12 Sequencing the content and the spiral curriculum

The importance of sequencing

• The arrangement of courses in a specific order. Prerequisites for one course may include the learning outcomes achieved in an earlier course. The order of courses can help students to organise meaningful patterns in the vast amount of content knowledge so that they are less likely to forget what they have learned and are able to apply knowledge to new problems or unfamiliar contexts. The earlier introduction in the curriculum of clinical experiences provides students with a context for their learning.

• Establishing the connectivity and interdependence of courses. Students should be assisted in identifying connections between what they are currently learning, what they have previously learned, and what they have still to learn.

Guidelines for sequencing

Of prime consideration in the sequencing of courses are:

• The prerequisites. The knowledge or skills that the students need before entering the course.

• The course content. What the students are required to study to master the expected learning outcomes.

• Application of the competencies gained. Students’ continued learning following the course.

1. The logical ordering of content that is already obvious to a subject specialist is not necessarily the most appropriate way for a student to learn the subject.

2. The prime aim in ordering the content of a course is to help students to learn most effectively. The introduction of students to patients in the early years of the course leads to better learning of the basic medical sciences.

Progression

Four dimensions can be considered in relation to students’ progression through the curriculum (Harden 2007):

1. Increased breadth. As they progress through the programme, the learners can extend their area of competence to new topics and to different practice contexts. In clinical medicine, for example, they can learn about heart murmurs not previously considered and learn about this aspect of medicine as applied to children as distinct from adults.

2. Increased difficulty. Students can progress by gaining a greater understanding through addressing a learning outcome in more depth. They may learn more about the pathogenesis of a disease or be able to interpret an atypical example of a cardiac murmur already studied.

3. Increased utility and application to practice. Students can progress from a more theoretical understanding of a subject to its application in medical practice. In the early years students may practise communication skills with their colleagues or with simulated patients. In the later years they move on to communicate with patients in a range of clinical settings, at first supervised and later unsupervised.

4. Increased proficiency. Students may demonstrate increased proficiency in an area associated with more efficient and effective performance. This may be exemplified by less time required for a clinical task or the achievement of higher standards with fewer errors.

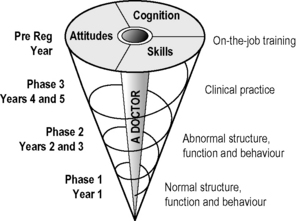

A spiral curriculum

• Topics are revisited. Students revisit topics, themes or subjects on a number of occasions during a course. A body system such as the cardiovascular system may be studied in the early years and again at a later stage in the curriculum.

• There are increasing levels of difficulty. The topics visited are addressed in successive levels of difficulty. Each return visit has added learning outcomes and presents fresh learning opportunities to help the student work towards the final learning outcomes.

• New learning is related to previous learning. New information or skills introduced are related back and linked directly to learning in previous phases of the spiral. For example a cardiovascular system course in year 3 of a curriculum will build on the understanding of normal structure and function achieved in the cardiovascular course in year 1. In a third loop in the

spiral in the final year, students have the opportunity to study cardiovascular problems in the context of patients they see in their clinical attachments.

• Competence of students increases. The learner’s competence increases with each visit until the final learning outcomes are achieved.

Reflect and react

1. Think of your own course in the context of a spiral curriculum. Does it help students to build on what they already know? What will your course add?

2. If students fail to master the learning outcomes for your course, is there a remediation plan in place to help them before they move on to the next phase of their training?

3. Is there a need for an orientation or transitional course between your own course and what precedes or follows it?

Dornan T., Littlewood S., Margolis S.A., et al. How can experience in clinical and community settings contribute to early medical education? A BEME systematic review. BEME Guide No. 6. Med. Teach.. 2006;28:13-18.

The rationale for the early introduction of clinical experience in the medical curriculum.

Harden R.M. Learning outcomes as a tool to assess progression. Med. Teach.. 2007;29:678-682.

Harden R.M., Stamper N. What is a spiral curriculum? Med. Teach.. 1999;21:141-143.

A description of the concept of a spiral curriculum.

Harden R.M., Davis M.H., Crosby J.R. The new Dundee medical curriculum: a whole that is greater than the sum of the parts. Med. Educ.. 1997;31:264-271.