Chapter 38 SCROTAL MASSES

General Discussion

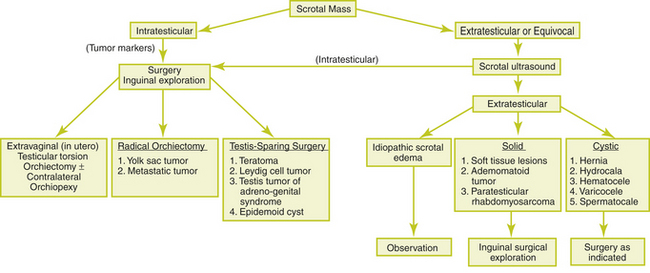

The most common painless scrotal masses in infants, children, and adolescents include indirect inguinal hernias, hydroceles, varicoceles, and spermatoceles. Testicular tumors, perinatal testicular torsion, acute idiopathic scrotal edema, and soft tissue tumors of the spermatic cord are less common causes. Figure 38-1 provides a clinical approach to the painless scrotal mass.

Painless Intratesticular Masses

Gonadoblastoma is a rare tumor that occurs in patients with intersex and dysgenetic gonads.

Causes of Scrotal Masses

Key Physical Findings

Careful palpation and identification of the intrascrotal contents

Careful palpation and identification of the intrascrotal contents

Testicular examination for volume, masses, or tenderness

Testicular examination for volume, masses, or tenderness

Evaluation of the contralateral testis for bilateral testicular lesions

Evaluation of the contralateral testis for bilateral testicular lesions

Transillumination of the testicular mass

Transillumination of the testicular mass

Assessment of the spermatic cord

Assessment of the spermatic cord

Examination of the inguinal canals for a hernia or cord tenderness

Examination of the inguinal canals for a hernia or cord tenderness

Valsalva maneuver to evaluate for hernia or varicocele

Valsalva maneuver to evaluate for hernia or varicocele

Abdominal examination for masses

Abdominal examination for masses

Suggested Work-Up

| Scrotal ultrasound | To help define suspected lesions and differentiate between intratesticular and extratesticular lesions |

Additional Work-Up

| Serum | Elevated in more than 80% of patients with yolk sac testicular tumors. It is not elevated in pediatric patients with testicular teratomas. Normal serum levels of AFP remain elevated for the first 8 months after birth. |

| Serial follow-up and serum AFP | If testicular microlithiasis is seen in association with testicular enlargement |

| Chest radiography and CT scan of the abdomen and chest | Indicated if the diagnosis of a yolk sac tumor is made |

| Serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) | Little or no value in pediatric patients |

1. Haynes J.H. Inguinal and scrotal disorders. Surg Clin North Am. 2006;86:371–381.

2. Jayanthi V.R. Adolescent urology. Adolesc Med Clin. 2004;15:521–534.

3. Junnila J., Lassen P. Testicular masses. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57:685–692.

4. Skoog S.J. Benign and malignant pediatric scrotal masses. Pediatr Clin of North Am. 1997;44:1229–1250.