Chapter 12 Secondary Rhinoplasty

If one considers the number of factors that govern the outcome of rhinoplasty, the frequency with which suboptimal results mandate a secondary procedure is not surprising. Secondary rhinoplasty may be performed to eliminate minor imperfections (revision rhinoplasty) or may include many of the maneuvers routinely used during primary rhinoplasty (secondary rhinoplasty).

Summary

Introduction

Management of the secondary rhinoplasty patient is entirely different from the patient undergoing primary rhinoplasty, presenting a technical challenge and requiring even greater precision in planning and execution of the surgery. Skill is also required to manage the patient emotionally, analytically, and surgically, and to achieve aesthetic and functional objectives.1–5 Both comprehensive knowledge of potential problems and finesse during surgery are necessary to achieve the desired aesthetic goals. The surgeon must clearly understand the patient’s concerns; define the nasal imperfections, and establish realistic goals. In this chapter the manifold differences between primary and secondary rhinoplasties are explored and discussed, including patient evaluation, surgical planning, technical details, and postoperative management.

Patient Assessment and Definition of Nasal Flaws

Many patients seeking information about their first rhinoplasty are unaware of any breathing difficulties and often do not offer complaints of breathing problems. Careful observation often reveals that many of these patients are mouth breathers and internal examination may show significant airway compromise. The reason that these patients deny having breathing difficulty is that they have grown accustomed to obstruction and have no way of knowing how much better their breathing could be. Secondary rhinoplasty patients, on the other hand, are distinctly aware of breathing problems and commonly associate it with previous surgery. These patients have a baseline for airflow with which the change in the airway that occurred after the previous rhinoplasty can be compared. They are keenly aware if functional capacity is not what it used to be. The patient’s airway may have been adversely affected as a consequence of an alteration in internal or external valve function,6,7 formation of scar tissue, medialization of the inferior turbinates and upper lateral cartilages, or any combination thereof.8

Careful assessment of the face may disclose other facial disharmonies relevant to the rhinoplasty that may be contributing to the patient’s dissatisfaction. These abnormalities may include forehead prominence or retrusion, variations of chin deformities,9,10 hypoplasia of the malar bones, and a dysmorphic maxilla or mandible. If these disharmonies go undetected, achieving an optimal outcome is difficult, if not impossible. These features, only if deemed detrimental to the outcome of rhinoplasty, should be brought to the patient’s attention and documented. However, insistence in correcting these flaws as a condition to proceeding with the rhinoplasty should be avoided. It is crucial to ensure that the patient has realistic goals and expectations, and is not suffering from a psychological condition that may result in patient dissatisfaction in spite of a successful technical outcome. Disproportionate concern about the nose form should be analyzed carefully since the incidence of body dysmorphic disorder is higher on this group of patients, as outlined in the primary rhinoplasty chapter. Additionally, recommendations for selection of patients, also profiled previously, should be carefully considered.

Physical Examination

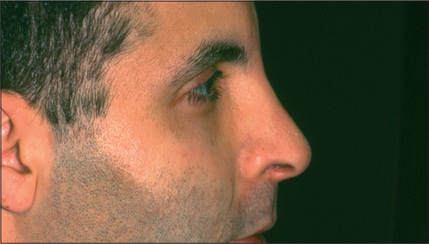

A systematic examination of the external nose starting from the radix and ending at the subnasale, may disclose a variety of imperfections. An under-resected radix, which is a fairly common finding, results in an undesirable transition from the forehead to the nose and is commonly associated with an appropriately lowered dorsum but a fuller than ideal radix (Fig. 12.1). The radix may also be too deep as a result of a preexisting problem that was not corrected or perhaps of under-correction during the initial surgery. Over-reduction of the radix is extremely rare.

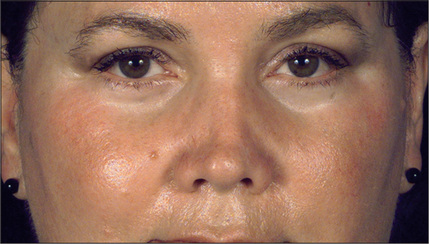

Asymmetry or irregularity of the nasal bones is another common cause of concern for the secondary rhinoplasty patient (Fig. 12.2). In an optimal rhinoplasty outcome, there is a graceful transition of shadows from the eyebrows to the tip of the nose. With suboptimal results, these dorsal defining lines are distorted or a second line posterior to the existing dorsal line can be seen, usually indicating a step deformity due to the nasal bone osteotomy being too anterior (Fig. 12.3). Upper lateral cartilages may also appear asymmetric as a result of unilateral over-resection or, more commonly, caused by anterior deviation of the septum (Fig. 12.4). Over-resection at mid-vault may result in an inverted V deformity as a consequence of collapse and medial shifting of the upper lateral cartilage (Fig. 12.5). Increased awareness of this problem and, especially, the use of spreader grafts, have reduced the prevalence of this deformity, although it is still seen fairly commonly. This imperfection is often not noticeable intraoperatively, early postoperatively, or even after up to 1-2 years after surgery. Depending on the thickness of the skin, it may only become discernible several years after surgery.

Fig. 12.4 Deviation of anterior septum resulting in appearance of asymmetric upper lateral cartilages.

Abnormalities in the tip area may range from minor imperfections, such as asymmetry of the domes, to gross deformities and complete distortion.11 An under-projected tip is a common feature of noses requiring secondary surgery. Nasal-tip width abnormalities are also prevalent. The alar rims may be retracted or hanging. Disproportionate width of the alar base is a common undesirable finding in noses as well. Supratip deformity may develop as a consequence of inadequate resection of the caudal aspect of the dorsum, but it is more commonly the result of excessive dorsal resection, loss of tip projection during healing, or a combination of factors.12 As stated previously, overresection of the caudal dorsum may result in scar formation and contraction, which ultimately create fullness in the supratip area (Fig. 12.6).

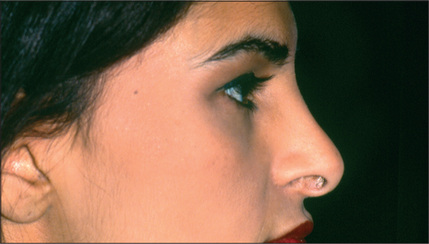

An obtuse nasolabial angle (over-shortened nose) was the hallmark of rhinoplasties performed during the 1970s and early 1980s. Suboptimal tip rotation is fairly common today due to repeated pleas for conservatism by rhinoplasty educators. The columella may appear too caudal in relation to the alar rim in many of the secondary rhinoplasty candidates as a result of alar retraction, protrusion of the caudal septum (Fig. 12.7) or, more commonly, due to placement of a columella strut. The ideal amount of columella visible on lateral view is between 2 mm and 3 mm. Excessive columellar show is displeasing and requires correction. Conversely, the columella may ostensibly appear retracted as a result of excess caudal extension of the alar rim or could be truly retracted as a consequence of a short anterior septum.

The nasal valves should be observed during inspiration. Collapse of the nasal valves was a common sequelae of the rhinoplasties per-formed before 1980, when many noses underwent aggressive resection of the midvault. This problem, although still existent, is less common today. Intranasal examination may also reveal inadequate correction of the preexisting septal deviation, septal perforation, enlarged inferior turbinates, synechiae, or neglected polyps.6,7

Because of the variety of nasal imperfections possible in patients undergoing secondary rhinoplasty and the precision required to define and correct these deformities, patient assessment using digital life-sized photographs becomes even more critical than in planning a primary rhinoplasty.13 Life-sized photographs provide a blueprint for surgery and ensure synchronicity between the surgeon’s and patient’s goals.

Surgical Techniques

Incision

Minor revisions can be performed using an endonasal approach. However, an exonasal approach through a columellar step incision is preferred for major revisions or a full secondary operation.14,15 This approach affords the surgeon a better exposure and opportunity for identification of the anatomy and pathologic conditions. If the patient’s initial surgery or previous revisions were performed using an open technique, a slight delay phenomenon will have occurred, providing more safety for the second operation with respect to the soft tissue circulation. If an endonasal approach has been used previously, the secondary procedure can still be performed successfully using an open technique.

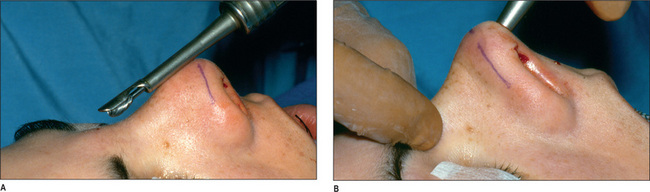

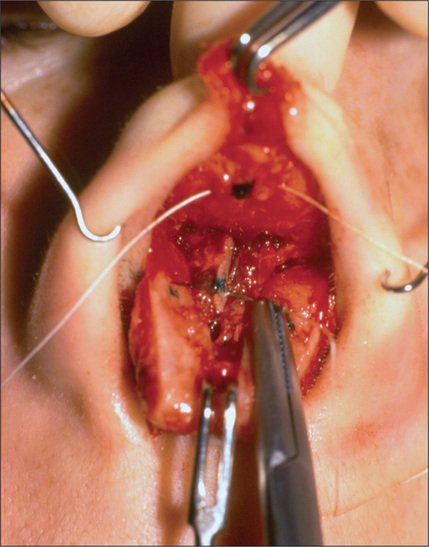

Alteration of the radix

An under-corrected radix can be rectified by removal of bone from this area using a guarded burr.16 This tool is safe and extremely effective if used properly. After the skin and soft tissue in the nasion area have been adequately elevated, the guarded burr is introduced into the site (Fig. 12.8). The surgeon can lower the nasion in an incremental fashion by gently moving the rotating burr from side to side. If the dorsal hump is large, removing it first may facilitate insertion of the guarded burr between the skin and the bone of the radix. Occasional soft tissue interference with the movement of the burr should not discourage its use. Repeated, judicious use of this tool will achieve the intended objectives. However, caution should be exercised because this tool is very powerful and may result in excessive bone removal if used too zealously.

Correcting the dorsal deficiency

A depression resulting from over-resection or asymmetric resection of the midvault is a common finding during secondary rhinoplasty. This will often require a cartilage graft. Septal cartilage is the preferred graft source to rectify an over-resected dorsum. If the patient has undergone septoplasty previously, the available septal cartilage may be insufficient. However, the mere history of septoplasty should not cause the surgeon to avoid exploring the septum. If available, the septal cartilage graft is prepared and gently crushed, and the margins are beveled to prevent a harsh dorsal line or step (Fig. 12.9). The graft is sutured to the dorsum to avoid shifting. It is important to dissect the soft tissues adequately to avoid forcing the graft out of desired position while healing. The caudal portion of the graft should be narrower than the central portion (fusiform).

Harvesting costal cartilage graft

If the costal cartilage is used to avoid warping the cartilage, the surgeon must follow Gibson’s principles17 or place a permanent Kirschner wire in the center of the cartilage to avoid warping.18 If an osteotomy is necessary to correct asymmetry or excess width of the nasal bones, it is crucial that the surgeon perform the osteotomy first, and then apply the dorsal cartilage graft.

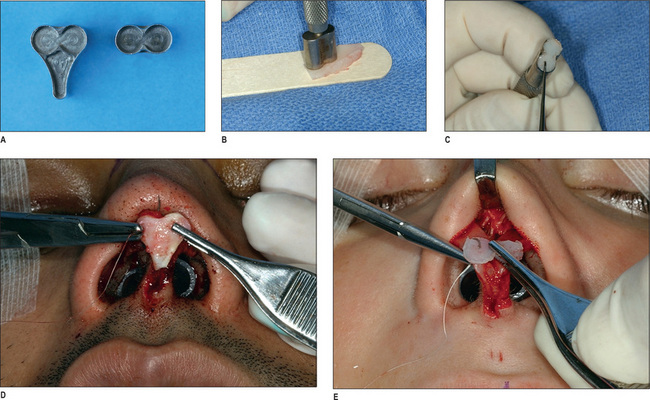

Correction of inverted V-deformity and nasal collapse

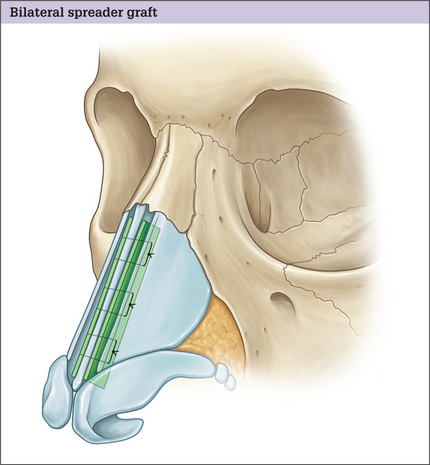

It is commonly necessary to restore the competency of the internal valves on secondary rhinoplasty patients by repositioning the upper lateral cartilages. Collapse of the upper lateral cartilages disturbs the function of the nose and engenders an undesirable nasal form known as an inverted V deformity, as referred to earlier.4 Less severe deformities can be corrected by using a spreader graft;4 more significant deformities require the use of a splay graft.19

To insert the spreader graft, the upper lateral cartilages and muco-perichondrium are separated from the septum. An appropriately sized graft extending from the junction of the nasal bone and the upper lateral cartilages (Keystone area) to the caudal end of the upper lateral cartilage is prepared. This graft is designed approximately 3 mm wide and 12-15 mm long; its thickness varies depending on the degree of the internal valve collapse (Fig. 12.10). If the graft is too thin to achieve the intended result, two layers are used. The graft is fixed in position using at least two through-and-through 5-0 monocryl mattress sutures. This step is crucial; otherwise, the graft may become dislodged while the splint is being applied, or during healing, which will result in a loss of function and may induce a discernible dorsal irregularity. The upper lateral cartilages are then sutured to spreader grafts and the septum. Placement of the spreader grafts may have more of a positive effect on the creation of optimal dorsal outline than the valve function.

Fig. 12.10 Artistic illustration of bilateral spreader graft in position and fixed with three sutures.

The splay graft is employed when the lower lateral cartilages are too attenuated or too short to allow a spreader graft to provide sufficient improvement in the valve function and achieve the intended aesthetic goals. The graft is tailored to extend from the posterior extent of one upper lateral cartilage to the opposite side, spanning the anterior septum.19 When the graft is inserted, the splay effect provides significant and enduring competency to the internal nasal valves. The open technique, again, is the preferred approach for the placement of this graft. The mucoperichondrium is separated from the medial aspect of the upper lateral cartilages bilaterally to create a pocket that extends to the posterior limits of the upper lateral cartilage. Preferably, a conchal cartilage graft is harvested, tailored, placed in position, and fixed to the underlying anterior septal border, using 5-0 PDS suture. It may be necessary to minimally bruise the septal cartilage to avoid excessive widening of the lower portion of the nose. After the cartilage is fixed to the septum, the anterior border of the upper lateral cartilages is sewn to the cartilage graft under mild tension to create continuity, strength, and proper contour. If the dorsal projection is considered to be optimal before application of the splay graft, it is necessary to lower the existing dorsal contour commensurate with the thickness of the cartilage graft to avoid excessive projection of the dorsum.

Adjustment of the caudal dorsum

The caudal dorsum may appear over-projected as a result of inadequate resection, causing a supratip deformity, which can be easily contoured. After the dorsum is exposed, the upper lateral cartilages are dissected and separated from the antero-caudal septum. It is essential to maintain the mucoperichondrium over the caudal nasal vault intact to prevent collapse of the upper lateral cartilages. These tissues at the antero-caudal area are somewhat rigid after a primary rhinoplasty. On rare occasions this rigidity of the soft tissues after removal of the anterocaudal septum is enough to prevent skin from draping over the newly shaped dorsum and may produce a space, setting the stage for a recurrent supratip deformity. Use of a supra-tip suture will reposition the soft tissue tenting over the caudal septum and will eliminate this dead space (Fig. 12.11). Commonly, the supratip deformity can be the consequence of an over-resected caudal dorsum or the result of leaving a dead space that fills with clotted blood, subsequently becoming scar tissue. When this occurs, the scar tissue is removed, a cartilage graft is applied to the caudal dorsum and supra-tip suture is used.

Tip refinement

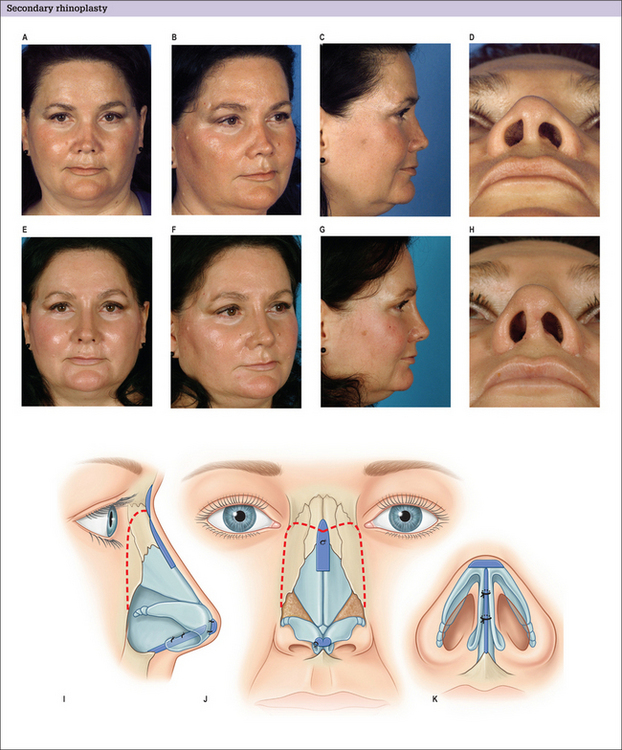

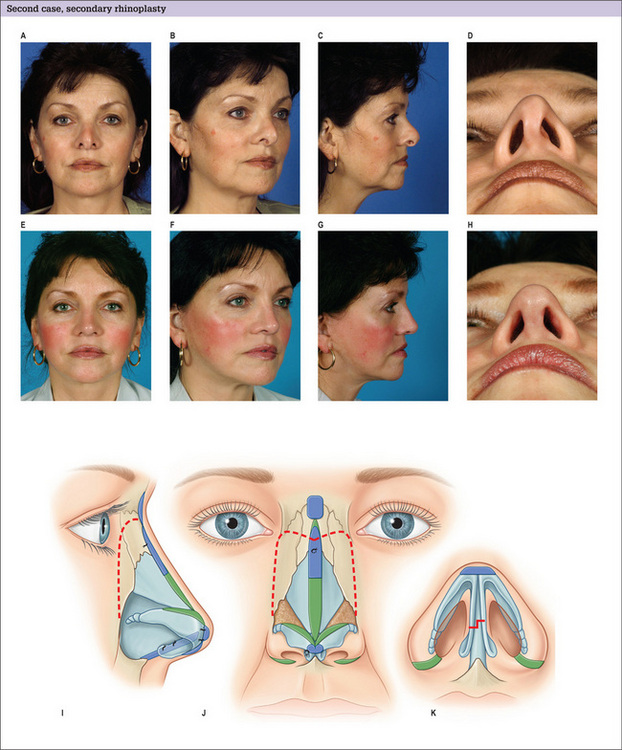

Secondary nasal tip deformity is exceedingly prevalent. The pathology can include over-projection, under-projection, excessive or inadequate width, or asymmetry. All of the principles discussed in the previous chapter apply here as well. Excess width can be controlled with suture technique. If the domal arches are too wide, a transdomal (dome defining suture) would be used. If the domes have proper shape but are positioned further apart, an interdomal suture would be a better choice. Commonly, the continuity of the domes and upper lateral cartilages has been interrupted, rendering the suture technique difficult, if not impossible. Furthermore, the cartilages are more rigid. These factors set the stage for an unpredictable response and asymmetry; thus, more intra-operative trials are necessary for the placement of the sutures than for the primary tip adjustments. Under these conditions, a subdomal graft would control the interdomal distances and a tip graft would restore a better form to the nose.20 Inadequate tip projection can be improved with the suture technique, application of a columellar strut, placement of a tip graft, or a combination of the methods. If the projection deficiency is minimal and the domal arches are too wide, placement of a transdermal suture will achieve both goals. It will narrow the domes and increase projection. If the inadequate tip projection is because of a short columella, a columellar strut is used. If the problem is the deficiency in the lobule, a tip graft will be utilized as an onlay or a shuttle graft (Fig. 12.12). The excess projection can be lessened either by resecting the footplates and the lateral crura using the tripod concept, depending on the nose length and projection, or by removing the domes if they are too wide or distorted to be avoided by using less invasive maneuvers.

Lateral crura strut

A lower lateral strut can correct the collapse of lower lateral cartilage.18 The lower lateral strut is a piece of cartilage placed under the surface of the existing lower lateral cartilage, extending from the maxilla to the ipsilateral dome.

Correction of protruding columella

Excess caudal projection of the columella can be corrected by resecting a rectangle-shaped piece of cartilage from the caudal septum and a commensurate amount of lining from the membranes of the septum. If an anteriorly based, triangle-shaped cartilage is resected, it will induce cephalic rotation of the nasal tip. If the nose is under-projected and the patient exhibits excessive caudal projection of the columella, the footplates and the medial crura can be overlapped and fixed over the caudal septum.21 This is called the Fred technique.

Tip graft

For patients with a deficient lobule and inadequate tip protection, an onlay or shield type tip graft is the preferred approach. Nasal elongation for correction of an over-shortened nose can be accomplished by adding a cartilage graft to the caudal septum or by placing a strut that extends from the medial crura to the septum, advancing the columella caudally. This strut also may advance the alar rim, as long as the medial crura and domes, and the lateral crura are still in continuity, and the cephalic scar tissue has been released sufficiently. If the alar rims are in an optimal position, an onlay lobule cartilage graft may advance the columella effectively without altering the alar rims. However, this is only applicable when there is minimal deficiency.22 The tongue and groove technique can be used to elongate the short nose of varying degrees.

Footplates

The footplates may be widely displayed or coould be asymmetric. This disharmony is corrected through the posterior portion of the hemitransfixion incision. In the case of an under-projected tip and splayed footplates it is advisable to approximate the footplates, which will strengthen the tip support and narrow the base of the columella. For the short nose, the footplates are resected and the medial crura approximated, resulting in caudal rotation of the tip.

Correction of retracted alar rim

If the retraction is minimal, it can be corrected with placement of analar rim graft.23 A piece of septal, conchal, or even costal graft is crafted3 mm wide, 1 mm or less thick, and 8-10 mm long. A pocket is createdalong the alar rim through an anterior incision. The graft is placed inposition and sutured using 6-0 absorbable catgut.

Alar base abnormalities

Most secondary rhinoplasty patients have a wider alar base than optimal with some degree of asymmetry. Alar base reduction6 can be performed by removing tissue from the nostril sill, the lateral alar base, or a combination of both as dictated by the alar dysmorphology. What is important, however, is that the graceful transition from the alar base to the nostril sill should not be compromised because of a fear of scarring. As the alar base advances medially, the alar rim will relocate caudally to some degree. The alar base incisional scars usually heal favorably unless the patient has thick sebaceous skin or has already demonstrated poor healing potential in the previous surgery. Many patients benefit from a combination of several of the aforementioned techniques (Figs 12.12, 12.13 & 12.14).

Splint and packing

In most patients, minor revision rhinoplasty can be performed with predictable or satisfactory outcome, and patient and surgeon satisfaction. It is the major secondary rhinoplasty that can be somewhat unpredictable and may require additional revision in a small percentage of patients. It is the combination of presence of scar tissue, lack of appropriate sources for a graft (as a result of previous septoplasty or use of grafts), a change in the vascularity of the tissue, and a shortage of lining that makes the results of secondary rhinoplasty less predictable than the primary rhinoplasty.

Pitfalls

1. Juri J., Juri C. Secondary rhinoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 1987;18:366-376.

2. Millard D.R. Secondary corrective rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1969;44:545-557.

3. Peck G.C. Secondary rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1988;15:29-41.

4. Sheen J.H. Secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;56:137-145.

5. Szalay L. Early secondary corrections after septorhinoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1996;20:429-432.

6. Constantian M. The incompetent external nasal valve: pathophysiology and treatment in primary and secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:919-931.

7. Constantian M., Clardy R.B. The relative importance of septal and nasal valvular surgery in correcting airway obstruction in primary and secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;98:38-54.

8. Guyuron B. Nasal osteotomy and narrowing of the airway, Presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons, San Francisco, 1997. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998.

9. Guyuron B. Genioplasty. Boston: Little, Brown & Co, 1992.

10. Guyuron B., Michelow B., Willis L. Practical classification of chin deformities. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1995;19:257-264.

11. Nicolle F. Secondary rhinoplasty of the nasal tip and columella. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;20:489-499.

12. Guyuron B., DeLuca L., Lash R. Supratip deformity: a closer look. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:1140-1151.

13. Guyuron B. Precision rhinoplasty. I. Role of life-size photographs and soft tissue cephalometric analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988;81:489-499.

14. Daniel R. Secondary rhinoplasty following open rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:1539-1546.

15. Gunter J.P., Rohrich R. External approach for secondary rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;80:161-174.

16. Guyuron B. Guarded burr for nasofrontal deepening. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;84:513.

17. Gibson T., Davis W.B. The distortion of autogenous cartilage grafts: its causes and prevention. Br J Plast Surg. 1958;10:257.

18. Gunter J.P., Friedman R.M. Lateral crural strut graft: technique and clinical applications in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99:943-952.

19. Guyuron B., Englebardt C.L. The alar splay graft. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons. 1997. New York, May 5

20. Guyuron B., Poggi J.T., Michelow B.J. The subdomal graft. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:1037-1040.

21. Fred G.B. The nasal tip in rhinoplasty: use of the invaginating technique to prevent secondary drooping. Ann Otolaryngol. 1950;59:215-223.

22. Hamra S.T. Lengthening the foreshortened nose. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:547.

23. Guyuron B. Alar rim deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:856-863.