Chapter 2 Securing the airway, ventilation and procedural sedation

SECURING THE AIRWAY

Differences between the airway anatomies of children and adults

Causes of airway obstruction and respiratory failure

Assessment and anticipation of airway obstruction

Factors confounding airway management

Cervical spine injury. Head and neck immobilisation must be maintained in the victim of blunt trauma until injury to the cervical spine is definitely excluded. If endotracheal intubation is indicated, it must be achieved without flexion, extension or distraction of the neck. Intubation should be performed while an assistant maintains in-line immobilisation, without traction, of the head and neck.

Manoeuvres to open or maintain the airway

Chin lift. Lift the jaw forward and support it with the mouth slightly open.

Manoeuvres to relieve foreign body obstruction

Finger sweep. To relieve obstruction in the oropharynx. Not recommended in infants.

Types of ventilation

Mouth-to-mask ventilation

Mask should incorporate a one-way valve. It is preferable to mouth-to-mouth ventilation.

Patients can be adequately ventilated until definitive assisted ventilation techniques are obtained.

Bag-valve-mask ventilation

Jackson Rees circuit is only suitable for use by an experienced resuscitator.

Endotracheal intubation

Technique of orotracheal intubation

Rapid sequence induction (RSI)

| Drug | Dose | Important effects |

|---|---|---|

| Induction agents | ||

| Thiopentone |

BP, blood pressure; HR, heart rate; K, potassium; ICP, intracranial pressure; IOP, intraocular pressure; PRN, as needed; RSI, rapid sequence induction

Suctioning

Yankauer sucker is used to remove secretions, blood, vomitus or foreign body from mouth and pharynx. In the unintubated patient, turn the patient on the side during suctioning.

Oxygenation and ventilation

Ventilator settings require decisions about minute ventilation, respiratory rate, inspired oxygen concentration, peak airway pressure and the use of positive end-expiratory pressure. (See the section ‘Choosing initial settings for ventilation’ in this chapter.)

A disconnection alarm must be used during mechanical ventilation.

Complications of intubation

Extubation

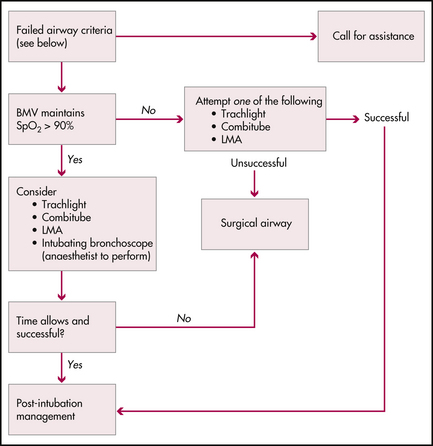

Alternative airway techniques

Laryngeal mask airway. Consists of airway with elliptical cuffed ‘mask’ on distal end which rests over the larynx when inserted. Low pressure ventilation may be performed, but it does not reliably prevent aspiration. Is quicker and an easier technique to learn than endotracheal intubation. Has an established role to provide an airway in the fasted patient during anaesthesia. Is a useful temporising technique if intubation skills are not available. When direct laryngoscopy and intubation fails it may serve to provide a functional airway until definitive intubation by cannulation of the trachea through the mask is performed.

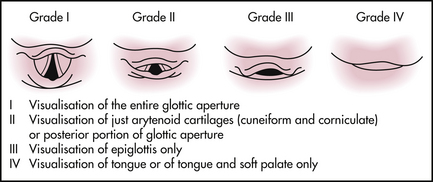

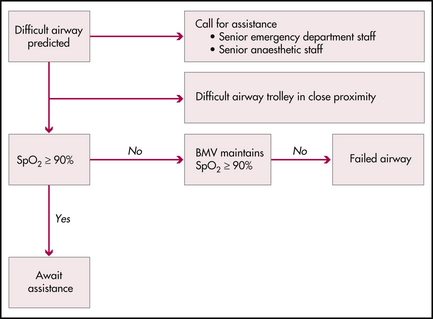

Guidelines for ‘difficult’ intubation

The difficult airway trolley

It is essential that all emergency departments have a difficult airway trolley. It should be well-organised and have clearly labelled contents. The exact contents of a difficult airway trolley may vary but should include a limited selection of tools to assist in securing the airway. The field of airway management is changing rapidly with new and, sometimes, improved devices becoming available. The trolley should reflect this. Its contents should be revised regularly and, if necessary, updated.

Securing the airway algorithms

VENTILATORS

Indications for ventilation fall into three broad categories:

Choosing initial settings for ventilation

Is the patient breathing spontaneously?

Spontaneously breathing patients are ventilated using a mode that assists each inspiratory effort by providing extra pressure or volume. Examples are continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and pressure support. Some ventilators and their circuits increase the work of breathing significantly and spontaneous breathing may not be tolerated. In these cases, the patient may need to be sedated and fully ventilated.

How much gas should the patient receive?

The minute volume is the amount of gas moved every minute:

Lung compliance is the change in lung volume for a given change in transpulmonary pressure. Diseased lungs often have abnormal compliance (e.g. in pulmonary oedema the lung is less compliant or ‘stiffer’). Trying to deliver a ‘normal’ tidal volume to a poorly compliant lung can cause high airway pressures, increasing the risk of pneumothorax. Overdistension can worsen lung damage. The approach to ventilating is usually one of providing limited tidal volumes (6–8 mL/kg, sometimes less) with PEEP. This can be done using either volume or pressure control.

Special situations

Adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS)

ARDS is a difficult problem. The ideal ventilatory strategy is controversial. In the emergency department the key points are: 1) to avoid barotrauma by using small tidal volumes and avoiding high airway pressures; 2) to use PEEP as tolerated and tolerate a high PaCO2. Paralysis may be necessary. Frequent adjustments to tidal volume and respiratory rate may be needed.

Troubleshooting

PROCEDURAL SEDATION

Requirements

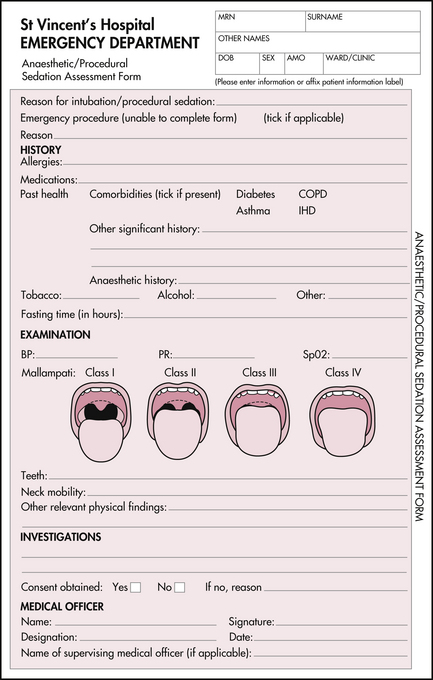

Procedural sedation should be undertaken in an area with working suction and oxygen. Pulse oximetry should be used. Continuous ECG and blood pressure monitoring may be used in selected patients (e.g. older or with cardiac history). Ready access to resuscitation equipment and emergency drugs is essential. At least one person should be present who has skills to manage any complications, including airway obstruction and cardiac arrest. All patients should have details recorded on a standard form. See Figure 2.4.

Fasting status does not necessarily preclude the use of sedation, but does influence the depth of sedation induced.

EDITOR’S COMMENT

In the management of an urgent airway problem, always have a prepared back-up plan in case the current manoeuvre is unsuccessful.

Bongard F.S., Sue D.Y. Current critical care diagnosis and treatment, 2nd edn. New York: Lange/McGraw-Hill; 2002.

Emergency life support manual. Emergency Life Support (ELS) Course Inc.

Finucane B.T., Santora A.H. Principles of airway management, 2nd edn. St Louis: Mosby; 1996.

Marx J.A., et al, editors. Rosen’s emergency medicine: concepts and clinical practice, 5th edn., St Louis: Mosby, 2001.

Padley A.P. Westmead pocket anaesthetic manual, 2nd edn. McGraw-Hill Australia; 2004.

Roberts J.R., Hedges J.R. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine, 4th edn. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2004.

Tintinalli J.E., Kelen G.D., Stapczynski J.S. Emergency medicine: a comprehensive study guide. American College of Emergency Physicians, 6th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003.

Walls R., et al, editors. Manual of emergency airway management, 2nd edn, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.