CHAPTER 22 Sedation for Percutaneous Procedures

INTRODUCTION

‘Sedation and analgesia’ describe a state in which patients can tolerate unpleasant procedures while maintaining cardiac and respiratory function and still maintain the ability to respond purposefully to both verbal commands and tactile stimulation. The Task Force on sedation and analgesia decided that the term ‘sedation and analgesia’ (sedation/analgesia) more accurately defines this therapeutic goal than does the commonly used but imprecise term ‘conscious sedation.’ This level of sedation does not include a level in which the only intact reflex is withdrawal from a painful stimulus.1 Although sedation has been described as ‘light sleep’2 and textbooks note that ‘the terms sleep, hypnosis, and unconsciousness are used interchangeably in anesthesia literature to refer to the state of drug-induced sleep,’3 pharmacological sedation is not the same as physiological sleep.

LEVELS OF SEDATION

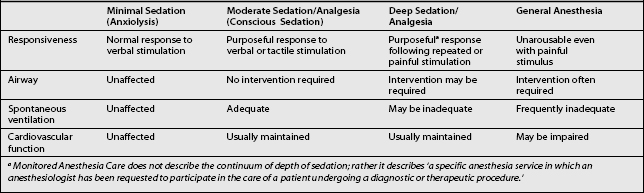

Deep sedation and general anesthesia are not usually recommended for most of pain management procedures, as an awake, cooperative patient is needed to prevent complications related to nerve injury, allergic reactions, or medication toxicity (Table 22.2).

| Clinical Score | Level of Sedation Achieved |

|---|---|

| 6 | Asleep, no response |

| 5 | Asleep, sluggish response to light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus |

| 4 | Asleep, but with brisk response to light glabellar tap or loud auditory stimulus |

| 3 | Sleepy, but responds to commands |

| 2 | Patient cooperative, oriented and tranquil |

| 1 | Patient anxious, agitated or restless |

GENERAL PREPARATION

Preprocedural assessment

All patients who are scheduled to receive sedation should be thoroughly evaluated prior to the procedure. Relevant issues that should be addressed include past medical history, past surgical history to include any anesthetic complications, drug allergies, and current medications to include anticoagulants, smoking, alcohol use and recreational drug history, and NPO status. The risk stratification classification of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) provides an excellent preprocedure assessment tool for this purpose (Table 22.3).

Table 22.3 American Society of Anesthesiologist Physical Class Risk Stratification

| Class I | Normal healthy patient |

| Class II | Mild systemic disease |

| Class III | Severe systemic disease |

| Class IV | Life-threatening illness |

| Class V | Moribund patient |

Table 22.4 provides a summary of the American Society of Anesthesiologists preprocedure fasting guidelines. The recommendations apply to healthy patients who are undergoing elective procedures. They are not intended for women in labor. Following the guidelines does not guarantee complete gastric emptying has occurred.

Table 22.4 Summary of American Society of Anesthesiologists Preprocedure Fasting Guidelines for Healthy Patients Who Are Undergoing Elective Procedures

| Ingested Material | Minimum Fasting Period |

|---|---|

| Clear liquids | 2 h |

| Nonhuman milk | 6 h |

| Light meal | 6 h |

The fasting periods noted in Table 22.4 apply to all ages.

Examples of clear liquids include water, fruit juices without pulp, carbonated beverages, clear tea, and black coffee.

Since nonhuman milk is similar to solids in gastric emptying time, the amount ingested must be considered when determining an appropriate fasting period.

A light meal typically consists of toast and clear liquids. Meals that include fried or fatty foods or meat may prolong gastric emptying time. Both the amount and types of foods ingested must be considered when determining an appropriate fasting period.

Airway assessment procedures for sedation and analgesia

The airway should be evaluated prior to giving sedative medications. Oversedation will cause respiratory depression and may require respiratory support. Oversedation can also cause aspiration, obstruction, bronchospasm, and laryngospasm requiring tracheal intubation and ventilatory support. Intubation may be especially difficult in patients with atypical airway anatomy. Airway abnormalities may also increase the likelihood of airway obstruction following the administration of sedatives and analgesics. Warning signs of a difficult airway are listed in Table 22.5. Recommendations for frequency of monitoring and documentation during sedation/analgesia are listed in Table 22.6.

| Previous problems with sedation |

| Stridor, snoring, or sleep apnea |

| Advanced rheumatoid arthritis |

| Chromosomal abnormality (e.g. trisomy 21) |

| Significant obesity (especially involving the neck and facial structures) |

| Short neck and limited neck extension |

| Decreased hyoid-mental distance (<3 cm in an adult) |

| Neck or anterior mediastinal mass |

| Cervical spine disease or trauma |

| Tracheal deviation |

| Dysmorphic facial features (e.g. Pierre–Robin syndrome) |

| Small opening (< 3 cm in an adult) |

| Edentulous |

| Protruding incisors |

| Loose or capped teeth |

| Dental appliances |

| High, arched palate |

| Macroglossia |

| Tonsillar hypertrophy |

| Nonvisible uvula |

| Micrognathia |

| Retrognathia |

| Trismus and significant malocclusion |

Table 22.6 Recommendations for Frequency of Monitoring and Documentation During Sedation/Analgesia1

| Monitoring | Conscious Sedation | Deep Sedation |

|---|---|---|

| Heart rate | Continuous | Continuous |

| Oxygen saturation | Continuous | Continuous |

| Respiratory rate | Minimum of every 15 min | Minimum of every 5 min |

| Noninvasive blood pressure | Minimum of every 15 min | Minimum of every 5 min |

| Level of consciousness | Minimum of every 5 min | Minimum of every 5 min |

EMERGENCY EQUIPMENT FOR SEDATION AND ANALGESIA

Appropriate emergency equipment should be available whenever sedative or analgesic drugs capable of causing cardiorespiratory depression are administered. Items in brackets are recommended when infants or children are sedated (Tables 22.7, 22.8).

| BASIC AIRWAY MANAGEMENT EQUIPMENT | |

| Compressed oxygen (tank with regulator or pipeline supply with flow meter) | |

| Ambu-bag | |

| Suction | |

| Suction catheters (pediatric suction catheters) | |

| Yankauer-type suction | |

| Face masks (various sizes) | |

| Oral and nasal airways (various sizes) | |

| Lubricant | |

| ADVANCED AIRWAY MANAGEMENT EQUIPMENT | (in addition to the above listed equipment) |

| For practitioners with intubation skills, laryngeal mask airways | |

| Rescue airways such as Combitube and esophageal obturatory airway | |

| Laryngoscope handles (tested) and laryngoscope blades | |

| Endotracheal tubes | |

| Cuffed # 6.0, 7.0, 7.5, 8.0 | |

| Uncuffed # 2.5, 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5, 6.0 | |

| Stylets | |

Table 22.8 Emergency Medications

| Amiodarone |

| Atropine |

| Diazepam |

| Diphenhydramine |

| Ephedrine |

| Epinephrine |

| Glucose (50%) (10% or 25% glucose) |

| Hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, or dexamethasone |

| Lidocaine |

| Midazolam |

| Nitroglycerin (tablets or sprays) |

| Vasopressin |

DRUG PRINCIPLES FOR SEDATION AND ANALGESIA

Common drugs for sedation

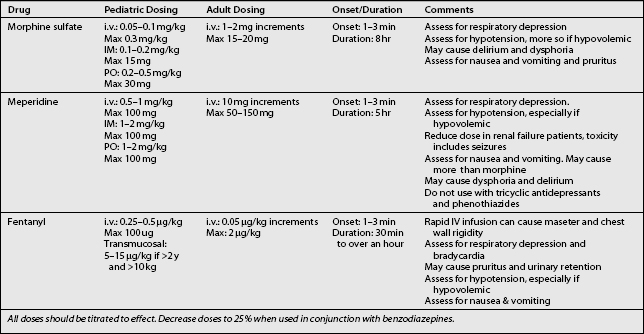

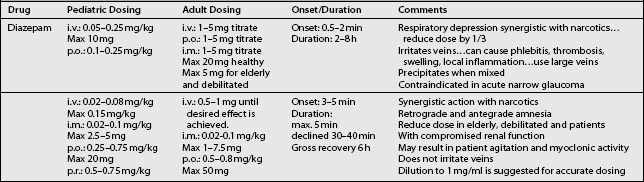

There is a variety of pharmacological agents commonly used for sedation/analgesia during interventional procedures. The most common reasons for using these agents are to promote anxiolysis, amnesia, analgesia, and sedation. Each of these agents have the potential to cause sedation and all can effect respiratory and cardiovascular function. The choice of the drug depends on whether the primary goal is anxiolysis, analgesia, or both. Generally, short-acting drugs are recommended for early recovery. In cases when polypharmacy is required, physicians must be aware of the synergistic and/or additive effects of these drugs. Sedating drugs should be administered slowly, with enough time for absorption. Only one drug should be administered at a time and the doses should be conservative. If necessary, a moderate dose of an additional drug may be added, but always infused slowly (Tables 22.9, 22.10).

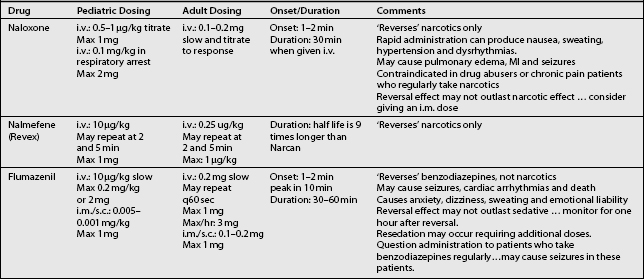

As previously mentioned, pharmacological antagonists or ‘reversal agents,’ such naloxone and flumazenil, must be readily available. Because these reversal drugs have their own side effects and complications, their routine use is discouraged. When used, the patients must remain for an extended duration to allow for monitoring of cardiovascular and respiratory depression, until the effects of the reversal agents dissipate (Table 22.11).

Because propofol, ketamine, pentothal, methohexial, and etomidate can easily and quickly result in general anesthesia for which no reversal agent is available, the authors recommend that these drugs should only be used by an anesthesia team.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

Recovery and discharge criteria following sedation and analgesia1

General principles

Guidelines for discharge

1 Gross JB, Bailey PL, Caplan RA, et al. Practice guidelines for Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologist. A report developed by the Task Force on Sedation and Analgesia by Non-Anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:459-471.

2 Lydic R, Baghdoyan HA, editors. Handbook of behavioral state control: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 1999.

3 Lydic R, Biebuyck JF. Sleep neurobiology; relevance for mechanistic studies of anesthesia. Br J Anesth. 1994;72:506-508.

4 Warner MA, Robert A. Caplan RA, Burton S, Epstein BS, et al. Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration: Application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures. A report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists. Developed by the Task Force on Preoperative Fasting and the Use of Pharmacologic Agents to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration.