Chapter 26 Selective Percutaneous Posterolateral Endoscopic Lumbar Nuclectomy

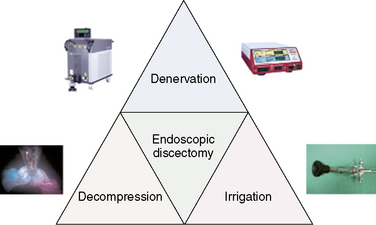

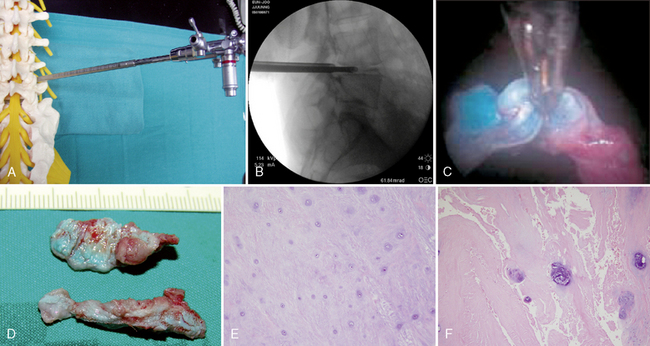

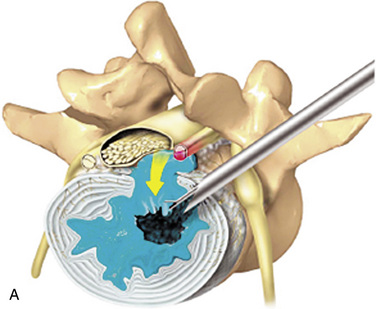

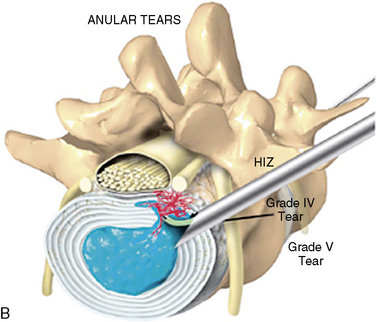

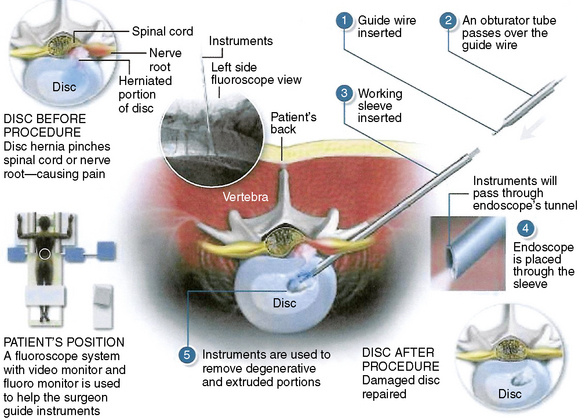

The three distinct mechanisms for pain relief by selective percutaneous posterolateral endoscopic lumbar discectomy are a manageable bulk decompression under direct endoscopic visualization and fluoroscope guidance, dilution of inflammatory peptides through continuous irrigation, and denervation of ingrown nerves by means of radiofrequency and laser (Fig. 26-1).

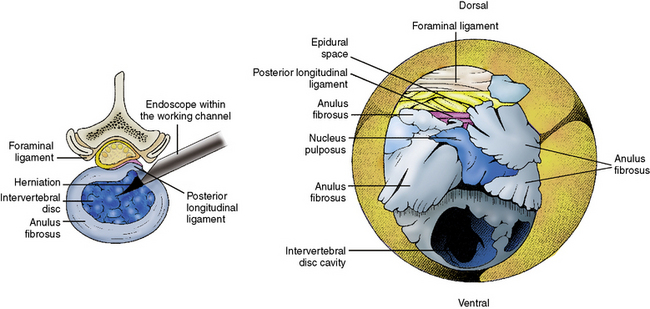

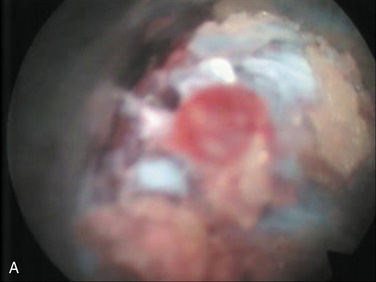

Selective chromoendoscopy (Table 26.1) in spine surgery is based on using the specific indicator (a blue color) of indigo carmine that is highly reactive with acidic extracellular matrix in degenerated nucleus pulposus. There is strong evidence for the usefulness of applying indigo carmine for selective endoscopic intervertebral nuclectomy in degenerated nucleus. However, there is no strict difference between normal aging and degeneration in the intervertebral disc (IVD), and an acidic condition of the IVD does not always indicate a pathologic condition. Removal of all blue-colored nucleus pulposus ensures the removal of all degenerated nucleus pulposus, whether or not the IVD is pathologically degraded. To remove the neural compression of herniated nucleus, decompression must become the primary purpose. Therefore, selective nuclectomy must be performed only when the targeted herniated nucleus turned blue in the posterior third of the IVD during chromoendoscopy.

Table 26.1 Concept of Selective Percutaneous Posterolateral Endoscopic Lumbar Nuclectomy

| Selective | Blue-stained degenerated acid nucleus pulposus |

| Percutaneous | A small incision, not open |

| Posterolateral | Minimization of muscle trauma, with passage through the intervertebral foramen |

| Endoscopic | Under direct visualization |

| Nuclectomy | Targeted third of posterior herniated nucleus under fluoroscopic guidance |

Indications

Selective percutaneous posterolateral endoscopic lumbar nuclectomy is indicated (1) in patients who are experiencing an intractable pain unresponsive to epidural steroid injection, to remove an inflammatory component of discogenic pain, and (2) for decompression of a compressed neural component (Box 26.1).

Complications

The informed consent discussion with the patient should include the following possible complications and their management (Table 26.2):

The surgeon may be unable to access the involved area owing to a high iliac crest, especially in men, or because of an extremely narrow intervertebral disc space. This situation is rare but would require the surgeon to change to an interlaminar approach.

The surgeon may be unable to access the involved area owing to a high iliac crest, especially in men, or because of an extremely narrow intervertebral disc space. This situation is rare but would require the surgeon to change to an interlaminar approach. Transient dysesthesia (sunburn syndrome), lasting about 4 weeks, can be caused by searching for the structures during the approach, or by decompressing and detaching the protruded disc from adhesion with the neural component. Selective dorsal ganglion block and gabapentin medication can be prescribed in these cases.

Transient dysesthesia (sunburn syndrome), lasting about 4 weeks, can be caused by searching for the structures during the approach, or by decompressing and detaching the protruded disc from adhesion with the neural component. Selective dorsal ganglion block and gabapentin medication can be prescribed in these cases. Lumbar plexopathy can be caused by blunt trauma from approaching too close to the midline (within 8 cm). This complication can be prevented by keeping at least 10 cm from the midline. Lumbar plexopathy is verified by electromyography and nerve conduction velocity measurements and is treated with selective dorsal ganglion block and gabapentin medication when necessary.

Lumbar plexopathy can be caused by blunt trauma from approaching too close to the midline (within 8 cm). This complication can be prevented by keeping at least 10 cm from the midline. Lumbar plexopathy is verified by electromyography and nerve conduction velocity measurements and is treated with selective dorsal ganglion block and gabapentin medication when necessary. Superficial or deep-layer hematoma in the can occur in the subcutaneous tissue or between the psoas major and psoas minor muscles, respectively. Compression is necessary for superficial hematoma; observation by magnetic resonance imaging for absorption of blood is required for deep-layer hematoma.

Superficial or deep-layer hematoma in the can occur in the subcutaneous tissue or between the psoas major and psoas minor muscles, respectively. Compression is necessary for superficial hematoma; observation by magnetic resonance imaging for absorption of blood is required for deep-layer hematoma. Further instability can result from the procedure in patients with spondylolisthesis and disc herniation. This instability would be repaired through percutaneous external pedicle screw fixation.

Further instability can result from the procedure in patients with spondylolisthesis and disc herniation. This instability would be repaired through percutaneous external pedicle screw fixation.Table 26.2 Potential Complications, Their Causes, and Their Management

| Potential Complication | Cause(s) | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to access the involved area |

Preoperative prepations

Physical Examination

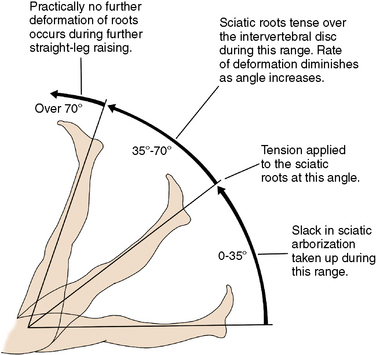

Low back pain upon performance of the straight-leg raising test defines the positive tension sign (essential for diagnosis) (Fig. 26-2).

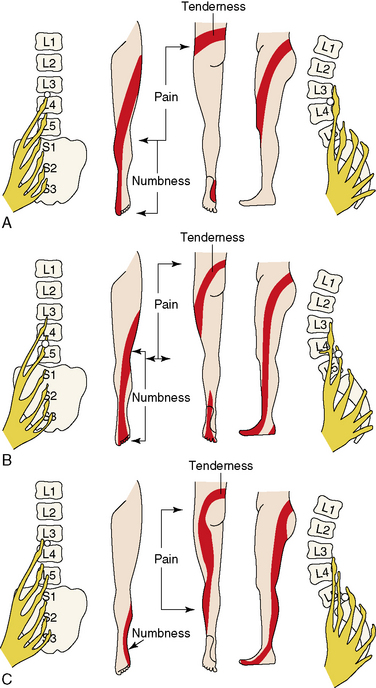

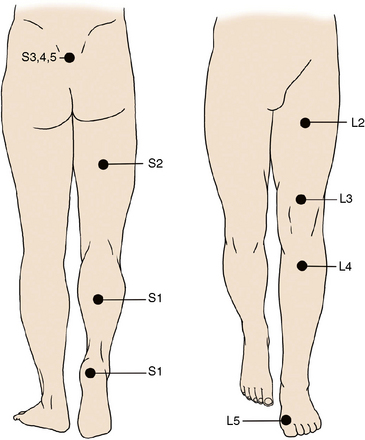

Low back pain upon performance of the straight-leg raising test defines the positive tension sign (essential for diagnosis) (Fig. 26-2). The location of the pain can help localize the nerve root involved. Pain may radiate to small, isolated areas along the course of a dermatome (Figs. 26-3 and 26-4).

The location of the pain can help localize the nerve root involved. Pain may radiate to small, isolated areas along the course of a dermatome (Figs. 26-3 and 26-4).Related anatomy and physiology

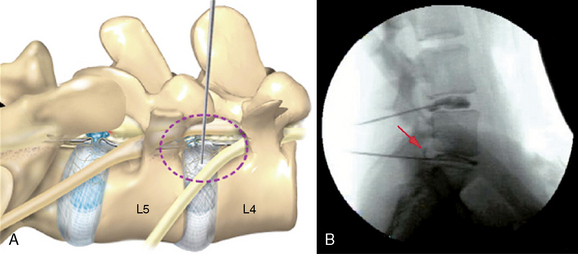

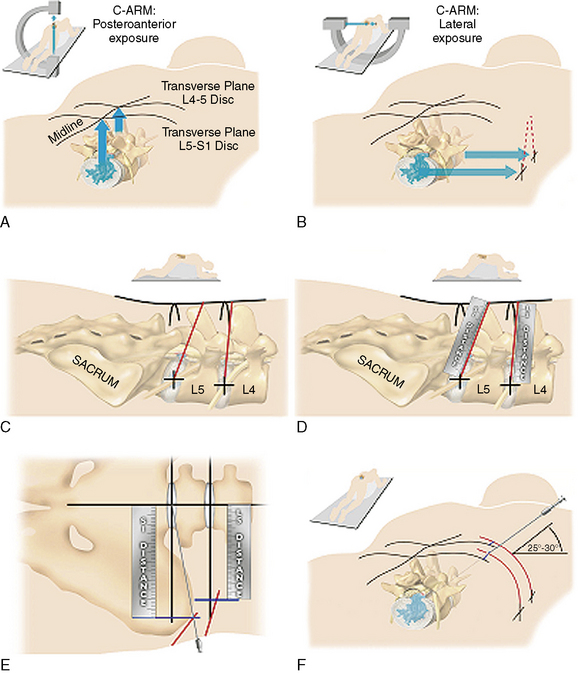

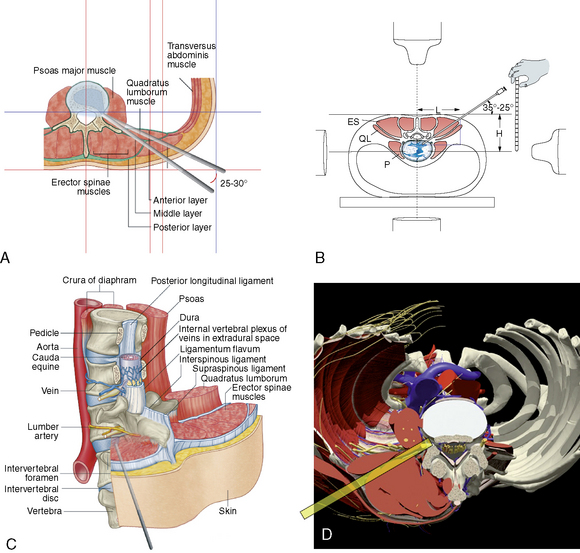

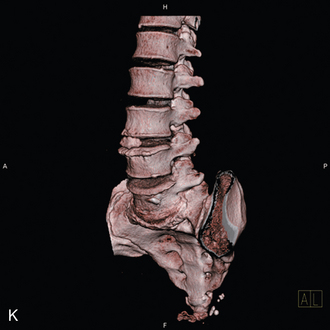

A Kambin’s triangular working zone is the site of surgical access for posterolateral endoscopic discectomy; it is defined as a right triangle over the dorsolateral disc. The hypotenuse is the existing nerve root, the base (width) is the superior border of the caudal vertebra, and the height is the dura and traversing nerve root (Fig. 26-5).

Instrumentation

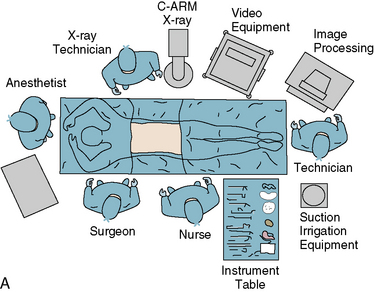

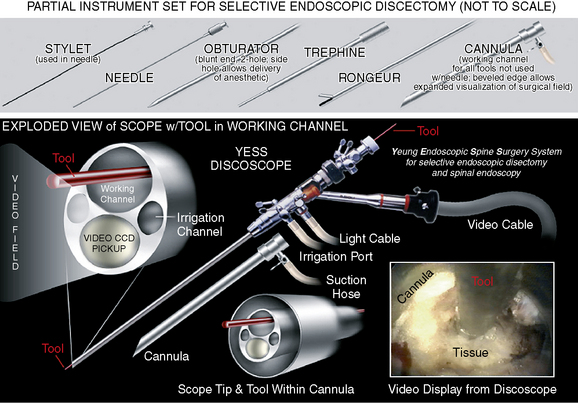

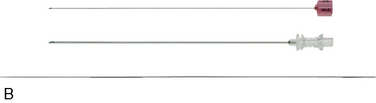

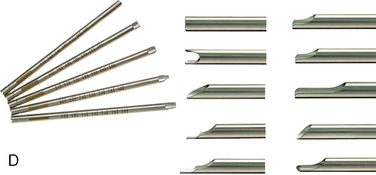

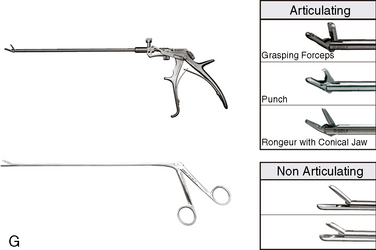

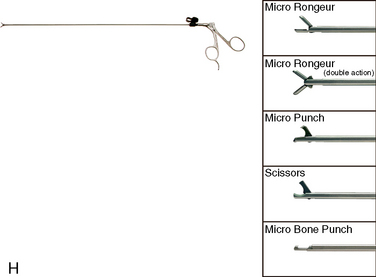

Necessary instrumentation and preparation for posterolateral endoscopic discectomy (Figs. 26-6 to 26-8) consists of the following:

Multichannel, 20-degree oval spinal endoscope with 2.7-mm working channel and integrated continuous irrigation (inflow and outflow) ports

Multichannel, 20-degree oval spinal endoscope with 2.7-mm working channel and integrated continuous irrigation (inflow and outflow) ports Flexible bipolar radiofrequency or laser probe for hemostasis, thermal contraction of the anular collagen, and thermal ablation of the anular nociceptors

Flexible bipolar radiofrequency or laser probe for hemostasis, thermal contraction of the anular collagen, and thermal ablation of the anular nociceptors Fluid pump for continuous irrigation, consisting of 2 mg epinephrine and 80 mL gentamicin per 1000 mL cold saline for the prevention of bleeding and infection

Fluid pump for continuous irrigation, consisting of 2 mg epinephrine and 80 mL gentamicin per 1000 mL cold saline for the prevention of bleeding and infectionProcedure

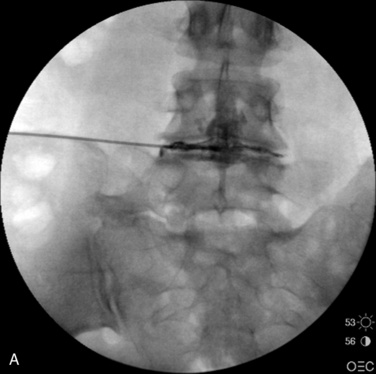

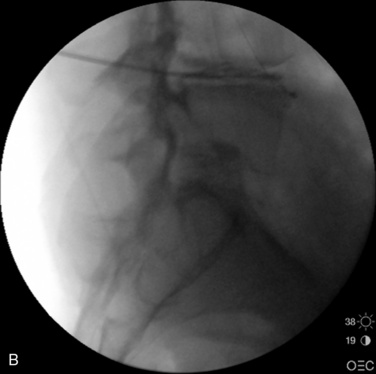

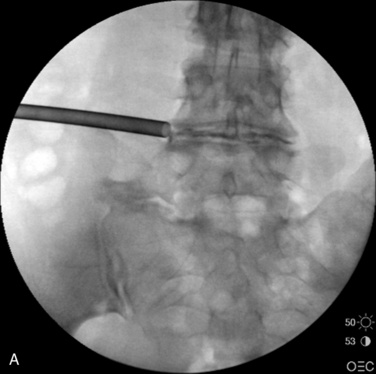

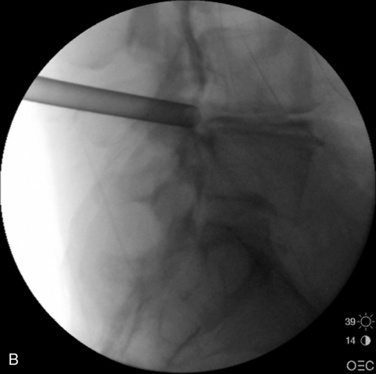

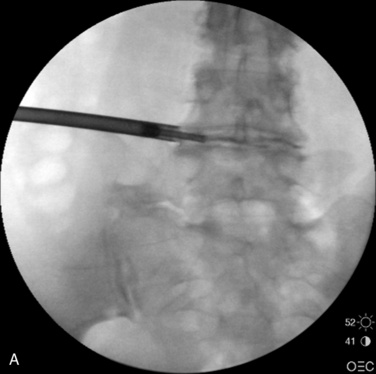

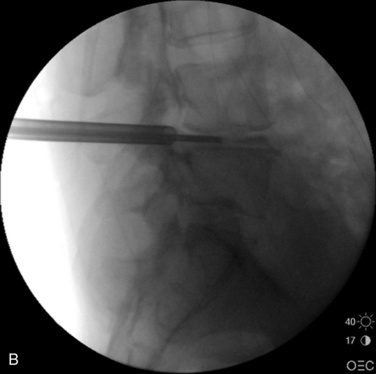

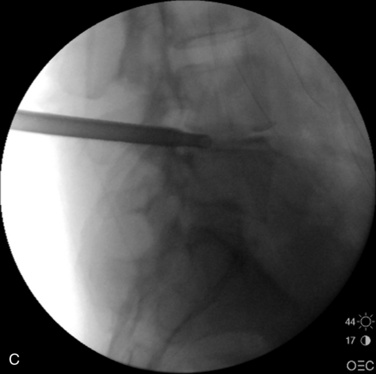

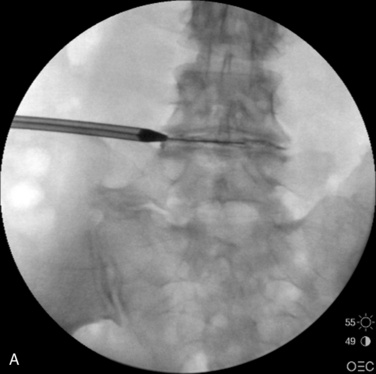

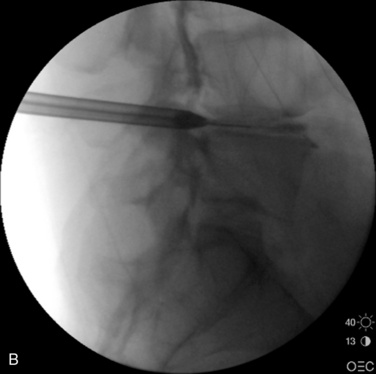

Figure 26–12 An obturator tube passes over the guidewire with confirmation on fluoroscopic AP (A) and lateral view (B).

Figure 26–16 Radiofrequency application for denervation of ingrown innervation and vascularization and for anuloplasty.

See also Table 26.3 and Figure 26-19 for a summary of the operative steps and Figures 26-20 and 26-21 for endoscopic views of the procedure.

Table 26.3 Steps of Percutaneous Selective Chromoendoscopic Nuclectomy

| Step | Chapter Figure(s) |

|---|---|

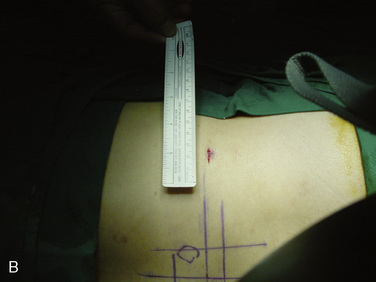

| Drawing for placement of needle and instrument | 26-9, 26-10 |

| Confirmatory chromodiscography and guidewire insertion | 26-11 |

| An obturator tube passes over the guidewire | 26-12 |

| Working sleeve inserted and obturator tube removed | 26-13 |

| Anulotome with small and large trephines | 26-14 |

| Endoscope placement through the sleeve | 26-15A |

| Selective nuclectomy | 26-15-B to F |

| Denervation and anuloplasty | 26-16, 26-17 |

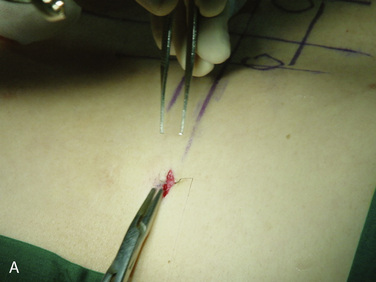

| Skin closure | 26-18 |

Postoperative care and follow-up

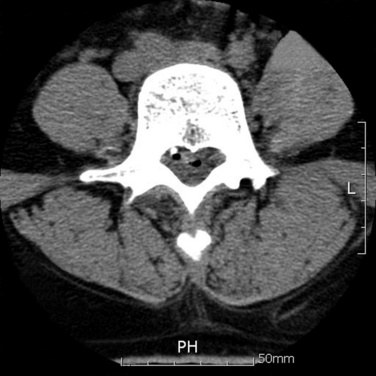

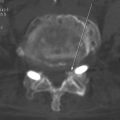

The straight-leg raising test result is improved immediately, and a postoperative nonenhanced computed tomography scan shows an air-filling shadow around the detached area (Fig. 26-22).

Caveats

For prevention of neural damage, the speed of advancement of the needle and obturator should be reduced.

For prevention of neural damage, the speed of advancement of the needle and obturator should be reduced. Before anulotomy, sufficient analgesia, such as local infiltration of the anulus with intravenous ketorolac or remifentanil, is needed.

Before anulotomy, sufficient analgesia, such as local infiltration of the anulus with intravenous ketorolac or remifentanil, is needed. To confirm sufficient disc decompression, the patient should be told to cough before decompression is considered finished.

To confirm sufficient disc decompression, the patient should be told to cough before decompression is considered finished.Selective posterolateral lumbar endoscopy was performed as described in the text of this chapter. During the discectomy, the patient felt relief of the radiating pain. Immediately after the procedure, tension signs had disappeared. The postoperative computed tomography scan demonstrated a decompressed extruded disc (see Fig. 26-22).