Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy

Dye/Radiotracer and Injection Sites

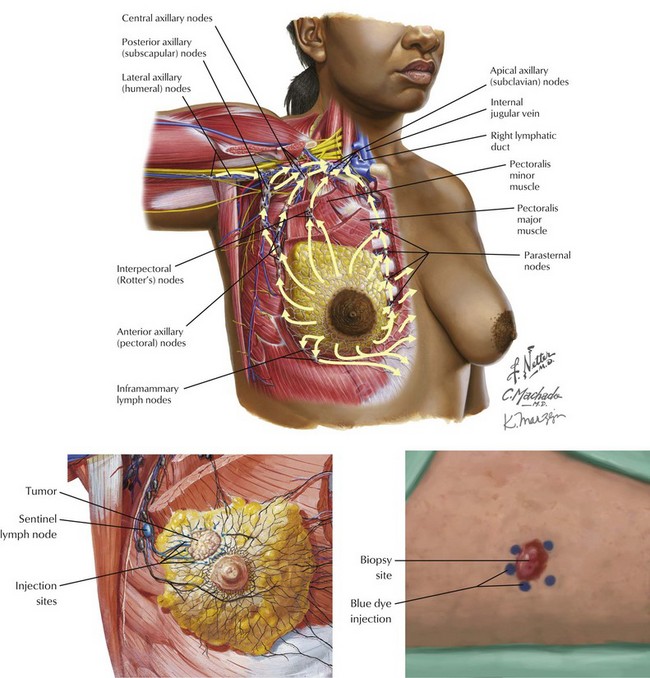

The injection site for the blue dye or the radiotracer can be either over the tumor or the areola (Fig. 48-1). In the operating room the surgeon then looks for a blue lymph node (if dye is used), a radioactive lymph node (if radiotracer is used), or both. With a radiotracer, multiple nodes may be radioactive. It is important to search for the node with the highest level of radioactivity. This node, as well as all nodes with more than 10% of the highest count, should be removed for pathologic evaluation.

Lymphatic Drainage

Another important consideration is the choice of injection site. The lymphatic drainage of the breast and overlying skin are the same: both drain to the axillary lymph nodes. Therefore, intradermal injection (vs. peritumoral injection) of radiotracer is an acceptable practice. Periareolar and subareolar injections work equally well for SLNB. However, intradermal injection of blue dye may lead to skin discoloration and should be avoided in breast cancer. This approach contrasts with melanoma, in which intradermal injections are required; the discoloration of the skin is irrelevant because a wide local excision will be performed at the time of SLNB (Fig. 48-1).

Lesion Drainage to Lymph Nodes

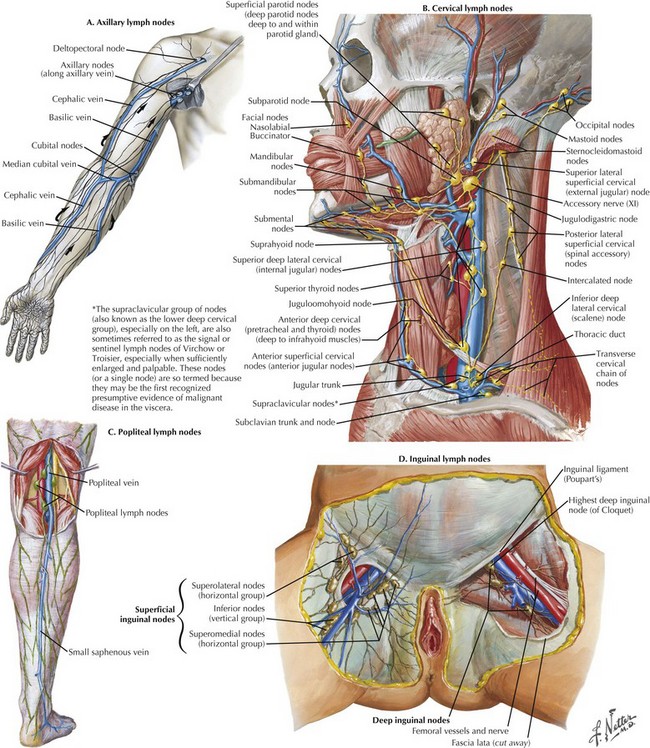

Unlike breast cancer, the variable locations of cutaneous melanoma lead to SNLB being performed in multiple locations. Typically, upper-extremity melanoma will drain to the axillary lymph nodes, although epitrochlear lymph nodes may also contain the sentinel node in distal tumors (Fig. 48-2, A). Lesions of the scalp typically drain to the posterior cervical lymph nodes, whereas lesions of the face and oral cavity usually drain to the anterior cervical lymph nodes (Fig. 48-2, B). Lower-extremity tumors can drain into the popliteal or inguinal node basins (Fig. 48-2, C and D).

Identification of the Sentinel Lymph Node

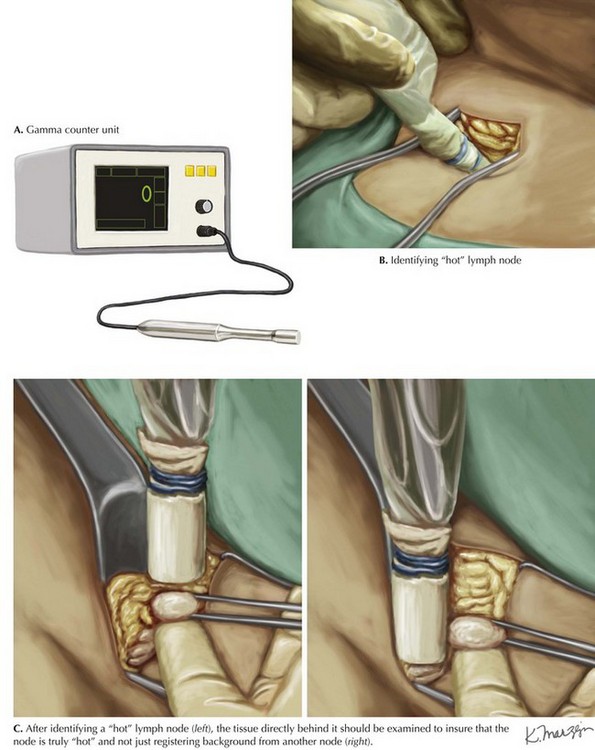

After entering the approximate area of the sentinel node, the surgeon begins localized dissection. If blue dye is used, careful dissection is performed until a blue node is discovered. If radiolabeled colloid is used, a gamma probe will guide the dissection (Fig. 48-3, A).

After identifying a “hot” lymph node (Fig. 48-3, B), the surgeon should examine the tissue directly behind it to ensure that the node is truly hot and not just registering background from another node (Fig. 48-3, C).

Ashikaga, T, Krag, DN, Land, SR, et al. Morbidity results from the NSABP B-32 trial comparing sentinel lymph node dissection versus axillary dissection. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102(2):111–118.

Bagaria, SP, Faries, MB, Morton, DL. Sentinel node biopsy in melanoma: technical considerations of the procedure as performed at the John Wayne Cancer Institute. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101(8):669–676.

Kelly, TA, Kim, JA, Patrick, R, Grundfest, S, Crowe, JP. Axillary lymph node metastases in patients with a final diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ. Am J Surg. 2003;186(4):368–370.

Krag, DN, Anderson, SJ, Julian, TB, et al. Sentinel-lymph-node resection compared with conventional axillary-lymph-node dissection in clinically node-negative patients with breast cancer: overall survival findings from the NSABP B-32 randomised Phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(10):927–933.

Lynch, MA, Jackson, J, Kim, JA, Leeming, RA. Optimal number of radioactive sentinel lymph nodes to remove for accurate axillary staging of breast cancer. Surgery. 2008;144(4):525–531.

Menes, TS, Schachter, J, Steinmetz, AP, Hardoff, R, Gutman, H. Lymphatic drainage to the popliteal basin in distal lower extremity malignant melanoma. Arch Surg. 2004;139(9):1002–1006.

Sloan, P. Head and neck sentinel lymph node biopsy: current state of the art. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3(3):231–237.