Screening the newborn for disease

Neonatal screening programmes

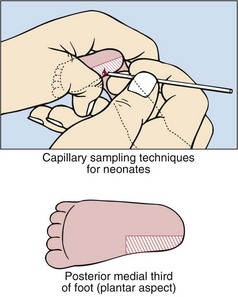

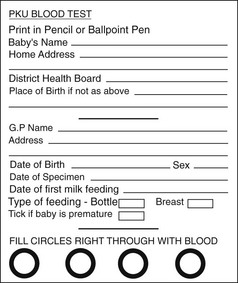

Many countries have screening programmes for diseases at birth. In the UK, newborns are screened for congenital hypothyroidism, phenylketonuria, cystic fibrosis, sickle-cell disease and medium-chain acyl CoA dehydrogenase deficiency. A blood sample is collected from every baby around the seventh day of life. Capillary blood sampling in the neonate is best performed on the plantar aspect of the foot, especially on the medial aspect of the posterior third, as shown in Figure 78.1. A ‘blood spot’ is collected on to a thick filter paper card (Fig 78.2). The specimen can be conveniently sent by mail to a central screening laboratory. The following questions are usually considered when discussing the cost-effectiveness of a screening programme.

Does the disease have a relatively high incidence?

Does the disease have a relatively high incidence?

Can the disease be detected within days of birth?

Can the disease be detected within days of birth?

Can the disease be identified by a biochemical marker which can be easily measured?

Can the disease be identified by a biochemical marker which can be easily measured?

Will the disease be missed clinically, and would this cause irreversible damage to the baby?

Will the disease be missed clinically, and would this cause irreversible damage to the baby?

Is the disease treatable, and will the result of the screening test be available before any irreversible damage to the baby has occurred?

Is the disease treatable, and will the result of the screening test be available before any irreversible damage to the baby has occurred?

Congenital hypothyroidism

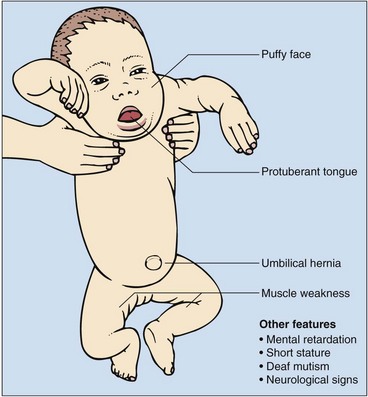

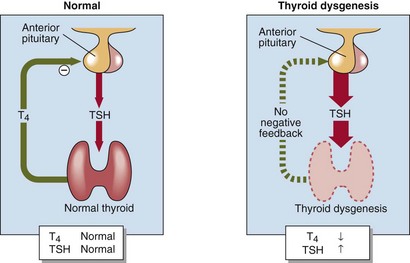

Primary hypothyroidism is present in one in every 4000 births in the UK. There is often no clinical evidence at birth that the baby is abnormal, yet if congenital hypothyroidism is unrecognized and untreated, affected children develop irreversible mental retardation and the characteristic features of cretinism (Fig 78.3). Most cases of congenital hypothyroidism are due to thyroid gland dysgenesis, the failure of the thyroid gland to develop properly during early embryonic growth. The presence of a high blood TSH concentration is the basis of the screening test (Fig 78.4). In addition to congenital hypothyroidism, iodine deficiency in the mother and/or the baby may also cause babies to be hypothyroid at birth, and to have a high TSH on screening. It is important that these babies are not incorrectly labelled as having congenital hypothyroidism and unnecessarily treated with thyroxine for life.

Phenylketonuria

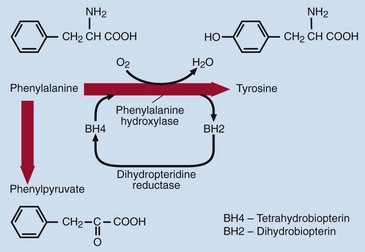

The incidence of phenylketonuria is around one in every 10 000 births in the UK. Phenylketonuria arises from impaired conversion of phenylalanine to tyrosine, usually because of a deficiency of phenylalanine hydroxylase. Figure 78.5 shows how phenylalanine, an essential amino acid, is metabolized. In phenylketonuria, phenylalanine cannot be converted to tyrosine, accumulates in blood and is excreted in the urine. The main urinary metabolite is phenylpyruvic acid (a ‘phenylketone’), which gives the disease its name. The clinical features include: