Selected Gynecologic Disorders

Ovarian Torsion

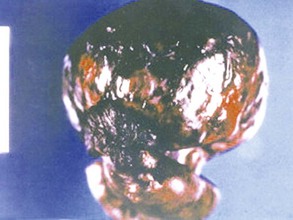

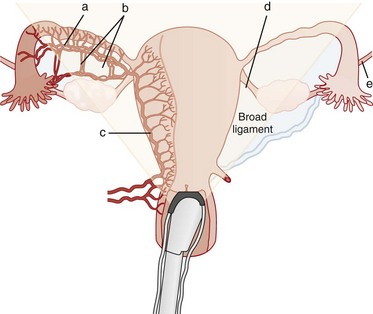

Ovarian torsion accounts for approximately 3% of gynecologic emergencies.1 While ovarian torsion can occur in young girls2 and is increasingly recognized in postmenopausal women, it is still most common in the reproductive years because of the regular development of a corpus luteal cyst during the menstrual cycle.3 Ovarian torsion is typically caused by a twisting of both the ovary and the fallopian tube on the vascular pedicle.4 Most cases of torsion (50-80%) are associated with an ovarian tumor, typically a benign neoplasm; with large, heavy cysts, as seen in ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome after in vitro fertilization; or with polycystic ovaries.1 Torsion may be a complication of pregnancy.5,6 Torsion of a normal ovary only rarely occurs.7 A slight predominance of ovarian torsion on the right side has been noted. The reason for this predilection is unclear but may relate to the stabilizing effect of the sigmoid colon on the left side.4 In ovarian torsion, venous and lymphatic obstruction occurs initially, with subsequent congestion and edema of the ovary, progressing to ischemia and necrosis and eventual infarction of the ovary1 (Fig. 100-1). Thrombosis of the ovarian vein and artery can occur as well. The ovary is often salvageable if the diagnosis is made before thrombosis occurs.4 Because of the dual blood supply of the ovary from both the uterine and ovarian arteries, complete arterial obstruction is rare7 (Fig. 100-2).

Clinical Features

Ovarian torsion can often be challenging to diagnose, because the classic symptoms of severe, sharp unilateral abdominal pain and nausea may not be present.5,6,8,9 The presence of known risk factors for ovarian torsion such as an ovarian mass or infertility treatments may suggest the diagnosis.1 Because the presentation can be variable and often subtle, the diagnosis can be difficult to make. In 87 patients with surgically confirmed torsion, the diagnosis was missed on the first visit in almost half of the patients. Patients reported pain from several hours to weeks in duration, most likely from intermittent ischemia, and almost all had some pain on abdominal palpation. Nausea was a symptom in many of the patients. Other series report similar findings.2–4,6,8

Diagnostic Strategies

No specific laboratory tests are helpful in the evaluation of a patient for suspected ovarian torsion, except for a pregnancy test to exclude ectopic pregnancy. A small percentage of patients may have an elevated white blood cell count above 15,000/µL,5 but this is not a reliable indicator of ovarian torsion.5,8

Imaging

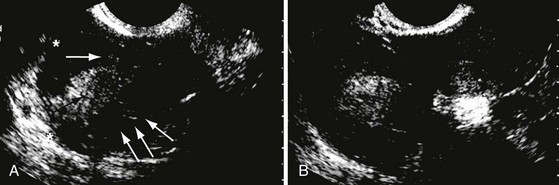

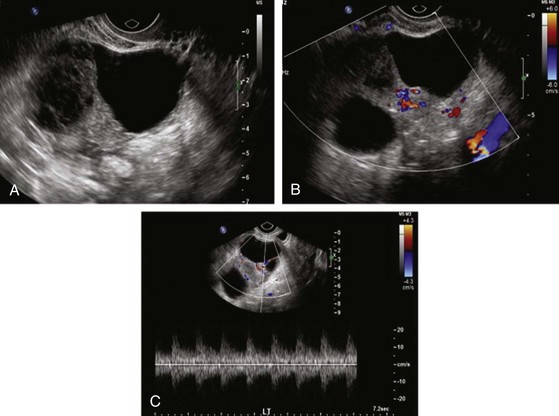

Ultrasonography.: Ultrasound examination is the initial imaging test in the evaluation of patients with pelvic pain suggestive of ovarian torsion.7 Enlargement of the ovary is the most common ultrasound finding,4 but the ovary also may have an abnormal position relative to the uterus. Enlargement of an ovary with a heterogeneous stroma and small, peripherally displaced follicles is the classic ultrasound appearance of torsion but is often absent, particularly early in the presentation4 (Fig. 100-3). The ultrasound study may reveal a mass in the ovary or evidence of hemorrhage10 (Fig. 100-4). The ultrasound appearance of ischemia can vary depending on the duration of the symptoms.11 Free pelvic fluid also may be seen.7 Hemorrhagic cysts and non-neoplastic masses frequently are associated with torsion. These may have a fluid-filled cystic component, exhibit a complex pattern with debris and septations, or be visualized as a solid mass.10 The characteristic appearance of torsion may be difficult to appreciate if the ovary is obscured by an associated mass.7

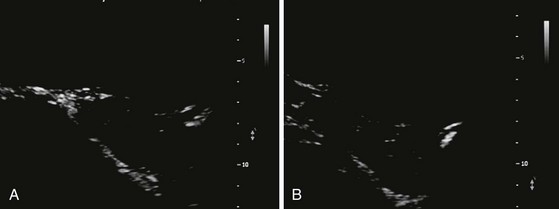

Doppler Ultrasound Examination.: Doppler ultrasound findings are inconsistent in ovarian torsion.7,12,13 Many cases of surgically proven torsion will have documented blood flow on Doppler examination because the ovary has a dual blood supply from both the ovarian and uterine arteries. Because the torsion may be intermittent, the findings may also vary depending on the time of the examination.7 If a large mass is present, the examination may be technically difficult to perform.9 Despite these limitations, the Doppler examination is still useful because detection of abnormal venous flow is particularly important in early cases of torsion10 (Fig. 100-5). Visualization of the twisting of the pedicle and the coiled vessels is referred to as a “whirlpool sign.”14,15 Lee and colleagues report an 88% accuracy for torsion when the twisted pedicle or whirlpool sign is visualized.16 In summary, the combination of ultrasound with Doppler studies is the initial study of choice in considering the diagnosis of ovarian torsion; however, it is important for the clinician to appreciate that many of the findings can be subtle and may be negative, particularly in early presentations.

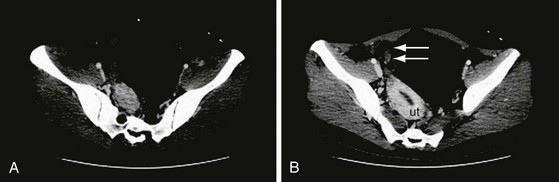

Computed Tomography.: When renal colic and appendicitis also are strong considerations in the differential diagnosis for acute pelvic pain, abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) may be the best initial study, particularly in patients who have a presentation atypical for torsion.17 In ovarian torsion, CT findings include fallopian tube thickening, smooth wall thickening of the associated adnexal mass, ascites, and uterine deviation to the twisted side18,19 (Fig. 100-6). Associated hemorrhage in patients with hemorrhagic infarction can be seen. A retrospective review of CT scans of patients with confirmed torsion found that every CT scan had evidence of an abnormality, including ovarian enlargement or the presence of a mass or cyst, suggesting that torsion is unlikely if the CT visualized a normal ovary.20 In contrast, another study of surgically confirmed ovarian torsion cases found that CT correctly diagnosed 5 of 13 cases (38%), as opposed to ultrasonography, which correctly identified 15 of 21 cases (71%).3 Therefore, negative imaging findings should be interpreted with caution when clinical suspicion is high, but with lower suspicion a normal-appearing ovary on CT scan can be reassuring.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging.: Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not typically ordered in the ED but may also demonstrate findings consistent with torsion. It is particularly helpful if the diagnosis is not clear, such as with intermittent pain over days, or when the history is highly suggestive but the ultrasound is not conclusive.21 Findings on MRI suggestive of torsion are similar to those on CT.18 Box 100-1 lists the common imaging findings in ovarian torsion.

Laparoscopy.: A diagnostic laparoscopy is the gold standard investigative modality in patients in whom clinical suspicion is high despite negative imaging results. In 100 nonpregnant patients with an acute abdomen, only 29 of the 66 laparoscopically proven cases of ovarian torsion were diagnosed preoperatively. Laparoscopy also allowed diagnosis of other unsuspected conditions, including ovarian cysts, appendicitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease.22

Management

Once the diagnosis of ovarian torsion has been made, the patient should be taken to the operating room as soon as possible. Pediatric patients taken to surgery more than 24 hours later have been found to have a zero salvage rate, compared with patients who had the best chance for salvage—those who were taken to the operating room within 8 hours.23 The ovary often will recover even if black in appearance at the time of surgery because of its dual blood supply, so attempts at ovarian salvage are warranted even if the diagnosis is made late.24 This is particularly true in adolescent patients. Ovarian function returns in a majority of patients with surgery that saves the ovary.23 Additional imaging studies, such as MRI, are an option if the diagnosis is not clear. Because torsion of a normal-appearing ovary is very rare, patients with a normal-appearing ovary on CT or ultrasound scan may be discharged from the ED.

Ovarian Cysts and Masses

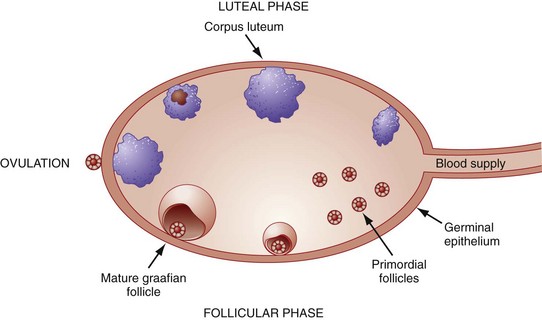

Ovarian cysts are the most common cause of gynecologic masses. They occur at any stage of life but are most frequent in the reproductive years because of the cyclic changes of the ovary associated with menstruation (Fig. 100-7). Most ovarian cysts are benign and resolve with no interventions, but on occasion they may be malignant or associated with significant complications such as hemorrhage or torsion.

Diagnostic Strategies

Imaging

Ultrasonography.: Ultrasonography is the standard initial imaging modality used to diagnose and characterize all ovarian pathologic processes and lesions including cysts and masses. Both transabdominal and endovaginal examinations provide useful information. The transabdominal approach permits an overall view of the pelvis and will visualize large masses and pelvic free fluid. Use of the endovaginal probe will provide a detailed picture of the ovary.10 Figures 100-8 and 100-9 present endovaginal views of a normal ovary, and Figure 100-10 illustrates a simple cyst. Follicular cysts are part of the normal architecture of the ovary, but a cyst is considered to be pathologic if it is larger than 2.5 cm in diameter. Depending on the timing of the scan and the degree of clot formation and lysis, hemorrhage may be seen as well. Ultrasound findings suggestive of malignancy include internal septations, solid elements, internal echoes, daughter cysts, thickened wall, and large amounts of ascites or free fluid.10

Computed Tomography.: When the differential diagnosis of unilateral pelvic pain is broad, particularly in the patient with associated gastrointestinal symptoms or more diffuse pain, a CT scan may be the initial imaging study. CT scan can also detect a cyst and associated complications including torsion as noted earlier. A follow-up ultrasound examination may be useful in select cases after the CT scan has been obtained, particularly if the cyst is complex. CT findings suggestive of malignancy are cystic-solid mass; necrosis in a solid lesion; cystic lesion with thick, irregular walls, papillary projections, or both; and the presence of ascites, peritoneal metastases, and lymphadenopathy.25

Management

Patients with a simple cyst and decrease in their symptoms may be safely discharged with referral for outpatient gynecologic follow-up to ensure resolution of the cyst. Most uncomplicated, simple cysts will resolve within a month. A recent prospective study followed premenopausal patients diagnosed with benign (<6 cm) cysts treated with conservative management for a median of 42 months.26 Lesions included simple cysts, hemorrhagic cysts, endometriomas, and hydrosalpinx. All the cysts resolved after 2 years, and no patients developed signs and symptoms of ovarian cancer. A complex cyst requires more urgent gynecologic intervention, and these patients may benefit from gynecology consultation in the ED, particularly if reliable follow-up is unlikely or if the patient is particularly symptomatic.

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding in the Nonpregnant Patient

An understanding of the normal menstrual cycle is invaluable in considering potential causes of abnormal uterine bleeding (Fig. 100-11). The menstrual cycle starts on the first day of menses. During the first part of the menstrual cycle, the endometrium thickens under the influence of estrogen, and a dominant follicle develops in the ovary, releasing an ovum at the midpoint of the cycle. After ovulation, the luteal phase begins and is characterized by production of progesterone from the corpus luteum. Progesterone matures the lining of the uterus, and if implantation does not occur, the corpus luteum dies, accompanied by sharp drops in progesterone and estrogen. These changes typically are followed by menstruation. Menstrual bleeding is usually predictable and cyclic and results from withdrawal of the effects of hormones on the endometrium, which occurs approximately 14 days after ovulation.

Figure 100-11 Normal menstrual cycle.

Disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis from a variety of causes can result in abnormal uterine bleeding. Returning the balance of estrogen and progesterone with oral contraceptives will help many patients regulate the cycle, with reduction in or cessation of abnormal uterine bleeding.26–30

Clinical Features

Abnormal uterine bleeding is a common presentation in the ED. A large number of possible conditions can cause abnormal uterine bleeding, and a systematic history and physical examination can help narrow the possibilities. Table 100-1 lists terms frequently used to describe abnormal uterine bleeding. (See Chapter 34 for further discussion.)

Table 100-1

| TERM | BLEEDING PATTERN |

| Menorrhagia | Bleeding occurring at regular intervals but with heavy flow (≥80 mL) or duration (≥7 days) |

| Intermenstrual bleeding | Irregular bleeding between cycles |

| Amenorrhea | Bleeding absent for 6 mo or more in a nonmenopausal woman |

| Midcycle spotting | Spotting occurring just before ovulation, typically from declining estrogen levels |

| Postmenopausal bleeding | Recurrence of bleeding in a menopausal woman at least 1 year after cessation of cycles |

| Acute emergent abnormal uterine bleeding | Bleeding characterized by significant blood loss that results in hypovolemic shock |

| Dysfunctional uterine bleeding | Ovulatory or anovulatory bleeding, diagnosed after the exclusion of pregnancy, medications, iatrogenic causes, genital tract pathology, and systemic disease |

Vaginal bleeding before the age of menarche is abnormal and is often the result of trauma, such as sexual abuse, or a structural lesion.31 In a woman of reproductive age, abnormal uterine bleeding includes a change in the duration, frequency, or amount of bleeding, or bleeding between menstrual cycles. In the postmenopausal woman, any bleeding 12 months after the cessation of menses or unpredictable bleeding during hormone therapy should be considered abnormal. The amount and frequency of bleeding and the duration of symptoms, as well as the relationship to the menstrual cycle, should be established.32 A menstrual cycle that is fewer than 21 days in duration or more than 35 days long or flow for less than 2 days or more than 7 days is classified as abnormal. A pattern of irregular bleeding between cycles or an abrupt change in the previous pattern of bleeding should be determined.33 Systemic disease, such as liver disease, diabetes, or thyroid disease, may be associated with abnormal uterine bleeding.34 Endometrial cancer is associated with underlying diabetes mellitus, anovulatory cycles, obesity, nulliparity, and age older than 35 years.29 Cervical dysplasia or other genital tract pathology may cause postcoital or irregular bleeding.35 Disruption along the hypothalamus-pituitary-ovarian pathway frequently is the cause of abnormal uterine bleeding. Causes of hypothalamic suppression include excessive exercise, stress, and weight loss.36 Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) results in excess estrogen production.

According to Dilley and colleagues, 10.7% of patients with heavy menstrual bleeding have an underlying coagulation disorder, most commonly von Willebrand’s disease.37 Although most patients with abnormal uterine bleeding do not require evaluation for coagulopathy, the diagnosis is suggested by a family history of a bleeding disorder, prolonged history of heavy menses, excessive bleeding with surgery or dental procedures, or easy bruising.38 Box 100-2 lists historical factors that suggest a potential cause for the bleeding.29 Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is a diagnosis of exclusion in a woman of childbearing age after pregnancy, malignancy, and systemic disease have been ruled out.29 Dysfunctional uterine bleeding typically is classified as anovulatory or ovulatory. Anovulatory bleeding is much more common, resulting from a disturbance of the normal hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, and is particularly common at the extremes of the reproductive years.28

Physical Examination

With prolonged, heavy bleeding, signs of chronic anemia may be noted on the physical examination. PCOS is a common cause of abnormal uterine bleeding. Physical findings suggestive of PCOS include obesity, acne, hirsutism, and acanthosis nigricans, which is hyperpigmentation typically seen in the folds of skin in the neck, groin, or axilla.39 Other causes of bleeding include vaginal or cervical lesions, which may be visible on the speculum examination. A leiomyoma or fibroid uterus may be palpable on the bimanual examination.40 Patients with endometrial cancer frequently have an enlarged uterus as well.

Diagnostic Strategies

In evaluating a woman of reproductive age with vaginal bleeding, a urine pregnancy test is the most essential laboratory test. In a patient with excessive bleeding, any hemodynamic instability, or clinical evidence of anemia (e.g., excessive fatigue, pale conjunctiva), a hemoglobin or hematocrit may be helpful. Coagulation studies should be considered in patients with underlying liver disease or other coagulopathies.38

Imaging

Ultrasonography.: Transvaginal ultrasonography may reveal a fibroid uterus, endometrial thickening, or a focal mass.41 Endometrium measuring less than 4 mm thick is under the influence of low estrogen—for example, either in the early follicular phase or in menopause. Thickened endometrium may indicate an underlying lesion or excess estrogen42 (Fig. 100-12). For a majority of nonpregnant patients with abnormal uterine bleeding, these ultrasound findings do not immediately affect ED decision-making. In patients who have access to adequate gynecologic services, imaging may be deferred until follow-up evaluation with the gynecologist. The decision to perform ultrasound imaging in the ED will depend on the urgency to determine the cause of bleeding and on the reliability of outpatient follow-up. ED pelvic ultrasound imaging in nonpregnant patients can determine the cause of the bleeding in approximately 60% of cases. Uterine fibroids are by far the most common diagnosis (Fig. 100-13), but in one study 9.6% of patients had endometrial changes suggestive of malignancy,43 illustrating the importance of arranging follow-up for any patient with new abnormal uterine bleeding.

Management

The likely causative disorder, as well as the amount of bleeding, will guide the ED management. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications are generally effective for relief of associated cramping pelvic pain.29 For anovulatory bleeding, combination oral contraceptive pills can help regulate the cycle and also counteract the effects of long-term effects of unopposed estrogen on the endometrium. In a patient who desires contraception and is not heavily bleeding on presentation to the ED, a combination oral contraceptive with 20 to 35 µg of ethinyl estradiol may be prescribed.28 In the patient with heavy bleeding, an oral contraceptive with 35 µg of estrogen can be taken twice a day for 5 to 7 days until the bleeding stops, at which time the dose is decreased to once a day until the pack is completed.29 This is often done by prescribing two packs of oral contraceptives and having the patient take one pill from each package until the bleeding stops then continue with one pill daily. Rarely, a patient will have uncontrolled bleeding and signs of significant blood loss on presentation. These patients should receive aggressive resuscitation with saline and blood as with other types of hemorrhagic shock. In these patients, surgical removal of the culprit lesion, if one is present, or an urgent dilation and curettage (D&C) procedure is likely necessary. Alternatively, intravenous conjugated estrogen (Premarin) may be used. The dose is 25 mg intravenously (IV) every 4 to 6 hours until the bleeding stops.44

Emergency Contraception

Emergency contraception, also commonly known as the morning-after pill, consists of therapy to prevent pregnancy after unprotected sexual intercourse. It is estimated that more than 1 million unintended pregnancies could be avoided per year if emergency contraception were used.45 The most common reasons cited by patients seeking emergency contraception include failure to use contraception and failure of the contraception method, such as a broken condom or missed oral contraceptive pill. A recent survey of 800 women of reproductive age found that only 6% of the women had ever used emergency contraception.46 Many women are not aware of the availability of this option, are not informed about its safety or use, or do not have access to the medications.46,47

Emergency contraception with high-dose estrogen was reported in the early 1960s and began to have widespread use after Yuzpe demonstrated the efficacy of a lower-dose combination of estrogen and progestin to prevent pregnancy in 1974.45,48,49 At present, levonorgestrel alone, marketed as Plan B in the United States, is more effective and has largely replaced the Yuzpe method.50 Nausea occurs in 18% of patients using Plan B and in 43% of women taking combination pills.51 Antiemetics given 1 hour before the combination pills are effective and should be considered with use of these pills. The incidence of nausea is much lower with Plan B, but antiemetics can be offered. The package insert of Plan B recommends taking the 0.75-mg pill as soon as possible and the subsequent dose 12 hours later; however, taking the doses simultaneously is equally effective. Emergency contraception should be administered before 24 hours if possible but can be given up to 120 hours after intercourse. The Yuzpe method is 87 to 90% effective if the regimen is given within 72 hours; this rate drops to 72 to 87% if the pills are given between 72 and 120 hours. Plan B is noted to be 89% effective in preventing pregnancy.45

Emergency contraception may be offered after inadequately protected intercourse to any woman who does not desire pregnancy. The typical contraindications to oral contraceptives do not apply to emergency contraception because the duration of therapy is so brief.52 Emergency contraception has no adverse effects on a developing fetus and does not pose a risk to an established pregnancy.53 A majority of nonpregnant women experience menses within a week of the expected time, but irregular bleeding may occur.37 It is still possible for a patient who uses emergency contraception to get pregnant in the same menstrual cycle, so she should be advised to use an alternative form of contraception and to undergo a pregnancy test if menstruation is delayed more than 3 weeks. Advance provision of emergency contraception does not increase the number of unprotected sexual encounters.54–57

In 2007, after FDA approval, Plan B became available nationally over the counter without a prescription. Pregnancy rates as well as rates of sexually transmitted diseases and sexual activity have remained unchanged even though the use of emergency contraception has increased.58 Even though Plan B is available over the counter, follow-up studies highlight ongoing barriers to access, including cost and patient awareness, and highlight the importance of continued education including education on the use of primary contraceptive methods.59–61

References

1. Oelsner, G, Shashar, D. Adnexal torsion. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;49:459.

2. Breech, LL, Hillard, PJ. Adnexal torsion in pediatric and adolescent girls. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;17:483.

3. Chiou, SY, Lev-Toaff, AS, Masuda, E, Feld, RI, Bergin, D. Adnexal torsion: New clinical and imaging observations by sonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1289.

4. Shadinger, LL, Andreotti, RF, Kurian, RL. Preoperative sonographic and clinical characteristics as predictors of ovarian torsion. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:7.

5. Houry, D, Abbott, JT. Ovarian torsion: A fifteen-year review. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;38:156.

6. Mazouni, C, Bretelle, F, Ménard, JP, Blanc, B, Gamerre, M. Diagnosis of adnexal torsion and predictive factors of adnexal necrosis. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2005;33:102.

7. Andreotti, RF, Shadinger, L, Fleischer, A. The sonographic diagnosis of ovarian torsion: Pearls and pitfalls. Ultrasound Clin. 2007;2:155.

8. Bouguizane, S, et al. Adnexal torsion: A report of 135 cases. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2003;32:535.

9. Huchon, C, Fauconnier, A. Adnexal torsion: A literature review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;150:8–12.

10. Lambert, MJ, Villa, M. Gynecologic ultrasound in emergency medicine. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2004;22:683.

11. Smorgick, N, Maymon, R, Mendelovic, S, Herman, A, Pansky, M. Torsion of normal adnexa in postmenarcheal women: Can ultrasound indicate an ischemic process? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;31:338–341.

12. Ben-Ami, M, Perlitz, Y, Haddad, S. The effectiveness of spectral and color Doppler in predicting ovarian torsion: A prospective study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;104:64.

13. Pena, JE, Ufberg, D, Cooney, N, Denis, AL. Usefulness of Doppler sonography in the diagnosis of ovarian torsion. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:1047.

14. Vijayaraghavan, SB. Sonographic whirlpool sign in ovarian torsion. J Ultrasound Med. 2004;23:1643.

15. Valsky, DV, Esh-Broder, E, Cohen, SM, Lipschuetz, M, Yagel, S. Added value of the gray-scale whirlpool sign in the diagnosis of adnexal torsion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36:630–634.

16. Lee, EJ, Kwon, HC, Joo, HJ, Suh, JH, Fleischer, AC. Diagnosis of ovarian torsion with color Doppler sonography: Depiction of twisted vascular pedicle. J Ultrasound Med. 1998;17:83.

17. Kalish, GM, Patel, MD, Gunn, ML, Dubinsky, TJ. Computed tomographic and magnetic resonance features of gynecologic abnormalities in women presenting with acute or chronic abdominal pain. Ultrasound Q. 2007;23:167–175.

18. Rha, SE, et al. CT and MR imaging features of adnexal torsion. Radiographics. 2002;22:283.

19. Hiller, N, et al. CT features of adnexal torsion. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:124–129.

20. Moore, C, Meyers, AB, Capotasto, J, Bokhari, J. Prevalence of abnormal CT findings in patients with proven ovarian torsion and a proposed triage schema. Emerg Radiol. 2009;16:115–120.

21. Haque, TL, Togashi, K, Kobayashi, H, Fujii, S, Konishi, J. Adnexal torsion: MR imaging findings of viable ovary. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1954.

22. Cohen, SB, et al. Accuracy of the preoperative diagnosis in 100 emergency laparoscopies performed due to acute abdomen in nonpregnant women. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8:92.

23. Anders, JF, Powell, EC. Urgency of evaluation and outcome of acute ovarian torsion in pediatric patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:532.

24. Oelsner, G, et al. Minimal surgery for the twisted ischaemic adnexa can preserve ovarian function. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2599.

25. Gatreh-Samani, F, Tarzamni, MK, Olad-Sahebmadarek, E, Dastranj, A, Afrough, A. Adnexal masses: Accuracy of detection and differentiation with multi-detector computed tomography. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;110:22–31.

26. Alcázar, JL, Castillo, G, Jurado, M, García, GL. Is expectant management of sonographically benign adnexal cysts an option in selected asymptomatic premenopausal women? Hum Reprod. 2005;20:3231–3242.

27. Pitkin, J. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. BMJ. 2007;334:1110.

28. Agarwal, N, Kriplani, A. Medical management of dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2001;75:199.

29. Albers, JR, Hull, SK, Wesley, RM. Abnormal uterine bleeding. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1915.

30. Daniels, R, McCuskey, C. Abnormal vaginal bleeding in the nonpregnant patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:751–772.

31. Hill, NC, Oppenheimer, LW, Morton, KE. The aetiology of vaginal bleeding in children: A 20-year review. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989;96:467.

32. Fraser, IS, Critchley, HO, Munro, MG. Abnormal uterine bleeding: Getting our terminology straight. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:591.

33. Livingstone, M, Fraser, IS. Mechanisms of abnormal uterine bleeding. Hum Reprod Update. 2002;8:60.

34. Krassas, GE. Thyroid disease and female reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:1063.

35. Rosenthal, AN, Panoskaltsis, T, Smith, T, Soutter, WP. The frequency of significant pathology in women attending a general gynaecological service for postcoital bleeding. BJOG. 2001;108:103.

36. Lazovic, G, Radivojevic, U, Milicevic, S, Milosevic, V, Spremovic, S. The most frequent hormone dysfunctions in juvenile bleeding. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 2007;52:35.

37. Dilley, A, et al. von Willebrand disease and other inherited bleeding disorders in women with diagnosed menorrhagia. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:630.

38. El-Hemaidi, I, Gharaibeh, A, Shehata, H. Menorrhagia and bleeding disorders. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:513.

39. Fraser, IS, Kovacs, G. Current recommendations for the diagnostic evaluation and follow-up of patients presenting with symptomatic polycystic ovary syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;18:813.

40. Lethaby, A, Vollenhoven, B. Fibroids (uterine myomatosis, leiomyomas). Clin Evid (Online). Jan 11, 2011.

41. Goldstein, SR, Zeltser, I, Horan, CK, Snyder, JR, Schwartz, LB. Ultrasonography-based triage for perimenopausal patients with abnormal uterine bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:102.

42. Tabor, A, Watt, HC, Wald, NJ. Endometrial thickness as a test for endometrial cancer in women with postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:663.

43. Stumpf, M, Tibbles, CD. Utility of pelvic ultrasound in non-pregnant patients with pelvic pain or vaginal bleeding. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:12.

44. DeVore, GR, Owens, O, Kase, N. Use of intravenous Premarin in the treatment of dysfunctional uterine bleeding—a double-blind randomized control study. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;59:285.

45. Ranney, ML, Gee, EM, Merchant, RC. Nonprescription availability of emergency contraception in the United States: Current status, controversies, and impact on emergency medicine practice. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:461.

46. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists, No. 69, December 2005 (replaces Practice Bulletin Number 25, March 2001). Emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1443.

47. Abbott, J, Feldhaus, KM, Houry, D, Lowenstein, SR. Emergency contraception: What do our patients know? Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:376.

48. Yuzpe, AA. Postcoital hormonal contraception: Uses, risks, and abuses. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1977;15:133.

49. Yuzpe, AA, Thurlow, HJ, Ramzy, I, Leyshon, JI. Post coital contraception: A pilot study. J Reprod Med. 1974;13:53.

50. Randomised controlled trial of levonorgestrel versus the Yuzpe regimen of combined oral contraceptives for emergency contraception. Task Force on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Lancet. 1998;352:428.

51. Raymond, EG, et al. Meclizine for prevention of nausea associated with use of emergency contraceptive pills: A randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:271.

52. Conard, LA, Gold, MA. Emergency contraceptive pills: A review of the recent literature. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;16:389.

53. Zhang, L, et al. Pregnancy outcome after levonorgestrel-only emergency contraception failure: A prospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:1605–1611.

54. Ellertson, C, et al. Emergency contraception: Randomized comparison of advance provision and information only. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:570.

55. Gold, MA, Wolford, JE, Smith, KA, Parker, AM. The effects of advance provision of emergency contraception on adolescent women’s sexual and contraceptive behaviors. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2004;17:87.

56. Jackson, RA, Schwarz, EB, Freedman, L, Darney, P. Advance supply of emergency contraception: Effect on use and usual contraception—a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:8.

57. Lo, SS, Fan, SY, Ho, PC, Glasier, AF. Effect of advanced provision of emergency contraception on women’s contraceptive behaviour: A randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2404.

58. Raine, TR, et al. Direct access to emergency contraception through pharmacies and effect on unintended pregnancy and STIs: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:54.

59. Maharaj, P, Rogan, M. Missing opportunities for preventing unwanted pregnancy: A qualitative study of emergency contraception. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2011;37:89–96.

60. Parrish, JW, Katz, AR, Grove, JS, Maddock, J, Myhre, S. Characteristics of women who sought emergency contraception at a university-based women’s health clinic. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201:22e1–7.

61. Goyal, M, Zhao, H, Mollen, C. Exploring emergency contraception knowledge, prescriptions, practices, and barriers to prescriptions for adolescents in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2009;123:765–770.