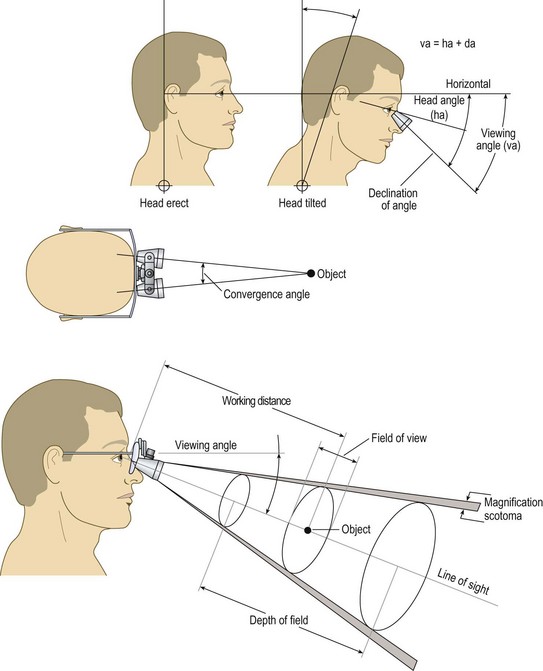

The ideal magnifier provides a wide field of view with distortion-free magnification within a reasonably long working distance and ergonomic viewing angle (Fig. 15.4). Unfortunately, with currently available optics, the higher the magnification, the smaller the field of view and depth of field. Complex, multilens binocular magnifiers overcome some of the limitations of short working distances. Some of these magnifiers are detailed online in Appendix C![]() . An independent evaluation of magnifiers appears in another source.14,15

. An independent evaluation of magnifiers appears in another source.14,15

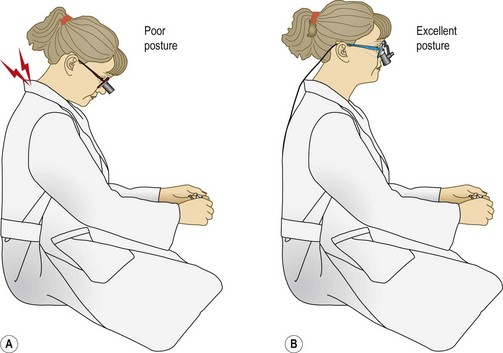

The ideal ergonomic magnifier would be comfortable to wear (lightweight with comfortable nose pads), allow a comfortable working distance, and maintain the surgeon’s neck and back in a neutral position (Fig. 15.5). An increase in the head/neck tilt angle causes neck muscle fatigue.16 Working with proper posture thus decreases stress and fatigue.

When choosing the proper magnification, five factors must be addressed:

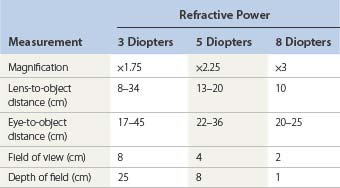

Table 15.1 shows a comparison of these factors in regard to a person with normal focusing-converging ability. Note that magnifications greater than 5 diopters decrease the field of view and depth of focusing sufficiently to make their use impractical for sclerotherapy. In our experience, lenses with 2× to 3× power provide the ideal combination of focal distance and magnification.

Magnifying glasses

Half-frame clip-on lenses are available in multiple powers. The most useful is a 5-diopter, 2.25×-power lens with a 19-cm focal distance. These lenses produce marked peripheral distortion but have a usable field of view of 7 cm for the 3-diopter and 5 cm for the 5-diopter lens. The working distance from lens to object is 17 cm for the 3-diopter and 12 cm for the 5-diopter lens (Fig. 15.6). This type of magnification aid is available from most opticians and department stores.

Headband-mounted simple binocular magnifiers

Headband-mounted magnifiers are available equipped with interchangeable lens plates that provide a range of magnification from 1.5× to 3.5× (Fig. 15.7). These magnifiers can be worn comfortably over prescription eyeglasses. The most widely used magnifications with the least peripheral distortion and best working distance are 2.3× and 2.5×. An optional Optiloupe (Donegan Optical Co, Lenexa, Kan.) attachment lens adds 2.5× magnification to any base lens but has a very small field of view without distortion. These magnifiers are available from many manufacturers and vary in price, type of headgear padding, and adjustability; Optivisor (Donegan Optical) and Mark II Magni-Focuser (Edroy Products Co, Nyack, N.Y.) are two examples.

Simple binocular loupes

The Precision (Almore International, Beaverton, Ore.) binocular loupe comes with varying diopter loupes fitted on a double-hinged telescoping rod so that the eye-to-object distance can be adjusted. It is available with 3-, 5-, or 8-diopter lenses17 (Fig. 15.8) and is also available as a multidistance headband-mounted loupe. Available powers include 1.5×, 1.75×, 2.25×, and 2.75×, with working distances from 50 to 15 cm, respectively.

Multilens binocular magnifiers

Epstein14 found the Designs for Vision (Ronkonkoma, N.Y.) loupe best suited for dermatologic examination. The working distance of this loupe is 35 cm for the 3.5× and 40 cm for the 2.5× magnifier. These magnifiers have the ocular structure secured to the lenses of the glass. The viewing angle is thus locked into position and can be customized only to the original operator’s posture. A disadvantage of this loupe system is a restriction of the peripheral vision to as little as 10%. This necessitates removing the loupes to view anything outside the working area.

Heine (Cary, N.C.) binocular loupes come in 2×, 2.5×, 3.5×, 4×, and 6× power (Fig. 15.9). The most useful power for sclerotherapy is the 2.5× model, which has a working distance of 34 cm with a field of view of 75 mm. The Gallilean optics are shorter than most other loupes and are lightweight (80 g). They are available on a large or small spectacle frame. Like many other loupes, the Heine loupe has both an asymmetric pupil distance adjustment and two alternate height settings for the optics.

Figure 15.9 2.5× magnification Heine HR® loupe on a S-frame.

(Courtesy of Delasco Dermatologic Lab and Supply, Inc., Council Bluffs, Iowa.)

The Keeler (Broomall, Pa.) panoramic surgical loupe has the following advantages: optics that can flip up out of view when not needed, lightweight frames, and optics with an antireflection coating. The 2.5× magnification loupe (Fig. 15.10) has a field size of 9.4 cm and a working distance of 42 cm. A 3× magnifier is available with a working distance of 34 cm and a field size of 6.2 cm or with a working distance of 50 cm and a field size of 7.6 cm.

Orascoptic Research, (Madison, Wis.) has a wide-field loupe of outstanding quality available in 2×, 2.35×, 2.6×, and 3.25× power (Fig. 15.11). There is no distortion across the entire field of view. The field of view is approximately 124 mm for the 2×, 88 mm for the 2.35×, 100 mm for the 2.6×, and 50 mm for the 3.25× loupes. These loupes are ergonomically designed with a downward sightline that can be adjusted to the exact angle that is most useful and comfortable for the physician, allowing a more upright posture, which reduces back and neck strain. The working distance for the 2.0× model is 12 to 17 inches (30 to 43 cm). A long-range option is available for persons over 6 ft tall (183 cm) and works in the seated position. The 2.0× model provides a working distance here of 15 to 21 inches (38 to 53 cm). For those who require a longer working distance, an extra-long range is available as well. The 2.0× model has a range of 17 to 23 inches (43 to 58 cm).

Figure 15.11 Orascoptic telescope shown with optional side shields and flip-grip autoclavable handle.

(Courtesy of Orascoptic Research, Inc., Madison, Wis.)

The SurgiTel loupe from General Scientific Corporation (Ann Arbor, Mich.) is similar to the Orascoptic loupe. It is available in 2.15×, 2.75×, 3.5×, and 5× power. It also has five adjustments to optimize the viewing angle. The lightweight frames come in two sizes with available side shields. The 2.75× loupe (most useful for sclerotherapy) has a field of view of 58 to 106 mm with a working distance of 250 to 404 mm or a 66- to 136-mm field of view with a 312- to 553-mm working distance, depending on the model type. These loupes also come with a fiberoptic light source that is small and well-balanced (Fig. 15.12).

Fig 15.12 SurgiTel loupes with micro-mini fiberoptic light.

(Courtesy of General Scientific Corporation, Ann Arbor, Mich.)

Other, less expensive models include the N1064 Oculus loupe (Orascoptic) (Fig. 15.13). Another, the Westco 2× to 2.5× adjustable loupe, is also less expensive and of excellent quality. The lens-to-object working distance is 13 cm with a 3-cm field of view at 2.5×.

Polarizing magnification

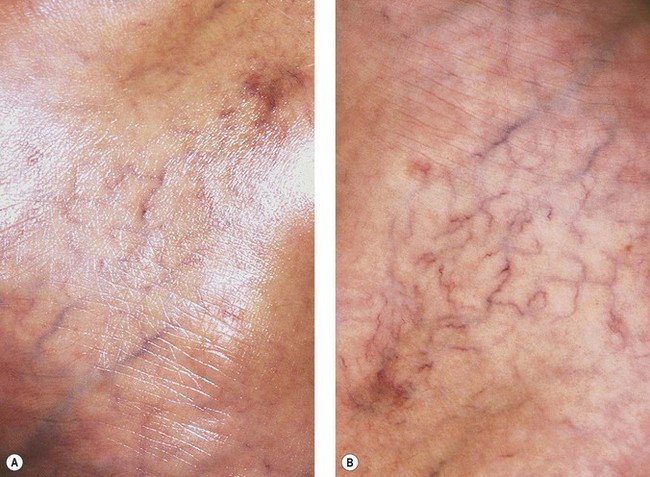

Syris Scientific (Gray, Me., USA) makes a vision enhancement system consisting of headband-mounted simple binocular magnifiers that expand the use of this low-cost magnification device with the incorporation of a dual polarizing system (Fig. 15.14). The use of polarization eliminates reflected light to enhance the appearance of vascular structures on the skin (Fig. 15.15). The tungsten-halogen light source is cooled with a microfan and has an operating lifetime of more than 400 hours.

Figure 15.15 A, Appearance of leg veins without polarization. B, Appearance of leg veins with polarization.

(Courtesy of Syris Scientific LLC, Gray, Me.)

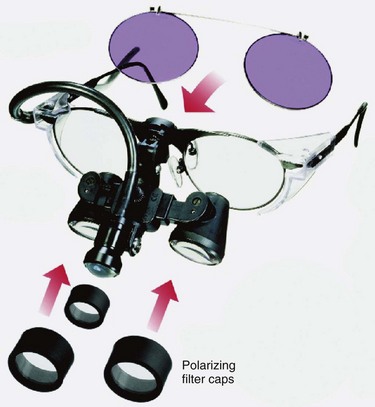

SurgiTel loupes also offer polarization with the attachment of a micro-mini fiberoptic light fitted with a polarizing cover. The loupes are then fitted with polarizing filter caps (Fig. 15.16).

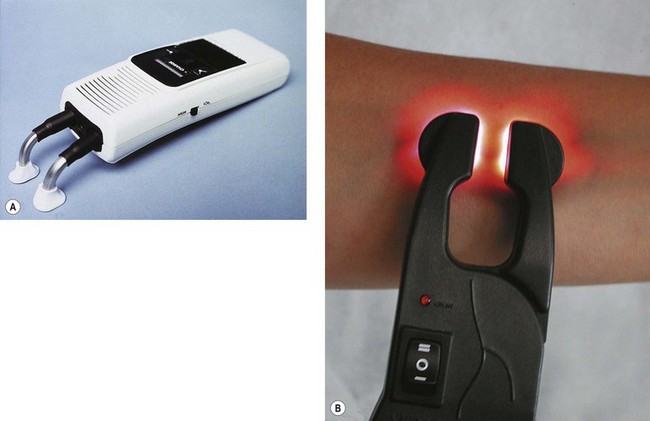

Transillumination

The Venoscope transilluminator (Applied Biotech Products, Lafayette, La.) assists in locating and visualizing vessels 1 to 2 mm below the skin. Dual fiberoptic light guides shine light from krypton lamps though adjustable fiberoptic arms. This device is most useful to mark veins in the surgical supine position before ambulatory phlebectomy and may also be useful in visualizing feeding reticular veins (Fig. 15.17A). A newer model is lighter and comes available with disposable plastic covers (Fig. 15.17B).

Figure 15.17 A, Venoscope transilluminator used to visualize superficial reticular and telangiectatic veins. B, LED model.

The Veinlite (TransLite LLC) is a second transillumination device for imaging reticular and telangiectatic leg veins. It has a large ring 150-W illuminator lighting system powered through a 6-foot-long fiberoptic cable. The ring has an outer diameter of 62 mm and an inner open diameter of 36 mm. The light output can be adjusted by a rheostat (Fig. 15.18A). A smaller model, the Veinlite LED, has a C-shaped design with side-illumination in 12, two-color light emitting diodes (LEDs) of orange and red to allow visualization of veins through any skin color (Fig. 15.18B). It also comes with disposable plastic covers. A newer model, the Veinlite II, has an additional high-contrast filter to more clearly highlight superficial veins. Alternately, its white light setting allows for detection of deeper varicose veins. The Veinlite II also comes with disposable covers, as well as an autoclavable ring.

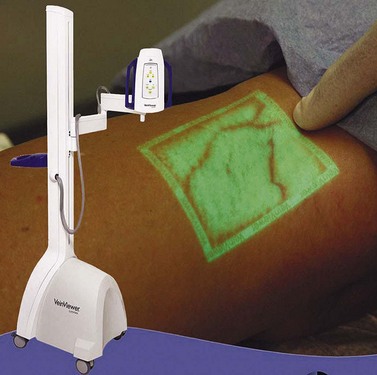

The VeinViewer (Fig. 15.19), patented by Luminetx Corporation of Memphis, Tenn, provides an innovative approach to visualization of subcutaneous veins. The device, which was introduced in 2005 and began to be distributed in 2006, makes subcutaneous, reticular veins visible by projecting real-time images of the exact location of veins directly onto the skin. The VeinViewer uses a near infrared light source to image the hemoglobin in red blood cells, allowing a video camera to capture the images. The video images are processed through a computer and the venous images are projected onto the patient’s skin within 0.06 mm of their exact location. The sclerotherapist can quickly and accurately map the veins which feed cutaneous blemishes and then proceed to definitive and accurate therapy using foam or liquid.

Endovenous ablation systems

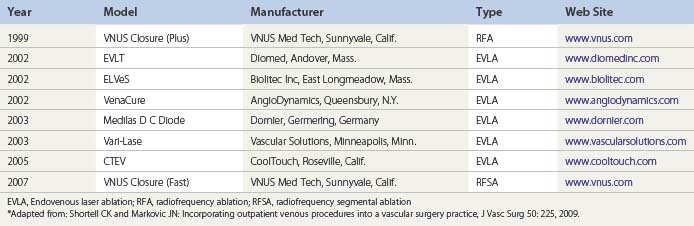

Initially, the practitioner wishing to begin incorporating leg vein procedures into his/her treatment armamentarium should invest in a single modality for endovenous thermal ablation (radiofrequency or laser). As the practice grows, the sclerotherapist should consider providing patients with the full spectrum of treatment modalities for superficial vein reflux disease (i.e. radiofrequency, endovenous laser ablation, and ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy).18 Table 15.2 lists endovenous thermal ablation systems currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration.12

Phlebectomy instruments

While the ambulatory phlebectomy technique is discussed elsewhere in this text (Chapter 10), this section will focus on the surgical instruments necessary to perform the procedure. At the very least, a practitioner performing ambulatory phlebectomy should have the following instruments on his/her surgical tray: a vein hook (Mueller, Goldman-Kabnick, Oesch, Ramelet, or Varady types), at least two sets of curved venous forceps, iris scissors, and an 11-blade. A blunt probe is also necessary to free the veins from the surrounding fascial attachments. Wagner Medical offers a wide array of vein hooks and venous forceps, including a newer venous forcep designed with elongated teeth, which promotes a more secure grip on veins.

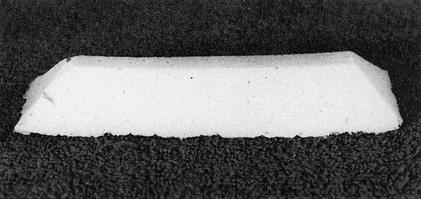

Foam pads

Foam compression pads (Fig. 15.20) are manufactured from white latex rubber. They are beveled to produce maximum compression along the line of the injected vein segment. STD Pharmaceutical distributes two sizes of pads useful for providing additional compression over varicose veins (see Chapter 6): D pad (5 cm ×13 cm × 2.5 cm high) and E pad (4 cm ×13 cm × 1.75 cm high).

Graduated compression stockings

Information about graduated compression stockings can be found in Chapter 6 and online in Appendix A![]() . One useful aid to help support the thigh stocking in the proper position on the leg is a body adhesive called ‘It Stays!’ (Beiersdorf-Jobst, Charlotte, N.C.). This body adhesive comes in a roll-on bottle; it does not dry on the skin, and it remains tacky until it comes in contact with water. The product is nontoxic and nonflammable and only rarely causes skin irritation.

. One useful aid to help support the thigh stocking in the proper position on the leg is a body adhesive called ‘It Stays!’ (Beiersdorf-Jobst, Charlotte, N.C.). This body adhesive comes in a roll-on bottle; it does not dry on the skin, and it remains tacky until it comes in contact with water. The product is nontoxic and nonflammable and only rarely causes skin irritation.

Another useful device to support vulvar varicosities is the V2 Supporter (Prenatal Cradle Inc., Hamburg, Mich.) (Fig. 15.21) (see Chapter 6).

Photography

Photographic documentation is recommended when treating any patient with varicose or telangiectatic leg veins. Not only do many insurance companies require photographic documentation before approving reimbursement, but also patients often cannot remember later exactly how their leg veins appeared initially. In addition, because varicose telangiectatic leg veins may continue to appear throughout a patient’s lifetime, documentation of treated areas will help distinguish between new veins and recurrent veins. Finally, some patients with longstanding varicose veins have hyperpigmentation around the varicosity. Preoperative photographic documentation is thus important (see Chapters 9 and 12).

Rocha et al evaluated the use of digital photography in combination with a computer program to assess the degree of clearance of telangiectasias during sclerotherapy treatment.19 Photographs were taken using a digital camera (Olympus D-600 L, Olympus Imaging America Inc., Melville, N.Y.) with a resolution of 1280 × 1024 pixels. Before and after images were subsequently analyzed by two methods, the first being an analysis of projected images by physicians with sclerotherapy experience, and the second being an analysis of images by a computer program designed at the Electrical Engineering and Computation University of Campinas, Brazil. This computer program allowed automatic detection of telangiectasias, quantifying them by color and morphology, and using pixel computations to calculate the percentage of telangiectasia in the pre-and post-treatment images. The program then computed the percentage variation in telangiectasias between the two photographs. Computer clearance rates showed a statistically significant correlation with those made via physician assessments, which supports the potential value of this computer program.

Patient Informational Brochures

To educate patients about sclerotherapy, it is best for the physician to produce a brochure or information sheet that incorporates his or her unique and personalized approach to such treatment. There is no totally right way to perform sclerotherapy, and there are relatively few absolutes regarding preoperative preparation, treatment, and postoperative instructions. However, to produce personalized brochures is expensive. As an alternative, a number of ready-made commercial brochures are available (![]() see online Appendix D). One particularly valuable patient education pamphlet that provides information on the etiology as well as the treatment of varicose and spider veins is available through the American College of Phlebology.20

see online Appendix D). One particularly valuable patient education pamphlet that provides information on the etiology as well as the treatment of varicose and spider veins is available through the American College of Phlebology.20

Insurance Reimbursement

Many physicians have expressed frustration in their attempt to obtain insurance reimbursement for the treatment of varicose veins with compression sclerotherapy, even though the veins are symptomatic. Coverage is usually limited to patients who have complications that can be attributed to their underlying venous disease. For example, patients with lifestyle-altering symptomatic venous disease which does not respond to conservative therapy as well as those with concommitant phlebitis, ulceration, or cellulitis are more likely to have insurance that covers varicose vein treatment then those who are asymptomatic. However, even those with symptomatic venous disease can experience trouble obtaining treatment reimbursement from insurance companies until they fail a trial of conservative therapy (extremity elevation, daily use of compression stockings, and exercise for 3 to 6 months).12 From a limited review of insurance reimbursement in our practice, the amount of reimbursement varies markedly, not only between different insurance companies but also within the same insurance company from patient to patient, as well as for the same patient from one treatment to the next. The reimbursement problem has become so illogical and costly that we have not billed insurance companies for treatment since 1992. In 2008, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released a new Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFA), which resulted in decreased Medicare reimbursement for vein procedures performed in the non-facility setting.21 Specifically, Medicare reimbursement for vascular ablation as well as sclerotherapy fell by almost 15% and 5%, respectively. For the most up-to-date Medicare fee schedule information, the reader is encouraged to visit the CMS website at www.cms.hhs.gov/PhysicianFeeSched/PFSFRN/list.asp.

Most physicians do not submit bills for insurance reimbursement charges for treating purely cosmetic veins. However, some of my colleagues correctly point out that what is perceived as cosmetic by the patient is in reality a normalization of cutaneous blood flow and thus, strictly speaking, not cosmetic. In addition, many providers use CPT codes in the 17000 series, indicating destruction of benign lesions for this treatment. Although one may be able to defend this practice, we believe using the 17000 codes only serves to further confuse representatives of insurance companies and may result in furthering a distrust between the insurance carrier and the sclerotherapist. It is our belief that those who perform sclerotherapy should use the sclerotherapy code; when reimbursement is less than adequate, the insurance claim should be petitioned and the company should be properly educated about the cost-effectiveness of sclerotherapy. With this direction, the NASP (now ACP) produced a ‘White Paper’ on sclerotherapy that was sent to more than 600 insurance carriers in 1992.22 This paper was produced as an aid to the physician when submitting bills for reimbursement and to educate the insurance company. It defines phlebology, sclerotherapy, and surgical treatments, discusses symptomatology and the medical necessity for treatment of the defined disease, and concludes with guidelines for determination of medical necessity. Not one insurance company representative responded to this document even after numerous follow-up letters.

Many methods have been used by practitioners to educate insurance companies on the technique of compression sclerotherapy. Some of us send the insurance companies detailed operative reports with or without summaries of the history of compression sclerotherapy and the cost-effective nature of this treatment versus surgical ligation and strippings. However, this attempt, despite being time consuming for the physician, is often met with indifference on the part of insurance companies. Thus, each physician must make an individual decision regarding insurance reimbursement. Box 15.1 lists insurance codes for various diagnostic, testing, and treatment services in sclerotherapy.

Box 15.1 Diagnosis (ICD-9) and procedure (CPT) codes for various sclerotherapy services*

Diagnostic

| Spider veins | 448.1 |

| Elective/cosmetic procedure | V50.1 |

| Varicose veins | 454.9 |

| Varicose vein with inflammation | 454.1 |

| Leg pain | 729.5 |

| Leg edema | 782.3 |

| Leg ulcer, chronic | 707.1 |

| Chronic venous insufficiency | 459.81 |

| Thrombophlebitis, leg | 451.2 |

| Hematoma complicating a procedure | 998.12 |

| Lymphedema | 457.1 |

Noninvasive testing

| Doppler venous – unilateral | 93965 |

| Doppler venous – bilateral | 93965-50 |

| Doppler arterial | 93922 |

| Duplex examination – unilateral or limited | 93971 |

| Duplex examination – bilateral, complete | 93970 |

| Photoplethysmography – unilateral | 93965 |

| Photoplethysmography – bilateral | 93965-50 |

Sclerotherapy treatment

| Cosmetic procedure | A9370 |

| Spider – face | 36469 |

| Spider – non-face | 36468 |

| Varicose vein – single unilateral | 36470 |

| Varicose vein – single bilateral | 35470-50 |

| Varicose vein – multiple unilateral | 35471 |

| Varicose vein – multiple bilateral | 35471-50 |

| Endovenous ablation (radiofrequency) of incompetent vein, extremity; first vein treated | 36475 |

| Endovenous ablation of second and subsequent veins in single extremity | +36476 |

| Endovenous ablation (laser) of incompetent vein, extremity; first vein treated | 36478 |

| Endovenous ablation of second and subsequent veins in single extremity | +36479 |

| Sclerotherapy tray | A4550 |

| Sodium tetradecyl sulfate | J3490 |

| Compression bandages | A4460 |

| Compression stockings – knee high | A4500 |

| Compression stockings – thigh high | A4495 |

| Puncture aspiration of hematoma | 10160 |

A detailed discussion of insurance reimbursement for endovenous treatment of truncal veins is found online in Appendix H![]() .

.

1 Butie A, Goldman MP. Preliminary results from the North American Society of Phlebology membership questionnaire. Newsletter North Am Soc Phlebol. 1988;2:3.

2 Food and Drug Administration: Communication under the Freedom of Information Act, 1990.

3 Marston WA, Brabham VW, Mendes R, et al. The importance of deep venous reflux velocity as a determinant of outcome in patients with combined superficial and deep venous reflux treated with endovenous saphenous ablation. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:400.

4 Van den Bos R, Arends L, Kockaert M, et al. Endovenous therapies of lower extremity varicosities: a meta-analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:230.

5 Hallgren R, Fry PD, Goldman MP. The current and future role of the nurse in phlebology: the Canadian experience. Dermatol Nurs. 1993;5:60.

6 GE Healthcare, Society for Vascular Ultrasound, American College of Phlebology. Lower extremity superficial venous exam DVD. GE Healthcare in conjunction with Society for Vascular Ultrasound and American College of Phlebology, Wauwatosa, Wis www.svunet.org, 2009.

7 Bergan JJ, Cheng V. Foam sclerotherapy: a textbook. London, UK: Royal Society of Medicine Press; 2008.

8 Goldman MP, Georgiev M, Ricci S. Ambulatory phlebectomy: a practical guide for treating varicose veins, 2nd ed. Boca Raton, Fla: Taylor & Francis; 2005.

9 Weiss RA, Feied CF, Weiss MA. Vein diagnosis and treatment: a comprehensive approach. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001.

10 Zwiebel W, Pellerito J. Introduction to vascular ultrasonography, 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2005.

11 Passman MA, Dattilo JB, Guzman RJ, et al. Impact on physician workload and revenue following the creation of a specialty vein clinic within an academic vascular practice. Phlebology. 2007;22:70.

12 Shortell CK, Markovic JN. Incorporating outpatient venous procedures into a vascular surgery practice. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50:225.

13 Labropoulos N, Leon LRJr. Duplex evaluation of venous insufficiency. Semin Vasc Surg. 2005;18:5.

14 Epstein E. Magnifiers in dermatology: a personal survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:687.

15 Rucker M, Beattie C, McGregor C, et al. Declination angle and its role in selecting surgical telescopes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;130:1096.

16 Chaffin DB. Localized muscle fatigue: definition and measurement. J Occup Med. 1973;15:346.

17 Siegel DM. The precision binocular loupe. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1989;15:388.

18 Ganguli S, Tham JC, Janne d’Orthee BM. Establishing an outpatient clinic for minimally invasive vein care. Am J Roentgenol. 188, 2007.

19 Rocha EF, Filho JP, Alencar RDE, et al. Quantitative analysis of sclerotherapy results by using digital photography and a computer program. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:902.

20 American College of Phlebology. Treatment of varicose and spider veins. San Leandro, Calif.: American College of Phlebology; 2008.

21 Hickey J. 2009 Medicare fee schedules. Endovenous Laser Reimbursement News. 2008;8:3.

22 Weiss RA, Haegle CR, Raymond-Martimbeau P. Insurance Advisory Committee report. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:609.

-inch length as either a Yale (Becton, Dickinson) hypodermic needle or as an allergy needle–syringe combination fixed to a 1-mm syringe. The benefit of using the 1-mm syringe is the ease of handling perceived by some sclerotherapists. The Yale 26-gauge needle also comes in a

-inch length as either a Yale (Becton, Dickinson) hypodermic needle or as an allergy needle–syringe combination fixed to a 1-mm syringe. The benefit of using the 1-mm syringe is the ease of handling perceived by some sclerotherapists. The Yale 26-gauge needle also comes in a  -inch length and has the advantage of a sturdy, nonbendable shaft. In short, all types have their advantages and disadvantages. The best needle is the one with which the physician is most comfortable.

-inch length and has the advantage of a sturdy, nonbendable shaft. In short, all types have their advantages and disadvantages. The best needle is the one with which the physician is most comfortable. inch, and the tubing is 30 cm. The plastic tubing on the proximal end of the needle allows visualization of arterial versus venous flow without risking blood exposure. The tubing takes up 0.41 mL of fluid. Some physicians fill the needle tubing with sclerosing solution to prevent clotting of blood within the needle tubing. However, this is unnecessary if the injection is performed within a few minutes of blood aspiration.

inch, and the tubing is 30 cm. The plastic tubing on the proximal end of the needle allows visualization of arterial versus venous flow without risking blood exposure. The tubing takes up 0.41 mL of fluid. Some physicians fill the needle tubing with sclerosing solution to prevent clotting of blood within the needle tubing. However, this is unnecessary if the injection is performed within a few minutes of blood aspiration. -inch needle on a short (

-inch needle on a short ( -inch) catheter tubing. The priming volume with this short length is 0.05 mL. The female Luer-Lok connector has a flange for easy grip. STD Pharmaceuticals (Hereford, UK) have a 30-gauge needle set with the needle attached to the tubing without wings and the other end of the tubing connected to a standard clear plastic female Luer-Lok [0].

-inch) catheter tubing. The priming volume with this short length is 0.05 mL. The female Luer-Lok connector has a flange for easy grip. STD Pharmaceuticals (Hereford, UK) have a 30-gauge needle set with the needle attached to the tubing without wings and the other end of the tubing connected to a standard clear plastic female Luer-Lok [0].