18 Self-Care

The Foundation of Care Giving

The best way to become a better “helper” is to become a better person. But one necessary aspect of becoming a better person is via helping other people. So one must and can do both simultaneously.1

As clinicians come face to face with the inevitable suffering of a child’s dying and death, they have a choice, if not always consciously made, in how they approach their work. When they cope with suffering by seeing themselves as strong and giving to others who are perceived as weak, they are at high risk for burnout, becoming disillusioned and drained of energy. By contrast, if instead of helping the weak and vulnerable, they choose to offer themselves in service, then they assume a role of knowledgeable guide. As a knowledgeable guide they serve others with their whole selves that includes their particular strengths as well as vulnerabilities. Clinicians recognize the dark, the light, and the weak and strong aspects of their being and understand that are all needed in situations of intense suffering. They also recognize that despite their specialized knowledge in some areas, in most areas they share the sense of mystery experienced by those they serve. They can do only what they can, then they must let go of expectations that they can control outcomes that never were within our control. If they perceive their work as offering their whole selves in service, then the necessity to work on themselves becomes apparent. This self-work or self-care is both a requirement of their roles as well as a privilege they are being offered: to be allowed to become more themselves and to move toward their own potential as part of their daily jobs. As Robert Coles said, “I had begun to see how complicated this notion of service is, how it is a function of not only what we do but who we are (which of course, gives shape to what we do).”2

What do care givers have to offer families of children who live with a life-threatening illness? What more can they possibly do or say when all has been done in terms of pain and symptom control? How can each of the care givers be enough in the face of such suffering? They know that what children and parents value during these times is the abiding presence of a trusted person who listens and bears witness to their suffering, even better if that person has experience in being present in similar life-threatening situations, and has walked that path with others.3,4 “All I want is what is in your mind and in your heart,” said dying patient David Tasma to Cicely Saunders, founder of the modern hospice movement. Tasma shared and supported her dream to develop a hospice. The quality of care is not limited to professional expertise but is greatly affected by what each clinician, as individuals and as members of a professional team, brings into relationships with children, adolescents, and parents. While bringing their imperfect selves to the service of others is necessary, it is not, however, sufficient. What is also required is that clinicians care for themselves in an ongoing reflective and systematic way.

The term self-care has been used in a variety of activities and in its most reductive sense is understood superficially as taking time for ourselves or taking a vacation. While it is important to balance work-life with other activities, the kind of self-care that leads to enduring personal resilience and growth requires more than time away because clinicians can never get away from themselves. In the words of Jon Kabat Zinn, “Wherever you go, there you are.”5 Self-care, when stripped of self-reflection, meaning making and paying attention in the present moment, becomes a self-centered exercise that is about I, Me, and Mine. Self-care activities based solely on distractions, such as vacations and other means to get away from work, can become selfish. If distractions and running away, including reliance on drugs and alcohol, are exclusively what self-care consists of, then inevitably there is never going to be enough time away. When the habit of running away from what is in the present moment becomes an established practice, then caregivers find that each distraction is good for a while but inevitably tolerance develops and no time away or distraction is ever enough. It is important to clarify that distraction, in and of itself, is not bad or unhealthy; and when entered into mindfully it is one of many strategies that can be helpful. Rather than being harmful, distraction, in the correct balance, is necessary but not enough to encompass the self-care needed in pediatric palliative care. While eating well, getting adequate sleep, regular medical care, physical exercise, having interests outside work, and making time for oneself are all important and necessary aspects of self-care, they are not sufficient. What follows in this chapter is a focus on the deep work of caring for the caregivers, which is essential when attending to the suffering of others.

Relationship to Self

All of that is possible in the context of relationships that are personal. Personal relationships both make the job highly stressful but also deeply fulfilling, and determine the degree of satisfaction that families experience with regard to the care being offered to them. We have come to understand that the relationships developed with the parents of seriously ill children are often problematic, and professionals who are insensitive, unavailable, or impersonal in their approaches elicit parental dissatisfaction and increased distress.3,6–13 Parental satisfaction with care is directly related to the nature of the relationships held with the care providers. These relationships have a positive or negative impact upon how families experience the dying process and death of a child, and seem to affect their long-term adjustment to loss. These findings make self-reflective practice a necessary part of the job, and encourage caregivers to review the relationships developed as well as challenge some of the mistaken beliefs according to which specialized knowledge, refined skills, and clinical experience are thought to be enough to ensure quality of care. While knowledge, skills, and experience are undoubtedly critical, families of seriously ill children demand more than that and expect a personal, human, and caring relationship. The following example illustrates how quality of care extends beyond the provision of expert care, and encompasses the development of nurturing and meaningful relationships with children and parents.

A Relationship-Centered Approach to Care

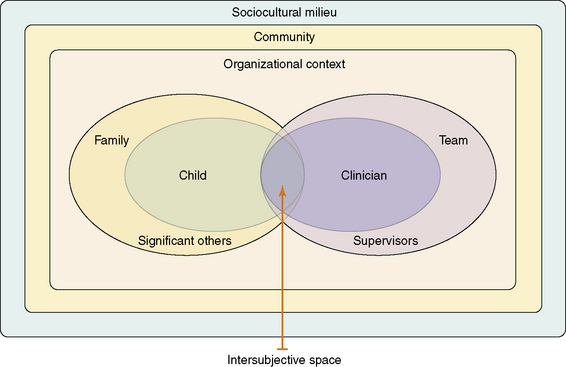

Papadatou14 suggests that it is necessary to expand our view of the care of seriously ill children beyond the family-centered approach that limits focus to the needs, concerns, and preferences of young patients and their families. This broader outlook is possible if a relationship-centered approach is adopted. Such an approach illuminates the dynamics that develop in life-and-death situations among patients, family members, professionals, and teams, and considers the larger organizational and sociocultural contexts in which care is offered and received. It explores the reciprocal influence of patients, families, and professionals and sheds light upon their subjective experiences and interactions in the context of healthcare.15 In essence, the relationship-centered approach focuses on whatever transpires when the private and social worlds of a sick child or family interacts with the private and social worlds of care providers in a given work and social environment. To better understand the outcomes of such encounters, it is important to consider its basic components (Fig. 18-1):

According to Stern,16 the intersubjective space is “the domain of feelings, thoughts, and knowledge that two (or more) people share about the nature of their current relationship” (p. 243). When the clinician and the patient or parent are open to each other, and to their respective worlds, then the intersubjective space is enlarged to include a rich partnership, a fruitful collaboration, and the co-creation of new narratives. It also includes opportunities for increased self-awareness, new learning, positive changes, and personal growth in the midst of uncertainty and hope. Such experiences render the process of care human, meaningful, and rewarding. By contrast, when both clinicians and family members enact prescribed roles and focus solely on what needs to be done, which is often accomplished in a ritualistic or detached manner—then the intersubjective space becomes limited in its capacity to offer opportunities for genuine connection. It is also limited for viewing reality in a new way, and for containing, tempering, and transforming suffering in meaningful ways while developing resilience in the midst of adversity and loss.

The Private Worlds of Professionals

These beliefs prevent clinicians from developing caring relationships in which they are fully present and aware of what unfolds in the intersubjective space that is shared between themselves and others. As caregivers, knowing oneself is equally important as knowing the child, the adolescent, or the family to whom services are provided. Such ‘self-knowledge’ should not be limited to cognitive understanding, but also includes the integration of information gathered from emotional responses, physical senses, and bodily reactions, all of which contribute to self-understanding. When caregivers accompany families through illness, dying, and bereavement they cannot promise a cure, a perfect death, or recovery from bereavement. All they can assure is a committed and authentic relationship in which they will strive to remain fully present and open to the child’s and family’s experiences, no matter how painful or distressing these may be. According to Papadatou14 such openness “permits us to meet the unknown in life, in others, or in ourselves without preconceived ideas or rigid theories and planned interventions. It allows us to welcome the unexpected without always trying to provide a logical explanation, and to work through the paradoxes that are inherent in life and death situations.… This process demands time, energy, and commitment. When we are consumed by the everyday and rush from one activity, task, or crisis to the next, we do not engage in a deep examination of our experiences and we restrict our capacity to provide effective care and to reap the rewards.”

When caregivers remain open and vulnerable enough, they acknowledge the presence of death in all relationships and cope with its effects upon patients, families, teams, and themselves. Only then may they recognize its violent impact upon relationships which are threatened, broken, or severed forever, as well as its vitalizing force that motivates families to live more fully and confronts us with life’s value and meaning.14,17

What are some aspects of caregivers suffering?

Suffering That Leads to Impairment

Burnout is a “state of physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion caused by long-term involvement in emotionally demanding situations.”18 Although described as a static state, burnout is more of a process that develops gradually, when:

Burnout is worsened by not coping adequately with these emotional responses or taking the necessary time to process experiences, review goals, and recharge batteries by addressing the need for self care. Sometimes burnout stems from the long-term effects of caring for others, called caring burnout. At other times it is from becoming disillusioned and losing a sense of purpose and meaning in the care provided, called meaning burnout, either because the job becomes routine, boring or insignificant, or because caregivers doubt the value or effectiveness of the work.19 The key dimensions of burnout involve emotional exhaustion, a depersonalized approach toward patients and detachment from the job, and a sense of incompetence and lack of achievement.20 Although the term burnout is used quite casually in the workplace, it is important to recognize that it is a severe psychological condition that is often associated with depressive symptoms, anxiety, and demoralization.

Other times, however, caregivers’ suffering occurs suddenly in situations that we experience as highly traumatic. Faced with the trauma of others, we experience compassion stress, which is defined as “the natural consequent behaviours and emotions… resulting from helping or wanting to help a traumatized or suffering person.”21 Figley argues that when caregivers are not satisfied with the help provided, and fail to reduce the suffering of traumatized people, caregivers experience secondary traumatic stress, compassion stress, which can develop into a secondary traumatic stress disorder that he named compassion fatigue. Symptoms of compassion fatigue are similar to symptoms of a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and can be grouped in three categories:

In reality, compassion fatigue is a disorder that requires professional help.

Suffering That Is Unavoidable

Not all suffering is hazardous to caregivers’ well-being and to the quality of their work. Some of their distress to the pain and suffering of seriously ill or dying children, and grieving parents, is unavoidable (Fig. 18-2). Not infrequently it reflects a grieving process over losses that are experienced in acute or chronic life-and-death situations.22–26 Papadatou14 offers a model that describes the healthy, unavoidable grieving process triggered by an event or situations that are perceived as losses. For example, some clinicians experience as loss the death of a child and grieve over a special bond that has been severed forever; others experience as loss the non-realization of professional goals to cure a child; still others grieve over personal loss that surfaces with exposure to a child’s death. Most often such losses trigger a grieving process that presents unique characteristics. It involves an ongoing fluctuation between experiencing grief responses, and avoiding or repressing them. This fluctuation enables clinicians to acknowledge their losses but also set them aside in order to function appropriately without being overwhelmed. Moving in and out from grief helps to attribute meaning to their experiences with regard to the dying process and death of a patient, as well as to their roles and contributions in the care of families of seriously ill children.

What Are Some of the Rewards?

Rewarding experiences have several sources (Fig. 18-3). Sometimes they are associated with the outcomes of caregivers’ interventions, the achievement of a desired goal, the accomplishment a specific task, or the effective management of a challenging situation. While the ultimate goal in pediatric palliative care is to enhance the quality of life of seriously ill children and of their family members by attending to their physical, psychosocial, and spiritual needs, the criteria that define quality of life are often vague and subjective because they vary among patients and families. At times the goals that, according to one set of values enhance quality of life do not coincide with the priorities of families who strive for a cure, the prolongation of life even when its quality is seriously compromised, or hope for a miracle. Unfortunately, in pediatric palliative care, what families desire most, the cure of their child, cannot be provided. This explains why the rewards caregivers derive are most often associated with the process by which services are provided. They involve, for example, the establishment of caring relationships or bonds; an availability, presence, and compassion through the diagnosis, illness, or dying trajectory; the creativity and resourcefulness by which caregivers respond to needs; or the fruitful collaboration with co-workers in the pursuit of shared goals.

Rewards are profound when caregivers find value and attribute meaning to a job that is well done and contributes to the fulfillment and growth of others, whose lives are positively affected. Caregivers derive meaning from assisting families in coping with major challenges and, despite their suffering, sometimes live peak experiences that function as a source of comfort after the child’s death. Such peak experiences are uncommon experiences that are experienced as intensely meaningful or highly significant and unforgettable and are usually associated with feelings of awe, wonder, connection, and love.27

When caregivers value their services, they pass their knowledge and seek to affect others by sharing their experiences and wisdom. Caregivers experience what Yalom28 describes as ”rippling.” Through actions that are not aimed at fame, prestige, or self-elevation, but rather toward a social good, caregivers create multiple concentric circles of influence that effect, oftentimes without their conscious knowledge, the lives of others for years and generations.

Rewards in Palliative Care

Finally, rewards in palliative care are associated with a sense of personal growth that may be experienced at various levels14:

Growth Associated with Life Perspective

Life is not perceived superficially, but valued and lived with increased awareness. Caregivers reflect upon their personal goals and priorities and actively strive to live a life that is enriching to them and their loved ones. Frequent reminders of their own mortality encourage them to review their own lives, imagine their ultimate end, and contemplate the finality of valued relationships. Despite the anxiety that such a process engenders, it usually becomes an awakening experience through which caregivers can change unfulfilling lives, or cope with regrets over missed opportunities and any sense that life has slipped away. Through this process caregivers develop new perceptions of who they are, make new choices over what is important to strive for, and feel free to live differently.28

To experience the rewards of care giving in pediatric palliative care, caregivers must first be willing to illuminate what Jellinek29 described as the “dark side” of caring for seriously ill children. That involves an acceptance of a suffering that is inevitable when life is threatened and caring bonds are severed by death. This demands a willingness to create the space and time to reflect over caregivers’ work experiences in order to better understand how they affect and are being affected by the children and parents served. It also requires that caregivers explore the meaning they attribute to their experiences, to personal issues that compromise the care provided, and to identify those resources that help them do a good enough job.

However, caregivers must keep in mind that this process is not solely an individual affair. Their suffering and rewarding experiences in pediatric palliative care are also affected by professional, social, and cultural variables. As long as the education of physicians and nurses reinforces a biomedical approach to care and socializes future clinicians to maintain a stoic and detached approach toward the suffering of others, then self-awareness and self-care will continue to be discarded as unimportant and remain exclusively a private affair. Moreover, sociocultural values and norms determine how clinicians are expected to cope with death, how they express and manage their grief, what meaning they attribute to patient loss, and what types of support, if any, are available to them. When Greek and Hong Kong pediatric nurses were compared with regard to their responses to the dying process and death of a child, it was found that all experienced a grieving process that remained largely disenfranchised because, in their social contexts, they were expected to be strong and brave in the face of death. However, nurses in these cultures had distinct ways of expressing and coping with their grief.30 Greek nurses displayed their grief openly, cried more frequently, and supported each other within the confines of their unit, which valued and enhanced mutual support. By contrast, Hong Kong nurses were more private and tended to suppress their grief by resorting to practical duties and work responsibilities. Differences were also found when Greek nurses were compared to Greek physicians.31 The latter were more likely to perceive the death of a child as a failure to achieve their professional goals to cure the disease and to prevent death, and reported more avoidant strategies with regard to their grief.

Clinician Suffering and Self-Care

While some clinician suffering may seem inevitable, much unnecessary suffering is caused by specific maladaptive attitudes of the caregiver themselves. Fortunately, once recognized these maladaptive attitudes can be corrected and suffering lessened by practical actions such as mindful practice (Box 18-1). The second part of this chapter offers step-by-step examples of mindful practice skills;32,33 a set of practical, learnable life skills for self-care that serves to reduce or transform suffering in meaningful ways.

BOX 18-1 Suffering in Clinicians

Clinicians can learn to reduce or transform the suffering caused by attachment or the non-acceptance of grief and loss. Moving from suffering toward acceptance is a process that leads to wholeness and healing.38,39

Awareness itself is not a thought, but is more a state of being fully in the present non-judgmentally. Rather than a thought, awareness is a lived experience. The difficulty in conveying mindful awareness lies in the limits of words and their ability to convey concepts better than ideas. Concepts need only words to be understood and communicated while ideas include a component that needs to be experienced if they are to be fully communicated.34 For example while the concept of the physiology of taste can be communicated via words, that is the pathway from taste receptors in the tongue and the neurophysiology of neurotransmitters leading to the sensory cortex, the idea of what a piece of chocolate actually tastes like cannot be effectively communicated by words alone.

The following exercise relates to the awareness of the breath as an example of how to cultivate awareness. What you need for this five-minute exercise is a physical place where you will not be disturbed during the exercise. Read through the instructions in Box 18-2, then simply put the book down for a few minutes and try the exercise for yourself.

BOX 18-2 Five-Minute Seated Awareness Exercise

Reacting versus responding

While a regular practice of between 5 and 30 minutes a day is the mainstay of a regular mindful practice,33 it is also possible to practice mini deliberate moments of active awareness throughout the day. Kearney and colleagues35 have outlined awareness practices that can be incorporated into the caregivers’ workplace, some of which are included in the following list:

Team Care

While the individual clinician needs to establish his or her own self-care practice, working within teams of colleagues presents its own opportunities and challenges. Team dynamics and implicit or explicit rules can promote or negate individual efforts to reduce suffering. In some teams, admissions of individual suffering is perceived as unacceptable, upsetting, and threatening to team functioning. In this environment, clinicians learn to repress and hide their own suffering; they display an outwardly stoic approach to loss and death, and support each other in the suppression of their suffering. This group dynamic of mutual suppression leads to dysfunctional team patterns. By contrast, functional patterns occur when the team’s culture acknowledges individual and collective suffering, and sets as a priority the establishment of a holding environment for its members.14 A holding environment:

Summary

This chapter was conceived as one that would provide background to better understand the need for self-care and its entwined relationship with care giving to those who suffer. Understanding the underlying dynamics in relationships in which patients, family members, and care providers are mutually and reciprocally influenced is not enough to bring about increased awareness, and to that end, the chapter outlines specific awareness self-care practices that infuse conceptual understanding with experiential learning. There are many resources available for developing mindfulness self-care practice in books; on Internet sites such as www.umassmed.edu/Content.aspx?id=41252, in seminars, and workshops.5,36,37 It is also important to be reminded that self awareness and self-care, although inherently individual processes, are developed and enriched through relationships with others. Being open to new understandings and experiences is itself rewarding as we mindfully walk along the path this work offers us.

1 Maslow A.H. Religions, values, and peak experiences. Harmondsworth, Engl. Markham, Ont: Penguin Books, 1976.

2 Coles R. The call of service: a witness to idealism. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1993.

3 Meyer E.C., et al. Improving the quality of end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit: parents’ priorities and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):649-657.

4 Macdonald M.E., et al. Parental perspectives on hospital staff members’ acts of kindness and commemoration after a child’s death. Pediatrics. 2005;116(4):884-890.

5 Kabat-Zinn J. Wherever you go, there you are. London: Piatkus, 2005.

6 Contro N., et al. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(1):14-19.

7 Contro N.A., et al. Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1248-1252.

8 Heller K.S., Solomon M.Z., For the Initiative for Pediatric Palliative Care Investigator. Continuity of care and caring: what matters to parents of children with life-threatening conditions. J Pediatr Nurs. 2005;20(5):335-346.

9 Kreicbergs U., et al. Care-related distress: a nationwide study of parents who lost their child to cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9162-9171.

10 Mack J.W., et al. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9155-9161.

11 Steinhauser K.E., et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2476-2482.

12 Steinhauser K.E., et al. In search of a good death: observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(10):825-832.

13 Solomon M.Z., Browning D. Pediatric palliative care: relationships matter and so does pain control. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9055-9057.

14 Papadatou D. In the face of death: professionals who care for the dying and the bereaved. New York: Springer, 2009;330.

15 Beach M.C., Inui T., Relationship-Centered Care Research. Relationship-centered care: a constructive reframing. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 1):S3-S8.

16 Stern D. The present moment in psychotherapy and everyday life. New York: WW Norton, 2004.

17 Hennezel M. La mort intime. París: Editions Robert Laffont SA, 1995.

18 Pines A., Aronson E. Career burnout: Causes and cures. New York: Free Press, 1988.

19 Skovholt T. The resilient practitioner: burnout prevention and self-care strategies for counselors, therapists, teachers, and health professionals. Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2001.

20 Maslach C. Job burnout: new directions in research and intervention. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2003;12(5):189-192.

21 Figley C. Compassion fatigue: psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. J Clin Psychol. 58(11), 2002.

22 Davies B., et al. Caring for dying children: nurses’ experiences. Pediatr Nurs. 1996;22(6):500-507.

23 Hinds P.S., et al. The impact of a grief workshop for pediatric oncology nurses on their grief and perceived stress. J Pediatr Nurs. 1994;9(6):388-397.

24 Kaplan L.J. Toward a model of caregiver grief: nurses’ experiences of treating dying children. Omega: J Death Dying. 2000;41(3):187-206.

25 Rashotte J., Fothergill-Bourbonnais F., Chamberlain M. Pediatric intensive care nurses and their grief experiences: a phenomenological study. Heart Lung. 1997;26(5):372-386.

26 Shanfield S.B. The mourning of the health care professional: an important element in education about death and loss. Death Educ. 1981;4(4):385-395.

27 Clarke-Steffen L. The meaning of peak and nadir experiences of pediatric oncology nurses: secondary analysis. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 1998;15(1):25-33.

28 Yalom I.D. Staring at the sun: overcoming the terror of death. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2008.

29 Jellinek M.S., et al. Pediatric intensive care training: confronting the dark side. Crit Care Med. 1993;21(5):775-779.

30 Papadatou D., Martinson I.M., Chung P.M. Caring for dying children: a comparative study of nurses’ experiences in Greece and Hong Kong. Cancer Nurs. 2001;24(5):402-412.

31 Papadatou D., et al. Greek nurse and physician grief as a result of caring for children dying of cancer. Pediatr Nurs. 2002;28(4):345-353.

32 Epstein R.M. Mindful practice. JAMA. 1999;282(9):833-839.

33 Kabat-Zinn J., C.W. University of Massachusetts Medical. Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York,: Delta Trade Paperbacks, 2005.

34 Hutchinson T.A., Dobkin P.L. Mindful medical practice: just another fad? Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(8):778-779.

35 Kearney M.K., et al. Self-care of physicians caring for patients at the end of life: “Being connected… a key to my survival,”. JAMA. 2009;301(11):1155-1164. E1

36 Tedeschi R., Calhoun L. Trauma and transformation: growing in the aftermath of suffering. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications, 1995.

37 Halifax J., Byock I. Being with dying: cultivating compassion and fearlessness in the presence of death. Boston: Shambhala Publications, 2008.

38 Kearney M. A place of healing: working with suffering in living and dying. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

39 Mount B.M., Boston P.H., Cohen S.R. Healing connections: on moving from suffering to a sense of well-being. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33(4):372-388.